Slurs, Roles and Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Menaquale, Sandy

“Prejudice is a burden that confuses the past, threatens the future, and renders the present inaccessible.” – Maya Angelou “As long as there is racial privilege, racism will never end.” – Wayne Gerard Trotman “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” James Baldwin “Ours is not the struggle of one day, one week, or one year. Ours is not the struggle of one judicial appointment or presidential term. Ours is the struggle of a lifetime, or maybe even many lifetimes, and each one of us in every generation must do our part.” – John Lewis COLUMBIA versus COLUMBUS • 90% of the 14,000 workers on the Central Pacific were Chinese • By 1880 over 100,000 Chinese residents in the US YELLOW PERIL https://iexaminer.org/yellow-peril-documents-historical-manifestations-of-oriental-phobia/ https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/14/us/california-today-chinese-railroad-workers.html BACKGROUND FOR USA IMMIGRATION POLICIES • 1790 – Nationality and Citizenship • 1803 – No Immigration of any FREE “Negro, mulatto, or other persons of color” • 1848 – If we annex your territory and you remain living on it, you are a citizen • 1849 – Legislate and enforce immigration is a FEDERAL Power, not State or Local • 1854 – Negroes, Native Americans, and now Chinese may not testify against whites GERMAN IMMIGRATION https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/FT_15.09.28_ImmigationMapsGIF.gif?w=640 TO LINCOLN’S CREDIT CIVIL WAR IMMIGRATION POLICIES • 1862 – CIVIL WAR LEGISLATION ABOUT IMMIGRATION • Message to Congress December -

U·M·I University Microfilms International a Bell & Howell Information Compar,Y 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, M148106-1346 USA 3131761-4700 800/521-0600

Lexical decomposition in cognitive semantics. Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Saka, Paul. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 00:00:27 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/185592 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

EUGENE O'neill and the RHETORIC of ETHNICITY By

PIPE DREAMS AND PRIMITIVISM: EUGENE O’NEILL AND THE RHETORIC OF ETHNICITY by DONALD P. GAGNON A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Jack Moore, Ph.D. Anthony Kubiak, Ph.D. William Ross, Ph.D. Phillip Sipiora, Ph.D. Date of Approval April 8, 2003 Keywords: Modern drama, race, expressionism, capitalism © Copyright 2003, Donald P. Gagnon Dedication This work is dedicated to all of the valued teachers who have encouraged and challenged me to become the person and student I am. Special thanks to Dr. Jack Moore, teacher, collaborator, and great soul, for his personal and professional contributions to my work; to my partner Lance Smith for everything that may not be seen within these pages but remains an invaluable part of my studies and my life; and to my parents, Robert and Yvette Gagnon, whose patience, confidence, pride and love are as essential to my life as they have been to my education. Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge and express my appreciation to the following people who have contributed their energies, experience and knowledge to me and my work during this rewarding process: My committee members Dr. Rosalie Murphy Baum, Dr. William Ross, and Dr. Anthony Kubiak for their direction, suggestions, and interest both professional and personal; Dr. Richard Dietrich, for invaluable input; Dr. Jack Moore for marshalling these extraordinary forces and mitigating the stress that can easily accompany a project of such scope; Dr. -

3.1 What Is the Restaurant Game?

Learning Plan Networks in Conversational Video Games by Jeffrey David Orkin B.S., Tufts University (1995) M.S., University of Washington (2003) Submitted-to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY August 2007 © Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2007. All rights reserved. A uthor ........................... .............. Program in Media Arts and Sciences August 13, 2007 C ertified by ...................................... Associate Professor Thesis Supervisor Accepted by................................... Deb Roy 1 6lsimnhairperson, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students QF TECHNOLOGY SEP 14 2007 ROTCH LIBRARIES 2 Learning Plan Networks in Conversational Video Games by Jeffrey David Orkin Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences on August 13, 2007, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Abstract We look forward to a future where robots collaborate with humans in the home and workplace, and virtual agents collaborate with humans in games and training simulations. A representation of common ground for everyday scenarios is essential for these agents if they are to be effective collaborators and communicators. Effective collaborators can infer a partner's goals and predict future actions. Effective communicators can infer the meaning of utterances based on semantic context. This thesis introduces a computational cognitive model of common ground called a Plan Network. A Plan Network is a statistical model that provides representations of social roles, object affordances, and expected patterns of behavior and language. I describe a methodology for unsupervised learning of a Plan Network using a multiplayer video game, visualization of this network, and evaluation of the learned model with respect to human judgment of typical behavior. -

©2013 Tal Zalmanovich ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

©2013 Tal Zalmanovich ALL RIGHTS RESERVED SHARING A LAUGH: SITCOMS AND THE PRODUCTION OF POST-IMPERIAL BRITAIN, 1945-1980 by TAL ZALMANOVICH A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of Prof. Bonnie Smith And Approved by ---------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------- New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Sharing a Laugh: Sitcoms and the Production of Post-Imperial Britain, 1945-1980 By Tal Zalmanovich Dissertation Director: Bonnie Smith Sharing a Laugh examines the social and cultural roles of television situation comedy in Britain between 1945 and 1980. It argues that an exploration of sitcoms reveals the mindset of postwar Britons and highlights how television developed both as an industry and as a public institution. This research demonstrates how Britain metamorphosed in this period from a welfare state with an implicit promise to establish a meritocratic and expert-based society, into a multiracial, consumer society ruled by the market. It illustrates how this turnabout of British society was formulated, debated, and shaped in British sitcoms. This dissertation argues that both democratization (resulting from the expansion of the franchise after World War I) and decolonization in the post-World War II era, established culture as a prominent political space in which interaction and interconnection between state and society took place. Therefore, this work focuses on culture and on previously less noticed parties to the negotiation over power in society such as, media institutions, media practitioners, and their audiences. -

Slurring Words1 Luvell Anderson and Ernie Lepore

Slurring Words1 Luvell Anderson and Ernie Lepore Increasingly philosophers of language have been turning their attention to a phenomenon not much explored in the past. Racial and ethnic slurs have become an important topic, not only for the sake of theorizing about them adequately but for the implications they have on other well-worn areas of interest within the discipline. For instance, in “Reference, Inference, and The Semantics of Pejoratives” Timothy Williamson discusses the merits of Inferentialism by looking at its treatment of the slur ‘boche’. Mark Richard attempts to show that contrary to minimalism about truth, one is not making a conceptual confusion in holding that there are discursive discourses that are not truth-apt. Richard takes slurring statements to be one instance of this type, i.e. statements that are neither true nor false but represent the world to be a certain way. Others, like David Kaplan argue that slurs force us to expand our conception of meaning. Slurs also touch various other issues like descriptivism versus expressivism as well as the semantics/pragmatics distinction. Slurs’ effects on these issues make it difficult to ignore them and still give an adequate theory of language. Slurs are expressions that target groups on the basis of race (‘nigger’), nationality (‘kraut’), religion (‘kike’), gender (‘bitch’), sexual orientation (‘fag’), immigrant status (‘wetback’) and sundry other demographics. Xenophobes are not offended by slurs, but others are – with some slurs more offensive than others.2 Calling an Asian businessman ‘suit’ will not rouse the same reaction as calling him ‘chink’. Even co-extensive slurs vary in intensity of contempt. -

The Semantics of Racial Epithets1

The Semantics of Racial Epithets1 Christopher Hom Washington University, St. Louis I. Introduction Racial epithets are derogatory expressions, understood to convey contempt and hatred toward their targets. But what do they actually mean, if anything? There are two competing strategies for explaining how epithets work, one semantic and the other pragmatic. According to the semantic strategy, their derogatory content is fundamentally part of their literal meaning, and thus gets expressed in every context of utterance. This strategy honors the intuition that epithets literally say bad things, regardless of how they are used. According to the pragmatic strategy, their derogatory content is fundamentally part of how they are used, and results from features of the individual contexts surrounding their utterance. This strategy honors the intuition that epithets can be used for a variety of purposes, and that this complexity surrounding epithets precludes a univocal, context-independent explanation for how they work. Neither view is without difficulty, although to many the pragmatic strategy is prima facie more attractive. I shall argue, however, that the semantic strategy actually fares better on a number of criteria. In doing so, I shall motivate a particular semantic account of epithets that I call combinatorial externalism. The account has significant implications on theoretical, as well as, practical dimensions, providing new arguments against semantic externalism and radical contextualism, and for the exclusion of certain epithets from First Amendment speech protection. 1 Many thanks to José Bermudez, Eric Brown, John Doris, Jonathan Ellis, Robert May and the colloquium audiences at the Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, Washington University in St. -

The Ledger and Times, March 27, 1965

Murray State's Digital Commons The Ledger & Times Newspapers 3-27-1965 The Ledger and Times, March 27, 1965 The Ledger and Times Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt Recommended Citation The Ledger and Times, "The Ledger and Times, March 27, 1965" (1965). The Ledger & Times. 4770. https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt/4770 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Murray State's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Ledger & Times by an authorized administrator of Murray State's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. •P• r - t's - 26.1O65 )IS _P• isenplentio 7 • e • Selected As A Beat All Round Kentucky Community Newspaper eei , sm.................. i oration The Only Made Largest Circulation Afternoon Daily 1 S • - Chrysler Both In City In Murray And i las announced MurrAy Leas- - And In County [Calloway County - • Is Street, Mur- r for its it.. - ts Taybor Mu- International In Our &Sib Year Murray, Ky., Saturday Afternoon, March 27, 1965 Morris, Population 10,100 Vol. LXXXVI No. 73 ammo es Tow- United Press • •MWRIIM• the' appoint- James Garrison Is Rumen Lome. • • Hundreds Of Boys And Girls Named To Board Mrs. Joe Pace Is Honored irysoir Lessore Seen & Heard James Garrison, inanagePaf Ryan ippeintmere of I Are Available For Adoption Milk Company. Was today appointed With Dinner. Award Last Night ark -el another Around a member of the Murray-Gallo- mete of a nat. way County Airport Board by Coun- People who man the warmth and of • broken home Marry never Mrs ?Lary Pace was honored lad wee part et County of antomotive 'y Judge Robert 0. -

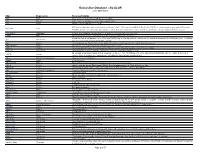

Racial Slur Database - by SLUR (Over 2500 Listed)

Racial Slur Database - By SLUR (over 2500 listed) Slur Represents Reasons/Origins 539 Jews Corresponds with the letters J-E-W on a telephone. 925 Blacks Police Code in Suburban LA for "Suspicious Person" 7-11 Arabs Work at menial jobs like 7-11 clerks. Refers to circumcision and consumerism (never pay retail). The term is most widely used in the UK where circumcision among non-Jews or non- 10% Off Jews Muslims is more rare, but in the United States, where it is more common, it can be considered insulting to many non-Jewish males as well. 51st Stater Canadians Canada is so culturally similar to the U. S. that they are practically the 51st state 8 Mile Whites When white kids try to act ghetto or "black". From the 2002 movie "8 Mile". Stands for American Ignorance as well as Artificial Intelligence-in other words...Americans are stupid and ignorant. they think they have everything A.I. Americans and are more advanced than every other country AA Blacks African American. Could also refer to double-A batteries, which you use for a while then throw away. Abba-Dabba Arabs Used in the movie "Betrayed" by rural American hate group. ABC (1) Chinese American-Born Chinese. An Americanized Chinese person who does not understand Chinese culture. ABC (2) Australians Aboriginals use it to offend white australians, it means "Aboriginal Bum Cleaner" Means American Born Confused Desi (pronounced day-see). Used by Indians to describe American-born Indians who are confused about their ABCD Indians culture. (Desi is slang for an 'countryman'). -

Thesis White South Africans in Colorado

THESIS WHITE SOUTH AFRICANS IN COLORADO: UNDERSTANDINGS OF APARTHEID AND POST-APARTHEID SOCIETY Submitted by Christine A. Weeber Department of Anthropology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Spring 2005 Copyright by Christine A. Weeber 2005 All Rights Reserved COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY March 31, 2005 WE HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER OUR SUPERVISION BY CHRISTINE A. WEEBER ENTITLED WHITE SOUTH AFRICANS IN COLORADO: UNDERSTANDINGS OF APARTHEID AND POST APARTHEID SOCIETY BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING IN PART REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS. Committee on Graduate Work Advisor 11 ABSTRACT OF THESIS WHITE SOUTH AFRICANS IN COLORADO: UNDERSTANDINGS OF APARTHEID AND POST-APARTHEID SOCIETY This pilot study focuses on the experiences of two white ethnic groups within the South African immigrant population, Afrikaners and English-speakers, who came of age during two different phases of apartheid, between 1958-1978 and 1979-1993. Race, ethnicity, generational standing, class, and nationalism remain important fault lines, so my analysis is structured to differentiate between the entrenchment and reproduction of these identities during apartheid and the disruption of these in the post-apartheid era and in people's migration to the U.S. Using a phenomenological approach, I investigate three issues: experiences of being white, the culture of apartheid, and immigration. Among the themes that emerged from my interviews are the "schizophrenic" nature of life under apartheid; guilt and responsibility; questions of truth, propaganda, and brainwashing; "Afropessimism" and racism; what it meant to be white under apartheid versus the present 'box of being white'; the 'push factors' of affirmative action and crime; and perspectives of race and racism in the U.S. -

Slave Narratives : a Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves, by Work Projects Administration This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Slave Narratives : A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from interviews with former slaves Florida Narratives Author: Work Projects Administration Release Date: May 7, 2004 [EBook #12297] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SLAVE NARRATIVES: FLORIDA *** Produced by Andrea Ball and PG Distributed Proofreaders. Produced from images provided by the Library of Congress, Manuscript Division. [TR: ***] = Transcriber Note [HW: ***] = Handwritten Note SLAVE NARRATIVES A Folk History of Slavery in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves TYPEWRITTEN RECORDS PREPARED BY THE FEDERAL WRITERS' PROJECT 1936-1938 ASSEMBLED BY THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS PROJECT WORK PROJECTS ADMINISTRATION FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA SPONSORED BY THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON 1941 VOLUME III FLORIDA NARRATIVES Prepared by the Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration for the State of Florida INFORMANTS Anderson, Josephine Andrews, Samuel Simeon Austin, Bill Berry, Frank Biddie, Mary Minus Boyd, Rev. Eli Boynton, Rivana Brooks, Matilda Bynes, Titus Campbell, Patience Clayton, Florida Coates, Charles Coates, Irene Coker, Neil Davis, Rev. Young Winston Dorsey, Douglas Douglass, Ambrose Duck, Mama Dukes, Willis Everett, Sam and Louisa Gaines, Duncan Gantling, Clayborn Gragston, Arnold Gresham, Harriett Hall, Bolden Hooks, Rebecca Jackson, Rev. -

Common Features of English Taboo Words

COMMON FEATURES OF ENGLISH TABOO WORDS A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Program in English Language Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Magister Humaniora (M.Hum) in English Language Studies by Shirley Maya Argasetya Student Number: 046332010 THE GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE STUDIES SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2009 i A THESIS COMMON FEATURES OF ENGLISH TABOO WORDS by Shirley Maya Argasetya Students Number: 046332010 Approved by Prof. Dr. Soepomo Poedjosoedarmo Advisor Yogyakarta, September 28, 2009 ii A THESIS COMMON FEATURES OF ENGLISH TABOO WORDS by Shirley Maya Argasetya Students Number: 046332010 was Defended before the Thesis Committee and Declared Acceptable Thesis Committee Chairperson : Drs. F.X. Mukarto, M.S., Ph.D. ...……………………. Secretary : Dr. B.B. Dwijatmoko, M.A. ...……………………. Member : Dr. J. Bismoko …...…………………. Member : Prof. Dr. Soepomo Poedjosoedarmo …...…………………. Yogyakarta, September 28, 2009 The Graduate Program Director Sanata Dharma University Prof. Dr. A. Supratiknya iii STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY This is to certify that all the ideas, phrases, and sentences, unless otherwise stated, are the ideas, phrases, and sentences of the thesis writer. The writer understands the full consequences including degree cancellation if she took somebody else’s ideas, phrases, or sentences without a proper references. Yogyakarta, August 22, 2009 Shirley Maya Argasetya iv LEMBAR PERNYATAAN PERSETUJUAN PUBLIKASI KARYA ILMIAH UNTUK KEPENTINGAN AKADEMIS Yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini, saya mahasiswa Universitas Sanata Dharma : Nama : Shirley Maya Argasetya Nomor Mahasiswa : 046332010 Demi pengembangan ilmu pengetahuan, saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma karya ilmiah saya yang berjudul : Common Features of English Taboo Words beserta perangkat yang diperlukan (bila ada).