Ron Silliman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Verandert Altijd

verandert altijd verandert Alles Kaikki Vše Alles verandert altijd is een onmisbaar instrument voor de literair vertaler in opleiding en de beginnende en gevorderde professional bij het vertalen in en uit het Nederlands. Voor het eerst worden Everything hier alle belangrijke aspecten van het literair vertalen helder en bevattelijk samengebracht: de zakelijke en financiële aspecten, de basiskennis en vaardigheden die deze activiteit veronderstelt, vertalen op literair Perspectieven Tutto de algemene kernbegrippen en uitdagingen, het vertalen van de traditionele literaire genres, maar ook van kinder- en jeugd- literatuur, literaire non-fictie en filosofie, en de ‘nazorg’ in de vorm Alles van revisie, marketing en promotie. Het boek is een initiatief van het Expertisecentrum Literair verandert altijd Vertalen (ELV), en bevat bijdragen van 23 vertaalexperts (weten- schappers, opleiders en vertalers), onder eind redactie van Lieven D’hulst en Chris Van de Poel. Beiden zijn lid van het wetenschap- Perspectieven pelijk comité van het ELV, een partnerschap van de Taalunie, de KU Leuven en de Universiteit Utrecht, in samenwerking met het (red.) de Poel en Chris Van D’hulst Lieven Nederlands Letterenfonds en het Vlaams Fonds voor de Letteren. op literair vertalen Lieven D’hulst is gewoon hoogleraar Franstalige letter kunde en vertaalwetenschap aan de Letterenfaculteit van de KU Leuven. Lieven D’hulst en Chris Van de Poel (red.) Chris Van de Poel is coördinator van de opleiding literair vertalen i.s.m. het Expertisecentrum Literair Vertalen aan de -

Myth, the Marvelous, the Exotic, and the Hero in the Roman D'alexandre

Myth, the Marvelous, the Exotic, and the Hero in the Roman d’Alexandre Paul Henri Rogers A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages (French) Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: Dr. Edward D. Montgomery Dr. Frank A. Domínguez Dr. Edward D. Kennedy Dr. Hassan Melehy Dr. Monica P. Rector © 2008 Paul Henri Rogers ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract Paul Henri Rogers Myth, the Marvelous, the Exotic, and the Hero in the Roman d’Alexandre Under the direction of Dr. Edward D. Montgomery In the Roman d’Alexandre , Alexandre de Paris generates new myth by depicting Alexander the Great as willfully seeking to inscribe himself and his deeds within the extant mythical tradition, and as deliberately rivaling the divine authority. The contemporary literary tradition based on Quintus Curtius’s Gesta Alexandri Magni of which Alexandre de Paris may have been aware eliminates many of the marvelous episodes of the king’s life but focuses instead on Alexander’s conquests and drive to compete with the gods’ accomplishments. The depiction of his premature death within this work and the Roman raises the question of whether or not an individual can actively seek deification. Heroic figures are at the origin of divinity and myth, and the Roman d’Alexandre portrays Alexander as an essentially very human character who is nevertheless dispossessed of the powerful attributes normally associated with heroic protagonists. -

Alles Verandert Altijd P Erspectieven Op Literair Vertalen

verandert altijd verandert Alles Kaikki Vše Alles verandert altijd is een onmisbaar instrument voor de literair vertaler in opleiding en de beginnende en gevorderde professional bij het vertalen in en uit het Nederlands. Voor het eerst worden Everything hier alle belangrijke aspecten van het literair vertalen helder en bevattelijk samengebracht: de zakelijke en financiële aspecten, de basiskennis en vaardigheden die deze activiteit veronderstelt, vertalen op literair Perspectieven Tutto de algemene kernbegrippen en uitdagingen, het vertalen van de traditionele literaire genres, maar ook van kinder- en jeugd- literatuur, literaire non-fictie en filosofie, en de ‘nazorg’ in de vorm Alles van revisie, marketing en promotie. Het boek is een initiatief van het Expertisecentrum Literair verandert altijd Vertalen (ELV), en bevat bijdragen van 23 vertaalexperts (weten- schappers, opleiders en vertalers), onder eind redactie van Lieven D’hulst en Chris Van de Poel. Beiden zijn lid van het wetenschap- Perspectieven pelijk comité van het ELV, een partnerschap van de Taalunie, de KU Leuven en de Universiteit Utrecht, in samenwerking met het (red.) de Poel en Chris Van D’hulst Lieven Nederlands Letterenfonds en het Vlaams Fonds voor de Letteren. op literair vertalen Lieven D’hulst is gewoon hoogleraar Franstalige letter kunde en vertaalwetenschap aan de Letterenfaculteit van de KU Leuven. Lieven D’hulst en Chris Van de Poel (red.) Chris Van de Poel is coördinator van de opleiding literair vertalen i.s.m. het Expertisecentrum Literair Vertalen aan de -

Aeschylus and O'neill: a Study in Tragedy

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Senior Scholar Papers Student Research 1958 Aeschylus and O'Neill: a study in tragedy Philippa Blume Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/seniorscholars Colby College theses are protected by copyright. They may be viewed or downloaded from this site for the purposes of research and scholarship. Reproduction or distribution for commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the author. Recommended Citation Blume, Philippa, "Aeschylus and O'Neill: a study in tragedy" (1958). Senior Scholar Papers. Paper 30. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/seniorscholars/30 This Senior Scholars Paper (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Scholar Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. A: : RCV=:J BY INTRODUCTION:..................................... i PtLttT I: GRf~E.K 'I'RA:J2DY Introduc ti on ••••••••••••• , .......... • " A. Plot Hnd 'I'heme •••• J •• .......... • • • 2 3. Ideas on the Universe and Gods. • • • 11 C. Ideas on Man ••••• ............. 15 D. The Nature of the Trl-lE:ic Hero. • • • • 29 PART II: """' Oili,S'I'BIA end HCURNING BECCMES ELECTRA Introduction. • .... .. • • • • • -'"" ! A. 3tructur8 • .• • • ... • • • • • c,.,' c:" ;3. CharF-cterizat1on. • • • • • • • • • • • • 1-,-9 C. .-rrlel'le ani Imager-y • • • • 9L: CC~·;CLU.:'IC:': ••••••••.••••••••••••.•••••••.••••••••••112 ?CCT::;CT2S to :::',:.R:' -

V7 Redux.Pdf

VERDAD (PEDRO DE LA)fseNA. --- peed The interpretation of the Harwich dream ... Lond., 1709. E.B.P .2845 Acc. Ver. VERDAGNER (JACINTO). - See MONTOLIU (MANUEL DE). Les grans personalitats de la literatura catalana. Vol. 8. La Renaixenga i els Jocs Florals. V. VERDAM (JAKOB). Middelnederlandsch handwoordenboek. Bewerkt door J.V. Ouveranderde herdruk en van het woord 'sterne r of o pnieuw bewerkt door C.H.E. Wubben. ts-Gravenhage, 1949• Ref. .4 Dut. Uit de geschiedenis der nederlandsche taal. 4e druk. Herzien door F.A. Stoett. Zutphen, 1923- •4393 Ver. See VERWIJS (E.) and V. (#13ft*. VERBANDI. Utgefendur: B.E.6. Torleifsson, E. Hjorleifsson, G. Palsson ... Kaupmannahofn, 1882. LL.104.7.2. Blondal Collection. VERDAVAINE (GEORGES). --- Pictures of ruined Belgium. Visions de la Belgique detruite. Seventy-two pen and ink sketches drawn on the spot by L. Berden. The French text by G.V., founded on the official reports. The translation by J.L. May. 2nd ed. Lond., 1917. Ah.1.17. VERDCOURT (BERNARD. --- and TRUMP (E.C.). --- Common poisonous plants of East Africa. Lond. [1969.] C Lib. ADDITIONS VERDAM (JAKOB). --- Uit de geschiedenis der nederlandsche taal. 2de, geheel omgewerkte, uitgave. Dordrecht, 1902. .4393 Ver. VERDE (CESARIO). --- 0 livro de Cesario Verde. Introduqao por M.E.T. Ferreira. [Bibl. Ulisseia de Aut. Port. 2.] [Lisbon,1981?] .86913 Ver. --- Antologia comentada de^poesias de "0 livro de Cesario Verde'. Realizacao didactica de L.A. de Oliveira. Com sinteses criticas ... [Porto] 1980. .86913 Ver. VERDEAUX (GEORGES). --- See DELAY (JEAN) and V. (G.) VERDEGUER (FEDERICO SUAREZ). See SUAREZ VERDEGUER (FEDERICO). VERDEIL (AUGUSTUS). --- Diss. -

Rewriting Dante: the Creation of an Author from the Middle Ages to Modernity

Rewriting Dante: The Creation of an Author from the Middle Ages to Modernity by Laura Banella Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date: _______________ Approved: ___________________________ Martin G. Eisner, Supervisor ___________________________ David F. Bell, III ___________________________ Roberto Dainotto ___________________________ Valeria Finucci Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT Rewriting Dante: The Creation of an Author from the Middle Ages to Modernity by Laura Banella Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date: _________________ Approved: ___________________________ Martin G. Eisner, Supervisor ___________________________ David F. Bell, III ___________________________ Roberto Dainotto ___________________________ Valeria Finucci An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Laura Banella 2018 Abstract Rewriting Dante explores Dante’s reception and the construction of his figure as an author in early lyric anthologies and modern editions. While Dante’s reception and his transformation into a cultural authority have traditionally been investigated from the point of view of the Commedia, I argue that these lyric anthologies provide a new perspective for understanding how the physical act of rewriting Dante’s poems in various combinations and with other texts has shaped what I call after Foucault the Dante function” and consecrated Dante as an author from the Middle Ages to Modernity. The study of these lyric anthologies widens our understanding of the process of Dante’s canonization as an author and, thus, as an authority (auctor & auctoritas), advancing our awareness of authors both as entities that generate power and that are generated by power. -

Singing in Unknown Languages: a Small Exercise in Applied Translation Theory Brian Mossop, York University School of Translation, Toronto

The Journal of Specialised Translation Issue 20 – July 2013 Singing in Unknown Languages: a small exercise in applied translation theory Brian Mossop, York University School of Translation, Toronto ABSTRACT When choirs sing in languages unknown to most of their members, they are faced with the questions: what do these words mean, and how do I pronounce them? Translation theory can help provide practical phonetic and semantic aids to choir members. Catford’s notions of phonological translation and transliteration are extended to solve the phonetic problem. The semantic problem is solved by writing multiple translations into the singers’ scores. KEYWORDS Choral music, phonetics, spelling, transliteration, meaning levels, applied theory. 1. Phonetics and semantics in choral music In the English-speaking world, choral singing is an extremely popular pastime and, interestingly, amateur choirs often sing works in languages which most members of the choir do not know. The question thus arises: What role does translation play and what role could it play as a choir rehearses and performs works in unfamiliar languages? This is a question which, as far as I know, has never been addressed in the literature on music and translation. Most of that literature is concerned with translations which will themselves be sung—not with aids to singing in the original language of a work. The remainder of the literature is about opera surtitles, which are aids for the audience, not the singers. To begin, a few words about musical communication. Speech communicates by relating sound to conventional linguistic meanings (semantics), but music communicates directly through sound. This is obvious with instrumental music, but choral music is no different. -

The Aesthetics of Classical Reception in 20 Century American

Strange New Canons: The Aesthetics of Classical Reception in 20th Century American Experimental Poetics by Matthew S. Pfaff A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Professor Yopie Prins, Chair Professor Sara Ahbel-Rappe Associate Professor Basil Dufallo Associate Professor Joshua L. Miller Assistant Professor Gillian White 2 © Matthew S. Pfaff ii for Carla— ἀντι τᾶσ ἔγω οὐδὲ Λυδίαν παῖσαν οὐδ᾽ ἔρανναν. iii Contents Dedication ii. List of Figures iv. Introduction: Literary Canonicity And Poetic Innovation 1 Rethinking Reception Aesthetics: Methods and New Models 16 Overview Of Chapters 28 1. Translating Opacity: Homophony and the Material Text 33 “Askforaclassic, Inc.”: The Classics And The Culture Industry 38 “pulchertime” or “Poe tit”: David Melnick’s Poetics Of Epic Farce 63 2. Residual Mainstream Margins: New American Classicisms 82 The Invention of “HUMANITY”: Allen Ginsberg’s Mainstream Margins 92 “A title not chosen for dancing”: Jack Spicer’s Residual Margins 113 3. C=L=A=S=S=I=C=I=S=M=S and Beyond 129 A Critique of Pure Skepticism: Susan Howe’s Luminous Shards 137 A Critique of Pure Citation: Charles Bernstein and the Sublime Object of Bibliography 155 Conclusion: Strange New Classical Reception Studies 174 Works Cited 192 iv List of Figures 1.1: Front cover of David Melnick’s Eclogs 72 3.1: Untitled poem (“Eudoxus”) from Charles Bernstein’s The Sophist 159 3.2: Electronic text, “Littoral,” Charles Bernstein 162 4.1: Front cover and side-view of Anne Carson’s Nox 176 4.2: Clipping of Catullus 101 in Nox 178 4.3: “Snub-Poemed,” Johannes Sigil 181 1 Introduction: Literary Canonicity and Poetic Innovation The writer who shuns the deceptive aspects of tradition and assumes it no longer has anything to do with him still is constrained by it, above all through language. -

Experience St

ANNUAL DONOR REPORT 2007-08 THE ST. FRANCIS COLLEGE EXPERIENCE ST. FRANCIS COLLEGE 2007–08 ANNUAL DONOR REPORT Experience 2 4 6 8 Executive Academics Students Alumni Messages A letter from The St. Francis College Students thrive in an A lifelong relationship Brendan J. Dugan ’68, experience begins in environment that with St. Francis College president, and the classroom. New combines challenging contributes to a message from technologies and academics, satisfying alumni John F. Tully ’67, program innovations extracurricular experience. Lending chairman of the board are attracting high- activities, great expertise, mentoring of trustees, offer quality faculty to the internships and study students and raising reasons for optimism College. abroad programs. funds are just some of at St. Francis College the ways alumni stay now and in the future. connected. St. Francis College Donor Report “When we attend events such as the Scholarship “Because of the quality of our faculty and Reception, it’s striking to see the wonderful technology resources, St. Francis College relationships at St. Francis College among Management and Information Technology students, faculty and alumni.” majors are at the top of their game.” — Elizabeth Becker ’78 — Dr. Timothy J. Houlihan academic dean and vice president for Academic Affairs St. Francis 10 12 36 37 Institutional Honor Roll of Statement of 2007–08 Advancement Donors Activities St. Francis College Board Continuous We acknowledge Details provide an of Trustees and improvement is those who contributed overview of the possible through the generously to financial health of Alumni Board generosity of alumni St. Francis College St. Francis College. of Directors and friends. -

The Perverse Library

the perverse library The Perverse Library CRAIG DWORKIN the perverse library Craig Dworkin Published 2010 by information as material York, England information as material publishes work by artists and writers who use extant material — selecting it and re-framing it to generate new meanings — and who, in doing so, disrupt the existing order of things. www.informationasmaterial.com ISBN 978-1-907468-03-2 Cover image Étienne-Louis Boullée Deuxieme projet pour la Bibliothèque du Roi, 1785 Typography Groundwork, Skipton, England Printed in Great Britain by Henry Ling, The Dorset Press, Dorchester Contents Pinacographic Space . 9 The Perverse Library . 45 A Perverse Library . 53 Pinacographic Space The library is its own discourse. You listen in, don’t you? — Thomas Nakell, The Library of Thomas Rivka 9 ne night, a friend — a poet who had been one of the Ocentral fi gures in Language Poetry — noticed me admir- ing his collection of books, which lined his entire apartment, fl oor to ceiling. Political theory crowded the entryway; music and design pushed up against the dining room; in the living room he seemed to have a complete collection of publications from his fellow travelers: the most thorough document of post-war American avant-garde poetry imaginable. I noticed, one after another, books of which I had only heard mention but had never before seen. At the top of one shelf I thought I caught a glimpse of Robert Grenier’s infamous “chinese box”- bound set of cards, Sentences. I tried to express my admiration by saying something about the especially choice inclusions, mentioning a couple of particularly obscure volumes to let him know that it wasn’t just an off-hand compliment, or a statement about the sheer number of books, and that I had really read the shelves carefully and knew just how impres- sively replete the collection was. -

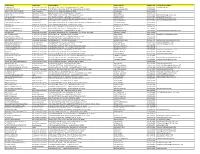

Report of Contracting Activity

Vendor Name Vendor Type Vendor Address Vendor Contact Vendor Phone Vendor E-Mail Address 100REPORTERS Professional Corporation 910 17TH ST. NW SUITE 215 WASHINGTON,DC US 20006 DIANA SCHEMO 202-683-6485 [email protected] 1164 BLADENSBURG LLC Professional Corporation 3232 GEORGIA AVENUE NW SUITE 100 WASHINGTON,DC US 20010 ADRIAN WASHINGTON 202-722-6002 1213 U STREET LLC /T/A BEN'S State Corporation 1213 U ST., NW WASHINGTON,DC US 20009 VIRGINIA ALI 202-667-0909 19TH STREET BAPTIST CHRUCH Government Entity 4606 16TH STREET, NW WASHINGTON,DC US 20011 ROBIN SMITH 202-829-2773 1SPATIAL INC. Out of State Corporation 45945 CENTER OAK PLAZA #190 STERLING,VA US 20166 MIKE MATHEWS 703-444-9488 [email protected] 1ST CDL TRAINING CTR OF NOVA Partnership 5716 TELEGRAPH ROAD ALEXANDRIA,VA US 22303 NADEEM IKRAM 703-347-7999 [email protected] 1ST CHOICE LLC Professional Corporation 1558 BUTLER STREET SE APARTMENT 201 WASHINGTON,DC US 20020 VICTOR BATTLE 202-459-1017 [email protected] 1ST NEEDS MEDICAL Sole Ownership 1411 H STREET N.E. WASHINGTON,DC US 20002 DARIUS JEFFERSON 844-417-8633 [email protected] 21ST CENTURY SECURITY, LLC Sole Ownership 1550 CATON CENTER DRIVE, #A DBA/PROSHRED SECURITY BALTIMORE,MD US 21227 C. MARTIN FISHER 410-242-9224 2228 MLK LLC Professional Corporation 11701 BOWMAN GREEN DRIVE RESTON,VA US 20190 TIMOTHY M. CHAPMAN 703-581-6111 2255 MLK LLC Professional Corporation 1805 7th Street NW 8th Floor Washington,DC US 20001 Stan Voudrie 703-606-2971 3534 EAST CAP VENTURE LLC Professional Corporation 3050 K STREET NW SUITE 125 WASHINGTON,DC US 20007 M. -

Gnomes of the Oresteia: Lyrical Reflection and Its Dramatic Relevance

GNOMES OF THE ORESTEIA: LYRICAL REFLECTION AND ITS DRAMATIC RELEVANCE By Craig Richard Cooper B.A., The University of Alberta A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Classics We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October 1985 ,© Craig Richard Cooper, 1985 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date Oct.// '??r DE-6(3/81) ABSTRACT One of the most distinctive features of Aeschylus' poetic style is the choral odes. The odes can generally be divided into two parts: lyrical narrative and lyrical reflection. The narrative sections motivate the main action of the drama, often relating past events and causes. The lyrical reflection is distinguished from the narrative parts by its overt moralizing that lift the dramatic action from the particular to the universal. Within these sections of the ode, are clusters of moral generalizations or gnomes, dealing with a variety of topics but always of a distinctively moral nature.