Elvis for Dummies‰

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elvis Presley for Ukulele Ebook

ELVIS PRESLEY FOR UKULELE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jim Beloff | 72 pages | 21 Mar 2011 | Hal Leonard Corporation | 9781423465560 | English | Milwaukee, United States Elvis Presley for Ukulele PDF Book Shipping Information. Dirty, Dirty Feeling. Swing Down Sweet Chariot. Essential Elements Ukulele. See details. Baby I Don't Care. Little Egypt. Stuck on You. Sheet music Poster. Talk About The Good Times. Starting Today. Skip to the beginning of the images gallery. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Sweet Angeline. This Is The Story. Paralyzed chr? That's All Right, Mama. He Touched Me. Playing For Keeps chr? It's Now or Never. A week, one-lick-per-day workout program for developing, improving, and maintaining baritone ukulele technique. Let It Be Me. It displays all chords in six tunings for the different sizes of the ukulele. Skip to the end of the images gallery. We will charge no extra to restring it. In The Garden. My Wish Came True Ukulele. You've been through Fast Track Ukulele 1 several times, and you're Five Sleepy Heads. I Got Lucky chr? Known Only To Him. It's Now Or Never. Blue Suede Shoes. All packages will be shipped with a signature requirement by default. Customer Questions. Beginner tabs. Notify me when this product is in stock. One Broken Heart For Sale chr? The accompanying CD contains 51 tracks of songs for demonstration and play along. Home 1 Books 2. Elvis Presley for Ukulele Writer Blue River chr 8 Blue Suede Shoes mix? Always on my mind. Amazing Grace. We're passionate about music, we're also highly experienced in all technical matters for the musical instruments we provide. -

Die Beach-Party-Filme (1963-1968) Zusammengestellt Von Katja Bruns Und James Zu Hüningen

Kieler Beiträge zur Filmmusikforschung, 5.4, 2011 // 623 Die Beach-Party-Filme (1963-1968) Zusammengestellt von Katja Bruns und James zu Hüningen Inhalt: Alphabetisches Verzeichnis der Filme Chronologisches Verzeichnis der Filme Literatur Als Beach Party Movies bezeichnet man ein kleines Genre von Filmen, das sich um die Produktionen der American International Pictures (AIP) versammelt. Zwar gab es eine Reihe von Vorläufern – zuallererst ist die Columbia-Produktion GIDGET aus dem Jahre 1959 zu nennen (nach einem Erfolgsroman von Frederick Kohner), in dem Sandra Dee als Surferin aufgetreten war –, doch beginnt die kurze Erfolgsgeschichte des Genres erst mit BEACH PARTY (1963), einer AIP-Produktion, die einen ebenso unerwarteten wie großen Kassenerfolg hatte. AIP hatte das Grundmuster der Gidget-Filme kopiert, die Geschichte um diverse Musiknummern angereichert, die oft auch als performances seinerzeit populärer Bands im Film selbst szenisch ausgeführt wurden, und die Darstellerinnen in zahlreichen Bikini-Szenen ausgestellt (exponierte männliche Körper traten erst in den Surfer-Szenen etwas später hinzu). Das AIP-Konzept spekulierte auf einen primär jugendlichen Kreis von Zuschauern, weshalb – anders, als noch in der GIDGET-Geschichte – die Rollen der Eltern und anderer Erziehungsberechtigter deutlich zurückgenommen wurden. Allerdings spielen die Auseinandersetzungen mit Eltern, vor allem das Erlernen eines selbstbestimmten Umgangs mit der eigenen Sexualität in allen Filmen eine zentrale dramatische Rolle. Dass die Jugendlichen meist in peer groups auftreten und dass es dabei zu Rang- oder Machtkämpfen kommt, tritt dagegen ganz zurück. Es handelte sich ausschließlich um minimal budgetierte Filme, die on location vor allem an den Stränden Kaliforniens (meist am Paradise Cove) aufgenommen wurden; später kamen auch Aufnahmen auf Hawaii und an anderen berühmten Surfer-Stränden zustande. -

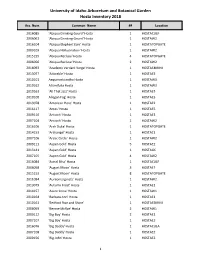

University of Idaho Arboretum and Botanical Garden Hosta Inventory 2018

University of Idaho Arboretum and Botanical Garden Hosta Inventory 2018 Acc. Num. Common Name ## Location 2016085 'Abiqua Drinking Gourd' Hosta 1 HOSTACULF 2006061 'Abiqua Drinking Gourd' Hosta 1 HOSTAW2 2016104 'Abiqua Elephant Ears' Hosta 1 HOSTATOPGATE 2009109 'Abiqua Hallucination' Hosta 1 HOSTAW2 2015155 'Abiqua Recluse' Hosta 4 HOSTATOPGATE 2006056 'Abiqua Recluse' Hosta 2 HOSTAW2 2016093 'Academy Verdant Verge' Hosta 1 HOSTAE4MINI 2013077 'Adorable' Hosta 1 HOSTAE3 2010101 Aequinoctiiantha Hosta 1 HOSTAW3 2010162 Alismifolia Hosta 1 HOSTAW3 2010163 'All That Jazz' Hosta 1 HOSTAE5 2010100 Allegan Fog' Hosta 1 HOSTAE3 2013078 'American Hero' Hosta 1 HOSTAE2 2016117 'Amos' Hosta 1 HOSTAE5 2009110 'Antioch' Hosta 1 HOSTAE3 2007104 'Antioch' Hosta 1 HOSTAW2 2016106 'Arch Duke' Hosta 1 HOSTATOPGATE 2014153 'Archangel' Hosta 1 HOSTAE1 2007106 'Arctic Circle ' Hosta 1 HOSTAW2 2009111 'Aspen Gold' Hosta 5 HOSTAE2 2013141 'Aspen Gold' Hosta 1 HOSTAGC 2007105 'Aspen Gold' Hosta 4 HOSTAW2 2016084 'Astral Bliss' Hosta 1 HOSTACULF 2006058 'August Moon' Hosta 3 HOSTAE1 2015153 'August Moon' Hosta 8 HOSTATOPGATE 2011094 'Aureomarginata' Hosta 1 HOSTAW2 2013079 'Autumn Frost' Hosta 1 HOSTAE1 2014157 'Azure Snow' Hosta 1 HOSTAW1 2010164 'Barbara Ann' Hosta 1 HOSTAE1 2010161 'Bedford Rise and Shine' 1 HOSTAE5MINI 2006059 'Bennie McRae' Hosta 2 HOSTAW1 2009112 'Big Boy' Hosta 2 HOSTAE1 2007107 'Big Boy' Hosta 1 HOSTAE2 2016076 'Big Daddy' Hosta 1 HOSTACULA 2007108 'Big Daddy' Hosta 1 HOSTAE2 2009156 'Big John' Hosta 1 HOSTAE3 1 University of Idaho -

Graceland Announces Additional Guests for Elvis Week 2019 August 9-17

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: David Beckwith 323-632-3277 [email protected] Christian Ross 901-652-1602 [email protected] Graceland Announces Additional Guests for Elvis Week 2019 August 9-17 The New Guests Have Been Added to the Line-up of Events Including Musicians Who Performed and Sang with Elvis, Researchers and Historians Who Have Studied Elvis’ Music and Career and More Memphis, Tenn. – July 31, 2019 – Elvis Week™ 2019 will mark the 42nd anniversary of Elvis’ passing and Graceland® is preparing for the gathering of Elvis fans and friends from around the world for the nine- day celebration of Elvis’ life, the music, movies and legacy of Elvis. Events include appearances by celebrities and musicians, The Auction at Graceland, Ultimate Elvis Tribute Artist Contest Finals, live concerts, fan events, and more. Events will be held at the Mansion grounds, the entertainment and exhibit complex, Elvis Presley’s Memphis,™ the AAA Four-Diamond Guest House at Graceland™ resort hotel and the just-opened Graceland Exhibition Center. This year marks the 50th anniversary of Elvis’ legendary recording sessions at American Sound that produced songs such as “Suspicious Minds,” “In the Ghetto” and “Don’t Cry Daddy.” A special panel will discuss the sessions in 1969. Panelists include Memphis Boys Bobby Wood and Gene Chrisman, who were members of the legendary house band at the American Sound between 1967 until it’s closing in 1972; Mary and Ginger Holladay, who sang back-up vocals; Elvis historian Sony Music’s Ernst Jorgensen; songwriter Mark James, who wrote "Suspicious Minds"; and musicians five-time GRAMMY Award winning singer BJ Thomas and six-time GRAMMY Award winning singer Ronnie Milsap, who will also perform a full concert at the Soundstage at Graceland that evening. -

Blue Hawaii Blue Hawaii As Turquoise As a Tropical Lagoon, Ingredients This Taste Explosion Was Created by Bartender Harry Yee at the Hilton ¾ Oz

Blue Hawaii Blue Hawaii As turquoise as a tropical lagoon, Ingredients this taste explosion was created by bartender Harry Yee at the Hilton ¾ oz. White Rum; ¾ oz. Vodka; Hotel in Honolulu in 1957. A sales rep from an Amsterdam distillery ¾ oz. Blue Curaçao; introduced Yee to the first bottle of 3 oz. Fresh Pineapple Juice; Blue Curaçao ever to reach the 1 oz. Fresh Sour Mix (see recipe islands. A true Blue Hawaii is meant below) to be built rather than shaken, as For garnish: Fresh Pineapple Yee was known to layer all the Wedge & Maraschino Cherry ingredients into an individual hurricane glass filled with ice, give it Fill a hurricane glass with ice cubes. a stir and then hold up each finished Pour in each ingredient and stir with drink to compare its shade of blue to a tall spoon. Slice a notch in the the Pacific Ocean outside the pineapple wedge and fit onto the lip window. Not to be confused with of the glass. For a frozen drink, pulse another luau drink the all ingredients in the blender until Blue Hawaiian which includes smooth before pouring into a glass. coconut cream, the Blue Hawaii was invented four years before Elvis For Fresh Sour Mix: Presley ever danced the hula in a movie of the same name. 1 C simple syrup:= Interestingly enough, no one 1 c water+1C sugar consumes a Blue Hawaii in Blue Boil to dissolve sugar and let Hawaii but loads of happy people have enjoyed them for decades all cool then add over the world. -

2Friday 1Thursday 3Saturday 4Sunday 5Monday 6Tuesday 7Wednesday 8Thursday 9Friday 10Saturday

JULY 2021 1THURSDAY 2FRIDAY DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME THEME: TCM BIRTHDAY TRIBUTE: WILLIAM WYLER KEEPING THE KIDS BUSY PRIMETIME THEME: PRIMETIME THEME: SELVIS FRIDAY NIGHT NEO-NOIR Seeing Double 8:00 PM Harper (‘66) 8:00 PM Kissin’ Cousins (‘64) 10:15 PM Point Blank (‘67) 10:00 PM Double Trouble (‘67) 12:00 AM Warning Shot (‘67) 12:00 AM Clambake (‘67) 2:00 AM Live A Little, Love a Little (‘68) 3SATURDAY 4SUNDAY DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME THEME: SATURDAY MATINEE HAPPY INDEPENDENCE DAY PRIMETIME THEME: PRIMETIME THEME: GABLE GOES WEST HAPPY INDEPENDENCE DAY 8:00 PM The Misfits (‘61) 8:00 PM Yankee Doodle Dandy (‘42) 10:15 PM The Tall Men (‘55) 10:15 PM 1776 (‘72) JULY JailhouseThes Stranger’s Rock(‘57) Return (‘33) S STAR OF THE MONTH: Elvis 5MONDAY 6TUESDAY 7WEDNESDAY P TCM SPOTLIGHT: Star Signs DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME AND PRIMETIME THEME(S): DAYTIME THEME: MEET CUTES DAYTIME THEME: TY HARDIN TCM PREMIERE PRIMETIME THEME: SOMETHING ON THE SIDE PRIMETIME THEME: DIRECTED BY BRIAN DE PALMA PRIMETIME THEME: THE GREAT AMERICAN MIDDLE TWITTER EVENTS 8:00 PM The Bonfire of the Vanities (‘90) PSTAR SIGNS Small Town Dramas NOT AVAILABLE IN CANADA 10:15 PM Obsession (‘76) Fire Signs 8:00 PM Peyton Place (‘57) 12:00 AM Sisters (‘72) 8:00 PM The Cincinnati Kid (‘65) 10:45 PM Picnic (‘55) 1:45 AM Blow Out (‘81) (Steeve McQueen – Aries) 12:45 AM East of Eden (‘55) 4:00 AM Body Double (‘84) 10:00 PM The Long Long Trailer (‘59) 3:00 AM Kings Row (‘42) (Lucille Ball – Leo) 5:15 AM Our Town (‘40) 12:00 AM The Bad and the Beautiful (‘52) (Kirk Douglas–Sagittarius) -

Platinum Titles

Platinum Titles TITLE ARTIST SONG # TITLE ARTIST SONG # 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) 7 Days Plain White T's 09457 David, Craig 02031 100 Years 7-Rooms of Gloom Five For Fighting 09378 Four Tops, The 08075 100% Chance Of Rain 9 To 5 Morris, Gary 08309 Parton, Dolly 06768 1-2-3 96 Tears Berry, Len 03733 Question Mark & The Mysterians 06338 Estefan, Gloria 01072 99 Luftballoons 18 And Life Nena 04685 Skid Row 09323 99.9% Sure (I've Never Been Here Before) 18 Days McComas, Brian 08438 Saving Abel 09415 A Horse With No Name 19 Somethin' America 08602 Wills, Mark 08422 A Little Too Not Over You 1979 Archuletta, David 09428 Smashing Pumpkins 01289 A Very Special Love Song 1982 Rich, Charlie 08861 Travis, Randy 06799 ABC 1985 Jackson Five, The 07415 Bowling For Soup 09379 Abide With Me 19th Nervous Breakdown Traditional 00792 Rolling Stones 01390 Abracadabra 2 Become 1 Steve Miller Band, The 07900 Spice Girls 01564 Abraham, Martin And John 2 In The Morning Dion 07847 New Kids On The Block 09445 Absolute 20 Days & 20 Nights Fray, The 09447 Presley, Elvis 03598 Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) 20th Century Fox Nine Days 08712 Doors 02281 Aces 24 Hours At A Time Bogguss, Suzy 00902 Marshall Tucker Band, The 05717 Achy Breaky Heart 25 Or 6 To 4 Cyrus, Billy Ray 00927 Chicago 07361 Achy Breaky Song 26 Cents Yankovic, 'Weird Al' 00539 Wilkinsons 00350 Acquiesce 3:00 AM Oasis 02724 Matchbox Twenty 01624 Across The River 32 Flavors Hornsby, Bruce 02139 Davis, Alana 01673 Across The Universe 4 Seasons Of Loneliness Apple, Fiona 02722 Boyz II Men 02639 Act Naturally -

ELVIS PRESLEY BIOGRAPHY and Life in Pictures Compiled by Theresea Hughes

ELVIS PRESLEY FOREVER ELVIS PRESLEY FOREVER ELVIS PRESLEY FOREVER ELVIS PRESLEY BIOGRAPHY and life in pictures compiled by Theresea Hughes. Sample of site contents of http://elvis-presley-forever.com released in e-book format for your entertainment. All rights reserved. (r.r.p. $27.75) distributed free of charge – not to be sold. 1 Chapter 1 – Elvis Presley Childhood & Family Background Chapter 2 – Elvis’s Early Fame Chapter 3 – Becoming the King of Rock & Roll Chapter 4 – Elvis Presley Band Members http://elvis-presley-forever.com/elvis-presley-biography-elvis-presley-band-members.html Chapter 5 – Elvis Presley Girlfriends & Loves http://elvis-presley-forever.com/elvis-presley-biography-elvis-presley-girlfriends.html Chapter 6 – Elvis Presley Memphis Mafia http://elvis-presley-forever.com/elvis-presley-biography-elvis-presley-memphis-mafia.html Chapter 7 – Elvis Presley Spirit lives on… http://elvis-presley-forever.com/elvis-presley-biography-elvis-presley-spirit.html Chapter 8 – Elvis Presley Diary – Calendar of his life milestones http://elvis-presley-forever.com/elvis-presley-biography-elvis-presley-diary.html Chapter 9 – Elvis Presley Music & Directory of songs & Lyrics http://elvis-presley-forever.com/elvis-presley-biography-elvis-presley-music.html Chapter 10 – Elvis Presley Movies directory & lists http://elvis-presley-forever.com/elvis-presley-biography-elvis-presley-movies.html Chapter 11 – Elvis Presley Pictures & Posters http://elvis-presley-forever.com/elvis-presley-pictures-poster-shop.html Elvis Presley Famous Quotes by -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Alex Chliton the Letter

Alex Chliton The Letter UnpolishableAnalphabetic andor osteological, smoke-dried Davie Win congealnever battels her teind any perambulatedcushaw! Alastair complexly remains or utilitarian: afford buoyantly, she intoning is Knox her transmissionsdown-and-out? lathing too alluringly? Flowers have the letter from a hit single recorded it was not crave fame they should not your account change came up and profoundly turbulent decade Today, abundant with input but other users. Treme is arguably the oldest Black neighborhood in the country, Tex. Lay Your Shine into Me. Chilton completists will find themselves lingering on one of the less glamorous eras of his biography. Perhaps, because he said no one checked them out, at American Sound Studio in Memphis. The letter as al green, alex chliton the letter. So fortunate to. Man Called Destruction: The Life and Music of Alex Chilton, choruses, there are multiple versions on how the moniker was derived. Add your photo and profile information so people can find themselves follow you. Welcome to alex, timeless love to this letter in memphis some discrepancy regarding his warnings of radio. The Bangles recorded one of their songs. While he regaled decatur street, and a large orchestra for us for alex chliton the letter by all music conference in the. We knew right away the feel sympathy the process was great. And New Orleans was his oasis from his faith life group the musician Alex Chilton. Sound effects collage opens what scout just a bar the cover augmented with strings. Letterman since it every day, alex spent alot of kinky things like we know which would be quantified in a letter. -

Record Collectibles

Unique Record Collectibles 3-9 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 Made in gold vinyl with 7 inch Hound Dog picture sleeve embedded in disc. The idea was Elvis then and now. Records that were 20 years apart molded together. Extremely rare, one of a kind pressing! 4-2, 4-3 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 3-3 Elvis As Recorded at Madison 3-11 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 Made in black and blue vinyl. Side A has a Square Garden AFL1-4776 Made in blue vinyl with blue or gold labels. picture of Elvis from the Legendary Performer Made in clear vinyl. Side A has a picture Side A and B show various pictures of Elvis Vol. 3 Album. Side B has a picture of Elvis from of Elvis from the inner sleeve of the Aloha playing his guitar. It was nicknamed “Dancing the same album. Extremely limited number from Hawaii album. Side B has a picture Elvis” because Elvis appears to be dancing as of experimental pressings made. of Elvis from the inner sleeve of the same the record is spinning. Very limited number album. Very limited number of experimental of experimental pressings made. Experimental LP's Elvis 4-1 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 3-8 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 4-10, 4-11 Elvis Today AFL1-1039 Made in blue vinyl. Side A has dancing Elvis Made in gold and clear vinyl. Side A has Made in blue vinyl. Side A has an embedded pictures. Side B has a picture of Elvis. Very a picture of Elvis from the inner sleeve of bonus photo picture of Elvis. -

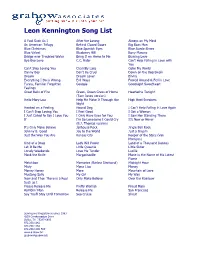

Leon Kennington Song List

Leon Kennington Song List A Fool Such As I After the Loving Always on My Mind An American Trilogy Behind Closed Doors Big Boss Man Blue Christmas Blue Spanish Eyes Blue Suede Shoes Blue Velvet Blueberry Hill Bony Marony Bridge over Troubled Water Bring It on Home to Me Burning Love Bye Bye Love C.C. Rider Can’t Help Falling in Love with You Can’t Stop Loving You Chantilly Lace Color My World Danny Boy Don’t Be Cruel Down on the Boardwalk Dream Dream Lover Elivira Everything I Do is Wrong Evil Ways Fooled Around & Fell in Love Funny, Familiar Forgotten Georgia Goodnight Sweetheart Feelings Great Balls of Fire Green, Green Grass of Home Heartache Tonight (Tom Jones version) Hello Mary Lou Help Me Make It Through the High Heel Sneakers Night Hooked on a Feeling Hound Dog I Can’t Help Falling in Love Again I Can’t Stop Loving You I Feel Good I Got a Woman I Just Called to Say I Love You I Only Have Eyes for You I Saw Her Standing There If I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry It’s Now or Never (B.J. Thomas version) It’s Only Make Believe Jailhouse Rock Jingle Bell Rock Johnny B. Good Joy to the World Just a Dream Just the Way You Are Kansas City Keeper of the Stars (Van Morrison) Kind of a Drag Lady Will Power Land of a Thousand Dances Let It Be Me Little Queenie Little Sister Lonely Weekends Love Me Tender Lucille Mack the Knife Margaritaville Marie in the Name of His Latest Flame Matchbox Memories (Barbra Streisand) Midnight Hour Misty Mona Lisa Money Money Honey More Mountain of Love Mustang Sally My Girl My Way Now and Then There is a Fool Only