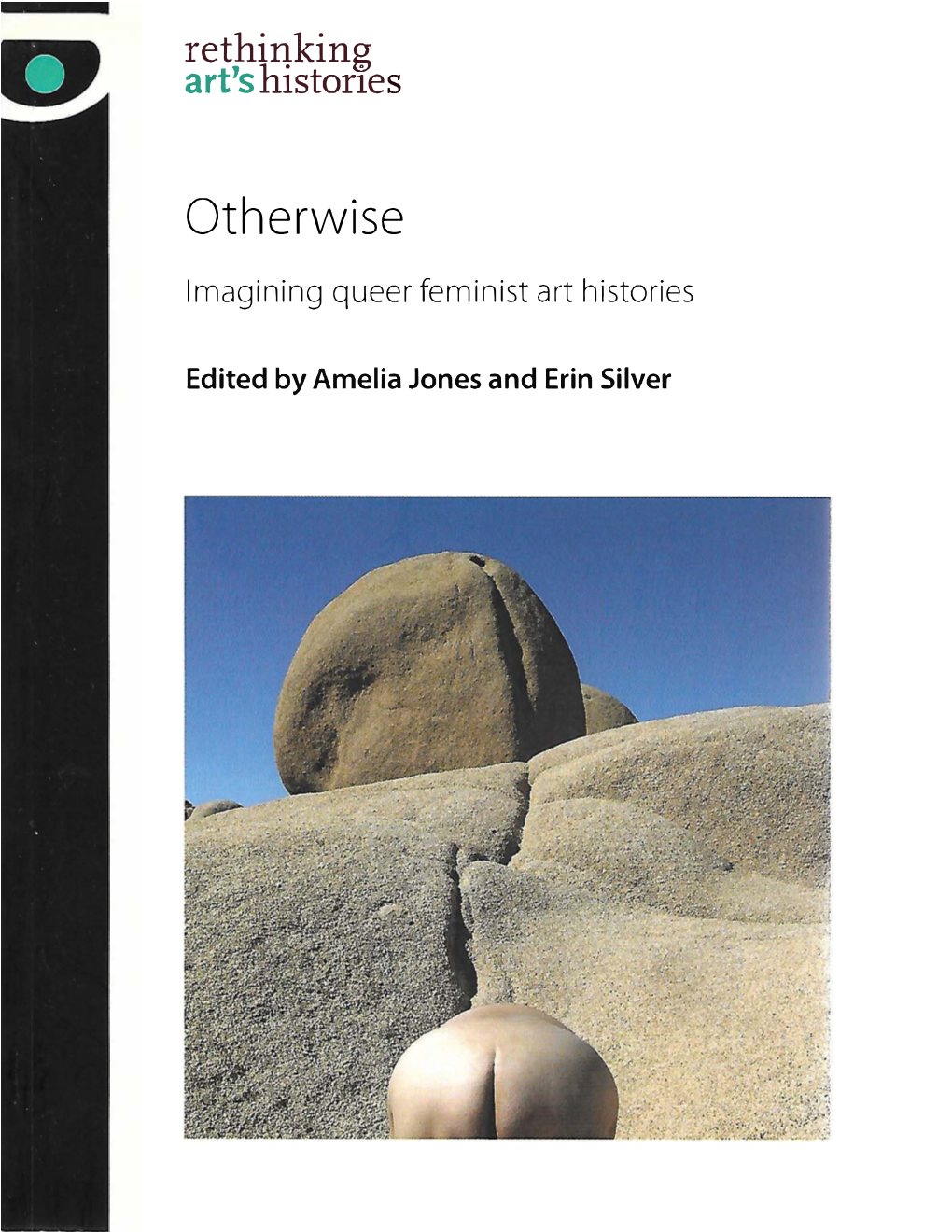

Otherwise Imagining Queer Feminist Art Histories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

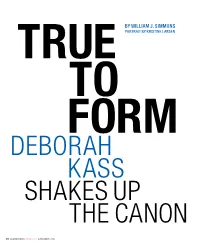

Modern Painters William J. Simmons December 2015

BY WILLIAM J. SIMMONS TRUE PORTRAIT BY KRISTINE LARSEN TO FORM DEBORAH KASS SHAKES UP THE CANON 60 MODERN PAINTERS DECEMBER 2015 BLOUINARTINFO.COM FORM DEBORAH KASS SHAKES UP Deborah Kass in her Brooklyn THE CANON studio, 2015. BLOUINARTINFO.COM DECEMBER 2015 MODERN PAINTERS 61 intensity of her social and art historical themes. The result is a set of tall, sobering, black-and-blue canvases adorned with “THE ONLY ART THAT MATTERS equally hefty neon lettering, akin, perhaps, to macabre monuments or even something more sinister in the tradition of IS ABOUT THE WORLD. pulp horror movies. This is less a departure than a fearless statement that affirms and illuminates her entire oeuvre—a tiny retrospective, perhaps. Fueled by an affinity for the medium AUDRE LORDE SAID IT. TONI and its emotive and intellectual possibilities, Kass has created a template for a disruptive artistic intervention into age-old MORRISON SAID IT. EMILY aesthetic discourses. As she almost gleefully laments, “All these things I do are things that people denigrate. Show tunes— so bourgeois. Formalism—so retardataire. Nostalgia—not a real DICKINSON SAID IT. I’M emotion. I want a massive, fucked-up, ‘you’re not sure what it means but you know it’s problematic’ work of art.” At the core of INTERESTED IN THE WORLD.” Kass’s practice is a defiant rejection of traditional notions of taste. For example, what of Kass’s relationship to feminism, queer- Deborah Kass is taking stock—a moment of reflection on what ness, and painting? She is, for many, a pioneer in addressing motivates her work, coincidentally taking place in her issues of gender and sexuality; still, the artist herself is ambivalent Gowanus studio the day before the first Republican presidential about such claims, as is her right. -

The Charismatic Leadership and Cultural Legacy of Stan Lee

REINVENTING THE AMERICAN SUPERHERO: THE CHARISMATIC LEADERSHIP AND CULTURAL LEGACY OF STAN LEE Hazel Homer-Wambeam Junior Individual Documentary Process Paper: 499 Words !1 “A different house of worship A different color skin A piece of land that’s coveted And the drums of war begin.” -Stan Lee, 1970 THESIS As the comic book industry was collapsing during the 1950s and 60s, Stan Lee utilized his charismatic leadership style to reinvent and revive the superhero phenomenon. By leading the industry into the “Marvel Age,” Lee has left a multilayered legacy. Examples of this include raising awareness of social issues, shaping contemporary pop-culture, teaching literacy, giving people hope and self-confidence in the face of adversity, and leaving behind a multibillion dollar industry that employs thousands of people. TOPIC I was inspired to learn about Stan Lee after watching my first Marvel movie last spring. I was never interested in superheroes before this project, but now I have become an expert on the history of Marvel and have a new found love for the genre. Stan Lee’s entire personal collection is archived at the University of Wyoming American Heritage Center in my hometown. It contains 196 boxes of interviews, correspondence, original manuscripts, photos and comics from the 1920s to today. This was an amazing opportunity to obtain primary resources. !2 RESEARCH My most important primary resource was the phone interview I conducted with Stan Lee himself, now 92 years old. It was a rare opportunity that few people have had, and quite an honor! I use clips of Lee’s answers in my documentary. -

Scholarship Art History (93301) 2015

Scholarship Art History (93301) 2015 — page 1 of 8 Assessment Schedule – 2015 Subject: Scholarship Art History (93301) Candidate answers TWO questions, one from Section A and one from Section B. Each response is marked out of 8 against the descriptors for the Art History Scholarship Standard. A third mark out of 8 is awarded across both responses for communication of arguments. • Schedule 1 relates to the quality required for the two candidate responses. • Schedule 2 relates to the quality required for communication of argument. • Schedule 3 gives, for each question, examples of evidence that might be included in a candidate’s response. Schedule 1: Quality of candidate response (marked separately for each of TWO responses) Outstanding 8 marks 7 marks Scholarship Response shows, in a sustained manner, highly Response fulfils most of the requirements for developed knowledge and understanding of the Outstanding Scholarship, but: discipline through aspects of: visual analysis / critical response level is less perception and insight through highly developed even visual analysis of specific art works and critical or depth and breadth of knowledge is less response to contexts and ideas consistent and sophisticated integration of evidence or independent reflection and extrapolation is demonstrating comprehensive depth and breadth more limited of knowledge relevant to the question or the response is less comprehensive / original. and independent reflection and extrapolation on evidence from varied sources. And the response is original in approach. -

Fifteen Minutes of Fame, Fame in Fifteen Minutes

Andy Warhol and the Dawn of Modern-Day Celebrity Culture 113 Alicja Piechucka Fi!een Minutes of Fame, Fame in Fi!een Minutes: Andy Warhol and the Dawn of Modern-Day Celebrity Culture Life imitates art more than art imitates life. –Oscar Wilde Celebrity is a mask that eats into the face. –John Updike If someone conducted a poll to choose an American personality who best embodies the 1960s, Andy Warhol would be a strong candidate. Pop art, the movement Warhol is typically associated with, !ourished in the 60s. It was also during that decade that Warhol’s career peaked. From 1964 till 1968 his studio, known as the Silver Factory, became not just a hothouse of artistic activity, but also the embodiment of the zeitgeist: the “sex, drugs and rock’n’roll” culture of the period with its penchant for experimentation and excess, the revolution in morals and sexuality (Korichi 182–183, 206–208). "e seventh decade of the twentieth century was also the time when Warhol opened an important chapter in his painterly career. In the early sixties, he started executing celebrity portraits. In 1962, he completed series such as Marilyn and Red Elvis as well as portraits of Natalie Wood and Warren Beatty, followed, a year later, by Jackie and Ten Lizes. In total, Warhol produced hundreds of paintings depicting stars and famous personalities. "is major chapter in his artistic career coincided, in 1969, with the founding of Interview magazine, a monthly devoted to cinema and to the celebration of celebrity, in which Warhol was the driving force. -

Clue # 3 Did You Know? Andy Warhol Produced Around 60 Films

Clue # 3 Did you know? Andy Warhol produced around 60 films. • Andrew Warhola was born on August 6, 1928 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He was a famous artist during the Pop Art movement. His most famous works are Campbell's Soup Cans, Moonwalk, Marilyn Monroe, Che, and Eight Elvises. • He studied art at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. • He worked with different forms of media such as: painting, printmaking, photography, drawing, sculpture, film and music. • On one of his first jobs his name was misspelled as "Warhol“ and he liked it. • He explored pop culture with brands like Coca Cola, Campbells’ and Watties' soup. In 1961, he began to mass-produce commercial goods with his art. He called it Pop Art. One example was the Campbell's Soup cans. In one of his paintings, he had two hundred Campbell's soup cans. • Andy also used pictures of famous people, repeating the same portrait over and over in different colors. He painted Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, Elizabeth Taylor, and Mao Zedong. He used bright colors and silk screening techniques to create his artwork in large quantities. • He opened a new art studio called "The Factory" where he painted, held parties and sold a lot of his art to celebrities. He also founded the New York Academy of Art in 1979. • In 1968, he was shot three times by a woman named Valerie Solanas but he survived. What was the name of his studio where he sold art to celebrities? Question A. Carnegie Mellon B. New York Academy of Art C. Solanas Question D. -

Academic Writing

Academic Writing Most international students need to write essays and reports for exams and coursework, but writing good academic English is one of the most demanding tasks students face. This new, fourth edition of Academic Writing: A Handbook for International Students has been completely revised to help students reach this goal. The four main parts of Academic Writing are: • The Writing Process • Elements of Writing • Vocabulary for Writing • Writing Models Each part is divided into short units that contain examples, explanations and exercises, for use in the classroom or for self-study. The units are clearly organised to allow teachers and students to find the help they need with writing tasks, while cross-referencing allows easy access to relevant sections. In the first part, each stage of the writing process is demonstrated and practised, from selecting suitable sources, reading, note-making and planning through to rewriting and proofreading. The fourth edition of this popular book builds on the success of the earlier editions, and has a special focus on the vital topic of academic vocabulary in Part 3, ‘Vocabulary for Writing’. Part 3 deals with areas such as nouns and adjectives, adverbs and verbs, synonyms, prefixes and prepositions, in an academic context. More key features of the book include: • All elements of writing are clearly explained, with a full glossary for reference • Models provided for all types of academic texts: essays, reports, reviews and case studies • Full range of practice exercises, with answer key included • Use of authentic academic texts • A companion website offers further practice with a range of additional exercises • Fully updated, with sections on finding electronic sources and evaluating Internet material All international students wanting to maximise their academic potential will find this practical and easy-to-use book an invaluable guide to writing in English for their degree courses. -

To Consignors Hip Color & No

Index to Consignors Hip Color & No. Sex Sire Dam Dam's Sire Barn 27 Property of The Acorn LLC 809 dk. b./br. f. Old Trieste Pride of Yoda Time for a Change Barn 27 Consigned by The Acorn LLC, Agent for White Oaks 548 b. f. Fusaichi Pegasus Word o' Ransom Red Ransom 688 gr/ro. c. Spinning World Grab the Green Cozzene 820 b. f. War Chant Reach the Top Cozzene Barn 35 Consigned by Ballinswood Sales (Bill Murphy), Agent for Creston Farms 669 dk. b./br. c. Dynaformer Footy Topsider 751 dk. b./br. c. Old Trieste Marchtothemine Mining Barn 46 Consigned by Bedouin Bloodstock, Agent I 1029 ch. c. Forest Wildcat Erstwhile Arts and Letters 1161 dk. b./br. c. Awesome Again Naked Glory Naked Sky Barn 42 Consigned by Blackburn Farm (Michael T. Barnett), Agent 1009 dk. b./br. f. Touch Gold Deep Enough Raise a Native Barn 42 Consigned by Blackburn Farm (Michael T. Barnett), Agent for Classic Run Farm 1063 dk. b./br. c. Menifee Hail the Queen Danzatore 1100 ch. f. Belong to Me Kris Is It Kris S. Barn 42 Consigned by Blackburn Farm (Michael T. Barnett), Agent for Longleaf Pine Farm 971 dk. b./br. c. Chester House Bittersweet Hour Seattle Slew Barn 29 Consigned by Blake Agency, Agent 589 b. f. Thunder Gulch Bet Birdie Bet Twice 819 b. c. Summer Squall Rainbow Promise Known Fact 870 ch. c. Distorted Humor Slick Delivery Topsider Barn 44 Consigned by Blandford Stud (Padraig Campion), Agent 957 dk. b./br. c. Giant's Causeway Aunt Pearl Seattle Slew 1185 ch. -

Elvis Quarterly 89 Ned

UEPS QUARTERLY 89 Driemaandelijks / Trimestriel januari-februari-maart 2009 / Afgiftekantoor Antwerpen X - erk. nr.: 708328 januari-februari-maart 2009 / Afgiftekantoor Antwerpen X - erk. nr.: Driemaandelijks / Trimestriel The United Elvis Presley Society is officieel erkend door Elvis en Elvis Presley Enterprises (EPE) sedert 1961 The United Elvis Presley Society Elvis Quarterly Franstalige afdeling: Driemaandelijks tijdschrift Jean-Claude Piret - Colette Deboodt januari-februari-maart 2009 Rue Lumsonry 2ème Avenue 218 Afgiftekantoor: Antwerpen X - 8/1143 5651 Tarcienne Verantwoordelijk uitgever: tel/fax 071 214983 Hubert Vindevogel e.mail: [email protected] Pijlstraat 15 2070 Zwijndrecht Rekeningnummers: tel/fax: 03 2529222 UEPS (lidgelden, concerten) e-mail: [email protected] 068-2040050-70 www.ueps.be TCB (boetiek): Voorzitter: 220-0981888-90 Hubert Vindevogel Secretariaat: Nederland: Martha Dubois Giro 2730496 (op naam van Hubert Vindevogel) IBAN: BE34 220098188890 – BIC GEBABEBB (boetiek) Medewerkers: IBAN: BE60 068204005070 – BIC GCCCBEBB (lidgelden – concerten) Tina Argyl Cecile Bauwens Showroom: Daniel Berthet American Dream Leo Bruynseels Dorp West 13 Colette Deboodt 2070 Zwijndrecht Pierre De Meuter tel: 03 2529089 (open op donderdag, vrijdag en zaterdag van 10 tot 18 uur Marc Duytschaever - Eerste zondag van elke maand van 13 tot 18 uur) Dominique Flandroit Marijke Lombaert Abonnementen België Tommy Peeters 1 jaar lidmaatschap: 18 € (vier maal Elvis Quarterly) Jean-Claude Piret 2 jaar: 32 € (acht maal Elvis Quarterly) Veerle -

Lucy Sparrow Photo: Dafydd Jones 18 Hot &Coolart

FREE 18 HOT & COOL ART YOU NEVER FELT LUCY SPARROW LIKE THIS BEFORE DAFYDD JONES PHOTO: LUCY SPARROW GALLERIES ONE, TWO & THREE THE FUTURE CAN WAIT OCT LONDON’S NEW WAVE ARTISTS PROGRAMME curated by Zavier Ellis & Simon Rumley 13 – 17 OCT - VIP PREVIEW 12 OCT 6 - 9pm GALLERY ONE PETER DENCH DENCH DOES DALLAS 20 OCT - 7 NOV GALLERY TWO MARGUERITE HORNER CARS AND STREETS 20 - 30 OCT GALLERY ONE RUSSELL BAKER ICE 10 NOV – 22 DEC GALLERY TWO NEIL LIBBERT UNSEEN PORTRAITS 1958-1998 10 NOV – 22 DEC A NEW NOT-FOR-PROFIT LONDON EXHIBITION PLATFORM SUPPORTING THE FUSION OF ART, PHOTOGRAPHY & CULTURE Art Bermondsey Project Space, 183-185 Bermondsey Street London SE1 3UW Telephone 0203 441 5858 Email [email protected] MODERN BRITISH & CONTEMPORARY ART 20—24 January 2016 Business Design Centre Islington, London N1 Book Tickets londonartfair.co.uk F22_Artwork_FINAL.indd 1 09/09/2015 15:11 THE MAYOR GALLERY FORTHCOMING 21 CORK STREET, FIRST FLOOR, LONDON W1S 3LZ TEL: +44 (0) 20 7734 3558 FAX: +44 (0) 20 7494 1377 [email protected] www.mayorgallery.com EXHIBITIONS WIFREDO ARCAY CUBAN STRUCTURES THE MAYOR GALLERY 13 OCT - 20 NOV Wifredo Arcay (b. 1925, Cuba - d. 1997, France) “ETNAIRAV” 1959 Latex paint on plywood relief 90 x 82 x 8 cm 35 1/2 x 32 1/4 x 3 1/8 inches WOJCIECH FANGOR WORKS FROM THE 1960s FRIEZE MASTERS, D12 14 - 18 OCT Wojciech Fangor (b.1922, Poland) No. 15 1963 Oil on canvas 99 x 99 cm 39 x 39 inches STATE_OCT15.indd 1 03/09/2015 15:55 CAPTURED BY DAFYDD JONES i SPY [email protected] EWAN MCGREGOR EVE MAVRAKIS & Friend NICK LAIRD ZADIE SMITH GRAHAM NORTON ELENA SHCHUKINA ALESSANDRO GRASSINI-GRIMALDI SILVIA BRUTTINI VANESSA ARELLE YINKA SHONIBARE NIMROD KAMER HENRY HUDSON PHILIP COLBERT SANTA PASTERA IZABELLA ANDERSSON POPPY DELEVIGNE ALEXA CHUNG EMILIA FOX KARINA BURMAN SOPHIE DAHL LYNETTE YIADOM-BOAKYE CHIWETEL EJIOFOR EVGENY LEBEDEV MARC QUINN KENSINGTON GARDENS Serpentine Gallery summer party co-hosted by Christopher Kane. -

Art in the Age of the Coronavirus June 6 - December 12, 2020

Life During Wartime: Art in the Age of the Coronavirus June 6 - December 12, 2020 Deborah Kass “I use history as a readymade,” Deborah Kass has declared. “I use the language of painting to talk about value and meaning. How has art history constructed power and meaning? How has it reflected the culture at large? How does art and the history of art describe power?” Most discourses around power and meaning today are—or should be—undergoing serious reconsideration. Theories of knowledge have bent to the breaking point. The combined weight of political instability, alternative facts, a growing rejection of science and the destabilizing effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as the growing use of state violence, have mined the confidence of people around the world but of Americans especially. Enter Deborah Kass’s Feel Good Paintings For Feel Bad Times. A set of canvases that use language and the sanctioned stylings of celebrated male artists to express key cultural conflicts, they marshal wit and graphic punch to force a confrontation between the canonical (the orthodoxies established by male artists) and the disruptive (their appropriation by a female artist). The results are demystifying, cutting, and often hilarious. They are also hopeful. At times being funny is simply saying what’s true. — CVF, USFCAM Deborah Kass, Isn’t It Rich, 2009. Oil and acrylic on canvas. 72 x 72 in. (182.88 x 182.88 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Kavi Gupta, Chicago, IL. Photo by Christopher Burke. Deborah Kass, Painting With Balls, 2005. Oil on linen. 84 x 60 in. -

TRIB LIVE | Aande

TRIB LIVE | AandE Artist displays her Warhol roots By Kurt Shaw Published: Saturday, November 3, 2012, 9:03 p.m. Updated: Sunday, November 4, 2012 Many artists strive to replicate the success of Andy Warhol, but few have replicated his art like Deborah Kass. The New York City-based artist spent eight years working in the vein of the Pop Art king, only to create something uniquely her own. “There’s no artist of my generation for whom Andy is not an influence. I mean, he was huge in everyone’s consciousness,” says Kass, a 1974 graduate of Carnegie Mellon University’s art department. Kass, who was born and raised in Long Island, says Warhol was a big reason she chose to attend Carnegie Mellon. But it wouldn’t be until nearly 20 years later that she would mine the artist’s oeuvre for ideas and inspiration. Now, the artist and her influence meet again, but in a different way. Just last weekend, Kass, 60, was in town for the opening of her first retrospective, “Deborah Kass: Before and Deborah Kass‘Before and Happily Ever After’ 1991 Happily Ever After.“ And it’s on display at, where else, The Andy Warhol Museum. At first glance, you might be hard pressed to tell a Warhol from a Kass, especially on the fourth floor of the museum where no fewer than 10 Warhol-inspired portraits by Kass of her friends hang alongside nearly as many by Warhol. There’s Warhol’s portrait of his friend, Victor Hugo, next to Kass’ friend, Norman Kleeblatt, fine-arts curator at the Jewish Museum in NewYork. -

Vintage Game Consoles: an INSIDE LOOK at APPLE, ATARI

Vintage Game Consoles Bound to Create You are a creator. Whatever your form of expression — photography, filmmaking, animation, games, audio, media communication, web design, or theatre — you simply want to create without limitation. Bound by nothing except your own creativity and determination. Focal Press can help. For over 75 years Focal has published books that support your creative goals. Our founder, Andor Kraszna-Krausz, established Focal in 1938 so you could have access to leading-edge expert knowledge, techniques, and tools that allow you to create without constraint. We strive to create exceptional, engaging, and practical content that helps you master your passion. Focal Press and you. Bound to create. We’d love to hear how we’ve helped you create. Share your experience: www.focalpress.com/boundtocreate Vintage Game Consoles AN INSIDE LOOK AT APPLE, ATARI, COMMODORE, NINTENDO, AND THE GREATEST GAMING PLATFORMS OF ALL TIME Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton First published 2014 by Focal Press 70 Blanchard Road, Suite 402, Burlington, MA 01803 and by Focal Press 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Focal Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2014 Taylor & Francis The right of Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.