Downloaded From: Usage Rights: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- Tive Works 4.0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M E T H O D O L O G Y & a R C H a E O M E T R Y 0 5

24 METHODOLOGY & ARCHAEOMETRY 05 • INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC CONFERENCE • PROCEEDINGS PROCEEDINGS • INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC CONFERENCE • METHODOLOGY & ARCHAEOMETRY 05 25 The Late Prehistory in Albania: a Review of Theory, Strategies of Research, and Valorization of Archaeological Heritage Esmeralda Agolli DOI:10.17234/9789531757799.3 Department of Archaeology and Culture Heritage Faculty of History and Philology University of Tirana Rruga e Elbasanit AL–1001 Tirana, Albania [email protected] In almost eight decades of explorations, the research in the field of prehistory in Albania demonstrated considerable dynamics, a series of seminal efforts to delve into the distant past, effects of external factors to instrumentalize the archaeological interpretations, various research strategies, and, of course, numerous efforts to valorize and preserve the data as a crucial testimony of culture heritage. Many different strategies of data collection, including systematic excavations, regional surveys, test pits and so on, has been extensively applied in a large number of field projects. However, while considering cohesively research agendas, scientific queries that yet remain to be addressed, as well as the potential for further explorations and the value that archaeological sites have gained beyond their discovery, some crucial matters need to be discussed. In this paper, I deal with the character of the archaeological research of prehis- tory in Albania and to what extent it impacts the understanding of the past, including both, flaws -

Crystal Reports

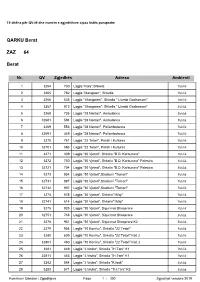

Të dhëna për QV-të dhe numrin e zgjedhësve sipas listës paraprake QARKU Berat ZAZ 64 Berat Nr. QV Zgjedhës Adresa Ambienti 1 3264 730 Lagjia "Kala",Shkolla Publik 2 3265 782 Lagjia "Mangalen", Shkolla Publik 3 3266 535 Lagjia " Mangalem", Shkolla " Llambi Goxhomani" Publik 4 3267 813 Lagjia " Mangalem", Shkolla " Llambi Goxhomani" Publik 5 3268 735 Lagjia "28 Nentori", Ambulanca Publik 6 32681 594 Lagjia "28 Nentori", Ambulanca Publik 7 3269 553 Lagjia "28 Nentori", Poliambulanca Publik 8 32691 449 Lagjia "28 Nentori", Poliambulanca Publik 9 3270 751 Lagjia "22 Tetori", Pallati I Kultures Publik 10 32701 593 Lagjia "22 Tetori", Pallati I Kultures Publik 11 3271 409 Lagjia "30 Vjetori", Shkolla "B.D. Karbunara" Publik 12 3272 750 Lagjia "30 Vjetori", Shkolla "B.D. Karbunara" Palestra Publik 13 32721 704 Lagjia "30 Vjetori", Shkolla "B.D. Karbunara" Palestra Publik 14 3273 854 Lagjia "30 Vjetori",Stadiumi "Tomori" Publik 15 32731 887 Lagjia "30 Vjetori",Stadiumi "Tomori" Publik 16 32732 907 Lagjia "30 Vjetori",Stadiumi "Tomori" Publik 17 3274 578 Lagjia "30 Vjetori", Shkolla"1Maji" Publik 18 32741 614 Lagjia "30 Vjetori", Shkolla"1Maji" Publik 19 3275 925 Lagjia "30 Vjetori", Sigurimet Shoqerore Publik 20 32751 748 Lagjia "30 Vjetori", Sigurimet Shoqerore Publik 21 3276 951 Lagjia "30 Vjetori", Sigurimet Shoqerore K2 Publik 22 3279 954 Lagjia "10 Korriku", Shkolla "22 Tetori" Publik 23 3280 509 Lagjia "10 Korriku", Shkolla "22 Tetori" Kati 2 Publik 24 32801 450 Lagjia "10 Korriku", Shkolla "22 Tetori" Kati 2 Publik 25 3281 649 Lagjia "J.Vruho", -

KFOS LOCAL and INTERNATIONAL VOLUME II.Pdf

EDITED BY IOANNIS ARMAKOLAS AGON DEMJAHA LOCAL AND AROLDA ELBASANI STEPHANIE SCHWANDNER- SIEVERS INTERNATIONAL DETERMINANTS OF KOSOVO’S STATEHOOD VOLUME II LOCAL AND INTERNATIONAL DETERMINANTS OF KOSOVO’S STATEHOOD —VOLUME II EDITED BY: IOANNIS ARMAKOLAS AGON DEMJAHA AROLDA ELBASANI STEPHANIE SCHWANDNER-SIEVERS Copyright ©2021 Kosovo Foundation for Open Society. All rights reserved. PUBLISHER: Kosovo Foundation for Open Society Imzot Nikë Prelaj, Vila 13, 10000, Prishtina, Kosovo. Issued in print and electronic formats. “Local and International Determinants of Kosovo’s Statehood: Volume II” EDITORS: Ioannis Armakolas Agon Demjaha Arolda Elbasani Stephanie Schwandner-Sievers PROGRAM COORDINATOR: Lura Limani Designed by Envinion, printed by Envinion, on recycled paper in Prishtina, Kosovo. ISBN 978-9951-503-06-8 CONTENTS ABOUT THE EDITORS 7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 12 INTRODUCTION 13 CULTURE, HERITAGE AND REPRESENTATIONS 31 — Luke Bacigalupo Kosovo and Serbia’s National Museums: A New Approach to History? 33 — Donjetë Murati and Stephanie Schwandner- Sievers An Exercise in Legitimacy: Kosovo’s Participation at 1 the Venice Biennale 71 — Juan Manuel Montoro Imaginaries and Media Consumptions of Otherness in Kosovo: Memories of the Spanish Civil War, Latin American Telenovelas and Spanish Football 109 — Julianne Funk Lived Religious Perspectives from Kosovo’s Orthodox Monasteries: A Needs Approach for Inclusive Dialogue 145 LOCAL INTERPRETATIONS OF INTERNATIONAL RULES 183 — Meris Musanovic The Specialist Chambers in Kosovo: A Hybrid Court between -

Academia De Ştiinţe a Moldovei Institutul Patrimoniului Cultural

E-ISSN 2537–6152 Categoria B ACADEMIA DE ŞTIINŢE A MOLDOVEI INSTITUTUL PATRIMONIULUI CULTURAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF MOLDOVA THE INSTITUTE OF CULTURAL HERITAGE АКАДЕМИЯ НАУК МОЛДОВЫ ИНСТИТУТ КУЛЬТУРНОГО НАСЛЕДИЯ REVISTA DE ETNOLOGIE ŞI CULTUROLOGIE Volumul XX THE JOURNAL OF ETHNOLOGY AND CULTUROLOGY Volume XX ЖУРНАЛ ЭТНОЛОГИИ И КУЛЬТУРОЛОГИИ Том XX CHIŞINĂU, 2016 Colegiul de redacție: Procop S. Redactor principal. Doctor în filologie, Duşacova N. Doctor în istorie, cercetător ştiinţific conferenţiar, director al Centrului de Etnologie al Insti- superior, Centrul de Tipologie şi Semiotică a Folclorului, tutului Patrimoniului Cultural al AȘM. svetlanaprocop@ Universitatea de Stat din Rusia (Moscova). dushakova@ mail.ru list.ru Zaicovschi T. Redactor responsabil. Doctor în filolo- Ghinoiu I. Doctor în geografie, cercetător ştiinţific gie, conferenţiar, cercetător ştiinţific coordonator la Cen- principal, gradul I, secretar ştiinţific al Institutului de trul de Etnologie al Institutului Patrimoniului Cultural. Etnografie şi Folclor „C. Brăiloiu”, Academia Română [email protected] (Bucureşti). [email protected] Damian V. Secretar responsabil. Doctor în istorie, Guboglo M. Doctor habilitat în istorie, profesor, cercetător ştiinţific superior la Centrul de Etnologie al vice-director al Institutului de Etnologie şi Antropolo- IPC al AȘM. [email protected] gie „N. Mikluho-Maklai”, Academia de Știinţe din Rusia Cara N. Doctor în filologie, cercetător ştiinţific co- (Moscova). [email protected] ordonator la Centrul de Etnologie al Institutului Patrimo- Nicoglo D. Doctor în istorie, cercetător ştiinţific niului Cultural al AȘM. [email protected] superior la Centrul de Etnologie al IPC al AȘM. Derlicki J. Doctor în etnologie, cercetător ştiinţific [email protected] la Departamentul de Etnologie al Institutului de Arhe- S te p a n o v V. -

![The History of Rome, Vol. 4 [10 AD]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9825/the-history-of-rome-vol-4-10-ad-199825.webp)

The History of Rome, Vol. 4 [10 AD]

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Vol. 4 [10 AD] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected]. -

Of Time, Honor, and Memory: Oral Law in Albania

Oral Tradition, 23/1 (2008): 3-14 Of Time, Honor, and Memory: Oral Law in Albania Fatos Tarifa This essay provides a historical account of the role of oral tradition in passing on from generation to generation an ancient code of customary law that has shaped and dominated the lives of northern Albanians until well into the mid-twentieth century. This traditional body of customary law is known as the Kode of Lekë Dukagjini. It represents a series of norms, mores, and injunctions that were passed down by word of mouth for generations and reputedly originally formulated by Lekë Dukagjini, an Albanian prince and companion-in-arms to Albania’s national hero, George Kastriot Skanderbeg (1405-68). Lekë Dukagjini ruled the territories of Pulati, Puka, Mirdita, Lura, and Luma in northern Albania—known today as the region of Dukagjini—until the Ottoman armies seized Albania’s northernmost city of Shkodër in 1479. Throughout the past five to six centuries this corpus of customary law has been referred to as Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit, Kanuni i Malsisë (the Code of the Highlands), or Kanuni i maleve (the Code of the Mountains). The “Code” is an inexact term, since Kanun, deriving from the Greek kanon, simultaneously signifies “norm,” “rule,” and “measure.” The Kanun, but most particularly the norm of vengeance, or blood taking, as its standard punitive apparatus, continue to this day to be a subject of historical, sociological, anthropological, and juridical interest involving various theoretical frames of reference from the dominant trends of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to today. The Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini was not the only customary law in Albania. -

Albanian Families' History and Heritage Making at the Crossroads of New

Voicing the stories of the excluded: Albanian families’ history and heritage making at the crossroads of new and old homes Eleni Vomvyla UCL Institute of Archaeology Thesis submitted for the award of Doctor in Philosophy in Cultural Heritage 2013 Declaration of originality I, Eleni Vomvyla confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature 2 To the five Albanian families for opening their homes and sharing their stories with me. 3 Abstract My research explores the dialectical relationship between identity and the conceptualisation/creation of history and heritage in migration by studying a socially excluded group in Greece, that of Albanian families. Even though the Albanian community has more than twenty years of presence in the country, its stories, often invested with otherness, remain hidden in the Greek ‘mono-cultural’ landscape. In opposition to these stigmatising discourses, my study draws on movements democratising the past and calling for engagements from below by endorsing the socially constructed nature of identity and the denationalisation of memory. A nine-month fieldwork with five Albanian families took place in their domestic and neighbourhood settings in the areas of Athens and Piraeus. Based on critical ethnography, data collection was derived from participant observation, conversational interviews and participatory techniques. From an individual and family group point of view the notion of habitus led to diverse conceptions of ethnic identity, taking transnational dimensions in families’ literal and metaphorical back- and-forth movements between Greece and Albania. -

Report of the First Season 'Dimal in Illyria' 2010

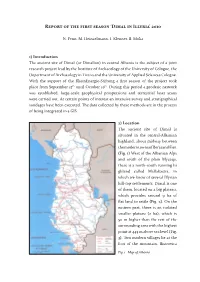

Report of the first season ‘Dimal in Illyria’ 2010 N. Fenn, M. Heinzelmann, I. Klenner, B. Muka 1) Introduction The ancient site of Dimal (or Dimallon) in central Albania is the subject of a joint research project lead by the Institute of Archaeology of the University of Cologne, the Department of Archaeology in Tirana and the University of Applied Sciences Cologne. With the support of the RheinEnergie-Stiftung a first season of the project took place from September 15th until October 19th. During this period a geodetic network was established, large-scale geophysical prospections and terrestrial laser scans were carried out. At certain points of interest an intensive survey and stratigraphical sondages have been executed. The data collected by these methods are in the process of being integrated in a GIS. 2) Location The ancient site of Dimal is situated in the central-Albanian highland, about midway between the modern towns of Berat and Fier. (Fig. 1) West of the Albanian Alps and south of the plain Myzeqe, there is a north-south running hi ghland called Mallakastra, in which we know of several Illyrian hill-top settlements. Dimal is one of them, located on a big plateau, which provides around 9 ha of flat land to settle (Fig. 2). On the eastern part, there is an isolated smaller plateau (2 ha), which is 50 m higher than the rest of the surrounding area with the highest point at 445 m above sea level (Fig. 3). Two modern villages lie at the foot of the mountain, Bistrovica Fig. 1 - Map of Albania REPORT OF THE FIRST SEASON ‘DIMAL IN ILLYRIA’ 2010 Fig. -

Greece • Crete • Turkey May 28 - June 22, 2021

GREECE • CRETE • TURKEY MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 Tour Hosts: Dr. Scott Moore Dr. Jason Whitlark organized by GREECE - CRETE - TURKEY / May 28 - June 22, 2021 May 31 Mon ATHENS - CORINTH CANAL - CORINTH – ACROCORINTH - NAFPLION At 8:30a.m. depart from Athens and drive along the coastal highway of Saronic Gulf. Arrive at the Corinth Canal for a brief stop and then continue on to the Acropolis of Corinth. Acro-corinth is the citadel of Corinth. It is situated to the southwest of the ancient city and rises to an elevation of 1883 ft. [574 m.]. Today it is surrounded by walls that are about 1.85 mi. [3 km.] long. The foundations of the fortifications are ancient—going back to the Hellenistic Period. The current walls were built and rebuilt by the Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Ottoman Turks. Climb up and visit the fortress. Then proceed to the Ancient city of Corinth. It was to this megalopolis where the apostle Paul came and worked, established a thriving church, subsequently sending two of his epistles now part of the New Testament. Here, we see all of the sites associated with his ministry: the Agora, the Temple of Apollo, the Roman Odeon, the Bema and Gallio’s Seat. The small local archaeological museum here is an absolute must! In Romans 16:23 Paul mentions his friend Erastus and • • we will see an inscription to him at the site. In the afternoon we will drive to GREECE CRETE TURKEY Nafplion for check-in at hotel followed by dinner and overnight. (B,D) MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 June 1 Tue EPIDAURAUS - MYCENAE - NAFPLION Morning visit to Mycenae where we see the remains of the prehistoric citadel Parthenon, fortified with the Cyclopean Walls, the Lionesses’ Gate, the remains of the Athens Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon in which we will actually enter. -

EUROPE a Albania • National Historical Museum – Tirana, Albania

EUROPE A Albania • National Historical Museum – Tirana, Albania o The country's largest museum. It was opened on 28 October 1981 and is 27,000 square meters in size, while 18,000 square meters are available for expositions. The National Historical Museum includes the following pavilions: Pavilion of Antiquity, Pavilion of the Middle Ages, Pavilion of Renaissance, Pavilion of Independence, Pavilion of Iconography, Pavilion of the National Liberation Antifascist War, Pavilion of Communist Terror, and Pavilion of Mother Teresa. • Et'hem Bey Mosque – Tirana, Albania o The Et’hem Bey Mosque is located in the center of the Albanian capital Tirana. Construction was started in 1789 by Molla Bey and it was finished in 1823 by his son Ethem Pasha (Haxhi Ethem Bey), great- grandson of Sulejman Pasha. • Mount Dajt – Tirana, Albania o Its highest peak is at 1,613 m. In winter, the mountain is often covered with snow, and it is a popular retreat to the local population of Tirana that rarely sees snow falls. Its slopes have forests of pines, oak and beech. Dajti Mountain was declared a National Park in 1966, and has since 2006 an expanded area of about 29,384 ha. It is under the jurisdiction and administration of Tirana Forest Service Department. • Skanderbeg Square – Tirana, Albania o Skanderbeg Square is the main plaza of Tirana, Albania named in 1968 after the Albanian national hero Skanderbeg. A Skanderbeg Monument can be found in the plaza. • Skanderbeg Monument – Skanderberg Square, Tirana, Albania o The monument in memory of Skanderbeg was erected in Skanderbeg Square, Tirana. -

PATOSI Traditë - Kulturë Qershor 2019

PATOSI Traditë - Kulturë qershor 2019 Traditë dhe Kulturë 1 Përmbajtja -PATOSI Monumentet e Kultit Informacion i përgjithshëm Manastiri i Shën Trifonit dhe Kultura të ndryshme, një qytet Kishat e Sheqishtes Greva e Naftëtarëve -RUZHDIE të Patosit 7 - 11 Mars 1927 Informacion i përgjithshëm Nafta Zharrëz Rezervuari i Ruzhdies Nafta Ruzhdie Monumentet e Kultit Ulliri Mekami i Drenies Flora dhe Fauna Varri i Baba Mustafait (të gjatit) Monumentet e Kulturës Monumentet e Natyrës Kalaja e Margëlliçit Ujvarat në kanionin e Siqecës Margëlliçi, dëshmitar i terrakotës së Rrapi i Zhugrit Afërditës -TRADITA MYZEQARE Tuma e Patosit Dasma Myzeqare Ura e Ofiçinës Bujqësia dhe Blegtoria Monumentet e Kultit Oda Myzeqare Kisha e “Shën Mëhillit” dhe Kishat e -TRADITA MALLAKASTRIOTE tjera të Sheqishtes Bujqësia dhe Blegtoria Monumentet e Natyrës Oda Mallakastriote Rrepet e Peshkëpijave -VESHJET KARAKTERISTIKE Punimet artizanale POPULLORE Disa nga objektet e hershme Veshjet Myzeqare kulturore Veshjet Mallakastriote -ZHARRËZA Veshjet Vllehe Informacion i përgjithshëm Veshjet Çame Vllehët në Myzeqe FESTIVALI “STREET ART” Rezervuari i Zharrzës Monumentet e Kulturës Novosela 2 Traditë dhe Kulturë “Patosi, Traditë - Kulturë”, është një botim i cili vjen në kuadër të Trashëgimisë Kulturore. Revista prezanton qytetin në aspektin e etnokulturor dhe historik, në funksion të komunitetit vendas dhe gjithë atyre që dëshirojnë ta vizitojnë atë nga afër. Patosi është zhvilluar si një qëndër e re banimi dhe shërbimi social për naftëtarët dhe familjet e tyre, të cilët e populluan qytetin dhe krijuan shtresime të larmishme social- kulturore të pasura me traditën dhe psikologjinë e zonave nga vinin. Lindja e qyteteve që vihet re në shekujt IV - III krijoi kushtet për zhvillimin e një prodhimtarie zejtare shumëdegëshe, e cila çoi në zgjerimin e veprimtarisë së tyre tregëtare si dhe rritjen e gjithanshme të ekonomisë monetare1. -

Mediterranean Divine Vintage Turkey & Greece

BULGARIA Sinanköy Manya Mt. NORTH EDİRNE KIRKLARELİ Selimiye Fatih Iron Foundry Mosque UNESCO B L A C K S E A MACEDONIA Yeni Saray Kırklareli Höyük İSTANBUL Herakleia Skotoussa (Byzantium) Krenides Linos (Constantinople) Sirra Philippi Beikos Palatianon Berge Karaevlialtı Menekşe Çatağı Prusias Tauriana Filippoi THRACE Bathonea Küçükyalı Ad hypium Morylos Neapolis Dikaia Heraion teikhos Achaeology Edessa park KOCAELİ Tragilos Antisara Perinthos Basilica UNESCO Abdera Maroneia TEKİRDAĞ (İZMİT) DÜZCE Europos Kavala Doriskos Nicomedia Pella Amphipolis Stryme Işıklar Mt. ALBANIA JOINAllante Lete Bormiskos Thessalonica Argilos THE SEA OF MARMARA SAKARYA MACEDONIANaoussa Apollonia Thassos Ainos (ADAPAZARI) UNESCO Thermes Aegae YALOVA Ceramic Furnaces Selectum Chalastra Strepsa Berea Iznik Lake Nicea Methone Cyzicus Vergina Petralona Samothrace Parion Roman theater Acanthos Zeytinli Ada Apamela Aisa Ouranopolis Hisardere Elimia PydnaMEDITERRANEAN Barçın Höyük BTHYNIA Dasaki Galepsos Yenibademli Höyük BURSA UNESCO Antigonia Thyssus Apollonia (Prusa) ÇANAKKALE Manyas Zeytinlik Höyük Arisbe Lake Ulubat Phylace Dion Akrothooi Lake Sane Parthenopolis GÖKCEADA Aktopraklık O.Gazi Külliyesi BİLECİK Asprokampos Kremaste Daskyleion UNESCO Höyük Pythion Neopolis Astyra Sundiken Mts. Herakleum Paşalar Sarhöyük Mount Athos Achmilleion Troy Pessinus Potamia Mt.Olympos Torone Hephaistia Dorylaeum BOZCAADA Sigeion Kenchreai Omphatium Gonnus Skione Limnos MYSIA Uludag ESKİŞEHİR Eritium DIVINE VINTAGE Derecik Basilica Sidari Oxynia Myrina Kaz Mt. Passaron Soufli Troas Kebrene Skepsis UNESCO Meliboea Cassiope Gure bath BALIKESİR Dikilitaş Kanlıtaş Höyük Aiginion Neandra Karacahisar Castle Meteora Antandros Adramyttium Corfu UNESCO Larissa Lamponeia Dodoni Theopetra Gülpinar Pioniai Kulluoba Hamaxitos Seyitömer Höyük Keçi çayırı Syvota KÜTAHYA Grava Polimedion Assos Gerdekkaya Assos Mt.Pelion A E GTURKEY E A N S E A &Pyrrha GREECEMadra Mt. (Cotiaeum) Kumbet Lefkimi Theudoria Pherae Mithymna Midas City Ellina EPIRUS Passandra Perperene Lolkos/Gorytsa Antissa Bahses Mt.