a Pleistocene Ice Sheet in the .' Northern Boulder Mountains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impacts of Sedimentation and Drivers of Variability in the Boulder Patch

Environmental Studies Program: Ongoing Study Title Impacts of Sedimentation and Drivers of Variability in the Boulder Patch Community, Beaufort Sea (AK-19-01) Administered by Anchorage, Alaska Office BOEM Contact(s) Rick Raymond [email protected] Conducting Organizations(s) University of Texas at Austin and UAF Total BOEM Cost $750,000 Performance Period FY 2019–2024 Final Report Due June 2024 Date Revised October 4, 2019 PICOC Summary Problem The Boulder Patch provides complex and unique habitat and supports high biodiversity in an area of considerable oil and gas interest, which includes the proposed construction of Liberty Island (less than half a mile away). Impacts of industry activity may smother/bury/kill productive biological area, but mitigation measures may be possible. Intervention This study will conduct a monitoring program to examine long-term drivers of community variability during Liberty development activities. In addition, it will test possible mitigation measures using common industry materials to “reseed” or replace habitat lost due to Liberty Island development activities. Comparison The post-development community structure will be compared against historic data to assess impacts of O&G activity. Further, artificial substrate will be compared to buried boulders to test efficacy of using industry materials to mitigate development impacts. Outcome Results will include defined spatial gradients and temporal trends in environmental conditions, benthic community structure, and kelp production in the Boulder Patch community; evaluation of the effect of sediments on Boulder Patch community; and assessment of test artificial substrates as possible habitat mitigation. Context Impacts of Sedimentation and Drivers of Variability in the Boulder Patch Community, Beaufort Sea (AK-19-01) BOEM Information Need(s): Impacts to the Boulder Patch from proposed gravel island construction were identified by local communities as a concern during scoping for Liberty Island. -

Influence of Boulder Concentration on Turbulence and Sediment

PUBLICATIONS Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface RESEARCH ARTICLE Influence of Boulder Concentration on Turbulence 10.1002/2017JF004221 and Sediment Transport in Open-Channel Flow Key Points: Over Submerged Boulders • The presence of large immobile boulders significantly influences the H. W. Fang1, Y. Liu1, and T. Stoesser2 flow and turbulence field in the vicinity of submerged boulders 1Department of Hydraulic Engineering, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2School of Civil Engineering, Cardiff University, • The boulder concentration plays an important role in forming skimming to Cardiff, UK isolated roughness flows and predicting bed load transport rates • The bed load transport rate will be Abstract In this paper the effects of boulder concentration on hydrodynamics and local and underestimated when using the reach-averaged sediment transport properties with a flow over submerged boulder arrays are investigated. reach-averaged shear stress, ’ compared with that based on local Four numerical simulations are performed in which the boulders streamwise spacings are varied. Statistics shear stress of near-bed velocity, Reynolds shear stresses, and turbulent events are collected and used to predict bed load transport rates. The results demonstrate that the presence of boulders at various interboulder spacings fl fi fl Supporting Information: altered the ow eld in their vicinity causing (1) ow deceleration, wake formation, and vortex shedding; • Supporting Information S1 (2) enhanced outward and inward interaction turbulence events downstream of the boulders; and (3) a • Movie S1 redistribution of the local bed shear stress around the boulder consisting of pockets of high and low bed shear stresses. The spatial variety of the predicted bed load transport rate qs based on local bed shear stress is Correspondence to: Y. -

2016 Longshore Size Grading on a Boulder Beach

LONGSHORE SIZE GRADING ON A BOULDER BEACH ANDREW GREEN, ANDREW COOPER, AND LESLEE SALZMANN ABSTRACT Longshore size sorting on boulder beaches has not previously been reported. In a boulder beach comprising beachrock slabs, we report systematic longshore clast size grading. The boulder beach at Mission Rocks, South Africa is deposited on an elevated (þ3 m MSL) shore platform and comprises imbricated clasts up to 5 m in the a-axis dimension (9 tonnes). The clasts are derived from adjacent intertidal beachrock and eolianite outcrops and are emplaced during high-magnitude wave events. Four distinct downdrift-fining cells are present. Each is 40–50 m long. The sorting is attributed to post-emplacement clast redistribution in which the smallest clasts are transported most frequently (by lower-magnitude storms) and therefore travel farthest downdrift. The updrift cell boundary is marked by boulders (5 m in length) that exceed the transport threshold for all but the most energetic of storms while the downdrift limit contains clasts 0.3 m in length. This mechanism of longshore size sorting does not rely on variations in longshore wave power as does cell development on sand and gravel beaches. The alongshore sorting via multiple high- (and variable-) magnitude events over a period of time, distinguishes these coarse clast deposits from those of single extreme events (whether storms or tsunamis). INTRODUCTION The longshore sorting of beach sediment by waves has received much attention. On sand and gravel beaches longshore sorting is manifest in variability of size (Komar 1977; Stapor and May 1983) and shape (Bluck 1967; Carr 1969; Carr 1971; Illenberger 1991) and may also be reflected in heavy- mineral distributions (Frihy and Komar 1991; Li and Komar 1992; Frihy and Lotfy 1997). -

1 El Niño and Intertidal Boulder Field Sedimentation at Point Reyes

Blair Conklin El Niño Sedimentation Spring 2017 El Niño and intertidal boulder field sedimentation at Point Reyes National Seashore Blair Conklin ABSTRACT Wave-exposed boulder fields, a common feature of the California coast, encounter drastic fluctuations in the amount of sand within them. This study examined the inter-annual and seasonal differences of sedimentation in an intertidal boulder field from September 2014 to March 2017. The study period included one El Niño winter, characterized by increased wave energy, and two ENSO-neutral winters. I used monthly photographs to qualitatively monitor sedimentation at two intertidal boulder fields in northern California. Sand depth was also measured within the boulder fields, and those measurements were positively correlated to the photographic assessments of sedimentation. Only one of the sites exhibited a strong seasonal cycle in sedimentation. Additionally, there were no differences in sedimentation between El Niño and ENSO-neutral winters. The results of this study indicate that sedimentation and erosion on beaches can vary dramatically between adjacent shorelines based on physical factors, such as exposure to swell conditions. Monitoring and understanding coastal sedimentation can inform land management decisions, marine resource reserves, and erosional processes during climate anomalies. KEYWORDS sand; beach morphology; wave energy; intertidal; seasonal; El Niño; 1 Blair Conklin El Niño Sedimentation Spring 2017 INTRODUCTION Beach morphology can undergo drastic changes over time. Wave energy plays an important role in the transport of sediments and the transformation of sandy beach systems (Moore et al. 1999; Charlier et al. 1998; Cooper et al. 2013). Many regions of the California coast are exposed to wave energies that are produced from storms formed in the southern and northern hemispheres of the Pacific Ocean. -

Geologic Boulder Map of Campus Has Been Created As an Educational Educational an As Created Been Has Campus of Map Boulder Geologic The

Adam Larsen, Kevin Ansdell and Tim Prokopiuk Tim and Ansdell Kevin Larsen, Adam What is Geology? Igneous Geo-walk ing of marine creatures when the limestone was deposited. It also contains by edited and Written Geology is the study of the Earth, from the highest mountains to the core of The root of “igneous” is from the Latin word ignis meaning fire. Outlined in red, numerous fossils including gastropods, brachiopods, receptaculita and rugose the planet, and has traditionally been divided into physical geology and his- this path takes you across campus looking at these ancient “fire” rocks, some coral. The best example of these are in the Geology Building where the stone torical geology. Physical geology concentrates on the materials that compose of which may have been formed at great depths in the Earth’s crust. Created was hand-picked for its fossil display. Campus of the Earth and the natural processes that take place within the earth to shape by the cooling of magma or lava, they can widely vary in both grain size and Granite is another common building stone used on campus. When compa- its surface. Historical geology focuses on Earth history from its fiery begin- mineral composition. This walk stops at examples showing this variety to help nies sell granite, they do not use the same classification system as geologists. nings to the present. Geology also explores the interactions between the you understand what the change in circumstances will do to the appearance Granite is sold in many different colours and mineral compositions that a Map Boulder Geologic lithosphere (the solid Earth), the atmosphere, the biosphere (plants, animals of the rock. -

Geology Teacher Guide

National Park Service Rocky Mountain U.S. Department of Interior Rocky Mountain National Park Geology Teacher Guide Table of Contents Rocky Mountain National Park.................................................................................................1 Teacher Guides..............................................................................................................................2 Rocky Mountain National Park Education Program Goals...................................................2 Geology Background Information Introduction.......................................................................................................................4 Setting.................................................................................................................................5 Tectonics of Rocky Mountain National Park..............................................................10 Glaciers of Rocky Mountain National Park................................................................16 Erosion History of Rocky Mountain National Park...................................................20 Foothills outside Rocky Mountain National Park......................................................21 Climate and Ecology of Rocky Mountain National Park..........................................22 Geology Resources Classroom Book List.......................................................................................................26 Glossary.............................................................................................................................28 -

Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms

Title 430 – National Soil Survey Handbook Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms Subpart A – General Information 629.0 Definition and Purpose This glossary provides the NCSS soil survey program, soil scientists, and natural resource specialists with landform, geologic, and related terms and their definitions to— (1) Improve soil landscape description with a standard, single source landform and geologic glossary. (2) Enhance geomorphic content and clarity of soil map unit descriptions by use of accurate, defined terms. (3) Establish consistent geomorphic term usage in soil science and the National Cooperative Soil Survey (NCSS). (4) Provide standard geomorphic definitions for databases and soil survey technical publications. (5) Train soil scientists and related professionals in soils as landscape and geomorphic entities. 629.1 Responsibilities This glossary serves as the official NCSS reference for landform, geologic, and related terms. The staff of the National Soil Survey Center, located in Lincoln, NE, is responsible for maintaining and updating this glossary. Soil Science Division staff and NCSS participants are encouraged to propose additions and changes to the glossary for use in pedon descriptions, soil map unit descriptions, and soil survey publications. The Glossary of Geology (GG, 2005) serves as a major source for many glossary terms. The American Geologic Institute (AGI) granted the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (formerly the Soil Conservation Service) permission (in letters dated September 11, 1985, and September 22, 1993) to use existing definitions. Sources of, and modifications to, original definitions are explained immediately below. 629.2 Definitions A. Reference Codes Sources from which definitions were taken, whole or in part, are identified by a code (e.g., GG) following each definition. -

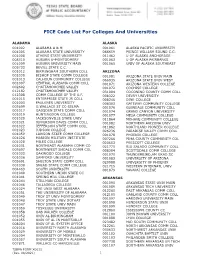

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

Frozen Ground

Frozen Ground Th e News Bulletin of the International Permafrost Association Number 32, December 2008 INTERNATIONAL PERMAFROST ASSOCIATION Th e International Permafrost Association, founded in 1983, has as its objectives to foster the dissemination of knowledge concerning permafrost and to promote cooperation among persons and national or international organisations engaged in scientifi c investigation and engineering work on permafrost. Membership is through national Adhering Bodies and Associate Members. Th e IPA is governed by its offi cers and a Council consisting of representatives from 26 Adhering Bodies having interests in some aspect of theoretical, basic and applied frozen ground research, including permafrost, seasonal frost, artifi cial freezing and periglacial phenomena. Committees, Working Groups, and Task Forces organise and coordinate research activities and special projects. Th e IPA became an Affi liated Organisation of the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) in July 1989. Beginning in 1995 the IPA and the International Geographical Union (IGU) developed an Agreement of Cooperation, thus making IPA an affi liate of the IGU. Th e Association’s primary responsibilities are convening International Permafrost Conferences, undertaking special projects such as preparing databases, maps, bibliographies, and glossaries, and coordinating international fi eld programmes and networks. Conferences were held in West Lafayette, Indiana, U.S.A., 1963; in Yakutsk, Siberia, 1973; in Edmonton, Canada, 1978; in Fairbanks, Alaska, 1983; in Trondheim, Norway, 1988; in Beijing, China, 1993; in Yellowknife, Canada, 1998, in Zurich, Switzerland, 2003, and in Fairbanks, Alaska, in 2008. Th e Tenth conference will be in Tyumen, Russia, in 2012.Field excursions are an integral part of each Conference, and are organised by the host Executive Committee 2008-2012 Council Members Professor Hans-W. -

Surveying the Great Sand Dunes National Park Overview

The Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve Unmanned Aircraft System Aerial Survey [email protected] [email protected] 720 259 0965 720 638 9656 wcecivil.com BlackSwiftTech.com 11582 Colony Row 2100 Central Ave., Ste. 102 Broomfield, CO 80021 Boulder, CO 80301 Figure 1: Final data product combining three dimensional data products with orthophoto collected by the Black Swift Technologies SwiftTrainerTM UAS Introduction • The placement and surveying of ground control points using GPS in an area inac- cessible to vehicles. A landmark set of Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) operations were conducted in the Great • Conducting a mission over an Area of In- Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve as part terest (AOI) several miles from the launch of a collaborative project to produce accurate, site while maintaining safe operations three-dimensional maps of the area. This re- through constant voice communications quired the combined eorts and expertise of between visual observers and the Pilot in Wohnrade Civil Engineers (WCE), Black Swift Command (PIC). Technologies (BST), UAS Colorado, and the National Park Service (NPS). Two flights were • Variable environmental factors, most no- successfully completed on October 19th 2016, tably gusting wind and contrasting shad- making Wohnrade Civil Engineers of Broomfield, ows. Colorado the first FAA licensed operator to use • The use of photogrammetry to process a an UAS to conduct a sanctioned mission over relatively homogeneous scene where fea- the Great Sand Dunes. Additionally, the photos ture detection and correlation across pho- collected during the flights allowed the team to tos was dicult. generate first-of-its-kind data products over a 1-square-mile area of the park. -

Reidentifying Depositional, Solifluction, “String Lobe” Landforms As Erosional, Topographic, Steps & Risers Formed by Paleo-Snowdunes in Pennsylvania, USA

Earth Sciences 2021; 10(3): 136-144 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/earth doi: 10.11648/j.earth.20211003.19 ISSN: 2328-5974 (Print); ISSN: 2328-5982 (Online) Reidentifying Depositional, Solifluction, “String Lobe” Landforms as Erosional, Topographic, Steps & Risers Formed by Paleo-Snowdunes in Pennsylvania, USA Michael Iannicelli Brooklyn College (C. U. N. Y.), Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Brooklyn, N. Y., USA Email address: To cite this article: Michael Iannicelli. Reidentifying Depositional, Solifluction, “String Lobe” Landforms as Erosional, Topographic, Steps & Risers Formed by Paleo-Snowdunes in Pennsylvania, USA. Earth Sciences. Vol. 10, No. 3, 2021, pp. 136-144. doi: 10.11648/j.earth.20211003.19 Received: May 13, 2021; Accepted: June 9, 2021; Published: June 30, 2021 Abstract: A controversy arises concerning relict, ubiquitous, depositional, solifluction, “string lobe” landforms in the Ridge and Valley province of Pennsylvania, reported by other investigators. A distinguishment is made here by defending an original interpretation of the particular landforms which identified these as snowdune meltwater-eroded depressions formed within colluvium during cold phases of the Pleistocene Epoch. Hence, the landforms are reassessed as “steps & risers” in this study which is jargon associated with nival erosion. The reidentification is warranted in the study because of multiple lines of evidence including: the landforms’ detailed geomorphology and sedimentology; the landforms having a highly, unusual, very repetitive, NE-SW orientation; and the landforms incurring a striking, gravity-defying, characteristic of running-water erosion repeatedly occurring irrespective of the steepest part of the general slope. Besides the evidence offered here, the study also gives insight, resolutions and re-confirmations in order to establish absolute identification while differentiating between discussed, periglacial, relict landforms. -

Pebble Count Methods

Pebble count methods The composition of the streambed and banks are using a zigzag pattern. In some cases only riffles are important facets of stream character, influencing channel sampled. Measure a minimum of 100 particles to obtain form and hydraulics, erosion rates, sediment supply, and a valid count. Usually less are collected if single channel other parameters. Each permanent reference site features are sampled. includes a basic characterization of bed and bank material. For studies of fish habitat, riparian ecosystems Start the collection at the lower end (downstream) of or stream hydraulics, the characterization of substrates your reach at one of the bankfull elevations (not and bank materials may require greater detail than can necessarily the present water level). Averting your gaze, be covered here. pick up the first particle touched by the tip of your index finger at the toe of your wader. Observations tell us that steep mountain streams with beds of boulders and cobbles act differently from low- Measure the intermediate axis (neither the longest nor gradient streams with beds of sand or silt. You can shortest of the three mutually perpendicular sides of document this difference by collecting representative each particle picked up). Measure embedded particles or samples of the bed materials using a procedure called a those too large to be moved in place. For these, pebble count. measure the smaller of the two exposed axes. Call out the measurement. The note taker tallies it by The most efficient basic technique is the Wolman Pebble size class and repeats it back for confirmation. Count. This requires an observer with a metric ruler who wades through the stream and a note taker who wades along side, or remains on the bank with the field book.