HRD-87-66 Social Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

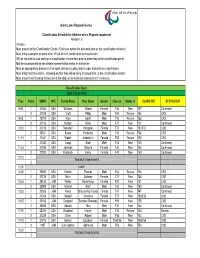

PI Classification Schedule GLRG.Xlsx

Great Lakes Regional Games Classification Schedule for Athletes with a Physical Impairment Version 1.6 Athletes - Must present to the Classification Centre 15 minutes before the allocated time on the classification schedule. Must bring a passport or some other official form of identification to classification. Will be required to read and sign a classification release form prior to presenting to the classification panel. May be accompanied by one athlete representative and/or an interpreter. Must be appropriately dressed in their sport clothes including shorts under tracksuits and sport shoes. Must bring their track chairs, strapping etc that they will be using in competition, to the classification session. Must ensure their throwing frames are at the stadium for technical assessments if necessary. Classification Day 1 Date: 9 June 2016 Time Panel SDMS NPC Family Name First Name Gender Class In Status In CLASS OUT STATUS OUT 9:00 1 31066 USA Williams Taleah Female T46 New T47 Confirmed 2 31008 USA Croft Philip Male T54 Review T54 CRS 9:45 1 15912 USA Rigo Isaiah Male T53 Review T53 CRS 2 31016 USA Nelson Brian Male F37 New F37 Confirmed 10:30 1 31218 USA Beaudoin Margaret Female T37 New T37/F37 CNS 2 30821 USA Evans Frederick Male T34 Review F34 CRS 11:15 1 11241 USA Weber Amberlynn Female T53 Review T53 CRS 2 31330 USA Langi Siale Male F43 New F43 Confirmed 11:45 1 31098 USA Johnson Shayna Female T44 New T44 Confirmed 2 27200 USA Frederick Emily Female F40 New F40 Confirmed 12:15 1 Technical Assessments 2 13:00 Lunch 14:00 1 20880 USA -

VMAA-Performance-Sta

Revised June 18, 2019 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veteran Monthly Assistance Allowance for Disabled Veterans Training in Paralympic and Olympic Sports Program (VMAA) In partnership with the United States Olympic Committee and other Olympic and Paralympic entities within the United States, VA supports eligible service and non-service-connected military Veterans in their efforts to represent the USA at the Paralympic Games, Olympic Games and other international sport competitions. The VA Office of National Veterans Sports Programs & Special Events provides a monthly assistance allowance for disabled Veterans training in Paralympic sports, as well as certain disabled Veterans selected for or competing with the national Olympic Team, as authorized by 38 U.S.C. 322(d) and Section 703 of the Veterans’ Benefits Improvement Act of 2008. Through the program, VA will pay a monthly allowance to a Veteran with either a service-connected or non-service-connected disability if the Veteran meets the minimum military standards or higher (i.e. Emerging Athlete or National Team) in his or her respective Paralympic sport at a recognized competition. In addition to making the VMAA standard, an athlete must also be nationally or internationally classified by his or her respective Paralympic sport federation as eligible for Paralympic competition. VA will also pay a monthly allowance to a Veteran with a service-connected disability rated 30 percent or greater by VA who is selected for a national Olympic Team for any month in which the Veteran is competing in any event sanctioned by the National Governing Bodies of the Olympic Sport in the United State, in accordance with P.L. -

Claudia Jones Part 5 of 10

92 FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION CLAUDIA JONES PART 2 OF 4 FILE NUMBER : 100-72390 '_._.1-- L/400//? 92/0/ 5 / I/01,0/WE i.___ .'?lé ,1v¬ I " ' -- -1. " r=-.~ ~ A 7 32,- *-¢4 --4 , _-._' V. 1 _@~_.._ ------ ' A-7 -,.-.e_...____ $__ .-:1 ¢ -_92 ., _! "-92*,':.,=...'_,r - ti ;=w3'_ . Y:-1 e H. 5 I V , 92 . - '1 _ I ._ ,_z;~ - __ PI ''_. -- '1_1~.' .-'_-.?-. '1': gww 5"» N" T°1f1=. - _ _ October12,"i'9h9 =1 .;,> Director, FBI ', _ _ e A * J r .-=,_;~.~- +.-.1L. - - ,;_;- :~¢ , --| ' nnwmur.Cuunn sscuanr muC5cHourIc:, --c --with P. _-_-.~; teliuel =5"?9* 1;.-_;+j _"%»:'_-~.--1 M ' j. +1-.,? Your file 100-16676-; ...;.,_'.jA __ A_ L B111¢ 10°-7239'! " 1"" ~ . -= »- - . I ~ ' =.. ,= -. e- I. .'~- - --" 5- " -.- -*. 1- -K .-4'; t=.v _ ~.." "-- - e e, :. 1-. ~- - _ .a~.:_- ~= *" Q-' --= Q-' d'A_:92>>. :~ 1'1--» ll; ;_._.*-'."§"=":-=:-i4;-.1":=*,==-";"-==~-L. -- » =;* ~ - = . 92V: . ,- < _ ~_,,__I . - . -.,,' . - -= ¢'--. --3-5; ~ .__--_1 I -_; -- . * i_ '»=-E-T37:-1~ -1n An e:|:e.n:Lnationof I92I1>j0¢§-'8-fill! reects thatthe lest .i¢.-W| port submittedby youroftice is datedFeb:-uu7 L,19149,; Ly}, * "1 ' '- - 1 ~-»' =;1 -;- ..c'1 T. ate as soon as poaaiblu - - - , . , . t Please eubnit another report "HQ. -3% _, 1»-. -

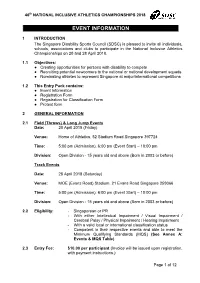

Event Information

46th NATIONAL INCLUSIVE ATHLETICS CHAMPIONSHIPS 2018 EVENT INFORMATION 1 INTRODUCTION The Singapore Disability Sports Council (SDSC) is pleased to invite all individuals, schools, associations and clubs to participate in the National Inclusive Athletics Championships on 20 and 28 April 2018. 1.1 Objectives: ● Creating opportunities for persons with disability to compete ● Recruiting potential newcomers to the national or national development squads ● Nominating athletes to represent Singapore at major/international competitions 1.2 This Entry Pack contains: ● Event Information ● Registration Form ● Registration for Classification Form ● Protest form 2 GENERAL INFORMATION 2.1 Field (Throws) & Long Jump Events Date: 20 April 2018 (Friday) Venue: Home of Athletics. 52 Stadium Road Singapore 397724 Time: 5:00 pm (Admission). 6:00 pm (Event Start) – 10:00 pm Division: Open Division - 15 years old and above (Born in 2003 or before) Track Events Date: 28 April 2018 (Saturday) Venue: MOE (Evans Road) Stadium. 21 Evans Road Singapore 259366 Time: 5:00 pm (Admission). 6:00 pm (Event Start) – 10:00 pm Division: Open Division - 15 years old and above (Born in 2003 or before) 2.2 Eligibility: - Singaporean or PR - With either Intellectual Impairment / Visual Impairment / Cerebral Palsy / Physical Impairment / Hearing Impairment - With a valid local or international classification status - Competent in their respective events and able to meet the Minimum Qualifying Standards (MQS) (See Annex A: Events & MQS Table) 2.3 Entry Fee: $10.00 per participant (Invoice will be issued upon registration, with payment instructions.) Page 1 of 12 46th NATIONAL INCLUSIVE ATHLETICS CHAMPIONSHIPS 2018 2.4 Registration 23rd March 2018 Deadline: Email completed forms to [email protected]. -

Athletics Classification Rules and Regulations 2

IPC ATHLETICS International Paralympic Committee Athletics Classifi cation Rules and Regulations January 2016 O cial IPC Athletics Partner www.paralympic.org/athleticswww.ipc-athletics.org @IPCAthletics ParalympicSport.TV /IPCAthletics Recognition Page IPC Athletics.indd 1 11/12/2013 10:12:43 Purpose and Organisation of these Rules ................................................................................. 4 Purpose ............................................................................................................................... 4 Organisation ........................................................................................................................ 4 1 Article One - Scope and Application .................................................................................. 6 International Classification ................................................................................................... 6 Interpretation, Commencement and Amendment ................................................................. 6 2 Article Two – Classification Personnel .............................................................................. 8 Classification Personnel ....................................................................................................... 8 Classifier Competencies, Qualifications and Responsibilities ................................................ 9 3 Article Three - Classification Panels ................................................................................ 11 4 Article Four -

July 23, 6997 Washington, DC 20002 (202) 54GGGGG

InThe Mattes Of= Senate Committee an GouemmentalAflairs Special Investigation - 1996 FEC Funds Hearfag Volume Number 8 July 23, 6997 Miller Reporting Cornpan. Inc. 507 C Street, NE. Washington,DC 20002 (202) 54GGGGG FAX: (202) 5461502 Original FiIe 0723sga8.a~~251 Pages Min-Uscrlpt@Fib? ID: I564470159 Word Index included dththis Min-U-Sdm Pmml i 114 'F~dLnleica;ona.,w k-IWO ha lor rmm arc Puc '[fkhu't uhich we I haVC Nch~suspidon.hrI review IhC 1111 in~~nfliclbyrhcrcqWlhatwemr*cforimmuniimmunityuldIhe !1111 rcquesc~.the~usticc0 armrmthasnotobj~~rCdt0gnnU 1'3 response of the Justice ocprrtmcnt in opporin# lhew h '1'4 of Unmunity lor nine 02Cr pplcwho arc lnvohcd UI the 1131 requcsu. '119Hsi IaiTeemplc case and who this Codnee.therefore. can 1141 The contlict is a xrious one. pyarululy in chc [mi call upon to me. 1151 lnermth of the North adPoindexter M, kCluK I [!I9 Ycr. the four arc socomewhar lugher up in the cham 21 ita ccrUinly conclude pnsoonrlly. u I bclimmst observers pq the tcmpk, and probably that IS wi~ythey arc or more IIV do. that in the aftermath of Le North and poindcncr ,['?I interest to ~eJusticc0epucment.becaux they had a more 1w decisions. once a congnuionalcommitm muimmunity to pa1 ccndrole. therefore may be more culpable or mybe of ['ai an Individual. it effectively forecloses the posshhty of llq mreauulance. rn a rucccurul prosecution of chat kbidud re@KklQ hc In Ihe second mmcr. which few Mr.Trie. about matters about which he or she will wsufy. whch MK drhe individuals wc arc seeking immunity. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 1 Heading Headingcontents

ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2017 NEW ZEALAND RIO 2016 PARALYMPIC GAMES TEAM OPENING CEREMONY PHOTO CREDIT: GETTY IMAGES PARALYMPICS NEW ZEALAND ANNUAL REPORT 2017 1 heading headingcontents 2 Officers and Officials 4 Chairman’s Report 6 Chief Executive’s Report 7 Governance Report 8 Commercial and Marketing Report 10 High Performance Report 11 High Performance Athlete Development Report 12 Community Development Report 14 Classification Report 16 Rio 2016 Paralympic Games 20 Future Paralympic Games 21 International Para Sport Results 22 Cyril Smith Legacy Fund Recipients 24 List of Paralympians 31 Financial Report 32 Directory and Statement of Compliance & Responsibility 33 Statement of Comprehensive Revenue & Expenses 34 Statement of Changes and Net Assets 35 Statement of Financial Position 36 Cash Flow Statement 37 Notes to the Accounts 45 Independent Auditor‘s Report 2 PARALYMPICS NEW ZEALAND ANNUAL REPORT 2017 officers & officials PNZ PATRON His Excellency LT GEN The Right Honourable Sir Jerry Mateparae (until August 2016) Her Excellency The Right Honourable Dame Patsy Reddy (from November 2016) PNZ BOARD Dr. Selwyn Maister QSM Ms. Catriona McBean Ms. Jana Rangooni (Chair) Mr. Mark Copeland Mr. Clive Power Ms. Jane Cotter (from February 2017) (until October 2016) Mr. Kagan Hindshaw (until Ms. Paula Tesoriero (MNZM) Mr. Duane Kale, ONZM October 2016, deceased) (from December 2016) PNZ ORDER Mr. J L McKie Mr. P Humphreys Mr. W F L Utley, OBE (deceased) OF MERIT MEMBERS Mr. J L H Savage, MBE Mr. D Kale, ONZM Mr. H J Pow (deceased) Mrs. K Condon Mr. T James Mr. P Holmes, CNZM (deceased) Mr. C Power Mr. -

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veteran Monthly Assistance Allowance for Disabled Veterans Training in Paralympic and Olympic Sports Program (VMAA) In partnership with the United States Olympic Committee and other Olympic and Paralympic entities within the United States, VA supports eligible service and non-service-connected military Veterans in their efforts to represent Team USA at the Paralympic Games, Olympic Games and other international sport competitions. The VA Office of National Veterans Sports Programs & Special Events provides a monthly assistance allowance for disabled Veterans training in Paralympic sports, as well as certain disabled Veterans selected for or competing with the national Olympic Team, as authorized by 38 U.S.C. 322(d) and Section 703 of the Veterans’ Benefits Improvement Act of 2008. Through the program, VA will pay a monthly allowance to a Veteran with either a service-connected or non-service-connected disability if the Veteran meets the minimum military standards or higher (i.e. Emerging Athlete or National Team) in his or her respective Paralympic sport at a recognized competition. In addition to making the VMAA standard, an athlete must also be nationally or internationally classified by his or her respective Paralympic sport federation as eligible for Paralympic competition. VA will also pay a monthly allowance to a Veteran with a service-connected disability rated 30 percent or greater by VA who is selected for a national Olympic Team for any month in which the Veteran is competing in any event sanctioned by the National Governing Bodies of the Olympic Sport in the United State, in accordance with P.L. -

Warm Springs Road and Green Valley Parkway Clark County, Nevada

Request for Letter of Map Revision Green Valley Area Warm Springs Road and Green Valley Parkway Clark County, Nevada Prepared for: CLARK COUNTY REGIONAL FLOOD CONTROL DISTRICT 500 S. Grand Central Parkway Las Vegas, NV 89155 Prepared by: PBS&J 2270 Corporate Circle, Suite 100 Henderson, Nevada 89074 (702) 263-7275 April 2, 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Description Paqe 1.o Introduction.. .................................................... 1 2.0 Area Descriptions.. .............................................. 1 2.1 Area A Description.. ............................................ ..l 2.2 Area B Description............................................... 2 2.3 Area C Description............................................... 2 2.4 Area D Description............................................... 2 3.0 Hydrologic & Hydraulic Modeling......................... .3 3.1 Area A Analysis .................................................... 3 3.2 Area B Analysis .................................................... 3 3.3 Area C Analysis .................................................... 5 3.4 Area D Analysis ....................................................6 4.0 Conclusion......................................................... 7 5.0 References......................................................... 7 Request for LOMR - Green Valley Area 4/02/04 Warm Springs Road and Green Valley Pkwy -I- APPENDICES A. FEMA Forms (Area’s A - D) Separate Set for Each of Four Area’s FEMA ‘Overview and Concurrence Form’ - MT-2 Form 1 FEMA ‘Riverine Hydrology -

Classification Report

World Para Athletics Classification Master List Summer Season 2017 Classification Report created by IPC Sport Data Management System Sport: Athletics | Season: Summer Season 2017 | Region: Oceania Region | NPC: Australia | Found Athletes: 114 Australia SDMS ID Family Name Given Name Gender Birth T Status F Status P Status Reason MASH 14982 Anderson Rae W 1997 T37 R F37 R-2024 10627 Arkley Natheniel M 1994 T54 C 33205 Ault-Connell Eliza W 1981 T54 C 1756 Ballard Angela W 1982 T53 C 26871 Barty Chris M 1988 T35 R F34 R MRR 1778 Beattie Carlee W 1982 T47 C F46 C 26763 Bertalli James M 1998 T37 R F37 R 17624 Blake Torita W 1995 T38 R-2022 32691 Bounty Daniel M 2001 T38 R-2022 13801 Burrows Thomas M 1990 T20 [TaR] R 29097 Byrt Eliesha W 1988 T20 [TaR] C 32689 Carr Blake M 1994 T20 [HozJ] C F20 N 10538 Carter Samuel M 1991 T54 C 1882 Cartwright Kelly W 1989 T63 C F63 C 29947 Charlton Julie W 1999 T54 C F57 C 1899 Chatman Aaron M 1987 T47 C 29944 Christiansen Mitchell M 1997 T37 R-2025 26224 Cleaver Erin W 2000 T38 R-2022 19971 Clifford Jaryd M 1999 T12 R-2023 F12 R-2023 29945 Colley Tamsin W 2002 T36 R-2023 F36 R-2020 1941 Colman Richard M 1984 T53 C 26990 Coop Brianna W 1998 T35 R-2022 19721 Copas Stacey W 1978 T51 R F52 C 32680 Crees Dayna W 2002 F34 R-2022 29973 Crombie Cameron M 1986 F38 R-2022 19964 Cronje Jessica W 1998 T37 R F37 R IPC Sport Data Management System Page 1 of 4 6 October 2021 at 07:08:42 CEST World Para Athletics Classification Master List Summer Season 2017 19546 Davidson Brayden M 1997 T36 R-2022 1978 Dawes Christie W -

WCHA Play Resumes with Trio of League Series Jan. 8-9 WCHA Public Relations Office Buckeyes Head to Minnesota, North Dakota Hosts Wisconsin in Fargo; Bemidji Sara R

WCHA ADMINISTraTIVE OFFICE Bruce M. McLeod Commissioner Carol LaBelle-Ehrhardt Assistant Commissioner of Operations Greg Shepherd Supervisor of Officials Mailing Address Western Collegiate Hockey Association 2211 S. Josephine Street, Room 302, ™ Denver, CO 80210 p: 303 871-4223. f: 303 871-4770. [email protected] January 5, 2010/For Immediate Release WCHA WOMEN’S OFFICE WCHA PLAY RESUMES WITH TrIO OF LEAGUE SERIES JAN. 8-9 WCHA PUblIC RElaTIONS OFFICE BUCKEYES HEAD TO MINNESOTA, NORTH DaKOTA HOSTS WISCONSIN IN FarGO; BEMIDJI Sara R. Martin STATE HOSTS MINNESOTA STATE; FOUR TEAMS – MINNESOTA, WISCONSIN, MINNESOTA Associate Commissioner p: 608 829-0104. f: 608 829-0105. DULUTH AND OHIO STATE – RANKED IN NaTION’S TOp 10; DEFENDING NaTIONal ChaMPION [email protected] WISCONSIN HOSTS U.S. WOMEN’S OlYMPIC TEAM JAN. 5; TICKETS ON SalE FOR 2010 WCHA Doug Spencer Associate Commissioner FINal FacE-OFF, March 6-7 AT RIDDER ARENA IN MINNEapOLIS for Public Relations p: 608 829-0100. f: 608 829-0200. MADISON, Wis. – With the holiday break over and four of the eight conference teams ranked in the nation’s [email protected] top 10, league competition in the Western Collegiate Hockey Association will resume this weekend with three Bill Brophy league series. Women’s Public Relations Director Play begins Friday and Saturday, Jan. 8-9, when league-leading and No. 2-ranked Minnesota entertains No. p: 608-277-0282. 10-ranked Ohio State, North Dakota hosts No. 6-ranked Wisconsin at the Urban Plains Center in Fargo, N.D., [email protected] and Bemidji State travels to Minnesota State, Mankato. -

Finish Top 20 Schools Scores 1 Arkansas Tech 296 306 602 +26 2

Sonoma State Women's Fall Invitational Foxtail Golf Club Rohnert Park, CA Par 72-5982 Yards Dates: Oct 17 - Oct 18 finish top 20 schools scores 1 Arkansas Tech 296 306 602 +26 2 Art, Academy of 301 306 607 +31 3 CSU - Chico State 297 318 615 +39 4 Sonoma State 316 301 617 +41 5 Holy Names 305 326 631 +55 6 CSU - East Bay 318 319 637 +61 7 Western Washington 327 311 638 +62 8 Point Loma 319 327 646 +70 9 Dominican (CA) 331 331 662 +86 finish top 20 players school scores 1 Avery Struck Arkansas Tech 70 75 145 +1 2 Vicky Kuo Art, Academy of 73 74 147 +3 3 Courtney Newport Holy Names 75 73 148 +4 4 Bianca Armanini CSU - Chico State 72 77 149 +5 5 Shu-Lin Lin Art, Academy of 77 74 151 +7 6 Sterling Hawkins Art, Academy of 74 78 152 +8 T7 Anna Frandsen Arkansas Tech 75 78 153 +9 T7 Caroline Fredensborg Arkansas Tech 76 77 153 +9 T7 Stephanie Sewell Western Washington 80 73 153 +9 T7 Haley Whitbeck Sonoma State 81 72 153 +9 T11 Erin Martens Sonoma State 80 74 154 +10 T11 Abbey McGrew CSU - Chico State 74 80 154 +10 T11 Sabrina Virtusio Sonoma State 76 78 154 +10 T14 Roxanne Matta * Art, Academy of 82 74 156 +12 T14 Samantha Oliva Sonoma State 79 77 156 +12 T16 Madison Beckett Dominican (CA) 78 79 157 +13 T16 Michelle Picca Point Loma 78 79 157 +13 T16 Jessica Sachs Arkansas Tech 75 82 157 +13 T19 Jamie Lopez Holy Names 74 84 158 +14 T19 Emily Rotter CSU - Chico State 78 80 158 +14 T19 Madison Stephens CSU - Chico State 73 85 158 +14 T19 Taylor Wyss CSU - East Bay 80 78 158 +14 GOLFSTAT COLLEGIATE SCORING SYSTEM Mark Laesch - COPYRIGHT © 2016,