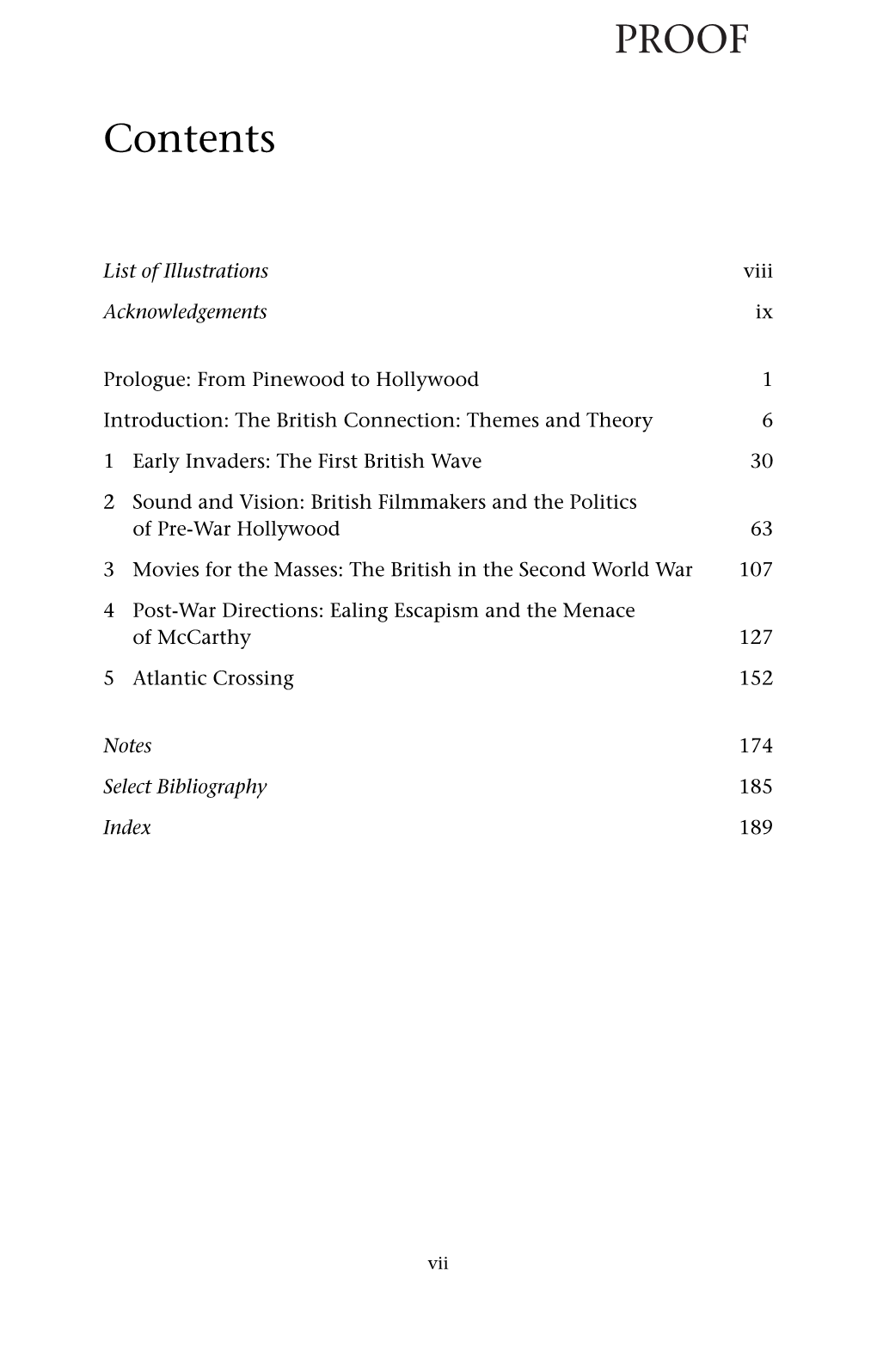

Contents PROOF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inventory of the Joan Fontaine Collection #570

The Inventory of the Joan Fontaine Collection #570 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center TABLE OF CONTENTS Film and Video 1 Audio 3 Printed Material 5 Professional Material 10 Correspondence 13 Financial Material 50 Manuscripts 50 Photographs 51 Personal Memorabilia 65 Scrapbooks 67 Fontaine, Joan #570 Box 1 No Folder I. Film and Video. A. Video cassettes, all VHS format except where noted. In date order. 1. "No More Ladies," 1935; "Tell Me the Truth" [1 tape]. 2. "No More Ladies," 1935; "The Man Who Found Himself," 1937; "Maid's Night Out," 1938; "The Selznick Years," 1969 [1 tape]. 3. "Music for Madam," 1937; "Sky Giant," 1938; "Maid's Night Out," 1938 [1 tape]. 4. "Quality Street," 1937. 5. "A Damsel in Distress," 1937, 2 copies. 6. "The Man Who Found Himself," 1937. 7. "Maid's Night Out," 1938. 8. "The Duke ofWestpoint," 1938. 9. "Gunga Din," 1939, 2 copies. 10. "The Women," 1939, 3 copies [4 tapes; 1 version split over two tapes.] 11. "Rebecca," 1940, 3 copies. 12. "Suspicion," 1941, 4 copies. 13. "This Above All," 1942, 2 copies. 14. "The Constant Nymph," 1943. 15. "Frenchman's Creek," 1944. 16. "Jane Eyre," 1944, 3 copies. 2 Box 1 cont'd. 17. "Ivy," 1947, 2 copies. 18. "You Gotta Stay Happy," 1948. 19. "Kiss the Blood Off of My Hands," 1948. 20. "The Emperor Waltz," 1948. 21. "September Affair," 1950, 3 copies. 22. "Born to be Bad," 1950. 23. "Ivanhoe," 1952, 2 copies. 24. "The Bigamist," 1953, 2 copies. 25. "Decameron Nights," 1952, 2 copies. 26. "Casanova's Big Night," 1954, 2 copies. -

Jim,My Lucas Marjorie Macgregor Michele Morgan Patty Orr Bela Lugosi Frank Mchugh Ralph Morgan William Orr Keye Luke Robert Mcji

Jim,my Lucas Marjorie MacGregor Michele Morgan Patty Orr Bela Lugosi Frank McHugh Ralph Morgan William Orr Keye Luke Robert McJimcy Patricia Morison Orv ilia Lum &Abner Silvia McKay Maro and Yocanella Maureen O'Sullivan Bill Lundigan Fay McKenzie Amarillo Morris Madame Ouspenskaya The Luther Twins Victor McLaglen Chester Morris Lynne Overman Diana Lynn Barton MacLane Ella May Morris Charles Overman Jeffrey Lynn Fred MacMurray Lili Morris Charles Owens Mary Lynn Haven MacQuarrie Zero Mostel Gene Owens Dorothy McQuire Alan Mowbray Jack Owens Eve McVeigh Paul Muni Rita Owin Jeanette MacDonald Martha Mears Ethel Madison Ona Munson Jane Melardy Corinna Mura Marjorie Main P-38's (Dancers) Melody Girls George Murphy Sally Paine Jerry Mann Harry Mendosa Rose Murphy John Pallett Marjorie Manners Adolphe Menjou Senator Murphy Cecilia Parker Martha Manners Johnny Mercer Ken Murray Eleanor Parker Philip Merivale Irene Manning Clarence Muse Hats Parker Virginia Maples Lynn Merrick Music Maids Lou Merrill Jean Parker Adele Mara Carmel Myers Jetsy Parker Frederic March Merry Macs Mary Ellen Myron • Murray Parker Dorie Marie Ray Middleton Odette Myrtil Parkyakarkus Mona Marris Ray Milland Patsy Lee Parsons June Marlowe Ann Miller Anne Nagel Gail1Patrick Nancy Marlowe Miller & Barlow Conrad Nagel Vera Marsh Edwin Miller Richard Paxton Cliff Nasarro John Payne Herbert Marshall Glenn Miller (·Orch.) Nasimova Mary Martin Jimmie Miller Al Pearce Charles Neff Neva Peoples Tony Martin Lorraine Miller Ossie Nelson Barbara Pepper Johnny Marvin Sidney Miller John Nesbit Buddy Pepper Chico Marx Mills Brothers Nicholas Brothers Tommy Perry Groucho Marx Minne & Billy Nicodemus Susan Peters Harpo Marx Carmen Miranda Gertrude Niessen Mrs. -

Pilot Season

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College Spring 2014 Pilot Season Kelly Cousineau Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cousineau, Kelly, "Pilot Season" (2014). University Honors Theses. Paper 43. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.77 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Pilot Season by Kelly Cousineau An undergraduate honorsrequirements thesis submitted for the degree in partial of fulfillment of the Bachelor of Arts in University Honors and Film Thesis Adviser William Tate Portland State University 2014 Abstract In the 1930s, two historical figures pioneered the cinematic movement into color technology and theory: Technicolor CEO Herbert Kalmus and Color Director Natalie Kalmus. Through strict licensing policies and creative branding, the husband-and-wife duo led Technicolor in the aesthetic revolution of colorizing Hollywood. However, Technicolor's enormous success, beginning in 1938 with The Wizard of Oz, followed decades of duress on the company. Studios had been reluctant to adopt color due to its high costs and Natalie's commanding presence on set represented a threat to those within the industry who demanded creative license. The discrimination that Natalie faced, while undoubtedly linked to her gender, was more systemically linked to her symbolic representation of Technicolor itself and its transformation of the industry from one based on black-and-white photography to a highly sanctioned world of color photography. -

The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Film Studies (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-2021 The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Michael Chian Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/film_studies_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chian, Michael. "The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood." Master's thesis, Chapman University, 2021. https://doi.org/10.36837/chapman.000269 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film Studies (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood A Thesis by Michael Chian Chapman University Orange, CA Dodge College of Film and Media Arts Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Film Studies May, 2021 Committee in charge: Emily Carman, Ph.D., Chair Nam Lee, Ph.D. Federico Paccihoni, Ph.D. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Copyright © 2021 by Michael Chian III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my advisor and thesis chair, Dr. Emily Carman, for both overseeing and advising me throughout the development of my thesis. Her guidance helped me to both formulate better arguments and hone my skills as a writer and academic. I would next like to thank my first reader, Dr. Nam Lee, who helped teach me the proper steps in conducting research and recognize areas of my thesis to improve or emphasize. -

The Horror Film Series

Ihe Museum of Modern Art No. 11 jest 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart Saturday, February 6, I965 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE The Museum of Modern Art Film Library will present THE HORROR FILM, a series of 20 films, from February 7 through April, 18. Selected by Arthur L. Mayer, the series is planned as a representative sampling, not a comprehensive survey, of the horror genre. The pictures range from the early German fantasies and legends, THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI (I9I9), NOSFERATU (1922), to the recent Roger Corman-Vincent Price British series of adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe, represented here by THE MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH (I96IO. Milestones of American horror films, the Universal series in the 1950s, include THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (1925), FRANKENSTEIN (1951), his BRIDE (l$55), his SON (1929), and THE MUMMY (1953). The resurgence of the horror film in the 1940s, as seen in a series produced by Val Lewton at RR0, is represented by THE CAT PEOPLE (19^), THE CURSE OF THE CAT PEOPLE (19^4), I WALKED WITH A ZOMBIE (19*£), and THE BODY SNAT0HER (19^5). Richard Griffith, Director of the Film Library, and Mr. Mayer, in their book, The Movies, state that "In true horror films, the archcriminal becomes the archfiend the first and greatest of whom was undoubtedly Lon Chaney. ...The year Lon Chaney died [1951], his director, Tod Browning,filmed DRACULA and therewith launched the full vogue of horror films. What made DRACULA a turning-point was that it did not attempt to explain away its tale of vampirism and supernatural horrors. -

Movie Mirror Book

WHO’S WHO ON THE SCREEN Edited by C h a r l e s D o n a l d F o x AND M i l t o n L. S i l v e r Published by ROSS PUBLISHING CO., I n c . NEW YORK CITY t y v 3. 67 5 5 . ? i S.06 COPYRIGHT 1920 by ROSS PUBLISHING CO., Inc New York A ll rights reserved | o fit & Vi HA -■ y.t* 2iOi5^ aiblsa TO e host of motion picture “fans” the world ovi a prince among whom is Oswald Swinney Low sley, M. D. this volume is dedicated with high appreciation of their support of the world’s most popular amusement INTRODUCTION N compiling and editing this volume the editors did so feeling that their work would answer a popular demand. I Interest in biographies of stars of the screen has al ways been at high pitch, so, in offering these concise his tories the thought aimed at by the editors was not literary achievement, but only a desire to present to the Motion Picture Enthusiast a short but interesting resume of the careers of the screen’s most popular players, rather than a detailed story. It is the editors’ earnest hope that this volume, which is a forerunner of a series of motion picture publications, meets with the approval of the Motion Picture “ Fan” to whom it is dedicated. THE EDITORS “ The Maples” Greenwich, Conn., April, 1920. whole world is scene of PARAMOUNT ! PICTURES W ho's Who on the Screcti THE WHOLE WORLD IS SCENE OF PARAMOUNT PICTURES With motion picture productions becoming more masterful each year, with such superb productions as “The Copperhead, “Male and Female, Ireasure Island” and “ On With the Dance” being offered for screen presentation, the public is awakening to a desire to know more of where these and many other of the I ara- mount Pictures are made. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

European Journal of American Studies, 5-4 | 2010 “Don’T Be Frightened Dear … This Is Hollywood”: British Filmmakers in Early A

European journal of American studies 5-4 | 2010 Special Issue: Film “Don’t Be Frightened Dear … This Is Hollywood”: British Filmmakers in Early American Cinema Ian Scott Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/8751 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.8751 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Ian Scott, ““Don’t Be Frightened Dear … This Is Hollywood”: British Filmmakers in Early American Cinema”, European journal of American studies [Online], 5-4 | 2010, document 5, Online since 15 November 2010, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/8751 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.8751 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License “Don’t Be Frightened Dear … This Is Hollywood”: British Filmmakers in Early A... 1 “Don’t Be Frightened Dear … This Is Hollywood”: British Filmmakers in Early American Cinema Ian Scott 1 “Don't be frightened, dear – this – this – is Hollywood.” 2 Noël Coward recited these words of encouragement told to him by the actress Laura Hope-Crews on a Christmas visit to Hollywood in 1929. In typically acerbic fashion, he retrospectively judged his experiences in Los Angeles to be “unreal and inconclusive, almost as though they hadn't happened at all.” Coward described his festive jaunt through Hollywood’s social merry-go-round as like careering “through the side-shows of some gigantic pleasure park at breakneck speed” accompanied by “blue-ridged cardboard mountains, painted skies [and] elaborate grottoes peopled with several familiar figures.”1 3 Coward’s first visit persuaded him that California was not the place to settle and he for one only ever made fleeting visits to the movie colony, but the description he offered, and the delicious dismissal of Hollywood’s “fabricated” community, became common currency if one examines other British accounts of life on the west coast at this time. -

Gloria Swanson

Gloria Swanson: An Inventory of Her Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Swanson, Gloria, 1899-1983 Title: Gloria Swanson Papers [18--]-1988 (bulk 1920-1983) Dates: [18--]-1988 Extent: 620 boxes, artwork, audio discs, bound volumes, film, galleys, microfilm, posters, and realia (292.5 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this well-known American actress encompass her long film and theater career, her extensive business interests, and her interest in health and nutrition, as well as personal and family matters. Call Number: Film Collection FI-041 Language English. Access Open for research. Please note that an appointment is required to view items in Series VII. Formats, Subseries I. Realia. Administrative Information Acquisition Purchase (1982) and gift (1983-1988) Processed by Joan Sibley, with assistance from Kerry Bohannon, David Sparks, Steve Mielke, Jimmy Rittenberry, Eve Grauer, 1990-1993 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Swanson, Gloria, 1899-1983 Film Collection FI-041 Biographical Sketch Actress Gloria Swanson was born Gloria May Josephine Swanson on March 27, 1899, in Chicago, the only child of Joseph Theodore and Adelaide Klanowsky Swanson. Her father's position as a civilian supply officer with the army took the family to Key West, FL and San Juan, Puerto Rico, but the majority of Swanson's childhood was spent in Chicago. It was in Chicago at Essanay Studios in 1914 that she began her lifelong association with the motion picture industry. She moved to California where she worked for Sennett/Keystone Studios before rising to stardom at Paramount in such Cecil B. -

Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema

PERFORMING ARTS • FILM HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF Historical Dictionaries of Literature and the Arts, No. 26 VARNER When early filmgoers watched The Great Train Robbery in 1903, many shrieked in terror at the very last clip, when one of the outlaws turned toward the camera and seemingly fired a gun directly at the audience. The puff of WESTERNS smoke was sudden and hand-colored, and it looked real. Today we can look back at that primitive movie and see all the elements of what would evolve HISTORICAL into the Western genre. Perhaps the Western’s early origins—The Great Train DICTIONARY OF Robbery was the first narrative, commercial movie—or its formulaic yet enter- WESTERNS in Cinema taining structure has made the genre so popular. And with the recent success of films like 3:10 to Yuma and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, the Western appears to be in no danger of disappearing. The story of the Western is told in this Historical Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema through a chronology, a bibliography, an introductory essay, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries on cinematographers; com- posers; producers; films like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Dances with Wolves, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, High Noon, The Magnificent Seven, The Searchers, Tombstone, and Unforgiven; actors such as Gene Autry, in Cinema Cinema Kirk Douglas, Clint Eastwood, Henry Fonda, Jimmy Stewart, and John Wayne; and directors like John Ford and Sergio Leone. PAUL VARNER is professor of English at Abilene Christian University in Abilene, Texas. -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

A Comparison of the Spanish- and English-Language Versions Of

Quiero chupar tu sangre: A Comparison of the Spanish- and English- language versions of Universal Studios’ Dracula (1931) Robert Harland [Dr. Harland teaches Spanish at Mississippi State University. In addition to research and teaching interests in Mexican and European Spanish Literature, he imparts a course in Spanish- language horror movies, one of which is Drácula.] While the English-language version of Dracula (Dir. Tod Browning) is the more famous, especially given its iconic performance by the charismatic Bela Lugosi, the Spanish version, directed by George Melford is in many ways superior. The Anglo adaptation has its place in cultural history assured. Bela Lugosi’s morbid charm, dark hair and genuinely exotic accent gave Dracula a touch of charisma and even authenticity in a film which is often more implausible than the fantastic novel from which it was drawn. Though the line “I want to suck your blood” is never spoken, Lugosi’s accent, his character’s noble lineage, and antiquated, cloaked wardrobe have formed the basic template for all subsequent vampires to follow or avoid. It was a theatre role that Lugosi had previously made his own and which was to haunt him for the rest of his life. Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau’s brilliant silent German adaptation of 1921, Nosferatu, is arguably the much better movie. Alas, Murnau’s film (whose Count Orlok was played by Max Schreck) did not shine in the full glare of the moonlight. Nosferatu was dogged by copyright problems; Lugosi and Browning won first place for their imprint on popular culture. That said, the English version is certainly a poor piece of filmic art on many levels.