Rock Glaciers on James Ross Island, Antarctica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

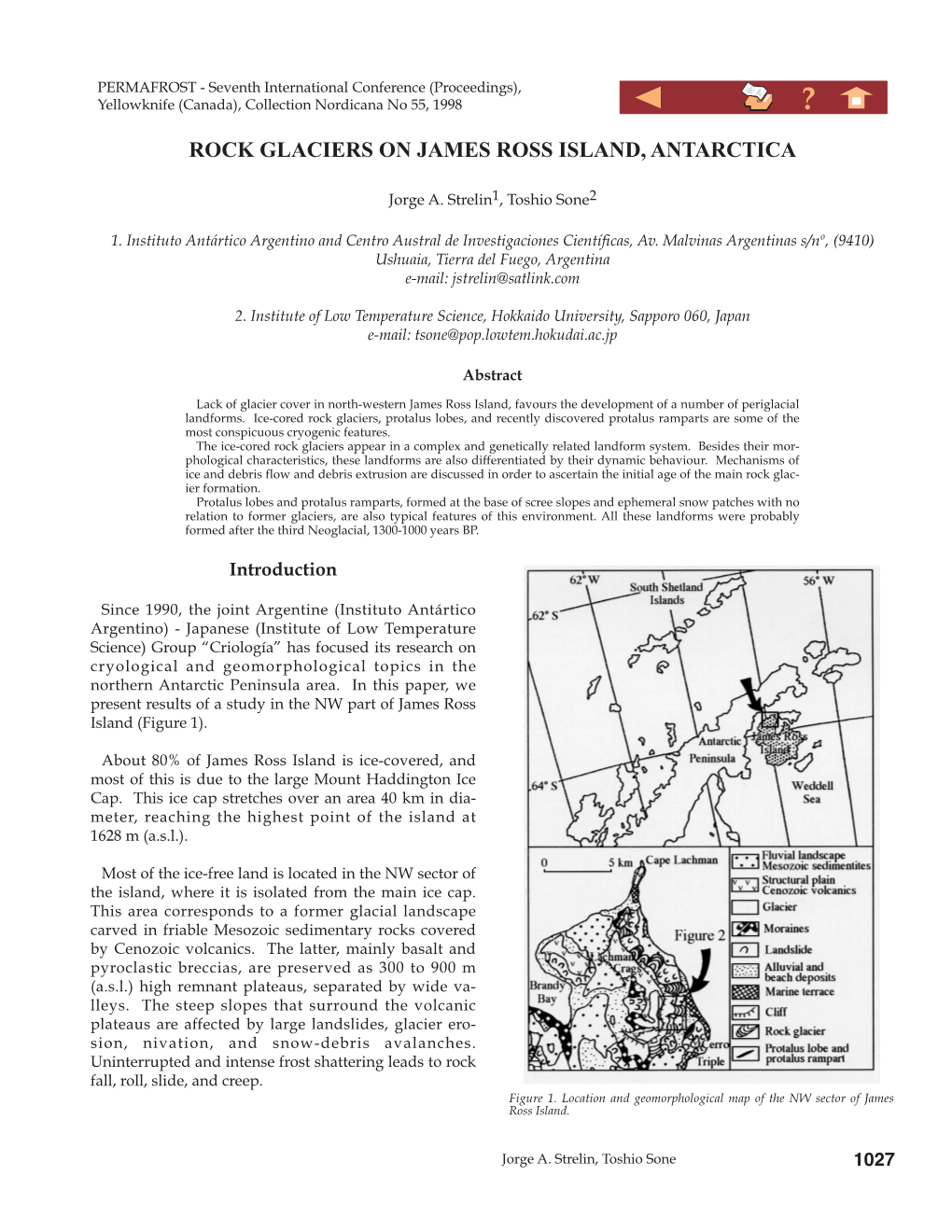

Recommended publications

-

High-Mountain Permafrost in the Austrian Alps (Europe)

HIGH-MOUNTAIN PERMAFROST IN THE AUSTRIAN ALPS (EUROPE) Gerhard Karl Lieb Institute of Geography University of Graz Heinrichstrasse 36 A-8010 Graz e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Permafrost research in the Austrian Alps (Eastern Alps) is based on a variety of methods, including at large scales, the measurement of the temperature of springs and of the base of winter snow cover, and at small scales, mainly an inventory of some 1450 rock glaciers. Taking all the information available into consideration, the lower limit of discontinuous permafrost is situated near 2500 m in most of the Austrian Alps. These results can be used for modelling the permafrost distribution within a geographical information system. Detailed investi- gations were carried out in the Doesen Valley (Hohe Tauern range) using additional methods, including several geophysical soundings. In this way, realistic estimates of certain permafrost characteristics and the volume of a large active rock glacier (some 15x106m3) were possible. This rock glacier has been chosen as a monitoring site to observe the effects of past and future climatic change. Introduction snow cover (BTS) and geophysical soundings, such as seismic, geoelectric, electromagnetic and ground pene- Although mountain permafrost in the Austrian Alps trating radar surveys have been published (survey and has caused construction problems and damage to buil- references in Lieb, 1996). The best results for mapping dings at several high-altitude locations, specific investi- the mere existence of permafrost were obtained by mea- gations of permafrost did not start until 1980. Since suring spring temperatures and BTS, both procedures then, studies of the distribution and certain characteris- being easily applicable and providing quite accurate tics of permafrost have been carried out at a number of interpretation. -

Late Wisconsin Climate Inferences from Rock Glaciers in South-Central

LateWisconsin climatic inlerences from rock glaciers in south-centraland west-central New Mexico andeast-central Arizona byJohn W. Blagbrough, P0 Box8063, Albuquerque, NewMexico 87198 Abstract Inactive rock glaciersof late Wisconsin age occur at seven sites in south-central and west-central New Mexico and in east-centralArizona. They are at the base of steep talus in the heads of canyons and ravines and have surfacefeatures indicating they are ice-cemented (permafrost) forms that moved by the flow of interstitial ice. The rock glaciersindicate zones of alpine permafrost with lower levels that rise from approximately 2,400m in the east region to 2,950 m in the west. Within the zones the mean annual temperaturewas below freezing, and the climatewas marked by much diurnal freezing and thawing resulting in the production of large volumes of talus in favorableterrain. The snow cover was thin and of short duration, which fa- vored ground freezing and cryofraction. The rock glaciers in the east region occur near the late Wisconsin 0'C air isotherm and implv that the mean annual temperature was depressedapproximately 7 to 8'C during a periglacial episodein the late Wisconsin.A dry continental climate with a seasonaldistribution of precipitation similar to that of the present probably prevailed, and timberline former timberlines. may have been depresseda minimum of 1,240m. The rise in elevation of the rock glaciersfrom east to west acrossthe region is attributed to greater snowfall in west-centralNew Mexico and east-centralArizona, which reducedthe inten- sity and depth of ground freezing near the late Wisconsin 0"C air isotherm. -

Cold-Climate Landform Patterns in the Sudetes. Effects of Lithology, Relief and Glacial History

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS CAROLINAE 2000 GEOGRAPHICA, XXXV, SUPPLEMENTUM, PAG. 185–210 Cold-climate landform patterns in the Sudetes. Effects of lithology, relief and glacial history ANDRZEJ TRACZYK, PIOTR MIGOŃ University of Wrocław, Department of Geography, Wrocław, Poland ABSTRACT The Sudetes have the whole range of landforms and deposits, traditionally described as periglacial. These include blockfields and blockslopes, frost-riven cliffs, tors and cryoplanation terraces, solifluction mantles, rock glaciers, talus slopes and patterned ground and loess covers. This paper examines the influence, which lithology and structure, inherited relief and time may have had on their development. It appears that different rock types support different associations of cold climate landforms. Rock glaciers, blockfields and blockstreams develop on massive, well-jointed rocks. Cryogenic terraces, rock steps, patterned ground and heterogenic solifluction mantles are typical for most metamorphic rocks. No distinctive landforms occur on rocks breaking down through microgelivation. The variety of slope form is largely inherited from pre- Pleistocene times and includes convex-concave, stepped, pediment-like, gravitational rectilinear and concave free face-talus slopes. In spite of ubiquitous solifluction and permafrost creep no uniform characteristic ‘periglacial’ slope profile has been created. Mid-Pleistocene trimline has been identified on nunataks in the formerly glaciated part of the Sudetes and in their foreland. Hence it is proposed that rock-cut periglacial relief of the Sudetes is the cumulative effect of many successive cold periods during the Pleistocene and the last glacial period alone was of relatively minor importance. By contrast, slope cover deposits are usually of the Last Glacial age. Key words: cold-climate landforms, the Sudetes 1. -

a Pleistocene Ice Sheet in the .' Northern Boulder Mountains

, A Pleistocene Ice Sheet in the .' Northern Boulder Mountains .< Jefferson, Powell, and Lewis and Clark Counties, Montana By EDWARD T. RUPPEL CONTRIBUTIONS TO GENERAL GEOLOGY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1141-G A descriptive report of the glacial geology in the northern part of the Boulder Mountains, Montana UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1962 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.C. CONTENTS Page Abstract- _______-_-______-__-_--____--___________--____-_-_-______ G-1 Introduction. _ _____________________________________________________ 1 Summary of bedrock geology.___-___-____.____._-___._.__--__--_.___ 4 Surficial geology.._________________________________________________ 5 Northern Boulder Mountains ice sheet- ___-____-___.----_-_--_-__ 5 Glacial erosion.___________________________________________ 7 Glacial deposits.-______--_^______-________________________ 9 Age and regional relations of glaciation.___:______.____________ 11 Postglacial erosion.---___-_--________-___---___-_-------__---__ 13 Creep-and-solifluction deposits and stone-banked terrace deposits. 14 Frost-wedged rock waste and boulders of disintegration........ 15 Landslides._______________________________________________ 19 Bog and swamp deposits. _______________________________"___ 20 Age of mass-wasting deposits--....----...--___---__---_--_. 20 References cited..____________________________ _____________________ 21 ILLUSTRATIONS [Plates in pocket] PLATE 1. Ice coverage and flow, Basin quadrangle, Jefferson, Lewis and Clark, and Powell Counties, Mont. 2. Interpretations of Pleistocene and Recent history, Montana and adjacent areas. FIGURE 1. Inferred limits of northern Boulder Mountains ice sheet, G-2 2. Typical rounded topography along Continental Divide in northern part of Boulder Mountains---.-,-.------ ------- 3 3. -

Chapter 7 Seasonal Snow Cover, Ice and Permafrost

I Chapter 7 Seasonal snow cover, ice and permafrost Co-Chairmen: R.B. Street, Canada P.I. Melnikov, USSR Expert contributors: D. Riseborough (Canada); O. Anisimov (USSR); Cheng Guodong (China); V.J. Lunardini (USA); M. Gavrilova (USSR); E.A. Köster (The Netherlands); R.M. Koerner (Canada); M.F. Meier (USA); M. Smith (Canada); H. Baker (Canada); N.A. Grave (USSR); CM. Clapperton (UK); M. Brugman (Canada); S.M. Hodge (USA); L. Menchaca (Mexico); A.S. Judge (Canada); P.G. Quilty (Australia); R.Hansson (Norway); J.A. Heginbottom (Canada); H. Keys (New Zealand); D.A. Etkin (Canada); F.E. Nelson (USA); D.M. Barnett (Canada); B. Fitzharris (New Zealand); I.M. Whillans (USA); A.A. Velichko (USSR); R. Haugen (USA); F. Sayles (USA); Contents 1 Introduction 7-1 2 Environmental impacts 7-2 2.1 Seasonal snow cover 7-2 2.2 Ice sheets and glaciers 7-4 2.3 Permafrost 7-7 2.3.1 Nature, extent and stability of permafrost 7-7 2.3.2 Responses of permafrost to climatic changes 7-10 2.3.2.1 Changes in permafrost distribution 7-12 2.3.2.2 Implications of permafrost degradation 7-14 2.3.3 Gas hydrates and methane 7-15 2.4 Seasonally frozen ground 7-16 3 Socioeconomic consequences 7-16 3.1 Seasonal snow cover 7-16 3.2 Glaciers and ice sheets 7-17 3.3 Permafrost 7-18 3.4 Seasonally frozen ground 7-22 4 Future deliberations 7-22 Tables Table 7.1 Relative extent of terrestrial areas of seasonal snow cover, ice and permafrost (after Washburn, 1980a and Rott, 1983) 7-2 Table 7.2 Characteristics of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets (based on Oerlemans and van der Veen, 1984) 7-5 Table 7.3 Effect of terrestrial ice sheets on sea-level, adapted from Workshop on Glaciers, Ice Sheets and Sea Level: Effect of a COylnduced Climatic Change. -

Periglacial Processes, Features & Landscape Development 3.1.4.3/4

Periglacial processes, features & landscape development 3.1.4.3/4 Glacial Systems and landscapes What you need to know Where periglacial landscapes are found and what their key characteristics are The range of processes operating in a periglacial landscape How a range of periglacial landforms develop and what their characteristics are The relationship between process, time, landforms and landscapes in periglacial settings Introduction A periglacial environment used to refer to places which were near to or at the edge of ice sheets and glaciers. However, this has now been changed and refers to areas with permafrost that also experience a seasonal change in temperature, occasionally rising above 0 degrees Celsius. But they are characterised by permanently low temperatures. Location of periglacial areas Due to periglacial environments now referring to places with permafrost as well as edges of glaciers, this can account for one third of the Earth’s surface. Far northern and southern hemisphere regions are classed as containing periglacial areas, particularly in the countries of Canada, USA (Alaska) and Russia. Permafrost is where the soil, rock and moisture content below the surface remains permanently frozen throughout the entire year. It can be subdivided into the following: • Continuous (unbroken stretches of permafrost) • extensive discontinuous (predominantly permafrost with localised melts) • sporadic discontinuous (largely thawed ground with permafrost zones) • isolated (discrete pockets of permafrost) • subsea (permafrost occupying sea bed) Whilst permafrost is not needed in the development of all periglacial landforms, most periglacial regions have permafrost beneath them and it can influence the processes that create the landforms. Many locations within SAMPLEextensive discontinuous and sporadic discontinuous permafrost will thaw in the summer months. -

Permafrost Soils and Carbon Cycling

SOIL, 1, 147–171, 2015 www.soil-journal.net/1/147/2015/ doi:10.5194/soil-1-147-2015 SOIL © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Permafrost soils and carbon cycling C. L. Ping1, J. D. Jastrow2, M. T. Jorgenson3, G. J. Michaelson1, and Y. L. Shur4 1Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station, Palmer Research Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 1509 South Georgeson Road, Palmer, AK 99645, USA 2Biosciences Division, Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL 60439, USA 3Alaska Ecoscience, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA 4Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA Correspondence to: C. L. Ping ([email protected]) Received: 4 October 2014 – Published in SOIL Discuss.: 30 October 2014 Revised: – – Accepted: 24 December 2014 – Published: 5 February 2015 Abstract. Knowledge of soils in the permafrost region has advanced immensely in recent decades, despite the remoteness and inaccessibility of most of the region and the sampling limitations posed by the severe environ- ment. These efforts significantly increased estimates of the amount of organic carbon stored in permafrost-region soils and improved understanding of how pedogenic processes unique to permafrost environments built enor- mous organic carbon stocks during the Quaternary. This knowledge has also called attention to the importance of permafrost-affected soils to the global carbon cycle and the potential vulnerability of the region’s soil or- ganic carbon (SOC) stocks to changing climatic conditions. In this review, we briefly introduce the permafrost characteristics, ice structures, and cryopedogenic processes that shape the development of permafrost-affected soils, and discuss their effects on soil structures and on organic matter distributions within the soil profile. -

Frozen Ground

Frozen Ground Th e News Bulletin of the International Permafrost Association Number 32, December 2008 INTERNATIONAL PERMAFROST ASSOCIATION Th e International Permafrost Association, founded in 1983, has as its objectives to foster the dissemination of knowledge concerning permafrost and to promote cooperation among persons and national or international organisations engaged in scientifi c investigation and engineering work on permafrost. Membership is through national Adhering Bodies and Associate Members. Th e IPA is governed by its offi cers and a Council consisting of representatives from 26 Adhering Bodies having interests in some aspect of theoretical, basic and applied frozen ground research, including permafrost, seasonal frost, artifi cial freezing and periglacial phenomena. Committees, Working Groups, and Task Forces organise and coordinate research activities and special projects. Th e IPA became an Affi liated Organisation of the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) in July 1989. Beginning in 1995 the IPA and the International Geographical Union (IGU) developed an Agreement of Cooperation, thus making IPA an affi liate of the IGU. Th e Association’s primary responsibilities are convening International Permafrost Conferences, undertaking special projects such as preparing databases, maps, bibliographies, and glossaries, and coordinating international fi eld programmes and networks. Conferences were held in West Lafayette, Indiana, U.S.A., 1963; in Yakutsk, Siberia, 1973; in Edmonton, Canada, 1978; in Fairbanks, Alaska, 1983; in Trondheim, Norway, 1988; in Beijing, China, 1993; in Yellowknife, Canada, 1998, in Zurich, Switzerland, 2003, and in Fairbanks, Alaska, in 2008. Th e Tenth conference will be in Tyumen, Russia, in 2012.Field excursions are an integral part of each Conference, and are organised by the host Executive Committee 2008-2012 Council Members Professor Hans-W. -

Inventory and Distribution of Rock Glaciers in Northeastern Yakutia

land Article Inventory and Distribution of Rock Glaciers in Northeastern Yakutia Vasylii Lytkin Melnikov Permafrost Institute, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Yakutsk 677010, Russia; [email protected] Received: 2 September 2020; Accepted: 8 October 2020; Published: 10 October 2020 Abstract: Rock glaciers are common forms of relief of the periglacial belt of many mountain structures in the world. They are potential sources of water in arid and semi-arid regions, and therefore their analysis is important in assessing water reserves. Mountain structures in the north-east of Yakutia have optimal conditions for the formation of rock glaciers, but they have not yet been studied in this regard. In this article, for the first time, we present a detailed list of rock glaciers in this region. Based on geoinformation mapping using remote sensing data and field studies within the Chersky, Verkhoyansk, Momsky and Suntar-Khayata ranges, 4503 rock glaciers with a total area of 224.6 km2 were discovered. They are located within absolute altitudes, from 503 to 2496 m. Their average minimum altitude was at 1456 m above sea level, and the maximum at 1527 m. Most of these formations are located on the sides of the trough valleys, and form extended sloping types of rock glaciers. An assessment of the exposure of the slopes where the rock glaciers are located showed that most of the rock glaciers are facing north and south. Keywords: rock glacier; permafrost; inventory; northeastern Yakutia; remote sensing 1. Introduction The geography of distribution of rock glaciers is quite extensive. They are found in many mountainous regions of Europe, North and South America and Asia, including some circumpolar regions [1–18]. -

Reidentifying Depositional, Solifluction, “String Lobe” Landforms As Erosional, Topographic, Steps & Risers Formed by Paleo-Snowdunes in Pennsylvania, USA

Earth Sciences 2021; 10(3): 136-144 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/earth doi: 10.11648/j.earth.20211003.19 ISSN: 2328-5974 (Print); ISSN: 2328-5982 (Online) Reidentifying Depositional, Solifluction, “String Lobe” Landforms as Erosional, Topographic, Steps & Risers Formed by Paleo-Snowdunes in Pennsylvania, USA Michael Iannicelli Brooklyn College (C. U. N. Y.), Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Brooklyn, N. Y., USA Email address: To cite this article: Michael Iannicelli. Reidentifying Depositional, Solifluction, “String Lobe” Landforms as Erosional, Topographic, Steps & Risers Formed by Paleo-Snowdunes in Pennsylvania, USA. Earth Sciences. Vol. 10, No. 3, 2021, pp. 136-144. doi: 10.11648/j.earth.20211003.19 Received: May 13, 2021; Accepted: June 9, 2021; Published: June 30, 2021 Abstract: A controversy arises concerning relict, ubiquitous, depositional, solifluction, “string lobe” landforms in the Ridge and Valley province of Pennsylvania, reported by other investigators. A distinguishment is made here by defending an original interpretation of the particular landforms which identified these as snowdune meltwater-eroded depressions formed within colluvium during cold phases of the Pleistocene Epoch. Hence, the landforms are reassessed as “steps & risers” in this study which is jargon associated with nival erosion. The reidentification is warranted in the study because of multiple lines of evidence including: the landforms’ detailed geomorphology and sedimentology; the landforms having a highly, unusual, very repetitive, NE-SW orientation; and the landforms incurring a striking, gravity-defying, characteristic of running-water erosion repeatedly occurring irrespective of the steepest part of the general slope. Besides the evidence offered here, the study also gives insight, resolutions and re-confirmations in order to establish absolute identification while differentiating between discussed, periglacial, relict landforms. -

Tundra Polygons. Photographic Interpretation and Field Studies in North-Norwegian Polygon Areas

Tundra polygons. Photographic interpretation and field studies in North-Norwegian polygon areas. By Harald Svensson Introduction. When working with aerial photos, the interpreter very soon realizes that the vegetation adjusts itself very well to differences in the ground conditions, which is in this way registered in photography. This fact constituted one of the starting points when the author, with the help of aerial photos, began the search for large-scale patterned ground of the tundra polygon shape, which earlier had not been identified in Scandinavia.1 In Arctic regions, recent tundra polygons can be clearly distinguished on aerial photographs which is a well-known fact derived from numerous investigations (amongst others, Troll 1944, Washburn 1950, Black 1952, Andreev 1955, Hopkins, Karlstrom et al 1955). The fact that there are considerable changes in the soil caused by the frost (cf. Figs. 1, 2 and 3) supports the hypothesis that, if a polygonal pattern of the tundra type developed in an area and this, at a later date in a milder climate, came to lic outside the tundra zone, it should be possible to trace fossil polygons or fragments of such with the help of the adjustment of the vegetation to the ground conditions. This idea has been followed up in order to in vestigate the correctness of the hypothesis and in order to check the possibility of this method. 1) In vertical sections and gravel-pits, however, fossil periglacial formations have been observed and studied particularly in Denmark and Southern Sweden (Norvang and Johnsson). As regards Swedish investigations of patterned ground reference is made to the surveys by Rapp and Rudberg (1960) and J. -

Glossary of Landscape and Vegetation Ecology for Alaska

U. S. Department of the Interior BLM-Alaska Technical Report to Bureau of Land Management BLM/AK/TR-84/1 O December' 1984 reprinted October.·2001 Alaska State Office 222 West 7th Avenue, #13 Anchorage, Alaska 99513 Glossary of Landscape and Vegetation Ecology for Alaska Herman W. Gabriel and Stephen S. Talbot The Authors HERMAN w. GABRIEL is an ecologist with the USDI Bureau of Land Management, Alaska State Office in Anchorage, Alaskao He holds a B.S. degree from Virginia Polytechnic Institute and a Ph.D from the University of Montanao From 1956 to 1961 he was a forest inventory specialist with the USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Regiono In 1966-67 he served as an inventory expert with UN-FAO in Ecuador. Dra Gabriel moved to Alaska in 1971 where his interest in the description and classification of vegetation has continued. STEPHEN Sa TALBOT was, when work began on this glossary, an ecologist with the USDI Bureau of Land Management, Alaska State Office. He holds a B.A. degree from Bates College, an M.Ao from the University of Massachusetts, and a Ph.D from the University of Alberta. His experience with northern vegetation includes three years as a research scientist with the Canadian Forestry Service in the Northwest Territories before moving to Alaska in 1978 as a botanist with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. or. Talbot is now a general biologist with the USDI Fish and Wildlife Service, Refuge Division, Anchorage, where he is conducting baseline studies of the vegetation of national wildlife refuges. ' . Glossary of Landscape and Vegetation Ecology for Alaska Herman W.