1. Letter to Bal Kalelkar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10CC Dreadlock Holiday 98 Degrees Because of You Aaron Neville Don

10CC My Love My Life Dreadlock Holiday One Of Us Our Last Summer 98 Degrees Rock Me Because Of You S.O.S. Slipping Through My Fingers Aaron Neville Super Trouper Don't Know Much (Duet Linda Ronstad) Take A Chance On Me For The Goodtimes Thank You For The Music The Grand Tour That's Me The Name Of The Game Aaron Tippin The Visitors Ain't Nothin' Wrong With The Radio The Winner Takes It All Kiss This Tiger Two For The Price Of One Abba Under Attack Andante, Andante Voulez Vous Angel Eyes Waterloo Another Town, Another Train When All Is Said And Done Bang A Boomerang When I Kissed The Teacher Chiquitita Why Did It Have To Be Me Dance (While The Music Still Goes On) Dancing Queen Abc Does Your Mother Know Poison Arrow Dum Dum Diddle The Look Of Love Fernando Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midnight) Ac Dc Happy New Year For Those About To Rock Hasta Manana Have A Drink On Me He Is Your Brother Highway To Hell Hey Hey Helen Who Made Who Honey Honey Whole Lotta Rosie I Do, I Do, I Do You Shook Me All Night Long I Have A Dream I Let The Music Speak Ace Of Base I Wonder All That She Wants If It Wasn't For The Nights Beautiful Life I'm A Marionette Cruel Summer I've Been Waiting For You Don't Turn Around Kisses Of Fire Life Is A Flower Knowing Me Knowing You Lucky Love Lay All Your Love On Me The Sign Lovers(Live A Little Longer) Wheel Of Fortune Mamma Mia Money Money Money Ad Libs The Engelstalige Karaoke Holding de Riddim Entertainment Pagina 1 Boy From New York City Theme From Moonlighting Adele Al Jolson Don't You Remember Avalon I Set Fire -

50S 60S 70S.Txt 10Cc - I'm NOT in LOVE 10Cc - the THINGS WE DO for LOVE

50s 60s 70s.txt 10cc - I'M NOT IN LOVE 10cc - THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE A TASTE OF HONEY - OOGIE OOGIE OOGIE ABBA - DANCING QUEEN ABBA - FERNANDO ABBA - I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO ABBA - KNOWING ME KNOWING YOU ABBA - MAMMA MIA ABBA - SOS ABBA - TAKE A CHANCE ON ME ABBA - THE NAME OF THE GAME ABBA - WATERLOU AC/DC - HIGHWAY TO HELL AC/DC - YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG ACE - HOW LONG ADRESSI BROTHERS - WE'VE GOT TO GET IT ON AGAIN AEROSMITH - BACK IN THE SADDLE AEROSMITH - COME TOGETHER AEROSMITH - DREAM ON AEROSMITH - LAST CHILD AEROSMITH - SWEET EMOTION AEROSMITH - WALK THIS WAY ALAN PARSONS PROJECT - DAMNED IF I DO ALAN PARSONS PROJECT - DOCTOR TAR AND PROFESSOR FETHER ALAN PARSONS PROJECT - I WOULDNT WANT TO BE LIKE YOU ALBERT, MORRIS - FEELINGS ALIVE N KICKIN - TIGHTER TIGHTER ALLMAN BROTHERS - JESSICA ALLMAN BROTHERS - MELISSA ALLMAN BROTHERS - MIDNIGHT RIDER ALLMAN BROTHERS - RAMBLIN MAN ALLMAN BROTHERS - REVIVAL ALLMAN BROTHERS - SOUTHBOUND ALLMAN BROTHERS - WHIPPING POST ALLMAN, GREG - MIDNIGHT RIDER ALPERT, HERB - RISE AMAZING RHYTHM ACES - THIRD RATE ROMANCE AMBROSIA - BIGGEST PART OF ME AMBROSIA - HOLDING ON TO YESTERDAY AMBROSIA - HOW MUCH I FEEL AMBROSIA - YOU'RE THE ONLY WOMAN AMERICA - DAISY JANE AMERICA - HORSE WITH NO NAME AMERICA - I NEED YOU AMERICA - LONELY PEOPLE AMERICA - SISTER GOLDEN HAIR AMERICA - TIN MAN Page 1 50s 60s 70s.txt AMERICA - VENTURA HIGHWAY ANDERSON, LYNN - ROSE GARDEN ANDREA TRUE CONNECTION - MORE MORE MORE ANKA, PAUL - HAVING MY BABY APOLLO 100 - JOY ARGENT - HOLD YOUR HEAD UP ATLANTA RHYTHM SECTION - DO IT OR DIE ATLANTA RHYTHM SECTION - IMAGINARY LOVER ATLANTA RHYTHM SECTION - SO IN TO YOU AVALON, FRANKIE - VENUS AVERAGE WHITE BD - CUT THE CAKE AVERAGE WHITE BD - PICK UP THE PIECES B.T. -

Non-Cooperation 1920-1922: Regional Aspects of the All India Mobilization

NON-COOPERATION 1920-1922: REGIONAL ASPECTS OF THE ALL INDIA MOBILIZATION Ph.D Thesis Submitted by: SAKINA ABBAS ZAIDI Under the Supervision of Dr. ROOHI ABIDA AHAMAD, Associate Professor Centre of Advance Study Department of History Aligarh Muslim University Aligarh(India) 2016 Acknowledgements I am immensely thankful to ‘Almighty Allah,’ and Ahlulbait (A.S), for the completion of my work in spirit and letter. It is a pleasant duty for me to acknowledge the kindness of all my teachers, friends, well-wishers and family with whose help and advice I was able to complete this work, as it is undeniable true that thesis writing involves other aiding you directly or indirectly. First and foremost, beholden to my supervisor, Dr. Roohi Abida Ahmed, for her encouragement, moral support, inspiring suggestions and excellent guidance. The help she extended to me was more than what I deserve. She always provided me with constructive and critical suggestions. I felt extraordinary fortunate with the attentiveness I was shown by her. I indeed consider myself immensely blessed in having someone so kind and supportive as my supervisor from whom I learnt a lot. A statement of thanks here falls very short for the gratitude I have for her mentorship. I gratefully acknowledge my debt to Professor Tariq Ahmed who helped a lot in picking up slips and lapses in the text and who has been a constant source of inspiration for me during the course of my study. I am thankful to Professor Ali Athar, Chairman and Coordinator, Centre of Advanced Study, Department of History, AMU, Aligarh for being always receptive and supportive. -

URBAN ISLANDS Vol 1

Urban Island (n): a post industrial site devoid of program or inhabitants; a blind spot in the contemporary city; an iconic ruin; dormant infrastructure awaiting cultural inhabitation. ii iii iv v vi CUTTINGS URBAN ISLANDS vol 1 EDITED BY JOANNE JAKOVICH Copyright URBAN ISLANDS vol 1 : CUTTINGS Published by SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS University of Sydney Library www.sup.usyd.edu.au © 2006 Urban Islands Project: Joanne Jakovich , Olivia Hyde, Thomas Rivard © of individual chapters is retained by the contributors Editor: Joanne Jakovich [email protected] Preface: GEOFF BAILEY Assistant Editors: Jennifer Gamble, Jane HYDE layout: Joanne Jakovich photography: kota arai Cover Design: Olivia Hyde Cover Photo: Samantha Hanna PART III Design: Nguyen Khang Tran (Sam) URBAN ISLANDS PROJECT WWW.URBANISLANDS.INFO I NAUGURAL URBAN ISLANDS STUDIO , REVIEW + SYMPOSIUM ORGANISED BY : OLIVIA HYDE, THOMAS RIVARD, JOANNE JAKOV ICH & I NGO KUMIC, AUGUST 2006 Reproduction and Communication for other purposes : Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may b e reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University viii Copyright Press at the address b elow: Sydney University Press Fisher Library F03 University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] ISBN 1–920898–55–7 Individual papers are available electronically through the Sydney e-Scholarship Repository at: ses.library.usyd.edu.au Printed in Australia at the University Publishing Service, University of Sydney. ix PREFACE Describing Cockatoo Island as a post-industrial site is a little like examining a Joseph Cornell box and not noticing its contents. -

Organic GROWER Growers Alliance

The Summer 2010 No.12 ORGANICThe journal of the Organic GROWER Growers Alliance IN THIS ISSUE The weather, whatever News................................................2 “ It’s a nice start to the day after yesterday’s disappointing cloud and rain, with good long spells of bright sunshine . “. Actually OGA.event.-.plant.propagation....12 you didn’t have enough rain yesterday to damp the dust down and so far as you can see the only moisture your crops are going to get Bavarian.organic.vegetables.........13 are your own salt tears. All that investment – planning, materials, cultivation, planting, weed control, all that hope and all that labour and the only outcome that looks likely is a bigger hole in your bank Using.wheel.hoes...........................14 balance. It’s not sun bathing you’re after, it’s rain. Still - it is only the weather forecast, sometimes irritating, often misleading, but not to Nature.notes..................................16 be taken too seriously. Growing.jobs.-a.workforce.guide..17 The weather, on the other hand, that’s different and we can hardly help but take it seriously. We can’t do anything about it, other than Growing.food,.absorbing.carbon...20 perhaps mitigating its effects, yet it rules our lives, those of us who make our living by what we can produce from the soil. To our fellow citizens it may just represent a decision as to whether or not to Drilling.sweetcorn........................22 carry an umbrella, or whether to have a barbecue outdoors or sit in front of the widescreen indoors. The subtleties of what the heavens Biodynamic.plant.breeding...........26 send down on us and even (perhaps especially) the gut-wrenching, nerve-coursing emotions that it engenders in the psyche of the food Christmas.trees..............................28 producer, are entirely lost on the rest of the world. -

An Analysis of Jhumpa Lahiri's Fiction

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Eldorado - Ressourcen aus und für Lehre, Studium und Forschung Immigration: ‘A Lifelong Pregnancy’? An Analysis of Jhumpa Lahiri’s Fiction Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Würde des Doktors der Philosophie in der Fakultät Kulturwissenschaften der Technischen Universität Dortmund vorgelegt von Ramona-Alice Bran 1. Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Walter Grünzweig 2. Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Randi Gunzenhäuser Dortmund 2014 Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Prof. Dr. Walter Grünzweig for accepting me as his PhD student and for believing I could pull this through, for having had the patience to read my work and guide my steps when I was stuck, for providing so much help and insight, and for having taken the time to get to know me. I am immensely grateful to you. I am also thankful to the other wonderful people I have met at the American Studies Department from Dortmund. First and foremost, thank you Prof. Dr. Randi Gunzenhäuser for having read my dissertation. I really appreciate your humor and witty comments. Thank you: Sina, Elena, Mario, Johanna, Julia, Eriko and Martina for your friendship and support. Looking back, I realize I have had such an enriching experience and I can only hope we will keep in touch. All my love goes to my closest friends back home who have stood by me all along. Thanks, in particular, to Remus, the one with whom I have embarked on this unexpected adventure. This five-year long journey has taken us to different places, but what an amazing experience it has been! Most of all, thanks to my family who has always believed in me. -

Covers 569 Songs, 2 Days, 2.91 GB

Covers 569 songs, 2 days, 2.91 GB Name Time Album Artist Abracadabra 3:42 14:59 Sugar Ray Act Nice and Gentle 2:56 Give the People What We Want: Son… Larry Barrett The Adventures of Grandmaster Fla… 5:46 The Document DJ Andy Smith & Grandmaster Flash After the Love Has Gone 3:58 Somewhere in Time Donny Osmond Against All Odds 4:13 The Postal Service Alcohol 3:26 Give the People What We Want: Son… The Murder City Devils Alex Chilton 3:18 Left of the Dial - a Pop Tribute to t… The Marlowes Alison (Live) 3:47 Cover Me Badd - EP Butch Walker Always Something There to Remind… 3:39 Heads Are Gonna Roll The Hippos Always Something There to Remind… 4:13 Cover Me Badd - EP Butch Walker Ana Ng 3:23 Hello Radio: The Songs of They Mig… Self And I Ran 4:25 Punk Goes 80's - Compilation Hidden in Plain View And She Was 3:49 Sky High Keaton Simons and your bird can sing 1:55 extras jam And Your Bird Can Sing 2:08 Under the Covers Vol. 1 Matthew Sweet & Susanna Hofs (The Angels Wanna Wear My) Red S… 2:40 A Tribute to Elvis Costello Patrik Tanner Annie Get Your Gun 3:39 Happy Doing What We're Doing Elizabeth McQueen and the Firebra… Another Girl Another Planet 2:41 Blink-182: Greatest Hits Blink-182 Another Nail for My Heart 2:39 Ultra Feel, Vol. 1 Rubber Ashes to Ashes 5:01 Ashes to Ashes - Single Grant-Lee Phillips & The Section Q… Ashes to Ashes 4:32 Saturnine Martial & Lunatic Tears for Fears Athena 4:15 Who's Not Forgotten, FDR's Tribute… Grandfabric B*****s Ain't S**t 3:55 B*****s Ain't S**t - Single Ben Folds Baba O'Riley 4:56 Who's Not Forgotten, FDR's Tribute… Guided by Voices .. -

David Hardiman.P65

NMML OCCASIONAL PAPER HISTORY AND SOCIETY New Series 61 Nonviolent Resistance in India 1916–1947 David Hardiman Emeritus Professor of History, University of Warwick, UK Nehru Memorial Museum and Library 2014 NMML Occasional Paper © David Hardiman, 2014 All rights reserved. No portion of the contents may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the author. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author and do not reflect the opinion of the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library Society, in whole or part thereof. Published by Nehru Memorial Museum and Library Teen Murti House New Delhi-110011 e-mail : [email protected] ISBN : 978-93-83650-43-9 Price Rs. 100/-; US $ 10 Page setting & Printed by : A.D. Print Studio, 1749 B/6, Govind Puri Extn. Kalkaji, New Delhi - 110019. E-mail : [email protected] NMML Occasional Paper Nonviolent Resistance in India 1916–1947* David Hardiman Introduction In recent years, nonviolent forms of protest have been used, to a powerful effect, in bringing down some highly oppressive regimes, as well as in fighting for civil rights and other issues within many societies. There has been a wave of books in response, mainly coming from a tradition of writing that originated in peace studies, but has evolved into what we can now distinguish as a separate field—that of the study of the strategy of nonviolent protest, or, as it is sometimes described, ‘people power’. This literature aims to reveal the growing efficacy in modern times of nonviolent methods as against violent ones. It examines the strategies that have been adopted in such movements, with the emphasis being on discovering the most effective techniques and methods that can be applied in future campaigns. -

Unsung Women Heroes in Indian Freedom Struggle: an Acknowledgement

UNSUNG WOMEN HEROES IN INDIAN FREEDOM STRUGGLE: AN ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Urmila Sharma Dept. of Social Sciences Maharaja College Debari, Udaipur, Rajasthan Email: [email protected] Mobile No. 9828507223 ABSTRACT This paper is all about unsung women heroes in Indian Freedom Struggle with specific reference to Rajasthan State in India. It is an effort by the author to acknowledge those women heroes who participated in the IndianFreedom Movement even though all of them belong to very poor and mediocre family background. Still they have shown courage and confidence to come forward and made a significant contribution in theFreedom Movement and Bijolia Kisan Andolan against Jagirdari Pratha started in Rajasthan in the leadership of Vijay Singh Pathik, Manikaya Lal Verma and Sadhu Sita Ram. They have made women class awakened for their rights against the royal state. In future, this development contributed in producing many women leaders in Rajasthan State. In this paper the author is going to present unsung stories of women heroeslike Ganga Bai, Nayarani Devi Verma, Bharti Devi Vajpayee, Santa Trivedi, Smt. Gorya Devi, Smt. Anjana Deve Choudhary, Shakuntala Trivedi, Bhagvati Devi, Durga Devi, Ratan Shastri, Nagendra Bala, who participated in the Indian Freedom Struggle and left their footprints of their sacrifice and success in getting freedom in India. Briefly mentioning the contribution of one out of eleven women like Narayani Devi Verma inspired by Bijolia Andolan, who had worked for women education and social work. In 1942, she went to jail in Parjamandal Movement. Later on, she established a women center in Bhilwara to make women aware about their rights. -

Personal Profile

PERSONAL PROFILE Name : Mrs. Sujata Malik Subject : Chemistry Date of Birth : 11.10.1975 Educational Qualifications Name of Examination Board/ University Passing Year Division M.Sc. CCS University, Meerut 1996 First GATE 2001 First CSIR-UGC(NET) 2004 Qualified Ph.D.(Chemistry) CCS University, Meerut Pursuing Mobile number 09412803374, 6397497156 Present Designation Assistant Professor, Department of Chemistry DN College, Meerut (Uttar Pradesh) Total Teaching Experience : UG Classes 10 yrs approx. PG Classes 10 yrs approx *Assistant Professor appointed by UP Higher Education Commission Allahabad From 14 Feb. 2009 to 31 August, 2016 BSA College, Mathura From 1 Sept, 2016 till date DN College, Meerut 1 AWARDS/SAMMAN RECEIVED 1. Best Teacher of the Year in Chemistry (2019) ( Vedant Academics Bankok Award, Thailand; International Association of Research and Development Organisation , IARDO) RESEARCH PAPER PRESENTED IN SEMINAR 1. National Seminar (Deliberative Research) on Need for Professional & Technical Educational Education in India was held on 27th Feb, 2011 at Amit Bal Bhavan, Firozabad. 2. National Seminar (UP Government Sponsored) on Human Rights Movements in India and Challenges before National Security was held on 15th and 16th March, 2011 at Hemwati Nandan Bahuguna Government PG college, Naini, Allahabad. The paper presented was Adhunik Bharat me Bal Vivah: Ek Samajik Nasur 3. National Seminar (U.G.C. sponsored) on Human Rights: concept, meaning and development was held on 27th and 28th Feb. 2012at Dayanand Arya Kanya (PG) College, Moradabad. The paper presented was Enthronement of Rights for temporary teachers- The need of the day. 4. International Seminar (U.G.C. sponsored) on Post Modernism: Dimensions and challenges was held on 1st , 2nd and 3rd March,2012 , SV PG College, Aligarh (UP) The paper presented was Value Education: The Only Way on the Road to the Quality of Life in Post Modernism 5. -

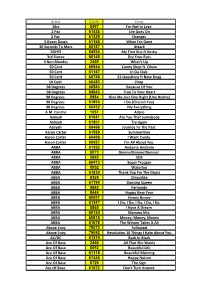

Karaoke List

Artist Code Song 10cc 8497 I'm Not In Love 2 Pac 61426 Life Goes On 2 Pac 61425 Changes 3 Doors Down 61165 When I'm Gone 30 Seconds To Mars 60147 Attack 3OH!3 84954 My First Kiss ft Kesha 3rd Storee 60145 Dry Your Eyes 4 Non Blondes 2459 What's Up 50 Cent 60944 Candy Shop ft. Olivia 50 Cent 61147 In Da Club 50 Cent 60748 21 Questions ft Nate Dogg 50 Cent 60483 Pimp 98 Degrees 60543 Because Of You 98 Degrees 84943 True To Your Heart 98 Degrees 8984 Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) 98 Degrees 61890 I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees 60332 My Everything A.M. Canche 1051 Adoro Aaliyah 61681 Are You That Somebody Aaliyah 61801 Try Again Aaliyah 60468 Journey To The Past Aaron Carter 61588 Summertime Aaron Carter 60458 I Want Candy Aaron Carter 60557 I'm All About You ABBA 61352 Andante Andante ABBA 8073 Gimme!Gimme!Gimme! ABBA 2692 SOS ABBA 60413 Super Trooper ABBA 8952 Waterloo ABBA 61830 Thank You For The Music ABBA 8369 Chiquitita ABBA 61199 Dancing Queen ABBA 8842 Fernando ABBA 8444 Happy New Year ABBA 60001 Honey Honey ABBA 61347 I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do ABBA 8865 I Have A Dream ABBA 60134 Mamma Mia ABBA 60818 Money, Money, Money ABBA 61678 The Winner Takes It All Above Envy 79073 Followed Above Envy 79092 Revolution 10 Things I Hate About You AC/DC 61319 Back In Black Ace Of Base 2466 All That She Wants Ace Of Base 8592 Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 61118 Beautiful Morning Ace Of Base 61346 Happy Nation Ace Of Base 8729 The Sign Ace Of Base 61672 Don't Turn Around Acid House Kings 61904 This Heart Is A Stone Acquiesce 60699 Oasis Adam -

9789955196679.Pdf (2.187Mb)

SOCIAL WORK WITH CHILDREN AND YOUTH: INTERCULTURAL AND INTERNATIONAL ASPECT Raminta Bardauskienė Leta Dromantienė Vida Gudžinskienė Asta Railienė Daiva Skučienė Jautrė R. Šinkūnienė Irena Žemaitaitytė MYKOLO ROMERIO UNIVERSITETAS Raminta Bardauskienė, Leta Dromantienė, Vida Gudžinskienė, Asta Railienė, Daiva Skučienė, Jautrė R. Šinkūnienė, Irena Žemaitaitytė SOCIAL WORK WITH CHILDREN AND YOUTH: INTERCULTURAL AND INTERNATIONAL ASPECT Vilnius 2014 The project "Preparing and implementing joint Master‘s degree programme "Social work with children and youth"", project No. VP1-2.2-ŠMM-07-K-02-054, is co-financed by the Republic of Lithuania and the European Union. Reviewers Doc. dr. Vilmantė Alkesienė (Lithuanian University of Educational Sciences) Doc. Angelė Čepėnaitė (Mykolas Romeris University) Authors contribution: Raminta Bardauskienė – 2,3 author’s sheet Leta Dromantienė – 0,7 author’s sheet Vida Gudžinskienė – 4 author’s sheet Asta Railienė – 3,9 author’s sheet Daiva Skučienė – 2,4 author’s sheet Jautrė R. Šinkūnienė – 2,8 author’s sheet Irena Žemaitaitytė – 1,1 author’s sheet Publishing was approved by: Faculty of Social Technologies of Mykolas Romeris University (18th of March 2014, No. 1STH-31). Institute of Educational Sciences and Social Work of Mykolas Romeris University (12th of March 2014, No. 1ESDI-3). Bachelor study programmes committees of Career Counselling Pedagogy, Sociocultural Education, Social Pedagogy and the Master study programmes committees of Educational Science for Law, Educational Science for Entrepreneurship, Management of Educational Technologies, Health Education of Mykolas Romeris University (13th of March, 2014, No. 3/10-228). Publication Review and Approval Commission of Mykolas Romeris University (10th of March 2014, No. 2L-9). All rights reserved.