National Multi-Species Recovery Plan for the Carpentarian Antechinus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Felixer™ Grooming Trap Non-Target Safety Trial: Numbats July 2020

Felixer™ Grooming Trap Non-Target Safety Trial: Numbats July 2020 Brian Chambers, Judy Dunlop, Adrian Wayne Summary Felixer™ cat grooming traps are a novel and potential useful means for controlling feral cats that have proven difficult, or very expensive to control by other methods such as baiting, shooting and trapping. The South West Catchments Council (SWCC) and the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA) plan to undertake a meso-scale trial of Felixer™ traps in the southern jarrah forest where numbats (Myrmecobius fasciatus) are present. Felixer™ traps have not previously been deployed in areas with numbat populations. We tested the ability of Felixer™ traps to identify numbats as a non-target species by setting the traps in camera only mode in pens with four numbats at Perth Zoo. The Felixer™ traps were triggered 793 times by numbats with all detections classified as non-targets. We conclude that the Felixer™ trap presents no risk to numbats as a non-target species. Acknowledgements We are grateful Peter Mawson, Cathy Lambert, Karen Cavanough, Jessica Morrison and Aimee Moore of Perth Zoo for facilitating access to the numbats for the trial. The trial was approved by the Perth Zoo Animal Ethics Committee (Project No. 2020-4). The Felixer™ traps used in this project were provided by Fortescue Metals Group Pty Ltd and Roy Hill Mining Pty Ltd. This trial was supported by the South West Catchments Council with funding through the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. ii Felixer™ - Numbat Safety Trial -

Lindsay Masters

CHARACTERISATION OF EXPERIMENTALLY INDUCED AND SPONTANEOUSLY OCCURRING DISEASE WITHIN CAPTIVE BRED DASYURIDS Scott Andrew Lindsay A thesis submitted in fulfillment of requirements for the postgraduate degree of Masters of Veterinary Science Faculty of Veterinary Science University of Sydney March 2014 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY Apart from assistance acknowledged, this thesis represents the unaided work of the author. The text of this thesis contains no material previously published or written unless due reference to this material is made. This work has neither been presented nor is currently being presented for any other degree. Scott Lindsay 30 March 2014. i SUMMARY Neosporosis is a disease of worldwide distribution resulting from infection by the obligate intracellular apicomplexan protozoan parasite Neospora caninum, which is a major cause of infectious bovine abortion and a significant economic burden to the cattle industry. Definitive hosts are canid and an extensive range of identified susceptible intermediate hosts now includes native Australian species. Pilot experiments demonstrated the high disease susceptibility and the unexpected observation of rapid and prolific cyst formation in the fat-tailed dunnart (Sminthopsis crassicaudata) following inoculation with N. caninum. These findings contrast those in the immunocompetent rodent models and have enormous implications for the role of the dunnart as an animal model to study the molecular host-parasite interactions contributing to cyst formation. An immunohistochemical investigation of the dunnart host cellular response to inoculation with N. caninum was undertaken to determine if a detectable alteration contributes to cyst formation, compared with the eutherian models. Selective cell labelling was observed using novel antibodies developed against Tasmanian devil proteins (CD4, CD8, IgG and IgM) as well as appropriate labelling with additional antibodies targeting T cells (CD3), B cells (CD79b, PAX5), granulocytes, and the monocyte-macrophage family (MAC387). -

Kimberley Land Council Submission to the Australian Law Reform Commission Inquiry Into the Native Title Act: Issues Paper 45 General Comment

Kimberley Land Council Submission to the Australian Law Reform Commission Inquiry into the Native Title Act: Issues Paper 45 General comment The Kimberley Land Council (KLC) is the native title representative body for the Kimberley region of Western Australia. The KLC is also a grass roots community organisation which has represented the interests of Kimberley Traditional Owners in their struggle for recognition of ownership of country since 1978. The KLC is cognisant of the limitations of the Native Title Act (NTA) in addressing the wrongs of the past and providing a clear pathway to economic, social and cultural independence for Aboriginal people in the future. The KLC strongly supports the review of the NTA by the Australian Law Reform Commission (Review) in the hope that it might provide an increased capacity for the NTA to address both past wrongs and the future needs and aspirations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The dispossession of country which occurred as a result of colonisation has had a profound and long lasting impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Country (land and sea) is centrally important to the cultural, social and familial lives of Aboriginal people, and its dispossession has had profound and continuing intergenerational effects. However, interests in land (and waters) is also a primary economic asset and its dispossession from Traditional Owners has prevented them from enjoying the benefits of its utilisation for economic purposes, and bestowed those benefits on others (in particular, in the Kimberley, pastoral, mining and tourism interests). The role of the NTA is to provide one mechanism for the original dispossession of country to be addressed, albeit imperfectly and subject to competing interests. -

Platypus Collins, L.R

AUSTRALIAN MAMMALS BIOLOGY AND CAPTIVE MANAGEMENT Stephen Jackson © CSIRO 2003 All rights reserved. Except under the conditions described in the Australian Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, duplicating or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Contact CSIRO PUBLISHING for all permission requests. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Jackson, Stephen M. Australian mammals: Biology and captive management Bibliography. ISBN 0 643 06635 7. 1. Mammals – Australia. 2. Captive mammals. I. Title. 599.0994 Available from CSIRO PUBLISHING 150 Oxford Street (PO Box 1139) Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia Telephone: +61 3 9662 7666 Local call: 1300 788 000 (Australia only) Fax: +61 3 9662 7555 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.publish.csiro.au Cover photos courtesy Stephen Jackson, Esther Beaton and Nick Alexander Set in Minion and Optima Cover and text design by James Kelly Typeset by Desktop Concepts Pty Ltd Printed in Australia by Ligare REFERENCES reserved. Chapter 1 – Platypus Collins, L.R. (1973) Monotremes and Marsupials: A Reference for Zoological Institutions. Smithsonian Institution Press, rights Austin, M.A. (1997) A Practical Guide to the Successful Washington. All Handrearing of Tasmanian Marsupials. Regal Publications, Collins, G.H., Whittington, R.J. & Canfield, P.J. (1986) Melbourne. Theileria ornithorhynchi Mackerras, 1959 in the platypus, 2003. Beaven, M. (1997) Hand rearing of a juvenile platypus. Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Shaw). Journal of Wildlife Proceedings of the ASZK/ARAZPA Conference. 16–20 March. -

Northern Quoll ©

Species Fact Sheet: Northern quoll © V i e w f i n d e r Nothern quoll Dasyurus hallucatus The northern quoll is a medium-sized carnivorous marsupial that lives in the savannas of northern Australia. It is found from south-eastern Queensland all the way to the northern parts of the Western Australian coast. Populations have declined across much of this range, particularly as a result of the spread of the cane toad. Recent translocations to islands in northern Australia free from feral animals have had some success in increasing populations on islands Conservation status The World Conservation Union (IUCN) Redlist of Threatened Species: Lower risk – near threatened Australian Government - Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 : Endangered Did you know? Western Australia. They have been associated with the de - mise of a number of native species. • Although they are marsupials, female northern quolls do not have a pouch. At the start of the Conservation action breeding season the area around the nipples becomes enlarged and partially surrounded by a Communities, scientists and governments are working flap of skin. The young (usually six in a litter) live together to coordinate the research and management here for the first eight to 10 weeks of their lives. effort. The Threatened Species Network, a community- • Almost all male northern quolls die at about one based program of the Australian Government and WWF- year old, not long after mating. Australia, recently provided funding for Traditional Owners to survey Maria Island in the Northern Territory for northern Distribution and habitat quolls. On Groote Eylandt, the most significant island for northern quolls, a TSN Community Grant is providing funds Northern quolls live in a range of habitats but prefer rocky to help quarantine the island from hitch-hiking cane toads areas and eucalypt forests. -

A Phylogeny and Timescale for Marsupial Evolution Based on Sequences for Five Nuclear Genes

J Mammal Evol DOI 10.1007/s10914-007-9062-6 ORIGINAL PAPER A Phylogeny and Timescale for Marsupial Evolution Based on Sequences for Five Nuclear Genes Robert W. Meredith & Michael Westerman & Judd A. Case & Mark S. Springer # Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2007 Abstract Even though marsupials are taxonomically less diverse than placentals, they exhibit comparable morphological and ecological diversity. However, much of their fossil record is thought to be missing, particularly for the Australasian groups. The more than 330 living species of marsupials are grouped into three American (Didelphimorphia, Microbiotheria, and Paucituberculata) and four Australasian (Dasyuromorphia, Diprotodontia, Notoryctemorphia, and Peramelemorphia) orders. Interordinal relationships have been investigated using a wide range of methods that have often yielded contradictory results. Much of the controversy has focused on the placement of Dromiciops gliroides (Microbiotheria). Studies either support a sister-taxon relationship to a monophyletic Australasian clade or a nested position within the Australasian radiation. Familial relationships within the Diprotodontia have also proved difficult to resolve. Here, we examine higher-level marsupial relationships using a nuclear multigene molecular data set representing all living orders. Protein-coding portions of ApoB, BRCA1, IRBP, Rag1, and vWF were analyzed using maximum parsimony, maximum likelihood, and Bayesian methods. Two different Bayesian relaxed molecular clock methods were employed to construct a timescale for marsupial evolution and estimate the unrepresented basal branch length (UBBL). Maximum likelihood and Bayesian results suggest that the root of the marsupial tree is between Didelphimorphia and all other marsupials. All methods provide strong support for the monophyly of Australidelphia. Within Australidelphia, Dromiciops is the sister-taxon to a monophyletic Australasian clade. -

Management of the Terrestrial Small Mammal and Lizard Communities in the Dune System Of

Management of the terrestrial small mammal and lizard communities in the dune system of Sturt National Park, Australia: Historic and contemporary effects of pastoralism and fox predation Ulrike Sabine Klöcker (Dipl. – Biol., Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms Universität Bonn, Germany) Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences The University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia 2009 Abstract This thesis addressed three issues related to the management and conservation of small terrestrial vertebrates in the arid zone. The study site was an amalgamation of pastoral properties forming the now protected area of Sturt National Park in far-western New South Wales, Australia. Thus firstly, it assessed recovery from disturbance accrued through more than a century of Sheep grazing. Vegetation parameters, Fox, Cat and Rabbit abundance, and the small vertebrate communities were compared, with distance to watering points used as a surrogate for grazing intensity. Secondly, the impacts of small-scale but intensive combined Fox and Rabbit control on small vertebrates were investigated. Thirdly, the ecology of the rare Dusky Hopping Mouse (Notomys fuscus) was used as an exemplar to illustrate and discuss some of the complexities related to the conservation of small terrestrial vertebrates, with a particular focus on desert rodents. Thirty-five years after the removal of livestock and the closure of watering points, areas that were historically heavily disturbed are now nearly indistinguishable from nearby relatively undisturbed areas, despite uncontrolled native herbivore (kangaroo) abundance. Rainfall patterns, rather than grazing history, were responsible for the observed variation between individual sites and may overlay potential residual grazing effects. -

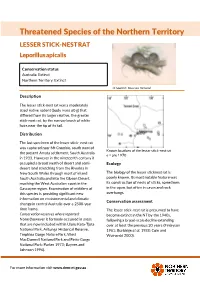

LESSER STICK-NEST RAT Leporillus Apicalis

Threatened Species of the Northern Territory LESSER STICK-NEST RAT Leporillus apicalis Conservation status Australia: Extinct Northern Territory: Extinct (J Gould © Museum Victoria) Description The lesser stick-nest rat was a moderately sized native rodent (body mass 60 g) that differed from its larger relative, the greater stick-nest rat, by the narrow brush of white hairs near the tip of its tail. Distribution The last specimen of the lesser stick- nest rat was captured near Mt Crombie, south west of Known locations of the lesser stick-nest rat the present Amata settlement, South Australia ο = pre 1970 in 1933. However in the nineteenth century it occupied a broad swath of desert and semi- Ecology desert land stretching from the Riverina in New South Wales through most of inland The biology of the lesser sticknest rat is South Australia and into the Gibson Desert, poorly known. Its most notable feature was reaching the West Australian coast in the its construction of nests of sticks, sometimes Gascoyne region. Examination of middens of in the open, but often in caves and rock this species is providing significant new overhangs. information on environmental and climatic Conservation assessment change in central Australia over a 2500-year time frame. The lesser stick-nest rat is presumed to have Conservation reserves where reported: become extinct in the NT by the 1940s, None (however it formerly occurred in areas following a broad-scale decline extending that are now included within Uluru Kata-Tjuta over at least the previous 30 years (Finlayson National Park, Arltunga Historical Reserve, 1961; Burbidge et al. -

Impact of Fox Baiting on Tiger Quoll Populations Project ID: 00016505

Impact of fox baiting on tiger quoll populations Project ID: 00016505 Final Report to Environment Australia and The New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service Gerhard Körtner and Shaan Gresser Copyright G. Körtner Executive Summary: The NSW Threat Abatement Plan for Predation by the Red Fox (TAP) identifies foxes as a major threat to the survival of many native mammals. The plan recommends baiting with compound 1080 (sodium monofluoroacetate) because it appears to be the most effective fox control measure. However, the plan also recognises the risk for tiger quolls as a non-target species. Although the actual impact of 1080 fox baiting on tiger quoll populations has not been assessed, this assumed risk has resulted in restrictions on the use of 1080 which render fox baiting programs labour intensive and expensive and which may compromise the effectiveness of the fox control. The aim of this project is to determine whether these precautions are necessary by measuring tiger quoll mortality during fox baiting programs using 1080. The project has been identified as a priority action (Obj. 2, action 5) of the TAP. Three experiments were conducted in north-east NSW between June 2000 and December 2001. Overall 78 quolls were trapped and 56 of those were fitted with mortality radio-transmitters. Baiting procedure followed Best Practice Guidelines (TAP) except that there was no free-feeding and baits were only surface buried. These modifications aimed to increase the exposure of quolls to bait. 1080 baits (3 mg / bait; Foxoff®) incorporating the bait marker Rhodamine B were deployed for 10 days along existing trails. -

Ba3444 MAMMAL BOOKLET FINAL.Indd

Intot Obliv i The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia Compiled by James Fitzsimons Sarah Legge Barry Traill John Woinarski Into Oblivion? The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia 1 SUMMARY Since European settlement, the deepest loss of Australian biodiversity has been the spate of extinctions of endemic mammals. Historically, these losses occurred mostly in inland and in temperate parts of the country, and largely between 1890 and 1950. A new wave of extinctions is now threatening Australian mammals, this time in northern Australia. Many mammal species are in sharp decline across the north, even in extensive natural areas managed primarily for conservation. The main evidence of this decline comes consistently from two contrasting sources: robust scientifi c monitoring programs and more broad-scale Indigenous knowledge. The main drivers of the mammal decline in northern Australia include inappropriate fi re regimes (too much fi re) and predation by feral cats. Cane Toads are also implicated, particularly to the recent catastrophic decline of the Northern Quoll. Furthermore, some impacts are due to vegetation changes associated with the pastoral industry. Disease could also be a factor, but to date there is little evidence for or against it. Based on current trends, many native mammals will become extinct in northern Australia in the next 10-20 years, and even the largest and most iconic national parks in northern Australia will lose native mammal species. This problem needs to be solved. The fi rst step towards a solution is to recognise the problem, and this publication seeks to alert the Australian community and decision makers to this urgent issue. -

Karajarri Literature Review 2014

Tukujana Nganyjurrukura Ngurra All of us looking after country together Literature Review for Terrestrial & Marine Environments on Karajarri Land and Sea Country Compiled by Tim Willing 2014 Acknowledgements The following individuals are thanked for assistance in the DISCLAIMERS compilation of this report: The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the Karajarri Rangers and Co-ordinator Thomas King; author and do not necessarily reflect the official view of the Kimberley Land Council’s Land and Sea Management unit. While reasonable Members of the Karajarri Traditional Lands Association efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication (KTLA) and IPA Cultural Advisory Committee: Joseph Edgar, are factually correct, the Land and Sea Management Unit accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents. To the Mervyn Mulardy Jnr, Joe Munro, Geraldine George, Jaqueline extent permitted by law, the Kimberley Land Council excludes all liability Shovellor, Anna Dwyer, Alma Bin Rashid, Faye Dean, Frankie to any person for any consequences, including, but not limited to all Shovellor, Lenny Hopiga, Shirley Spratt, Sylvia Shovellor, losses, damages, costs, expenses, and any other compensation, arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in part or in whole) and Celia Bennett, Wittidong Mulardy, Jessica Bangu and Rosie any information or material contained in it. Munro. This report contains cultural and intellectual property belonging to the Richard Meister from the KLC Land and Sea Management Karajarri Traditional Lands Association. Users are accordingly cautioned Unit, for coordination, meeting and editorial support as well to seek formal permission before reproducing any material from this report. -

Spotted Tailed Quoll (Dasyurus Maculatus)

Husbandry Guidelines for the SPOTTED-TAILED QUOLL (Tiger Quoll) (Photo: J. Marten) Dasyurus maculatus (MAMMALIA: DASYURIDAE) Author: Julie Marten Date of Preparation: February 2013 – June 2014 Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond Course Name and Number: Captive Animals Certificate III (18913) Lecturers: Graeme Phipps, Jacki Salkeld, Brad Walker DISCLAIMER Please note that this information is just a guide. It is not a definitive set of rules on how the care of Spotted- Tailed Quolls must be conducted. Information provided may vary for: • Individual Spotted-Tailed Quolls • Spotted-Tailed Quolls from different regions of Australia • Spotted-Tailed Quolls kept in zoos versus Spotted-Tailed Quolls from the wild • Spotted-Tailed Quolls kept in different zoos Additionally different zoos have their own set of rules and guidelines on how to provide husbandry for their Spotted-Tailed Quolls. Even though I researched from many sources and consulted various people, there are zoos and individual keepers, researchers etc. that have more knowledge than myself and additional research should always be conducted before partaking any new activity. Legislations are regularly changing and therefore it is recommended to research policies set out by national and state government and associations such as ARAZPA, ZAA etc. Any incident resulting from the misuse of this document will not be recognised as the responsibility of the author. Please use at the participants discretion. Any enhancements to this document to increase animal care standards and husbandry techniques are appreciated. Otherwise I hope this manual provides some helpful information. Julie Marten Picture J.Marten 2 OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY RISKS It is important before conducting any work that all hazards are identified.