“Putting Innovation in Place: Georgia Tech's Innovation Neighbourhood of 'Tech Square'”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making It LOUD

Making it LOUD 2011 Annual Report WWW.USFIRST.ORG1 For over 20 years, FIRST® Founder Dean Kamen and everyone associated with FIRST have been on a mission to spread President Barack Obama, along with White House Technology Officer Aneesh Chopra, continued to feature FIRST teams as perfect examples of the president’s national White the word about the many educational, societal, economical, and House Science Fair initiative promoting STEM (science, technology, engineering, and Dean Kamen will.i.am planetary benefits of getting youth and adults alike involved in theFIRST math) education and celebrating science and math achievement in American schools. Morgan Freeman experience. Despite not having access to the millions of marketing Soledad O’Brien dollars required to make FIRST a household “brand,” the program has continued to grow each year at a blistering pace. …aND loudER Books, magazines, newspapers, cable TV, and the Web helped us create noise, too, with ongoing national coverage by Bloomberg, CNN, Popular Mechanics, In 2011, however, thanks to the fervent interest of major figures Popular Science, Wired, ESPN Magazine, WallStreetJournal.com, and more. Author Neal Bascomb brought the FIRST experience to life in his inspiring in government, the media, and mainstream entertainment, the book, The New Cool.Time Warner Cable incorporated “volume” of voices promoting FIRST... FIRST into its national “Connect A Million Minds™” initiative, featuring our FRC program in its TV show “It Ain’t Rocket Science.” The clamor of FIRST recognition continues to grow ...GOT TuRNED UP loud...VERY loud! louder every day. The continuing mainstream exposure is helping propel us toward our goal of making FIRST known and recognized around the globe. -

NORTH Highland AVENUE

NORTH hIGhLAND AVENUE study December, 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Study Prepared by the City of Atlanta Department of Planning, Development and Neighborhood Conservation Bureau of Planning In conjunction with the North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force December 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force Members Mike Brown Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Warren Bruno Virginia Highlands Business Association Winnie Curry Virginia Highlands Civic Association Peter Hand Virginia Highlands Business Association Stuart Meddin Virginia Highlands Business Association Ruthie Penn-David Virginia Highlands Civic Association Martha Porter-Hall Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Jeff Raider Virginia Highlands Civic Association Scott Riley Virginia Highlands Business Association Bill Russell Virginia Highlands Civic Association Amy Waterman Virginia Highlands Civic Association Cathy Woolard City Council – District 6 Julia Emmons City Council Post 2 – At Large CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VISION STATEMENT Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 1:1 Purpose 1:1 Action 1:1 Location 1:3 History 1:3 The Future 1:5 Chapter 2 TRANSPORTATION OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 2:1 Introduction 2:1 Motorized Traffic 2:2 Public Transportation 2:6 Bicycles 2:10 Chapter 3 PEDESTRIAN ENVIRONMENT OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 3:1 Sidewalks and Crosswalks 3:1 Public Areas and Gateways 3:5 Chapter 4 PARKING OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 4:1 On Street Parking 4:1 Off Street Parking 4:4 Chapter 5 VIRGINIA AVENUE OPPORTUNITIES -

1 REMARKS by GEORGIA TECH PRESIDENT G. WAYNE CLOUGH Opening of Georgia Tech Hotel and Conference Center September 4, 2003 Thank

REMARKS BY GEORGIA TECH PRESIDENT G. WAYNE CLOUGH Opening of Georgia Tech Hotel and Conference Center September 4, 2003 Thank you, Susan (Hill). This is a very exciting day for us, as we mark the official opening of the Georgia Tech Hotel and Conference Center. After the Downtown Connector was built, separating Georgia Tech from Midtown Atlanta, the property where we are today deteriorated rapidly, and for many years it remained an eyesore of vacant lots and abandoned buildings. Then Georgia Tech made a strategic decision to purchase the land, and in conjunction with area businesses and the Midtown Alliance neighborhood organization, we developed a plan for its use. Even the city of Atlanta and the state of Georgia eventually became participants, especially in the ongoing effort to improve the Fifth Street Bridge, which, when it is completed, will transform this back door to the front door of Georgia Tech’s campus. Over the past three years, more than $300 million has been poured into the construction of a complex of buildings totaling more than 2.5 million square feet and lining either side of Fifth Street between the Connector and the Biltmore. Technology Square gathers Georgia Tech’s economic development resources in a place where our students, faculty, and staff can be incorporated into and contribute to the city’s economic heartbeat and help to drive the development of a signature technology corridor for Atlanta and Georgia. Technology Square also includes wide, pedestrian-friendly sidewalks and a number of retail outlets, anchored by Barnes & Noble @ Georgia Tech to serve our students, faculty, and staff and Midtown workers and residents alike. -

City of Atlanta 2016-2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Community Work Program (CWP)

City of Atlanta 2016-2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Community Work Program (CWP) Prepared By: Department of Planning and Community Development 55 Trinity Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30303 www.atlantaga.gov DRAFT JUNE 2015 Page is left blank intentionally for document formatting City of Atlanta 2016‐2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) and Community Work Program (CWP) June 2015 City of Atlanta Department of Planning and Community Development Office of Planning 55 Trinity Avenue Suite 3350 Atlanta, GA 30303 http://www.atlantaga.gov/indeex.aspx?page=391 Online City Projects Database: http:gis.atlantaga.gov/apps/cityprojects/ Mayor The Honorable M. Kasim Reed City Council Ceasar C. Mitchell, Council President Carla Smith Kwanza Hall Ivory Lee Young, Jr. Council District 1 Council District 2 Council District 3 Cleta Winslow Natalyn Mosby Archibong Alex Wan Council District 4 Council District 5 Council District 6 Howard Shook Yolanda Adreaan Felicia A. Moore Council District 7 Council District 8 Council District 9 C.T. Martin Keisha Bottoms Joyce Sheperd Council District 10 Council District 11 Council District 12 Michael Julian Bond Mary Norwood Andre Dickens Post 1 At Large Post 2 At Large Post 3 At Large Department of Planning and Community Development Terri M. Lee, Deputy Commissioner Charletta Wilson Jacks, Director, Office of Planning Project Staff Jessica Lavandier, Assistant Director, Strategic Planning Rodney Milton, Principal Planner Lenise Lyons, Urban Planner Capital Improvements Program Sub‐Cabinet Members Atlanta BeltLine, -

Offering Memorandum Charming Freestanding Office | Midtown Atlanta | ± 3,618 Sf T a B L E O F C O N T E N T S

OFFERING MEMORANDUM CHARMING FREESTANDING OFFICE | MIDTOWN ATLANTA | ± 3,618 SF T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Andy Lundsberg PROPERTY INFORMATION 3 Partner, Bull Realty [email protected] EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 404-876-1640 x107 PROPERTY INFORMATION 6 Michael Wess, CCIM PHOTOS 7 Partner, Bull Realty [email protected] FLOOR PLANS 12 404-876-1640 x150 AREA MAPS 13 Bull Realty, Inc. 50 Glenlake Parkway, Suite 600 IN THE AREA 15 Atlanta, GA 30328 16 BullRealty.com ABOUT THE AREA ATLANTA 17 ATLANTA TOP EMPLOYERS 18 BROKER PROFILES 19 DISCLAIMER 20 Exclusively listed by Bull Realty, Inc. C h a r m i n g F r e e s t a n d i n g O f f i c e | M i d t o w n A t l a n t a | ± 3 , 6 1 8 S F | P a g e 2 o f 2 0 P R O P E R T Y I N F O R M AT I O N C h a r m i n g F r e e s t a n d i n g O f f i c e | M i d t o w n A t l a n t a | ± 3 , 6 1 8 S F | P a g e 3 o f 2 0 C h a r m i n g F r e e s t a n d i n g O f f i c e | M i d t o w n A t l a n t a | ± 3 , 6 1 8 S F | P a g e 4 o f 2 0 E X E C U T I V E S U M M A R Y PROPERTY DESCRIPTION This charming, freestanding office features ± 3,618 SF which includes an ± 1,142 SF open finished & well-lit terrace level which is currently vacant. -

Subarea 1 Atlanta Beltline Master Plan

Atlanta BeltLine Master Plan SUBAREA 1 PLAN RECOMMENDATIONS REPORT Prepared for Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. by Tunnell-Spangler-Walsh & Associates with Grice & Associates, Inc. and Smith Dalia Architects Adopted by the Atlanta City Council on December 6, 2010 this page left intentionally blank this report has been formatted to be printed double-sided in an effort to save paper ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Honorable Mayor Kasim Reed The Honorable Kasim Reed, City of Atlanta Mayor The Honorable Joyce M. Shepherd, Atlanta City Council ATLANTA CITY COUNCIL District 12 Ceasar Mitchell, President John Somerhalder, AGL Resources, Chair of the Board, BeltLine Partnership Carla Smith, District 1 Subarea 1 Planning Committee Kwanza Hall, District 2 Michael Altermann, West End Mall Ivory Lee Young, Jr., District 3 Patrick Berry, Westview Cleta Winslow, District 4 Bakari Brooks, Atlanta Housing Authority Natalyn Mosby Archibong, District 5 Allean Brown, NPU S Liaison Alex Wan, District 6 Danielle Carney, NPU T Liaison Howard Shook, District 7 Ed Chang, KIPP Strive Yolanda Adrean, District 8 Jo Ann Chitty, Selig Enterprises Felicia A. Moore, District 9 Teeya Davis, Cleta Winslow’s Office C. T. Martin, District 10 Reverend Elligan Keisha Bottoms, District 11 Douglas Fitzgerald, Donnelly Gardens Apartments Joyce Sheperd, District 12 Vonda Henry, West End Michael Julian Bond, Post 1 at Large Deudishar Jenkins, Mimms Enterprises Aaron Watson, Post 2 at Large Herb Joseph, Atlanta Public Schools H. Lamar Willis, Post 3 at Large Nia Knowles, NPU T ATLANTA BELTLINE, INC. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Travie Leslie, NPU V Elizabeth B. Chandler, Chair Felicia Phillips, Oakland City Clara Axam, Vice Chair, Enterprise Community Partners, Inc.; Derek Roqumore, Outdoor Activity Center MARTA Board of Directors David Sitt (out of town participant), Kroger Citi Center Joseph A. -

Me07finalrevised.Pdf

THE ANNUAL REPORT OF THE George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering 2006-2007 LETTER FROM talented and enthusiastic new faculty members, most of them at the assistant professor level. We lost some faculty to retirement, others to THE CHAIR resignations, and others were recruited to other institutions. Marc Levenston went to Stanford. Chris Lynch went to the University of This will be the last Annual Report California at Los Angeles. Bill King went to the University of Illinois. under my watch as chair of the Tom Kurfess went to Clemson. Dan Baldwin went to industry. So the Woodruff School of Mechanical new faculty not only replaced those who left, but allowed us to grow to Engineering. As most of you know, I help match our faculty size to our enrollment, which has continued to announced last November my grow. Based on enrollment, we still need additional faculty and hope to intention to retire at the end of May add them in the coming year. We also graduated a record number of 2007. In the spring, I was feted with bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral students. As you will see in the several very nice going away parties. statistics presented in this report, not only is enrollment up, but student Some of my former Ph.D. students quality continues to improve. We have a very talented group of under- came from across the country and graduate and graduate students. overseas to participate in the celebrations. I was humbled by the honors Another significant change was the loss of our long term presented to me. -

Stac.Pdf (6.097Mb)

Postgraduate Education Ivan Allen College Because of STAC’s emphasis on research and writing, Literature, Communication, and Culture is one of six schools BACHELOR OFOF SCIENCESCIENCE ININ students are prepared to pursue advanced degrees. in the Ivan Allen College, which was established in 1990 as All STAC graduates complete a senior seminar or the liberal arts college of Georgia Tech. The others are SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, senior thesis, requirements that anticipate the work Economics; History, Technology, and Society; the Sam Nunn demanded of them in graduate school. Graduate School of International Affairs; Modern Languages; and programs in business, law, and medicine actively AND CULTURE Public Policy. recruit students with interdisciplinary training. Because STAC majors are interested in communication, Introspection STAC students have gone on to graduate programs science, and culture, many participate in campus in policy, law, journalism, medicine, education, and organizations, including: Atlanta Interaction literature at institutions including: Technique (Tech’s award-winning, student-run newspaper) A lively city with a population of more than 4 million, Boston University • Innovation Blueprint (yearbook staff) Atlanta offers many cultural and economic opportunities. Columbia University • DramaTech (the student-run theater) Georgia Tech’s 400-acre campus is located in the heart of University of California, Berkeley • Campus Life The STAC Society (a student-faculty group that the city, near the High Museum, the Carter Center, the King University of Chicago • organizes social events and professional development) Center, CNN, and Turner Field. Students are encouraged to University of Georgia Ivan Allen College Student Advisory Board supplement their academic education with the resources University of Tennessee • • Center for Study of Women, Science, and Technology (WST) available in this major urban center. -

Tech Square Birth of an Innovation District

Tech Square Birth of an Innovation District Chris Downing, P.E. Vice President Enterprise Innovation Institute Tech Square Today A uniform mix of economic, physical and networking assets Georgia Tech Square Tech Downtown Atlanta Georgia Tech Square Tech Tech Square TECH SQUARE TODAY • 1.4 million square feet of office, research, retail, and hotel space • Scheller Business School and GT Global Learning Center • 2014 Outstanding Research Park Award winner, Association of University Research Parks • 100+ technology startups and three accelerator programs • 20 Corporate Innovation Centers including Southern Company, Panasonic, and Home Depot BIRTH OF AN INNOVATION DISTRICT In 2000, the roughly 13-acre area now known as Tech Square and anchored by Spring and Fifth streets, was little more than a collection of surface lots. The Georgia Tech Foundation invested $180 million to create campus facilities and commercial space, and partnered with The University Financing Foundation, and Gateway Development Services to create the entrepreneurial and economic hub that is Tech Square. Tech Square An innovation district where new start-up ventures, large companies, and higher education collaborate to develop new technologies and impact economic development. Tech Square BREAKTHROUGH BREAKTHROUGH BREAKTHROUGH TALENT IDEAS COMPANIES Advanced Technology Development TechSquare Labs Center (ATDC) VentureLab Flashpoint Accelerator 100+ Technology Startup Companies The Garage 20 Corporate Innovation Centers, Georgia Tech Hotel and Conference including Anthem, Panasonic, Home Center Depot, AT&T Foundry, & Delta Air Lines Global Learning Center NCR Global Headquarters (under Georgia Tech Research Institute construction) Scheller College of Business Coda (under construction) Tech Square Research Building TECH SQUARE TIMELINE 1997 GT Foundation Purchases Land 2000 President Wayne Clough announces Technology Square project. -

GEORGIA TECH FOUNDATION, INC. Consolidated Financial Statements June 30, 2018 and 2017 (With Independent Auditors’ Report Thereon) GEORGIA TECH FOUNDATION, INC

GEORGIA TECH FOUNDATION, INC. Consolidated Financial Statements June 30, 2018 and 2017 (With Independent Auditors’ Report Thereon) GEORGIA TECH FOUNDATION, INC. Table of Contents Page(s) Independent Auditors’ Report 1 Consolidated Financial Statements: Consolidated Statements of Financial Position 2 Consolidated Statements of Activities 3 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows 4 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements 5–37 KPMG LLP Suite 2000 303 Peachtree Street, N.E. Atlanta, GA 30308-3210 Independent Auditors’ Report The Board of Trustees Georgia Tech Foundation, Inc.: We have audited the accompanying consolidated financial statements of Georgia Tech Foundation, Inc. and its subsidiaries, which comprise the consolidated statements of financial position as of June 30, 2018 and 2017, and the related consolidated statements of activities and cash flows for the years then ended, and the related notes to the consolidated financial statements. Management’s Responsibility for the Consolidated Financial Statements Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these consolidated financial statements in accordance with U.S. generally accepted accounting principles; this includes the design, implementation, and maintenance of internal control relevant to the preparation and fair presentation of consolidated financial statements that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error. Auditors’ Responsibility Our responsibility is to express an opinion on these consolidated financial statements based on our audits. We conducted our audits in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the consolidated financial statements are free from material misstatement. -

Layout 1 (Page 1)

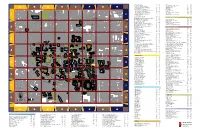

Hopkins Warehouse 184 B-6 Coliseum 73 F-4 Howey Physics Building 81 D-5 Edge Intercollegiate Athletic Center 18 F-7 Industrial and Systems Engineering Georgia Tech Water Sports 97 C-4 A BDC E FHG (Groseclose Building and ISYE Annex) 56 C-6 Glenn Softball Field 365 D-1 Institute of Paper Science and Technology 129 C-4 Grant Field 355 F-7 KIOSK VIEW PORT Instructional Center 55 C-6 Griffin Track 342 E-4 International Affairs and Public Policy 137 C-6 Luck Building 73A F-4 365 Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts (781 Marietta St.) 137 C-6 Moore Tennis Center 80 F-4 Klaus Advanced Computing Building 153 E-5 O’Keefe Gym 33A F-4 Knight Building (Aerospace Engineering) 101 E-7 Rice Center for Sports Performance 18A F-7 LeCraw Auditorium (Management Building) 172 G-6 Rose Bowl Field 347 F-4 Library and Information Center 77 E-6 Stamps Field 348 C-5 1 1 Literature, Communication, and Culture Tennis Center (Moore Tennis Center) 80 F-4 (Skiles Building) 2 E-7 Love Manufacturing Building 144 C-5 850 Management, College of 172 G-6 RELIGIOUS ORGANIZATIONS FOU RTEENTH STREET Manufacturing Related Disciplines Complex (MRDC) 135 D-5 ID# Grid Manufacturing Research Center (MARC) 126 C-5 Baptist Student Union 339 F-6 FOURTEENTH STREET Mason Building (Civil Engineering) 111 D-5 Campus Christian Federation 332 F-6 Materials Science and Engineering 144 C-5 Catholic Center 341 F-6 Mathematics (Skiles Building) 2 E-7 Lutheran Center 343 F-5 141 Mechanical Engineering 135 D-5 Methodist Center (Wesley Foundation) 344 F-6 Mechanical Engineering Research Building -

Student Catalog (2017-2018)

Welcome to West Georgia Technical College!| 1 2| West Georgia Technical College Student Catalog 2017-2018 Welcome to West Georgia Technical College! Dear Student, Welcome to West Georgia Technical College! Our team is dedicated to helping you achieve your highest potential in technical education and career advancement. Whether you are looking to advance in your current job or gain the skills for an entirely new career field, West Georgia Tech offers over 120 associate degree, diploma and technical certificate programs of study that prepare you to excel in today’s technically advanced, global economy. At West Georgia Tech, the focus is on student success and workforce development that enhances our communities. We offer flexible class schedules, multiple campus locations and the latest in technology to provide our students a superior learning environment. Our students enjoy clubs, organizations and activities and a range of NJCAA athletic programs to help them grow inside and outside the classroom. Our dedicated faculty and staff are committed to providing a fulfilling and satisfying learning experience through the highest quality instruction and customer service. We also value our numerous partnerships with area business and industry, and we offer excellent continuing education and economic development programs to further support the workforce development needs of this region. Please visit any of our locations in Carroll, Coweta, Douglas, Haralson, Heard, Meriwether and Troup counties to experience firsthand our collegiate atmosphere and student centered environment. We look forward to serving you as a premier College within the Technical College System of Georgia! I wish you continued success in all your educational endeavors and future career goals.