Amazon.Com: Marching Towards Profitability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liquid Audio, Inc. LQID 56 $ 25 -$ 48.4

Tornado Report, December 31, 2002 Patrick Lannigan - Lannigan and Associates - 905-305-8004 [email protected] Tornado Report. All prices as of market close Tuesday, December 31, 2002 Figures do not account for debt, which is usually not a concern for all but the very largest software and hardware companies (e.g. Lucent, Nortel, IBM, CA, etc.) Cash (as it is tallied here) = Cash + Securities. ( Warning: Cash + Securities data can lag earnings data - by many weeks!) MC = Market Capitalization ttm = Trailing Twelve Months Companies are in order of --> TR = Tornado Ratio = (MC - CASH) / Revenue For more information on the TR (Tornado Ratio) go to: http://www.lannigan.org/tornado_report.htm Company Symbol MC MC-Cash MC/Rev. TR Cash Rev. EPS P/E Price Shares (mill.) (mill) (ttm) (mill.) (ttm) (ttm) (mill.) Liquid Audio, Inc. LQID$ 56 -$ 25 48.4 -21.81$ 81 $ 1 -$0.75 n/a$ 2.5 22.8 Clarus CLRS$ 88 -$ 15 22.4 -3.68$ 103 $ 4 -$1.09 n/a$ 5.6 15.7 BackWeb Technologies Ltd. BWEB$ 9 -$ 19 1.0 -2.03$ 28 $ 9 -$0.73 n/a$ 0.2 39.8 Blue Martini Software BLUE$ 30 -$ 41 0.9 -1.23$ 71 $ 34 -$5.75 n/a$ 2.9 10.4 FirePond, Inc. FIRE$ 9 -$ 20 0.4 -0.93$ 29 $ 22 -$5.38 n/a$ 2.5 3.7 Keynote KEYN$ 220 -$ 19 5.8 -0.51$ 239 $ 38 -$2.23 n/a$ 7.7 28.5 Commerce One CMRC$ 80 -$ 68 0.6 -0.48$ 148 $ 142 -$17.61 n/a$ 2.8 29.2 Centra Software CTRA$ 26 -$ 14 0.7 -0.40$ 40 $ 35 -$0.64 n/a$ 1.0 26.0 Liberate Technologies LBRT$ 122 -$ 27 1.7 -0.37$ 149 $ 73 -$2.70 n/a$ 1.1 107.6 Rogue Wave Software RWAV$ 18 -$ 10 0.4 -0.23$ 28 $ 43 -$0.68 n/a$ 1.8 10.2 Pivotal Corporation PVTL$ 18 -$ 12 0.3 -0.19$ 30 $ 66 -$3.42 n/a$ 0.7 25.3 Vignette Corporation VIGN$ 306 -$ 29 1.8 -0.18$ 335 $ 167 -$4.33 n/a$ 1.2 250.6 Docent DCNT$ 41 -$ 4 1.5 -0.14$ 45 $ 28 -$2.53 n/a$ 2.9 14.3 Safeguard Scientifics SFE$ 162 -$ 164 0.1 -0.10$ 326 $ 1,650 -$1.37 n/a$ 1.4 119.4 Selectica, Inc. -

Amazon.Com, Inc. Securities Litigation 01-CV-00358-Consolidated

Case 2:01-cv-00358-RSL Document 30 Filed 10/05/01 Page 1 of 215 1 THE HONORABLE ROBERT S. LASNIK 2 3 4 5 6 vi 7 øA1.S Al OUT 8 9 UNITE STAThS15iSTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF WASHINGTON 10 AT SEATTLE 11 MAXiNE MARCUS, et al., On Behalf of Master File No. C-01-0358-L Themselves and All Others Similarly Situated, CLASS ACTION 12 Plaintiffs, CONSOLIDATED COMPLAINT FOR 13 VS. VIOLATION OF THE SECURITIES 14 EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 AMAZON COM, INC., JEFFREY P. BEZOS, 15 WARREN C. JENSON, JOSEPH GALLI, JR., THOMAS A. ALBERG, L. JOHN DOERR, 16 MARK J BRITTO, JOEL R. SPIEGEL, SCOTT D. COOK, JOY D. COVEY, 17 'RICHARD L. DALZELL, JOHN D. RISHER, KAVITARK R. SHRIRAM, PATRICIA Q. 18 STONESIFER, JIMMY WRIGHT, ICELYN J. BRANNON, MARY E. ENGSTROM, 19 KLEJNER PERKINS CAUF1ELD & BYERS, MORGAN STANLEY DEAN WITTER, 20 CREDIT SUISSE FIRST BOSTON, MARY MEEKER, JAMIE KIGGEN and USE BUYER, 21 Defendants. 22 In re AMAZON.COM, INC. SECURITIES 23 LITIGATION 24 This Document Relates To: 25 ALL ACTIONS 26 11111111 II 1111111111 11111 III III liii 1111111111111 111111 Milberg Weiss Bershad Hynes & Le955 600 West Broadway, Suite 18 0 111111 11111 11111 liii III III 11111 11111111 San Diego, CA 92191 CV 01-00358 #00000030 TeIephone 619/231-058 Fax: 619/2j.23 Case 2:01-cv-00358-RSL Document 30 Filed 10/05/01 Page 2 of 215 TA L TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Page 3 4 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW I 5 JURISDICTION AND VENUE .............................36 6 THE PARTIES ........................... -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9.405,753 B2 Eyalet Al

US009.405753B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9.405,753 B2 Eyalet al. (45) Date of Patent: Aug. 2, 2016 (54) DYNAMIC RATINGS-BASED STREAMING (56) References Cited MEDIA PLAYBACK SYSTEM U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS Applicant: George Aposporos, Rockville, MD (US) (71) 4,739,567 A 4, 1988 Cardin 4,788,675 A 11/1988 Jones et al. (72) Inventors: Aviv Eyal, New York, NY (US); George 4,870,579 A 9/1989 Hey Aposporos, Rockville, MD (US) 4,996,642 A 2/1991 Hey (73) Assignee: George Aposporos, Rockville, MD (US) (Continued) (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS patent is extended or adjusted under 35 EP O649 121 A2 4f1995 U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. EP O649 121 A3 8, 1995 (21) Appl. No.: 14/935,780 (Continued) (22) Filed: Nov. 9, 2015 OTHER PUBLICATIONS (65) Prior Publication Data U.S. Appl. No. 09/696,333, filed Oct. 24, 2000, Eyalet al. US 2016/OO63OO2A1 Mar. 3, 2016 (Continued) Related U.S. Application Data Primary Examiner — Krisna Lim (63) Continuation of application No. 14/327,789, filed on (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm — Jason H. Vick; Sheridan Jul. 10, 2014, which is a continuation of application Ross, PC No. 13/355,867, filed on Jan. 23, 2012, now Pat. No. 8.782,194, which is a continuation of application No. (57) ABSTRACT (Continued) A method is provided for playing back media from a network. (51) Int. C. The method includes receiving a search criteria from a net G06F 15/16 (2006.01) work enabled device. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 13F Form 13F COVER PAGE Report for the Calendar Year or Quarter Ended: March 31, 2000 Check here if Amendment [ ]; Amendment Number: _______________ This Amendment (Check only one): [ ] is a restatement [ ] adds new holdings entries. Institutional Investment Manager Filing this Report: Intel Corporation 2200 Mission College Boulevard Santa Clara, CA 95052-8119 Form 13F File Number: 28-5160 Person Signing this Report on Behalf of Reporting Manager: Arvind Sodhani, Vice President and Treasurer (408) 765-1240 --------------------------------------------------------------- ATTENTION--Intentional misstatements or omissions of facts constitute Federal Criminal Violations. See 18 U.S.C. 1001 and 15 U.S.C. 78ff(a) --------------------------------------------------------------- The institutional investment manager filing this report and the person by whom it is signed hereby represent that the person signing the report is authorized to submit it, that all information contained herein is true, correct and complete, and that it is understood that all required items, statements, schedules, lists, and tables, are considered integral parts of this form. Signature, Place and Date of Signing: /s/Arvind Sodhani Santa Clara, California May 11, 2000 - ------------------- Report Type (Check only one): [X] 13F HOLDINGS REPORT. (Check here if all holdings of this reporting manager are reported in this report.) [ ] 13F NOTICE. (Check here if no holdings reported are in this report, -

Mp3

<d.w.o> mp3 book: Table of Contents <david.weekly.org> January 4 2002 mp3 book Table of Contents Table of Contents auf deutsch en español {en français} Chapter 0: Introduction <d.w.o> ● What's In This Book about ● Who This Book Is For ● How To Read This Book books Chapter 1: The Hype code codecs ● What Is Internet Audio and Why Do People Use It? mp3 book ● Some Thoughts on the New Economy ● A Brief History of Internet Audio news ❍ Bell Labs, 1957 - Computer Music Is Born pictures ❍ Compression in Movies & Radio - MP3 is Invented! poems ❍ The Net Circa 1996: RealAudio, MIDI, and .AU projects ● The MP3 Explosion updates ❍ 1996 - The Release ❍ 1997 - The Early Adopters writings ❍ 1998 - The Explosion video ❍ sidebar - The MP3 Summit get my updates ❍ 1999 - Commercial Acceptance ● Why Did It Happen? ❍ Hardware ❍ Open Source -> Free, Convenient Software ❍ Standards ❍ Memes: Idea Viruses ● Conclusion page source http://david.weekly.org/mp3book/toc.php3 (1 of 6) [1/4/2002 10:53:06 AM] <d.w.o> mp3 book: Table of Contents Chapter 2: The Guts of Music Technology ● Digital Audio Basics ● Understanding Fourier ● The Biology of Hearing ● Psychoacoustic Masking ❍ Normal Masking ❍ Tone Masking ❍ Noise Masking ● Critical Bands and Prioritization ● Fixed-Point Quantization ● Conclusion Chapter 3: Modern Audio Codecs ● MPEG Evolves ❍ MP2 ❍ MP3 ❍ AAC / MPEG-4 ● Other Internet Audio Codecs ❍ AC-3 / Dolbynet ❍ RealAudio G2 ❍ VQF ❍ QDesign Music Codec 2 ❍ EPAC ● Summary Chapter 4: The New Pipeline: The New Way To Produce, Distribute, and Listen to Music ● Digital -

DIRTY LITTLE SECRETS of the RECORD BUSINESS

DIRTY BUSINESS/MUSIC DIRTY $24.95 (CAN $33.95) “An accurate and well-researched exposé of the surreptitious, undisclosed, W hat happened to the record business? and covert activities of the music industry. Hank Bordowitz spares no It used to be wildly successful, selling LI one while exposing every aspect of the business.” LI outstanding music that showcased the T producer of Talking Heads, T performer’s creativity and individuality. TLE SE —Tony Bongiovi, TLE Aerosmith, and the Ramones Now it’s in rapid decline, and the best music lies buried under the swill. “This is the book that any one of us who once did time in the music SE business for more than fifteen minutes and are now out of the life wish This unprecedented book answers this CR we had written. We who lie awake at nights mentally washing our hands CR question with a detailed examination LITTLE of how the record business fouled its as assiduously yet with as much success as Lady Macbeth have a voice DIRTYLITTLE ET DIRTY in Hank Bordowitz. Now I have a big book that I can throw at the ET own livelihood—through shortsighted- S liars, the cheats, and the bastards who have fooled me twice.” S ness, stubbornness, power plays, sloth, and outright greed. Dirty Little Secrets o —Hugo Burnham, drummer for Gang of Four, o f of the Record Business takes you on a former manager and major-label A&R executive f the the hard-headed tour through the corridors ofof thethe of the major labels and rides the waves “Nobody should ever even think about signing any kind of music industry SECRSECRETSETS contract without reading this book. -

Online Entertainment and Copyright Law: Coming Soon to a Digital Device Near You Hearing

S. HRG. 107–283 ONLINE ENTERTAINMENT AND COPYRIGHT LAW: COMING SOON TO A DIGITAL DEVICE NEAR YOU HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 3, 2001 Serial No. J–107–9 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 77–094 txt WASHINGTON : 2002 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah, Chairman STROM THURMOND, South Carolina PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware JON KYL, Arizona HERBERT KOHL, Wisconsin MIKE DEWINE, Ohio DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois MARIA CANTWELL, Washington SHARON PROST, Chief Counsel MAKAN DELRAHIM, Staff Director BRUCE COHEN, Minority Chief Counsel and Staff Director (II) C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS OF COMMITTEE MEMBERS Page Cantwell, Hon. Maria, a U.S. Senator from the State of Washington ................ 170 Hatch, Hon. Orrin G., a U.S. Senator from the State of Utah ............................ 1 Leahy, Hon. Patrick J., a U.S. Senator from the State of Vermont .................... 3 WITNESSES Barry, Hank, Interim Chief Executive Officer, Napster ...................................... 22 Berry, Ken, President and Chief Executive Officer, EMI Recorded Music ......... 51 Cannon, Hon. -

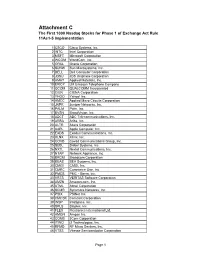

Attachment C the First 1000 Nasdaq Stocks for Phase 1 of Exchange Act Rule 11Ac1-5 Implementation

Attachment C The First 1000 Nasdaq Stocks for Phase 1 of Exchange Act Rule 11Ac1-5 Implementation 1 CSCO Cisco Systems, Inc. 2 INTC Intel Corporation 3 MSFT Microsoft Corporation 4 WCOM WorldCom, Inc. 5 ORCL Oracle Corporation 6 SUNW Sun Microsystems, Inc. 7 DELL Dell Computer Corporation 8 JDSU JDS Uniphase Corporation 9 AMAT Applied Materials, Inc. 10 ERICY LM Ericsson Telephone Company 11 QCOM QUALCOMM Incorporated 12 CIEN CIENA Corporation 13 YHOO Yahoo! Inc. 14 AMCC Applied Micro Circuits Corporation 15 JNPR Juniper Networks, Inc. 16 PALM Palm, Inc. 17 BVSN BroadVision, Inc. 18 ADCT ADC Telecommunications, Inc. 19 ARBA Ariba, Inc. 20 ALTR Altera Corporation 21 AAPL Apple Computer, Inc. 22 EXDS Exodus Communications, Inc. 23 XLNX Xilinx, Inc. 24 COVD Covad Communications Group, Inc. 25 SEBL Siebel Systems, Inc. 26 NXTL Nextel Communications, Inc. 27 NTAP Network Appliance, Inc. 28 BRCM Broadcom Corporation 29 BEAS BEA Systems, Inc. 30 CMGI CMGI, Inc. 31 CMRC Commerce One, Inc. 32 PMCS PMC - Sierra, Inc. 33 VRTS VERITAS Software Corporation 34 AMZN Amazon.com, Inc. 35 ATML Atmel Corporation 36 SCMR Sycamore Networks, Inc. 37 PSIX PSINet Inc. 38 CMCSK Comcast Corporation 39 INSP InfoSpace, Inc. 40 SPLS Staples, Inc. 41 FLEX Flextronics International Ltd. 42 AMGN Amgen Inc. 43 COMS 3Com Corporation 44 ITWO i2 Technologies, Inc. 45 RFMD RF Micro Devices, Inc. 46 VTSS Vitesse Semiconductor Corporation Page 1 47 INKT Inktomi Corporation 48 EXTR Extreme Networks, Inc. 49 SDLI SDL, Inc. 50 MFNX Metromedia Fiber Network, Inc. 51 VRSN VeriSign, Inc. 52 IMNX Immunex Corporation 53 COST Costco Wholesale Corporation 54 KLAC KLA-Tencor Corporation 55 TRLY Terra Networks, S.A. -

The Music Industry in the 21St Century Facing the Digital Challenge

Source: REPORTS PORTAL Pricing and ordering | Visit the Screen Digest REPORTS portal |Send us an email The Music Industry in the 21st Century Facing the digital challenge Jürgen Preiser and Armin Vogel ma non troppo" This sample is for evaluation purposes only: unauthorised use or distribution is forbidden *" REPORT EXTRACT: FULL VERSION IS 236 PAGES WITH OVER 200 CHARTS AND TABLES screendigest Pricing and ordering | Visit the Screen Digest REPORTS portal |Send us an email Source: REPORTS PORTAL Pricing and ordering | Visit the Screen Digest REPORTS portal |Send us an email The music industry in the 21st century The music industry in the 21st century: Facing the digital challenge screendigest Published May 2002 by Screen Digest Limited Screen Digest Limited Lymehouse Studios 38 Georgiana Street London NW1 0EB telephone +44/20 7424 2820 fax +44/20 7580 0060 e-mail [email protected] website www.screendigest.com Authors Jürgen Preiser, Armin Vogel Jürgen Preiser has 15 years’ experience in Editorial Mark Smith music and film entertainment sectors with the Editorial/design David Fisher major multi-media companies Time Warner, Polygram and Universal. He has held national and international positions with these companies as Director Business Development, Director Strategic Planning and Director Market Research. Over the past seven years he worked on various international projects, particularly in new media. More recently, as Venture Director, Media at venture capitalist Venturepark Incuba- tor he was responsible for advising portfolio companies on their strategy and its implementa- tion, directing deal evaluation, and performing due diligence. Armin Vogel is co-founder and managing director of the independent e-business consulting and business development firm Tivona Partners. -

Lighthouse'99 Case Studies Rockin' the Music Business

Lighthouse‘99 Case Studies MP3 Rockin’ the music business “Why, when you can get EBC scorecard music for free, would anyone E-business community type ● Alliance pay for it?” — Steve Marks, Deputy General Context providers ● MP3.com, Listen.com, E-music, RioPort.com Counsel, Recording Industry Association of America Customers ● Music listeners Content providers ● Music labels, artists, users “Our strategy is going to be Commerce service providers ● MP3.com (Digital Audio Music), CyberCash, to make it easier to buy the Anacom Merchant Services, DigiSign music than to steal it.” Infrastructure providers ● Hardware:Saehan — MPMan, Thompson — Gene Hoffman, President and Electronics — the Lyra, Diamond Multimedia CEO, Emusic — the Rio ● “Digital distribution is the Software:Nullsoft — WinAmp, MusicMatch — MusicMatch Jukebox, RealNetworks — future, and we’ve got to get on RealJukebox, Microsoft — Media Player top of it because it’s not wait- ● Telecommunications providers ing for us.” Competitors ● Other digital distribution systems: Liquid — Lars Murray, Director of New Media, Rykodisc Audio, a2b (AT&T), MS Audio ● Traditional distribution media/outlets: compact "The public has the tech- disc, cassette, DVD/radio, MTV, Tower nology before the industry Records, etc. does, and they fear it." Primary value proposition ● Small, digitally compressed music files that can — Chuck D, Public Enemy be transported via the Internet, or stored in any digital device/media "If history has taught us Key technologies and ● MPEG – Level 3 audio compression algorithm, applications software players, “rippers,” encoders, various anything, it's that open plug-ins, PCs, portable hardware devices, always wins. An open com- removable flash memory pression technique will win — Governance structure ● Non-hierarchical. -

Argent Classic Convertible Arbitrage Fund LP, Et Al. V. Amazon.Com, Inc

Case 2:01-cv-00640-RSL Document 52 Filed 04/08/2002 Page 1 of 127 THE HON RABLE ROBERT S LAI 1 4f 1 1. 2 3 -^_ D - ENTERED __ 4 LODGED---^RECEIVED 5 APR 0 8 2002 MR 6 il11l 1111 IN w ^D157UA TSD^D"STRICT`^ RILT OF WASHINGTON CV 01- 00640 900000052 7 DEPUTY 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 WESTERN DISTRICT OF WASHINGTON AT SEATTLE 10 11 ARGENT CLASSIC CONVERTIBLE ARBITRAGE FUND, L.P., on behalf of itself 12 all others similarly situated, No C01-0640L 13 Plaintiff, COMPLAINT-CLASS ACTION 14 V. LEAD PLAINTIFF ARGENT 15 CLASSIC CONVERTIBLE 16 AMAZON.COM INC., JEFFREY P. BEZOS, ARBITRAGE FUND, L P.'S FIRST JILL COVEY, TOM A. ALBERG, SCOTT D. AMENDED CLASS ACTION 17 COOK, L JOHN DOERR, AND PATRICIA Q COMPLAINT FOR VIOLATIONS STONESIFER, OF THE SECURITIES ACT OF 1933 18 19 Defendants. JURY DEMAND 20 Lead Plaintiff Argent Classic Convertible Arbitrage Fund, L P. ("Lead Plaintiff' or 21 22 "Plaintiff'), individually and on behalf of all other persons similarly situated, by its undersigned 23 attorneys, for its first amended complaint, alleges as follows upon personal knowledge as to itself 24 and its own acts, and upon information and belief as to all other matters, based upon the 25 investigation made by and through its attorneys, which investigation included, inter alia, a review of 26 the public documents and press releases of Amazon.com, ("Amazon" or the "Company") and 27 Inc. 28 other defendants and the pleadings filed in this Court in other securities actions filed against McKay Chadwell, C LEAD PLAINTIFF' S FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT - CLASS ACT ML I , ii Avenue, Suite -1 01 (COI-0640L) - 1 U le, Washington 981 G \CLIENTSk01337\001\PLEADll{GS\FISTAMENDEDCOMPLAINT .2 PLD DOC ) 800 Fax (206) 23 -2809 Case 2:01-cv-00640-RSL Document 52 Filed 04/08/2002 Page 2 of 127 defendants Lead Plaintiff believes that further substantial evidentiary support will exist for the 2 allegations set forth below after a reasonable opportunity for discovery NATURE OF ACTION 4 1. -

Fall 2009 Prof

Fall 2009 Prof. Oliver Williamson Wins Nobel Prize in Economics Nonprofit Organization CalBusiness US Postage Haas School of Business PAID University of California, Berkeley Admail West 545 Student Services #1900 Berkeley, CA 94720–1900 CalBusiness The Magazine of the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley Business Beyond Borders From Everest to San Francisco, Alumnus Richard Blum Touches Many Lives Plus: New Haas Leading Through Innovation Award Recognizes Prof. Henry Chesbrough, PhD 97 The Magazine of Fall 2009 CalBusiness the Haas School of Business at the University of Contents California, Berkeley Senior Editor Features Richard Kurovsky On the Cover: Editor 8 Business Beyond Borders Ute S. Frey Richard C. Blum, BS 58, MBA 59, has been Managing Editor named the recipient of the Haas School’s Ronna Kelly, BS 92 2009 Lifetime Achievement Award to recognize his accomplishments in the worlds Staff Writers of business and philanthropy. Valerie Gilbert Pamela Tom Contributing Writers Leading Through Innovation Bill Brazell, Laura Counts, 11 Adjunct Professor Henry Chesbrough, PhD 97, Jennie Lay, Cyril Manning, receives the Haas School’s first Leading Bill Snyder, K.C. Swanson Through Innovation Award. Design Cuttriss & Hambleton, Berkeley Your Haas Network in Digital Media 12 Profiles of Three Haas School Alumni in Printer Digital Media and Entertainment Fong & Fong, Sacramento Darrell Rodriguez, MBA 94, LucasArts Photography Danae Ringelmann, MBA 08, IndieGoGo Robert Bean, Abhijit Bhatlekar, David Porter, MBA 00, 8tracks Jim Block, Toni Gauthier, Peg Skorpinski, Peter Stuckings Your Haas Network in CalBusiness is published by the Haas School of Business, 14 Profiles of Three Haas School Alumni in Asia University of California, Linh Do, MBA 04, Worldwide Orphanages Berkeley.