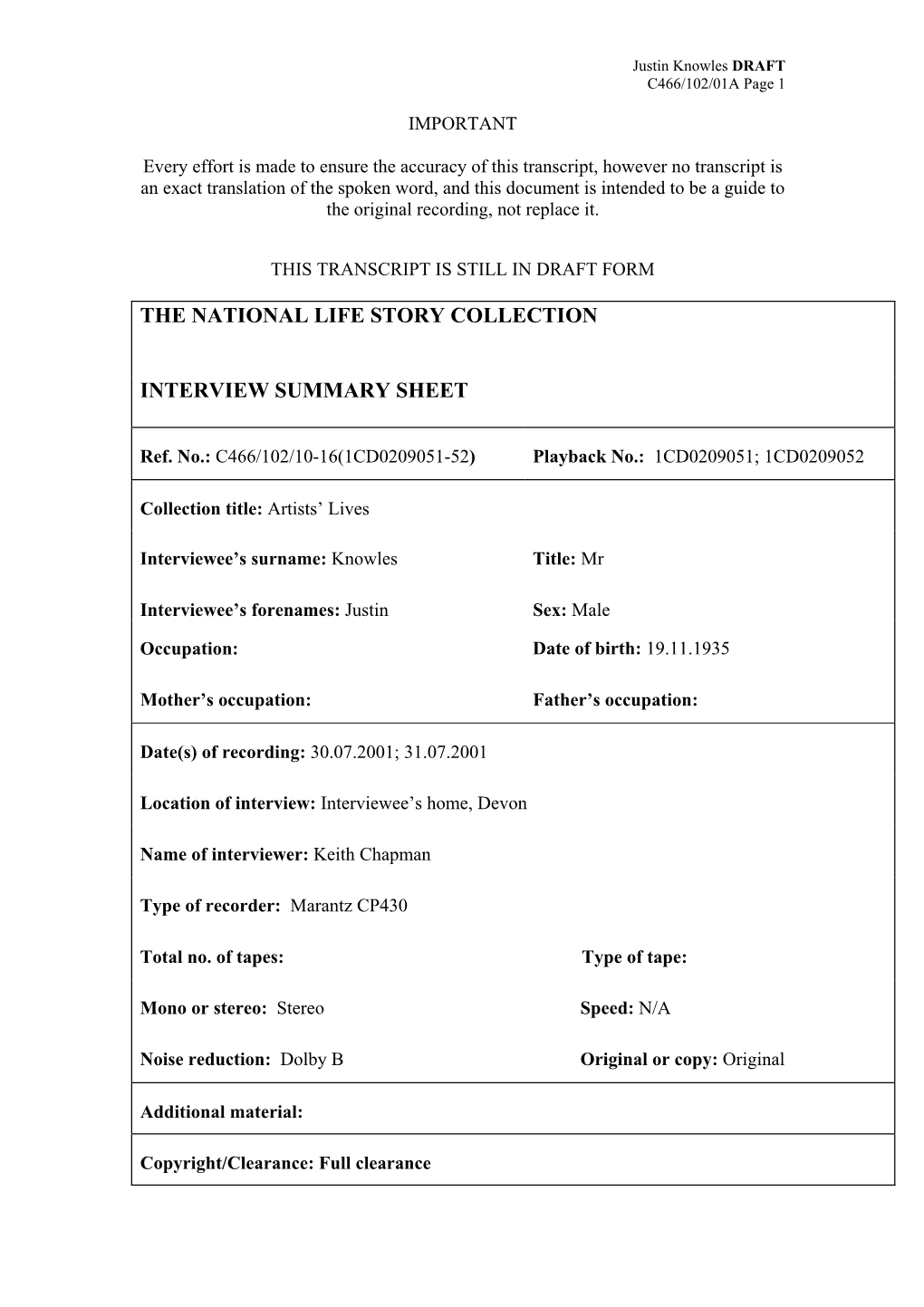

The National Life Story Collection Interview Summary Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Summerfield, Angela (2007). Interventions : Twentieth-century art collection schemes and their impact on local authority art gallery and museum collections of twentieth- century British art in Britain. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University, London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 'INTERVENTIONS: TWENTIETH-CENTURY ART COLLECTION SCIIEMES AND TIIEIR IMPACT ON LOCAL AUTHORITY ART GALLERY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS OF TWENTIETII-CENTURY BRITISH ART IN BRITAIN VOLUME If Angela Summerfield Ph.D. Thesis in Museum and Gallery Management Department of Cultural Policy and Management, City University, London, August 2007 Copyright: Angela Summerfield, 2007 CONTENTS VOLUME I ABSTRA.CT.................................................................................. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS •........••.••....••........•.•.•....•••.......•....•...• xi CHAPTER 1:INTRODUCTION................................................. 1 SECTION 1 THE NATURE AND PURPOSE OF PUBLIC ART GALLERIES, MUSEUMS AND THEIR ART COLLECTIONS.......................................................................... -

Exorcising the Fear British Sculpture from the 50S & 60S

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Exorcising the Fear British Sculpture from the 50s & 60s Private View: Tuesday 10 th January, 6 – 8pm 11 th January – 3 rd March 2012 Taking the sixtieth anniversary year of the XXVI Venice Biennale of 1952 as its starting point, Exorcising the Fear will explore a pivotal point in the history of British sculpture. Returning to the essay by Herbert Read which left an indelible mark on the history of art with the phrase ‘the geometry of fear’, the exhibition aims to recapture the excitement and vitality of the moment when eight young British sculptors – Robert Adams, Kenneth Armitage, Reg Butler, Geoffrey Clarke, Lynn Chadwick, Bernard Meadows, Eduardo Paolozzi and William Turnbull - burst onto an international scene and jump started a chain reaction that brought about a crucial sculptural renaissance in the history of British sculpture, the impact of which can still be felt today. Kenneth Armitage, Model for Krefeld Monument , 1956 Pangolin London are delighted to be able to show three rare works that are particularly closely related to those exhibited at the biennale (Lynn Chadwick’s Bull Frog , Reg Butler’s Young Girl and Geoffrey Clarke’s Man ) along with a superb collection of further works chosen for their direct relationship with those on display in Venice. The exhibition will include another rare Lynn Chadwick entitled Beast , which has not been seen in public since the 1950s. The work is over two metres high and made from welded iron and glass. Other highlights in the exhibition include Eduardo Paolozzi’s 1957 bronze Frog Eating a Lizard and William Turnbull’s minimal bronze with green patina on stone base, entitled Strange Fruit . -

Catalogue for Website.Indd

Cast in a Different Light: George Fullard and John Hoskin 2013 Introduction We follow with our eyes the development of the physical fact of a clenched hand, a crossed leg, a rising breast…until at the moment of recognition we realize that all this and more lies behind and makes up the reality of one woman or child during one second of their lives. And in this human tender sense, I would say that Fullard is one of the few genuine existentialist artists of today. He opens up for us the approach to and from the moment of awareness. John Berger on George Fullard, 1958 ¹ Vital and original…being a very distinct personality, he belongs to the animistic or magical trend in the now recognisable school of English sculpture. Herbert Read on John Hoskin, 1961 ² Woman with Earrings 1959 George Fullard Pencil At first glance, the artists featured in Cast in a Different Light have a good deal in common. Born in the early 1920s, they were both on active war service (Fullard in North Africa and Italy, Hoskin in Germany) and went on to make sculpture the focus of their creative practice. During the war years and immediately after, Henry Moore’s work attracted extraordinary international critical acclaim and, along with a generation of young sculptors, Fullard and Hoskin became part of what critics called the ‘phenomenon’ of postwar British sculpture.3 Through the 1960s, they both showed in gallery exhibitions such as the Tate’s British Sculpture in the Sixties (1965) and their work reached new audiences in the Arts Council’s iconic series of open-air sculpture exhibitions which toured public spaces and municipal parks up and down the country. -

Download the Catalogue

Vitalism iii 2017 We grew up in the 1950’s and 60’s when British post-war sculpture was the epitome of Modern Art. Linear, craggy forms with earthy textures and patinas defined post-war culture with a freedom that enabled and influenced our expectations of art as well as all subsequent sculptural movements. This new freedom is evident in the exploration of fresh techniques and materials and the instinctive ‘drawing in space’ made possible by the use of welded metal. Drawing was the essential preoccupation of almost all post-war artists, not only in the sense of Paul Klee’s famous words ‘taking a line for a walk’ but as a means of recreating personal worlds through the use of line. It could then so easily be reinterpreted in three dimensions: the fused and repeated lines of John Hoskin’s work, the implied lines modelled in clay by F.E. McWilliam and Kenneth Armitage, Lynn Chadwick’s geometric constructions or Reg Butler’s organic, curved, linear progressions. All these artists shared a determination to celebrate the physical process of ‘making’ by leaving it visible on the finished surface. It is this proximity to their creative journey that gives so much vitality to the sculptures of this time. Looking back now that more than 60 years have passed, it is difficult to imagine quite how avant-garde these sculptors and their work were. In their time, British journalists and commentators were not immediately enthused, unlike their continental colleagues who had embraced the New British Sculpture of the Venice Biennale of 1952. -

Bernard Meadows C466/013/F2999-A/Page 1

Bernard Meadows C466/013/F2999-A/Page 1 IMPORTANT Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. NATIONAL LIFE STORY COLLECTION ARTISTS' LIVES BERNARD MEADOWS interviewed by Tamsyn Woollcombe Bernard Meadows C466/013/F2999-A/Page 2 F2999 side A Bernard Meadows talking to Tamsyn Woollcombe at his home in London on the 3rd of November 1992. Tape 1. So, today we might start by talking a bit about your childhood, and I don't know whether you remember your grandparents, you know, back a generation, or whether you know anything about them. I know, or I knew, my paternal grandparents. My maternal grandparents died before I was born. Right. And where did the paternal grandparents live? In Norwich. In Norwich as well? Yes. Where you were born? Yes. Right. And so, did both your parents, did they come from Norwich? Yes. They did as well, oh right. It's a bit, it was a society where, people didn't move about much. Absolutely, no. Right, and so it was in Norwich itself that you lived, was it? Yes, well on the outskirts. Right. So did you find...did you used to go out into the country all round there? Bernard Meadows C466/013/F2999-A/Page 3 Yes. I used to paint. As a small child as well? No, not as a small child. But did you always have an artistic bent? It's the only thing I could do! (laughs) And were you one of several children? No, I just had a brother. -

PANGOLIN LONDON I N T R O D U C T I O N

PANGOLIN PANGOLIN LONDON 1 PANGOLIN LONDON INTR ODUCTION When I wrote the introduction to our last general catalogue almost six years ago from a small and bland offsite office, the idea of setting up a brand new sculpture gallery in King’s Cross seemed remarkably abstract. Not only was the building we were to inhabit still a shell but we were unfamiliar with the location and our audience. It was going to be a monumental leap into the unknown but as Kings Place underwent its rapid transformation from building site to elegant cultural hub it soon became apparent that this would be a perfect home for sculpture. Since then, we’ve held over forty exhibitions and established ourselves as one of the leading galleries dedicated to sculpture in the UK. To begin with, our strong affiliation with Pangolin Editions the bronze foundry caused some confusion. “Foundries should stick to what they know” one dismissive dealer told me but to simply show the wares of the foundry was never our intention. Rather the remit has always been to explore sculpture in all its forms and if the foundry’s expertise could help reinforce that then so much the better. Slowly, year on year we’ve proved our ability to deliver an interesting and dynamic exhibition programme ranging from cutting-edge contemporary to museum-quality historical with artists from the established to the emerging and from monumental surveys such as ‘Sculptors’ Drawings’ to intimate exhibitions. We’ve had shows that focus on the making process and those that push the boundaries of making not just in bronze but in silver and ceramic and even those that challenge the traditional pigeonholes of 2D and 3D to explore two and a half dimensions. -

Sculpture in the Home

PANGOLIN SCULPTURE IN THE HOME LONDON 1 SCULPTURE IN THE HOME One is apt to think of sculpture only as a monumental art closely connected with architecture so that the idea of an exhibition to show sculpture on a small scale as something to be enjoyed in the home equally with painting seemed worth while. Frank Dobson, Sculpture in the Home exhibition catalogue, 1946 Sculpture in the Home celebrates a series of innovative touring exhibitions of the same name organised in the 1940s and ‘50s first by the Artists International Association (AIA) and then the Arts Council. These exhibitions were intended to encourage viewers to reassociate themselves with sculpture on a smaller scale and also as an art form that could be enjoyed in a domestic environment. Works were shown not on traditional plinths or pedestals but in settings that included furniture and textiles of the day. With an estimated 2,000,000 homes destroyed by enemy action in the UK during World War II and around 60% of those in London one could be forgiven for thinking that the timing of these exhibitions was far from appropriate. However in many respects the exhibitions were perfectly timed and looking back sixty years later, offer us a unique insight into the exciting and rapid developments not only of sculpture and design but also manufacturing, and the re-establishment of the home as a sanctuary after years of hardship, uncertainty and displacement. As our exhibition hopes to explore the Sculpture in the Home exhibitions also offer us an opportunity to consider the cross-pollination between disciplines and the similarities of visual language that resulted. -

GALLERY PANGOLIN GALLERY PANGOLIN Gallery Pangolin Is Hidden Away on a River Bank in the Ancient Village of Chalford on the Edge of the Cotswolds

GALLERY PANGOLIN GALLERY PANGOLIN Gallery Pangolin is hidden away on a river bank in the ancient village of Chalford on the edge of the Cotswolds. The gallery opened in 1991 on what was once a Victorian industrial site at the heart of the Golden Valley. It grew from the need to represent the enormous variety of sculpture cast on the same premises by Pangolin Editions bronze foundry and continues an age-old association between art foundry and gallery. Now a well-established and recognized specialist in sculpture and related works on paper by both Modern and contemporary artists, Gallery Pangolin boasts an excellent reputation for works of quality and integrity. The gallery’s exciting annual programme includes themed and solo shows, publications, lectures, films and collaborations with public galleries and museums. Gallery Pangolin also co-ordinates commissions, curates major exhibitions of sculpture and acts as an agent for artists and collectors. CONTEMPORARY ANTHONY ABRAHAMS JON BUCK ANN CHRISTOPHER MICHAEL COOPER TERENCE COVENTRY STEVE DILWORTH ABIGAIL FALLIS SUE FREEBOROUGH JONATHAN KINGDON ANITA MANDL CHARLOTTE MAYER PETER RANDALL-PAGE ALMUTH TEBBENHOFF WILLIAM TUCKER ANTHONY ABRAHAMS b 1926 Anthony Abrahams’ carefully poised, enigmatic figures follow a tradition in British sculpture that began in the 1950’s with Armitage, Butler, Chadwick, Frink and Meadows and their contemporaries. The exaggeration of some features and the repression of others, unified by formal and textural qualities, give his sculpture a personal and expressive quality as if Prehistoric fertility symbols had been reborn in the contemporary world. His emblematic figures, caught in playful postures, remind us of ourselves and of those familiar to us. -

London Metropolitan Archives Public Sculpture

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 PUBLIC SCULPTURE LMA/4218 Reference Description Dates Photographs LMA/4218/01/001 Robert Adams 'Descending Forms' Eltham 19-- Green School 1 file LMA/4218/01/002 Dorothy Annan Mural Cayley School 19-- 1 file LMA/4218/01/003 Raymond Arnott 'Bird Bath' Alton Street, 19-- Lansbury Estate 1 file LMA/4218/01/004 Franta Belsky 'Lesson' Avebury Estate, Bethnal 19-- Green 1 file LMA/4218/01/005 Perry Brown Sculpture Coverdale Primary 19-- School, Shepherds' Bush 1 file LMA/4218/01/006 Ralph Brown 'Man and Child' Tulse Hill School, 19-- Upper Tulse Hill 1 file LMA/4218/01/007 Penelope Callender 'Boys playing leapfrog' 19-- Kynaston School, Marlborough Hill 1 file LMA/4218/01/008 Francis Carr 'Magic Garden' Mosaic Holman 19-- Hunt Primary School, New Kings Road 1 file LMA/4218/01/009 David Chapman ' The Seated Woman' 19-- Norwood County School 1 file LMA/4218/01/010 Siegfried Charoux 'The Neighbours' Quadrant 19-- Estate, Islington 1 file LMA/4218/01/011 Robert Chatworthy 'The Bull' Alton Estate, 19-- Roehampton 1 file LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 PUBLIC SCULPTURE LMA/4218 Reference Description Dates LMA/4218/01/012 Hubert Dalwood Sculpture Rutherford School 19-- 1 file LMA/4218/01/013 Robyn Denny 'Vitreous' Mosaic Boxgrove 19-- School 1 file LMA/4218/01/014 Professor Frank Dobson, C.B.E, A.R.A, 19-- Sculptured Fountain Cleveland Way Estate, Stepney 1 file LMA/4218/01/015 Alan Durst 'Sea Lions Pool' Greenlaw Street 19-- Home for the Aged 1 file LMA/4218/01/016 George Ehrlich 'Drinking Calf' Garrett Green 19-- School, Burnt Wood Lane 1 file LMA/4218/01/017 George Ehrlich 'Fawn with Goose' Savel House 19-- (Old People's Home), Bethnal Green 1 file LMA/4218/01/018 Merlyn Evans Decorative Screen Tower 19-- Hamlets School 1 file LMA/4218/01/019 Mary Fedden Mural Clapton Park Secondary 19-- School 1 file LMA/4218/01/020 Elizabeth Frink ' The Bird Man' Sedgehill 19-- School, Bellingham 1 file LMA/4218/01/021 Elizabeth Frink 'Eagle on a Column' 19-- Bredinghurst Special School 1 file LMA/4218/01/022 Professor A.H. -

Catalogue for Website.Pdf

Cast in a Different Light: George Fullard and John Hoskin 2013 Introduction We follow with our eyes the development of the physical fact of a clenched hand, a crossed leg, a rising breast…until at the moment of recognition we realize that all this and more lies behind and makes up the reality of one woman or child during one second of their lives. And in this human tender sense, I would say that Fullard is one of the few genuine existentialist artists of today. He opens up for us the approach to and from the moment of awareness. John Berger on George Fullard, 1958 ¹ Vital and original…being a very distinct personality, he belongs to the animistic or magical trend in the now recognisable school of English sculpture. Herbert Read on John Hoskin, 1961 ² Woman with Earrings 1959 George Fullard Pencil At first glance, the artists featured in Cast in a Different Light have a good deal in common. Born in the early 1920s, they were both on active war service (Fullard in North Africa and Italy, Hoskin in Germany) and went on to make sculpture the focus of their creative practice. During the war years and immediately after, Henry Moore’s work attracted extraordinary international critical acclaim and, along with a generation of young sculptors, Fullard and Hoskin became part of what critics called the ‘phenomenon’ of postwar British sculpture.3 Through the 1960s, they both showed in gallery exhibitions such as the Tate’s British Sculpture in the Sixties (1965) and their work reached new audiences in the Arts Council’s iconic series of open-air sculpture exhibitions which toured public spaces and municipal parks up and down the country. -

Leeds Arts Calendar Leeds Art Collections Fund

Leeds Arts Calendar Leeds Art Collections Fund This is an appeal to all who are interested in the Arts. The Leeds Art Collections Fund is the source of regular funds for buying works of art for the Leeds collection. We want more subscribing members to give one and a half guineas or upwards each year. Why not identify yourself with the Art Gallery and Temple Newsam; receive your Arts Calendar free each quarter; receive invitations to all functions, private views and organised visits to places of interest, by writing for an application form to the Hon Treasurer, E. M. Arnold Esq., Butterley .Ctree/, Leerls 10 7 he Libraries and Arls Sub-Committee 4rt Gallery and Temtste ~erosam House The Lord Mayor Alderman F. H. O'Donnell, J.t>. Alderman Mrs M. I'earce, J.p. Alderman H. S. Vick, J.p. Alderman J. T. V. Watson, Lt..a. Councillor Mrs G. Bray Councillor P. Crotty, LL.B. Councillor F. W. Hall Councillor E. Kavanagh Councillor S. Lee Councillor Mrs L. Lyons Councillor Mrs A. Malcolm Councillor A. S. Pedley, D.F.C. Co-opted Members Lady Martin Prof Quentin Bell, M.A. Mr W. T. Oliver, M.A. Mr Eric Taylor, R.E., A.R.O.A. Director Mr Robert S. Rowe, M.A., F.M.A. The Leeds Art Collection Fund President Vice-President The Rt Hon the Earl of Harewood, LL.D. Trustees Sir Herbert Read, D.s.o., M.c. Mr W. Gilchrist Mr C. S. Reddihough Commi ttee Mrs E. Arnold Prof Quentin Bell Mr George Black Mr W. -

Exorcising the Fear British Sculpture from the ‘50S and ‘60S

PANGOLIN EXORCISING THE FEAR BRITISH SCULPTURE FROM THE ‘50s anD ‘60s LONDON 1 EXORCISING THE FEAR hen Herbert Read wrote the introductory essay to the New Aspects Wof British Sculpture exhibition at the Venice Biennale sixty years ago, his phrase ‘the geometry of fear’ left an indelible mark on the history of British Sculpture. The term has since become synonymous with the eight sculptors that exhibited, yet whilst we can recall the artists that took part and Read’s indication that the works shown were spiky, aggressive and imbued with a collective guilt, many of us would struggle to envisage the exact works he was referring to. An exhibition that could recreate this renowned Biennale would present the perfect opportunity to reassess the validity of Read’s remarks. However with the works now scattered across the globe and some untraced, this may have to be a future project and for the meantime we must rely on the few archive images that remain and the brief catalogue. It is exciting to be able to include in this exhibition three rare works that are particularly closely related to those exhibited at the biennale (Lynn Chadwick’s Bull Frog, Reg Butler’s Young Girl and Geoffrey Clarke’sMan ) along with a superb collection of further works chosen for their direct relationship with those on display in Venice. A number of works from the subsequent generation of sculptors have also been included to highlight the immediate impact of the exhibition in the decade or so after this legendary biennale. Whilst Exorcising the Fear poses a number of broader questions such as whether the term the ‘geometry of fear’ can still be considered an appropriate description, the exhibition is primarily intended as a celebration - an opportu- nity to recapture the excitement and vitality of a moment when eight young British sculptors burst on to an international stage and jump-started a chain reaction that brought about a crucial sculptural renaissance in the history of British sculpture.