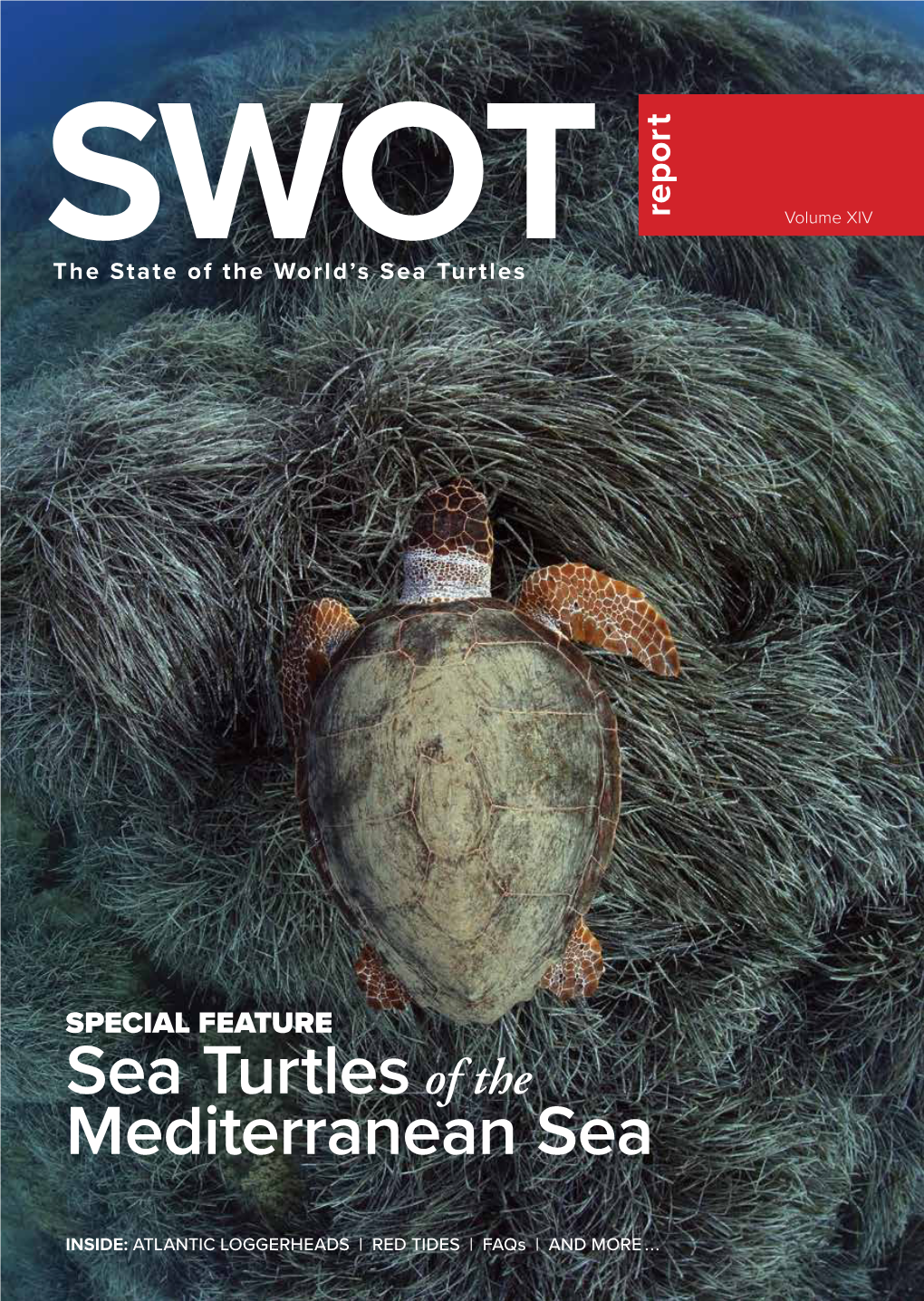

SWOT: SPECIAL FEATURE Sea Turtles of the Mediterranean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyprus Tourism Organisation Offices 108 - 112

CYPRUS 10000 years of history and civilisation CONTENTS CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 CYPRUS 10000 years of history and civilisation 6 THE HISTORY OF CYPRUS 8200 - 1050 BC Prehistoric Age 7 1050 - 480 BC Historic Times: Geometric and Archaic Periods 8 480 BC - 330 AD Classical, Hellenistic and Roman Periods 9 330 - 1191 AD Byzantine Period 10 - 11 1192 - 1489 AD Frankish Period 12 1489 - 1571 AD The Venetians in Cyprus 13 1571 - 1878 AD Cyprus becomes part of the Ottoman Empire 14 1878 - 1960 AD British rule 15 1960 - today The Cyprus Republic, the Turkish invasion, 16 European Union entry LEFKOSIA (NICOSIA) 17 - 36 LEMESOS (LIMASSOL) 37 - 54 LARNAKA 55 - 68 PAFOS 69 - 84 AMMOCHOSTOS (FAMAGUSTA) 85 - 90 TROODOS 91 - 103 ROUTES Byzantine route, Aphrodite Cultural Route 104 - 105 MAP OF CYPRUS 106 - 107 CYPRUS TOURISM ORGANISATION OFFICES 108 - 112 3 LEFKOSIA - NICOSIA LEMESOS - LIMASSOL LARNAKA PAFOS AMMOCHOSTOS - FAMAGUSTA TROODOS 4 INTRODUCTION Cyprus is a small country with a long history and a rich culture. It is not surprising that UNESCO included the Pafos antiquities, Choirokoitia and ten of the Byzantine period churches of Troodos in its list of World Heritage Sites. The aim of this publication is to help visitors discover the cultural heritage of Cyprus. The qualified personnel at any Information Office of the Cyprus Tourism Organisation (CTO) is happy to help organise your visit in the best possible way. Parallel to answering questions and enquiries, the Cyprus Tourism Organisation provides, free of charge, a wide range of publications, maps and other information material. Additional information is available at the CTO website: www.visitcyprus.com It is an unfortunate reality that a large part of the island’s cultural heritage has since July 1974 been under Turkish occupation. -

Marine Turtle Research and Conservation in Libya

Marine TurTle research and conservaTion in libya a conTribuTion To safeguarding MediTerranean biodiversiTy legal notice: The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Specially Protected Areas Regional Activity Centre (SPA/RAC) and United Nations Environment Programme / Mediterranean Action Plan (UNEP/MAP) concerning the legal status of any State, Territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of their frontiers or boundaries. copyright: All property rights of texts and content of different types of this publication belong to SPA/RAC. Reproduction of these texts and contents, in whole or in part, and in any form, is prohibited without prior written permission from SPA/RAC, except for educational and other non-commercial purposes, provided that the source is fully acknowledged. © 2021 united nations environment Programme Mediterranean action Plan specially Protected areas regional activity centre Boulevard du Leader Yasser Arafat B.P.337 - 1080 Tunis Cedex – TUNISIA [email protected] for bibliographic purposes, this volume may be cited as: SPA/RAC-UNEP/MAP, 2021. Marine Turtle Research and Conservation in Libya: A contribution to safeguarding Mediterranean Biodiversity. By Abdulmaula Hamza. Ed. SPA/RAC, Tunis: pages 77. cover photo credit: sPa/rac, artescienza copyright of the photos: libsTP The present report has been prepared in the framework of the Marine Turtles project fnanced by MAVA. For more information: www-spa-rac.org Marine Turtle Research and Conservation in Libya A contribution to safeguarding Mediterranean Biodiversity Study required and fnanced by: Specially Protected Areas Regional Activity Centre (SPA/RAC) Boulevard du Leader Yasser Arafat B.P. -

CRUISES-DIVING 23/4/2014 10:24 Πμ Page 29

MAY-JUN 027-031_ORGANIZED-CRUISES-DIVING 23/4/2014 10:24 πμ Page 29 • CRUISES 1-day Cruises 3-day Cruises 6 GREEK ISLANDS & ISTANBUL Istanbul SARONIC GULF 4 GREEK ISLANDS & TURKEY (WEEKEND) March 14 - October 24 on Fridays Cruise company: Louis Cruises Cruise ship: LOUIS OLYMPIA Dep 11:00 from Piraeus , Arr 06:00 at Piraeus TURKEY Chios Ports of call : Mykonos, Kusadasi (Ephesus), Patmos, Crete (Heraklion), Santorini Kusadasi Lavrio Piraeus Mykonos IDYLLIC AEGEAN (WEEKDAYS) Egina Symi July04 - August29 on Fridays Santorini Rodos Cruise company: Louis Cruises Poros Cruise ship: LOUIS OLYMPIA Hydra Dep 11:00 from Piraeus , Arr 06:30 at Lavrion Agios Nikolaos Ports of call: Mykonos, Kusadasi (Ephesus), Samos, Milos April25 - June20 on Fridays September05 - October 24 on Fridays Cruise company: Louis Cruises Daily, all year round Cruise ship: LOUIS CRISTAL Cruise company: Hydraiki Naval Company 4-day Cruises Dep 12:00 from Lavrion , Arr 06:00 at Lavrion Cruise ships: ANNA MAROU, PLATYTERA Ports of call: Istanbul, Kusadasi (Ephesus), Dep 08:00 from Flisvos Santorini, Crete (Agios Nikolaos), Rhodes, Symi, Ports of call: Egina, Poros, Hydra 5 GREEK ISLANDS & TURKEY Chios, Mykonos Daily, all year round Cruise company: Olympic Cruises Cruise ship: KASSANDRA DELPHINOUS ADRIATIC EXPLORER Dep 08:00 from Flisvos , Arr 20:00 at Flisvos Ports of call: Hydra, Poros, Egina North Aegean Ionian Islands Turkey Islands Central Greece KERKYRA - IONIAN ISLANDS Piraeus Kussadasi Mykonos Patmos Ionian Kerkyra Sea Santorini Rhodos Heraklion Crete Plataria Syvota -

Albo04112020.Pdf

COLLEGIO PROVINCIALE GEOMETRI E GEOMETRI LAUREATI DI SALERNO DI SALERNO Elenco dei professionisti iscritti all'Albo Situazione al 04/11/2020 Stampato in data: 04/11/2020 STATO COGNOME E NOME CORRISPONDENZA DIPLOMA MATR. DATA E LUOGO DI NASCITA DATA ISCR. CODICE FISCALE ESAME DI STATO Iscritto Albo ABATE ANDREA VITTORIO VENETO, 184 CAVA DE' TIRRENI 84013 SA cava dei tirreni - 2000 4760 12/12/1979 CAVA DE' TIRRENI 18/02/2008 SALERNO - 2005 Iscritto Albo ABATE ANIELLO VIALE G. VERDI, LOTTO 1 SCALA F INERNO 4 SALERNO 84131 SA Montesano sulla Marcellana - 2006 4868 12/09/1960 SAN MARTINO VALLE CAUDINA 06/05/2009 SALERNO - 2008 Iscritto Albo ABATE ANNA MARIA PEZZE DELLA CORTE,30 SAN GREGORIO MAGNO 84020 SA CASAMICCIOLA - 1978 4274 25/09/1957 BARANO D'ISCHIA 05/04/2002 Iscritto Albo ABATE ANTONELLO QUINTINO DI VONA, 11 SALERNO 84100 SA nola - 2002 4684 21/09/1983 SALERNO 29/01/2007 SALERNO - 2006 Iscritto Albo ABATE ARMANDO VIA SANT'ANNA N° 57/B GIFFONI SEI CASALI 84090 SA SALERNO - 2016 5327 07/09/1997 SALERNO 27/05/2020 SALERNO - 2019 Iscritto Albo ABATE GABRIELLA VIA SANDRO PERTINI N. 6 PONTECAGNANO FAIANO 84098 SA SALERNO - 2016 5301 18/05/1997 BATTIPAGLIA 23/01/2019 SALERNO - ANNO 2018 Iscritto Albo ABATE GIOVANNI VIA DEL TACCARO, 102 ANGRI 84012 SA Cava de' Tirreni - 2017 5330 08/08/1998 NOCERA INFERIORE 09/09/2020 SALERNO - 2019 Iscritto Albo ABATE GIUSEPPE VIA EUROPA,107 PONTECAGNANO 84098 SA Salerno - 1978 2501 31/01/1959 PONTECAGNANO 26/05/1981 Iscritto Albo ABATE GIUSEPPE VIA ARTURO CAPONE,9 SALERNO 84126 SA NOLA - 1999 5157 23/01/1980 SALERNO 10/03/2014 SALERNO - ANNO 2012 Iscritto Albo ABATE GIUSEPPE VIA DEL TACCARO 102 ANGRI 84012 SA CAVA DE TIRRENI - 1990 4519 01/05/1971 SALERNO 23/05/2005 SALERNO - 1998 Iscritto Albo ABATE LEONZIO VIA POZZILLO, 11 POLICASTRO BUSSENTINO 84067 SA SAPRI - 1995 4258 04/05/1976 MARATEA 25/02/2002 Iscritto Albo ABATE MARINO VIA S. -

Data Structure

Data structure – Water The aim of this document is to provide a short and clear description of parameters (data items) that are to be reported in the data collection forms of the Global Monitoring Plan (GMP) data collection campaigns 2013–2014. The data itself should be reported by means of MS Excel sheets as suggested in the document UNEP/POPS/COP.6/INF/31, chapter 2.3, p. 22. Aggregated data can also be reported via on-line forms available in the GMP data warehouse (GMP DWH). Structure of the database and associated code lists are based on following documents, recommendations and expert opinions as adopted by the Stockholm Convention COP6 in 2013: · Guidance on the Global Monitoring Plan for Persistent Organic Pollutants UNEP/POPS/COP.6/INF/31 (version January 2013) · Conclusions of the Meeting of the Global Coordination Group and Regional Organization Groups for the Global Monitoring Plan for POPs, held in Geneva, 10–12 October 2012 · Conclusions of the Meeting of the expert group on data handling under the global monitoring plan for persistent organic pollutants, held in Brno, Czech Republic, 13-15 June 2012 The individual reported data component is inserted as: · free text or number (e.g. Site name, Monitoring programme, Value) · a defined item selected from a particular code list (e.g., Country, Chemical – group, Sampling). All code lists (i.e., allowed values for individual parameters) are enclosed in this document, either in a particular section (e.g., Region, Method) or listed separately in the annexes below (Country, Chemical – group, Parameter) for your reference. -

KING of the RING – Muay Thai Rules

WIPU – World independent Promoters Union in association with worldwide promoters, specialized magazines & TV p r e s e n t s WORLD INDEPENDANT ORIENTAL PRO BOXING & MMA STAR RANKINGS OPEN SUPER HEAVYWEIGHT +105 kg ( +232 lbs ) KING OF THE RING – full Muay Thai rules 1. Semmy '' HIGH TOWER '' Schilt ( NL ) = 964 pts LLOYD VAN DAMS ( NL ) = 289 pts 2. Peter '' LUMBER JACK '' Aerts ( NL ) = 616 pts Venice ( ITA ), 29.05.2004. 3. Alistar Overeem ( NL ) = 524 pts KING OF THE RING – Shoot boxing rules 4. Jerome '' GERONIMO '' Lebanner ( FRA ) = 477 pts - 5. Alexei '' SCORPION '' Ignashov ( BLR ) = 409 pts KING OF THE RING – Thai boxing rules 6. Anderson '' Bradock '' Silva ( BRA ) = 344 pts TONY GREGORY ( FRA ) = 398 pts 7. '' MIGHTY MO '' Siligia ( USA ) = 310 pts Auckland ( NZ ), 09.02.2008. 8. Daniel Ghita ( ROM ) = 289 pts KING OF THE RING – Japanese/K1 rules 9. Alexandre Pitchkounov ( RUS ) = 236 pts - 10. Mladen Brestovac ( CRO ) = 232 pts KING OF THE RING – Oriental Kick rules 11. Bjorn '' THE ROCK '' Bregy ( CH ) = 231 pts STIPAN RADIĆ ( CRO ) = 264 pts 12. Konstantins Gluhovs ( LAT ) = 205 pts Johanesburg ( RSA ), 14.10.2006. 13. Rico Verhoeven ( NL ) = 182 pts Upcoming fights 14. Peter '' BIG CHIEF '' Graham ( AUS ) = 177 pts 15. Ben Edwards ( AUS ) = 161 pts 16. Patrice Quarteron ( FRA ) = 147 pts 17. Patrick Barry ( USA ) = 140 pts 18. Mark Hunt ( NZ ) = 115 pts 19. Paula Mataele ( NZ ) = 105 pts 20. Fabiano Goncalves ( BRA ) = 89 pts WIPU – World independent Promoters Union in association with worldwide promoters, specialized magazines & TV p r e s e n t s WORLD INDEPENDANT ORIENTAL PRO BOXING & MMA STAR RANKINGS HEAVYWEIGHT – 105 kg ( 232 lbs ) KING OF THE RING – full Muay Thai rules CHEIK KONGO (FRA) = 260 pts 1. -

DESERTMED a Project About the Deserted Islands of the Mediterranean

DESERTMED A project about the deserted islands of the Mediterranean The islands, and all the more so the deserted island, is an extremely poor or weak notion from the point of view of geography. This is to it’s credit. The range of islands has no objective unity, and deserted islands have even less. The deserted island may indeed have extremely poor soil. Deserted, the is- land may be a desert, but not necessarily. The real desert is uninhabited only insofar as it presents no conditions that by rights would make life possible, weather vegetable, animal, or human. On the contrary, the lack of inhabitants on the deserted island is a pure fact due to the circumstance, in other words, the island’s surroundings. The island is what the sea surrounds. What is de- serted is the ocean around it. It is by virtue of circumstance, for other reasons that the principle on which the island depends, that the ships pass in the distance and never come ashore.“ (from: Gilles Deleuze, Desert Island and Other Texts, Semiotext(e),Los Angeles, 2004) DESERTMED A project about the deserted islands of the Mediterranean Desertmed is an ongoing interdisciplina- land use, according to which the islands ry research project. The “blind spots” on can be divided into various groups or the European map serve as its subject typologies —although the distinctions are matter: approximately 300 uninhabited is- fluid. lands in the Mediterranean Sea. A group of artists, architects, writers and theoreti- cians traveled to forty of these often hard to reach islands in search of clues, impar- tially cataloguing information that can be interpreted in multiple ways. -

Saviours of the Seas Cruise the World

June 2020 boatinternational.com / £7.00 THE OCEANS ISSUE MISSION TO A CORAL SAVIOURS KINGDOM OF THE SEAS MEET THE WINNERS OF OUR 2020 OCEAN AWARDS CRUISE THE WORLD Oyster’s elegant new flagship is built for blue water At the helm of 43-metre Ultimate Greek island guide. How to build the world’s biggest Canova: the new foiling Don’t set course until you’ve sailing catamaran – and then wonder from Baltic Yachts read our essential feature turn it into a floating gallery VOYAGE Right: an Ancient Roman theatre built around the third century BCE; Right, middle: the white cliffs on Sarakiniko Beach. Below: octopuses hung out to dry in the village of WHICH Mandrakia Milos THE VIBE: This volcanic island may lack the razzmatazz of some of its better-known Cycladic neighbours, but with fewer crowds and more beaches than any other island in the group, GREEK it shouldn’t be ignored. It’s not the place if you want to party next to Paris Hilton but its spectacular rock formations, hot springs and stunning cliffs make it a geography buff’s nirvana. WHO GOES? Celebrity visitors are few and far between (thankfully this also means no hordes of Instagram influencer ISLAND wannabes) but superyacht royalty, including the late Steve Jobs’ Venus, are regularly spotted off its shores. LOCAL LOWDOWN: Milos’s mineral extraction industry dates from the Neolithic period and today it is still the biggest supplier of bentonite and perlite in the European Union. Its SUITS traditional mining industry is why the island has been slower to develop its tourism trade, but its mineral-rich grounds are also what make it so spectacular. -

Readingsample

The TRANSMED Atlas. The Mediterranean Region from Crust to Mantle Geological and Geophysical Framework of the Mediterranean and the Surrounding Areas Bearbeitet von William Cavazza, François M. Roure, Wim Spakman, Gerard M. Stampfli, Peter A. Ziegler 1. Auflage 2004. Buch. xxiii, 141 S. ISBN 978 3 540 22181 4 Format (B x L): 19,3 x 27 cm Gewicht: 660 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Physik, Astronomie > Angewandte Physik > Geophysik Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Chapter 1 The Mediterranean Area and the Surrounding Regions: Active Processes, Remnants of Former Tethyan Oceans and Related Thrust Belts William Cavazza · François Roure · Peter A. Ziegler Abstract 1.1 Introduction The Mediterranean domain provides a present-day geo- From the pioneering studies of Marsili – who singlehand- dynamic analog for the final stages of a continent-conti- edly founded the field of oceanography with the publi- nent collisional orogeny. Over this area, oceanic lithos- cation in 1725 of the Histoire physique de la mer, a scien- pheric domains originally present between the Eurasian tific best-seller of the time (Sartori 2003) – to the tech- and African-Arabian plates have been subducted and par- nologically most advanced cruises of the R/V JOIDES tially obducted, except for the Ionian basin and the south- Resolution, the Mediterranean Sea has represented a cru- eastern Mediterranean. -

Eoa Kai Esperia

Eoa kai Esperia Vol. 7, 2007 ΠΑΡΓΑ, ΠΡΕΒΕΖΑ, ΒΟΝΙΤΣΑ: ΑΣΤΙΚΕΣ ΣΥΣΣΩΜΑΤΩΣΕΙΣ ΣΤΑ ΒΕΝΕΤΙΚΑ ΗΠΕΙΡΩΤΙΚΑ ΕΞΑΡΤΗΜΑΤΑ ΠΑΠΑΚΩΣΤΑ ΧΡΙΣΤΙΝΑ https://doi.org/10.12681/eoaesperia.91 Copyright © 2007 To cite this article: ΠΑΠΑΚΩΣΤΑ, (2007). ΠΑΡΓΑ, ΠΡΕΒΕΖΑ, ΒΟΝΙΤΣΑ: ΑΣΤΙΚΕΣ ΣΥΣΣΩΜΑΤΩΣΕΙΣ ΣΤΑ ΒΕΝΕΤΙΚΑ ΗΠΕΙΡΩΤΙΚΑ ΕΞΑΡΤΗΜΑΤΑ. Eoa kai Esperia, 7, 213-232. doi:https://doi.org/10.12681/eoaesperia.91 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 03/10/2021 20:48:57 | ΧΡΙΣΤΙΝΑ Ε. ΠΑΠΑΚΩΣΤΑ ΕΩΑ ΚΑΙ ΕΣΠΕΡΙΑ 7 (2007) ΠΑΡΓΑ, ΠΡΕΒΕΖΑ, ΒΟΝΙΤΣΑ: ΑΣΤΙΚΕΣ ΣΥΣΣΩΜΑΤΩΣΕΙΣ ΣΤΑ ΒΕΝΕΤΙΚΑ ΗΠΕΙΡΩΤΙΚΑ ΕΞΑΡΤΗΜΑΤΑ* Ι. Οι πηγές Αντικείμενο της έρευνας μου στο πλαίσιο του προγράμματος ΠΥΘΑΓΟ ΡΑΣ II, με θέμα «Ελληνικές Κοινότητες και Ευρωπαϊκός Κόσμος (13ος-19ος αι.). Μορφές αυτοδιοίκησης, κοινωνική οργάνωση, συγκρότηση ταυτοτή των», αποτέλεσε η ανασύνθεση της ιστορίας των αστικών συσσωματώσεων που συγκροτήθηκαν στις βενετοκρατούμενες περιοχές της Πάργας (15ος αιώνας), της Πρέβεζας και της Βόνιτσας (18ος αιώνας), μέσα από στοιχεία που συγκεντρώθηκαν από το Κρατικό Αρχείο της Βενετίας και τις βιβλιο θήκες της πόλης. Για την ανασύνθεση της ιστορίας της Κοινότητας της Πάργας κατ' αρχάς κρίθηκε σκόπιμο να μελετηθεί και να αποδελτιωθεί το έργο του Ludwig Salvator, Parga, die Seestadt im Epirus\ το οποίο εκδόθηκε στις αρχές του 20ού αιώνα. Στο έργο αυτό δημοσιεύεται αρχειακό υλικό, το οποίο απόκει ται κυρίως στο Αρχείο του νομού Κέρκυρας και μέχρι σήμερα έχει παραμεί νει ανεκμετάλλευτο. Επιπλέον, το γεγονός ότι δεν έχει σωθεί ο καταστατικός χάρτης της Κοινότητας κατέστησε αναγκαίο να μελετηθούν τα κείμενα των πρεσβειών, που η πόλη της Πάργας κατά καιρούς απέστειλε στην κεντρική βενετική διοίκηση, καθώς και στους ανώτερους βενετούς αξιωματούχους * Η παρούσα μελέτη υλοποιήθηκε στο πλαίσιο του υποέργου «Ελληνικές Κοινότητες και Ευρωπαϊκός Κόσμος (13ος-19ος αι.). -

The Abandonment of Butrint: from Venetian Enclave to Ottoman

dining in the sanctuary of demeter and kore 1 Hesperia The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens Volume 88 2019 Copyright © American School of Classical Studies at Athens, originally pub- lished in Hesperia 88 (2019), pp. 365–419. This offprint is supplied for per- sonal, non-commercial use only, and reflects the definitive electronic version of the article, found at <https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2972/hesperia.88.2.0365>. hesperia Jennifer Sacher, Editor Editorial Advisory Board Carla M. Antonaccio, Duke University Effie F. Athanassopoulos, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Angelos Chaniotis, Institute for Advanced Study Jack L. Davis, University of Cincinnati A. A. Donohue, Bryn Mawr College Jan Driessen, Université Catholique de Louvain Marian H. Feldman, University of California, Berkeley Gloria Ferrari Pinney, Harvard University Thomas W. Gallant, University of California, San Diego Sharon E. J. Gerstel, University of California, Los Angeles Guy M. Hedreen, Williams College Carol C. Mattusch, George Mason University Alexander Mazarakis Ainian, University of Thessaly at Volos Lisa C. Nevett, University of Michigan John H. Oakley, The College of William and Mary Josiah Ober, Stanford University John K. Papadopoulos, University of California, Los Angeles Jeremy B. Rutter, Dartmouth College Monika Trümper, Freie Universität Berlin Hesperia is published quarterly by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Founded in 1932 to publish the work of the American School, the jour- nal now welcomes submissions -

COLLEGIO PROVINCIALE GEOMETRI E GEOMETRI LAUREATI DI SALERNO DI SALERNO Elenco Dei Professionisti Iscritti All'albo

COLLEGIO PROVINCIALE GEOMETRI E GEOMETRI LAUREATI DI SALERNO DI SALERNO Elenco dei professionisti iscritti all'Albo Situazione al 20/10/2020 Stampato in data: 20/10/2020 STATO COGNOME E NOME CORRISPONDENZA DIPLOMA MATR. DATA E LUOGO DI NASCITA DATA ISCR. CODICE FISCALE ESAME DI STATO Iscritto Albo ABATE ANDREA VITTORIO VENETO, 184 CAVA DE' TIRRENI 84013 SA cava dei tirreni - 2000 4760 12/12/1979 CAVA DE' TIRRENI 18/02/2008 SALERNO - 2005 Iscritto Albo ABATE ANIELLO VIALE G. VERDI, LOTTO 1 SCALA F INERNO 4 SALERNO 84131 SA Montesano sulla Marcellana - 2006 4868 12/09/1960 SAN MARTINO VALLE CAUDINA 06/05/2009 SALERNO - 2008 Iscritto Albo ABATE ANNA MARIA PEZZE DELLA CORTE,30 SAN GREGORIO MAGNO 84020 SA CASAMICCIOLA - 1978 4274 25/09/1957 BARANO D'ISCHIA 05/04/2002 Iscritto Albo ABATE ANTONELLO QUINTINO DI VONA, 11 SALERNO 84100 SA nola - 2002 4684 21/09/1983 SALERNO 29/01/2007 SALERNO - 2006 Iscritto Albo ABATE ARMANDO VIA SANT'ANNA N° 57/B GIFFONI SEI CASALI 84090 SA SALERNO - 2016 5327 07/09/1997 SALERNO 27/05/2020 SALERNO - 2019 Iscritto Albo ABATE GABRIELLA VIA SANDRO PERTINI N. 6 PONTECAGNANO FAIANO 84098 SA SALERNO - 2016 5301 18/05/1997 BATTIPAGLIA 23/01/2019 SALERNO - ANNO 2018 Iscritto Albo ABATE GIOVANNI VIA DEL TACCARO, 102 ANGRI 84012 SA Cava de' Tirreni - 2017 5330 08/08/1998 NOCERA INFERIORE 09/09/2020 SALERNO - 2019 Iscritto Albo ABATE GIUSEPPE VIA EUROPA,107 PONTECAGNANO 84098 SA Salerno - 1978 2501 31/01/1959 PONTECAGNANO 26/05/1981 Iscritto Albo ABATE GIUSEPPE VIA ARTURO CAPONE,9 SALERNO 84126 SA NOLA - 1999 5157 23/01/1980 SALERNO 10/03/2014 SALERNO - ANNO 2012 Iscritto Albo ABATE GIUSEPPE VIA DEL TACCARO 102 ANGRI 84012 SA CAVA DE TIRRENI - 1990 4519 01/05/1971 SALERNO 23/05/2005 SALERNO - 1998 Iscritto Albo ABATE LEONZIO VIA POZZILLO, 11 POLICASTRO BUSSENTINO 84067 SA SAPRI - 1995 4258 04/05/1976 MARATEA 25/02/2002 Iscritto Albo ABATE MARINO VIA S.