Have the Harmful Effects of Introduced Rats on Islands Been Exaggerated?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluating the Effectiveness of Salvage and Translocation of Striped Legless Lizards

Evaluating the effectiveness of salvage and translocation of Striped Legless Lizards Megan O’Shea February 2013 Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 243 Evaluating the effectiveness of salvage and translocation of Striped Legless Lizards Megan O’Shea February 2013 Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Department of Sustainability and Environment Heidelberg, Victoria Report produced by: Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Department of Sustainability and Environment PO Box 137 Heidelberg, Victoria 3084 Phone (03) 9450 8600 Website: www.dse.vic.gov.au/ari © State of Victoria, Department of Sustainability and Environment 2013 This publication is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 , no part may be reproduced, copied, transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical or graphic) without the prior written permission of the State of Victoria, Department of Sustainability and Environment. All requests and enquiries should be directed to the Customer Service Centre, 136 186 or email [email protected] Citation: O’Shea, M. (2013). Evaluating the effectiveness of salvage and translocation of Striped Legless Lizards. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 243. Department of Sustainability and Environment, Heidelberg. ISSN 1835-3827 (print) ISSN 1835-3835 (online) ISBN 978-1-74287-763-1 (print) ISBN 978-1-74287-764-8 (online) Disclaimer: This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. -

Quaternary Murid Rodents of Timor Part I: New Material of Coryphomys Buehleri Schaub, 1937, and Description of a Second Species of the Genus

QUATERNARY MURID RODENTS OF TIMOR PART I: NEW MATERIAL OF CORYPHOMYS BUEHLERI SCHAUB, 1937, AND DESCRIPTION OF A SECOND SPECIES OF THE GENUS K. P. APLIN Australian National Wildlife Collection, CSIRO Division of Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra and Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Mammalogy) American Museum of Natural History ([email protected]) K. M. HELGEN Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution, Washington and Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Mammalogy) American Museum of Natural History ([email protected]) BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY Number 341, 80 pp., 21 figures, 4 tables Issued July 21, 2010 Copyright E American Museum of Natural History 2010 ISSN 0003-0090 CONTENTS Abstract.......................................................... 3 Introduction . ...................................................... 3 The environmental context ........................................... 5 Materialsandmethods.............................................. 7 Systematics....................................................... 11 Coryphomys Schaub, 1937 ........................................... 11 Coryphomys buehleri Schaub, 1937 . ................................... 12 Extended description of Coryphomys buehleri............................ 12 Coryphomys musseri, sp.nov.......................................... 25 Description.................................................... 26 Coryphomys, sp.indet.............................................. 34 Discussion . .................................................... -

Atoll Research Bulletin No. 182 the Murine Rodents

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 182 THE MURINE RODENTS RATTUS RATTUS, EXULANS, AND NORVEGICUS AS AVIAN PREDATORS by F. I. Norman Issued by THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Washington, D.C., U.S.A. January 15,1975 Contents Page Introduction 1 References to Predation by Rats 3 Apterygiformes 3 Procellariiformes 3 Pelicaniformes 4 Ciconiiformes 4 Ans eriformes Gallif ormes Charadriiformes Columbiformes Psittaciformes Passeriformes lliscussion References THE MURINE RODENTS RATTUS RATTUS, EXULANS, AND NORVEGICUS AS AVIAN PREDATORS by F. I. Norman-1 / INTRODUCTION Few mammals have adventitiously accompanied man around the world more than members of the Murinae and of these, the most ubiquitous must surely be the --Rattus group. Three species, R. rattus Linn., R. norvegicus Berkenhout, and R. exulans T~eale),have been h~storically associated with-man, and their present distribution reflects such associations. Thus although -R. exulans is generally distributed through the Pacific region, -R. rattus and norvegicus are almost worldwide in distribution, having originated presumably in Asia Minor, as did exulans (walker 1964.). All have invaded, with man's assistance, habitats which previously did not include them, and they have developed varying degrees of commensalism with man. Neither --rattus nor norvegicus has entered antarctic ecosystems, but Law and Burstall (1956) recorded their presence on subantarctic Macquarie Island. Kenyon (1961) and Schiller (1956), however, have shown that norvegicus has become established in the arctic where localised populations are dependent on refuse as a food source during the winter. More frequently, reports bave been made of the over-running of islands by these alien rats. Tristan da Cunha is one such example (Elliott 1957; Holdgate 1960), and Dampier found rattus to be common on Ascension Island in 1701 though presently -norvegicus is more widespread there (nuffey 1964). -

Plant Charts for Native to the West Booklet

26 Pohutukawa • Oi exposed coastal ecosystem KEY ♥ Nurse plant ■ Main component ✤ rare ✖ toxic to toddlers coastal sites For restoration, in this habitat: ••• plant liberally •• plant generally • plant sparingly Recommended planting sites Back Boggy Escarp- Sharp Steep Valley Broad Gentle Alluvial Dunes Area ment Ridge Slope Bottom Ridge Slope Flat/Tce Medium trees Beilschmiedia tarairi taraire ✤ ■ •• Corynocarpus laevigatus karaka ✖■ •••• Kunzea ericoides kanuka ♥■ •• ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• Metrosideros excelsa pohutukawa ♥■ ••••• • •• •• Small trees, large shrubs Coprosma lucida shining karamu ♥ ■ •• ••• ••• •• •• Coprosma macrocarpa coastal karamu ♥ ■ •• •• •• •••• Coprosma robusta karamu ♥ ■ •••••• Cordyline australis ti kouka, cabbage tree ♥ ■ • •• •• • •• •••• Dodonaea viscosa akeake ■ •••• Entelea arborescens whau ♥ ■ ••••• Geniostoma rupestre hangehange ♥■ •• • •• •• •• •• •• Leptospermum scoparium manuka ♥■ •• •• • ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• Leucopogon fasciculatus mingimingi • •• ••• ••• • •• •• • Macropiper excelsum kawakawa ♥■ •••• •••• ••• Melicope ternata wharangi ■ •••••• Melicytus ramiflorus mahoe • ••• •• • •• ••• Myoporum laetum ngaio ✖ ■ •••••• Olearia furfuracea akepiro • ••• ••• •• •• Pittosporum crassifolium karo ■ •• •••• ••• Pittosporum ellipticum •• •• Pseudopanax lessonii houpara ■ ecosystem one •••••• Rhopalostylis sapida nikau ■ • •• • •• Sophora fulvida west coast kowhai ✖■ •• •• Shrubs and flax-like plants Coprosma crassifolia stiff-stemmed coprosma ♥■ •• ••••• Coprosma repens taupata ♥ ■ •• •••• •• -

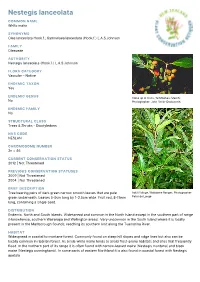

Nestegis Lanceolata

Nestegis lanceolata COMMON NAME White maire SYNONYMS Olea lanceolata Hook.f.; Gymnelaea lanceolata (Hook.f.) L.A.S.Johnson FAMILY Oleaceae AUTHORITY Nestegis lanceolata (Hook.f.) L.A.S.Johnson FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Native ENDEMIC TAXON Yes ENDEMIC GENUS Close up of fruits, Te Moehau (March). No Photographer: John Smith-Dodsworth ENDEMIC FAMILY No STRUCTURAL CLASS Trees & Shrubs - Dicotyledons NVS CODE NESLAN CHROMOSOME NUMBER 2n = 46 CURRENT CONSERVATION STATUS 2012 | Not Threatened PREVIOUS CONSERVATION STATUSES 2009 | Not Threatened 2004 | Not Threatened BRIEF DESCRIPTION Tree bearing pairs of dark green narrow smooth leaves that are pale Adult foliage, Waitakere Ranges. Photographer: green underneath. Leaves 5-9cm long by 1-2.5cm wide. Fruit red, 8-11mm Peter de Lange long, containing a single seed. DISTRIBUTION Endemic. North and South Islands. Widespread and common in the North Island except in the southern part of range (Horowhenua, southern Wairarapa and Wellington areas). Very uncommon in the South Island where it is locally present in the Marlborough Sounds, reaching its southern limit along the Tuamarina River. HABITAT Widespread in coastal to montane forest. Commonly found on steep hill slopes and ridge lines but also can be locally common in riparian forest. As a rule white maire tends to avoid frost-prone habitats and sites that frequently flood. In the northern part of its range it is often found with narrow-leaved maire (Nestegis montana) and black maire (Nestegis cunninghamii). In some parts of eastern Northland it is also found in coastal forest with Nestegis apetala. FEATURES Stout gynodioecious spreading tree up to 20 m tall usually forming a domed canopy; trunk up to c. -

Vascular Flora of Motuora Island, Hauraki Gulf Shelley Heiss-Dunlop & Jo Fillery

Vascular flora of Motuora Island, Hauraki Gulf Shelley Heiss-Dunlop & Jo Fillery Introduction 1988). A total of 141 species (including 14 ferns) were Motuora Island lies in the Hauraki Gulf southwest of recorded. Exotic plants confined to the gardens Kawau Island, approximately 3km from Mahurangi around the buildings at Home Bay were not included Heads, and 5km from Wenderholm Regional Park, in Dowding’s (1988) list. Dowding (1988) commented Waiwera. This 80ha island is long and narrow on four adventive species that were “well-established” (approximately 2km x c. 600m at its widest) with a and that “may present problems” (presumably for a relatively flat top, reaching 75m asl. The land rises future restoration project). These species were abruptly, in places precipitously, from the shoreline so boneseed (Chrysanthemoides monilifera), boxthorn that the area of the undulating ‘level’ top is (Lycium ferocissimum), gorse (Ulex europaeus) and comparatively extensive. Composed of sedimentary kikuyu grass (Pennisetum clandestinum). All four strata from the Pakiri formation of the Waitemata species still require ongoing control. However, as a Group (Lower Miocene age, approximately 20 million years old), Motuora is geologically similar to other result of ongoing weed eradication endeavours, inner Hauraki gulf islands such as Tiritiri Matangi, boxthorn has been reduced to a few isolated sites, Kawau, Waiheke and Motuihe Islands (Ballance 1977; and boneseed once widespread on the island is Edbrooke 2001). considerably reduced also, occurring in high densities now only on the northern end of the island (Lindsay History 2006). Gorse and kikuyu are controlled where these Motuora Island was farmed, from as early as 1853 species inhibit revegetation plantings. -

Structural Diversity and Contrasted Evolution of Cytoplasmic Genomes in Flowering Plants :A Phylogenomic Approach in Oleaceae Celine Van De Paer

Structural diversity and contrasted evolution of cytoplasmic genomes in flowering plants :a phylogenomic approach in Oleaceae Celine van de Paer To cite this version: Celine van de Paer. Structural diversity and contrasted evolution of cytoplasmic genomes in flowering plants : a phylogenomic approach in Oleaceae. Vegetal Biology. Université Paul Sabatier - Toulouse III, 2017. English. NNT : 2017TOU30228. tel-02325872 HAL Id: tel-02325872 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02325872 Submitted on 22 Oct 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. REMERCIEMENTS Remerciements Mes premiers remerciements s'adressent à mon directeur de thèse GUILLAUME BESNARD. Tout d'abord, merci Guillaume de m'avoir proposé ce sujet de thèse sur la famille des Oleaceae. Merci pour ton enthousiasme et ta passion pour la recherche qui m'ont véritablement portée pendant ces trois années. C'était un vrai plaisir de travailler à tes côtés. Moi qui étais focalisée sur les systèmes de reproduction chez les plantes, tu m'as ouvert à un nouveau domaine de la recherche tout aussi intéressant qui est l'évolution moléculaire (même si je suis loin de maîtriser tous les concepts...). Tu as toujours été bienveillant et à l'écoute, je t'en remercie. -

Changing Invaders: Trends of Gigantism in Insular Introduced Rats

Environmental Conservation (2018) 45 (3): 203–211 C Foundation for Environmental Conservation 2018 doi:10.1017/S0376892918000085 Changing invaders: trends of gigantism in insular THEMATIC SECTION Humans and Island introduced rats Environments ALEXANDRA A.E. VAN DER GEER∗ Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands Date submitted: 7 November 2017; Date accepted: 20 January 2018; First published online 14 March 2018 SUMMARY within short historical periods (Rowe-Rowe & Crafford 1992; Michaux et al. 2007;Renaudet al. 2013; Lister & Hall 2014). The degree and direction of morphological change in Additionally, invasive species may also alter the evolutionary invasive species with a long history of introduction pathway of native species by mechanisms such as niche are insufficiently known for a larger scale than the displacement, hybridization, introgression and predation (e.g. archipelago or island group. Here, I analyse data for 105 Mooney & Cleland 2001; Stuart 2014; van der Geer et al. island populations of Polynesian rats, Rattus exulans, 2013). The timescale and direction of evolution of invasive covering the entirety of Oceania and Wallacea to test rodents are, however, insufficiently known. Data on how whether body size differs in insular populations and, they evolve in interaction with native species are urgently if so, what biotic and abiotic features are correlated needed with the increasing pace of introductions today due to with it. All insular populations of this rat, except globalized transport: invasive rodent species are estimated to one, exhibit body sizes up to twice the size of their have already colonized more than 80% of the world’s island mainland conspecifics. -

Northland CMS Volume I

CMS CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT STRATEGY N orthland 2014–2024, Volume I Operative 29 September 2014 CONSERVATION106B MANAGEMENT STRATEGY NORTHLAND107B 2014–2024, Volume I Operative108B 29 September 2014 Cover109B image: Waikahoa Bay campsite, Mimiwhangata Scenic Reserve. Photo: DOC September10B 2014, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISBN10B 978-0-478-15017-9 (print) ISBN102B 978-0-478-15019-3 (online) This103B document is protected by copyright owned by the Department of Conservation on behalf of the Crown. Unless indicated otherwise for specific items or collections of content, this copyright material is licensed for re- use under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 New Zealand licence. In essence, you are free to copy, distribute and adapt the material, as long as you attribute it to the Department of Conservation and abide by the other licence terms. To104B view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/nz/U U This105B publication is produced using paper sourced from well-managed, renewable and legally logged forests. Contents802B 152B Foreword803 7 Introduction804B 8 Purpose809B of conservation management strategies 8 CMS810B structure 9 CMS81B term 10 Relationship812B with other Department of Conservation strategic documents and tools 10 Relationship813B with other planning processes 11 Legislative814B tools 11 Exemption89B from land use consents 11 Closure890B of areas and access restrictions 11 Bylaws891B and regulations 12 Conservation892B management plans 12 International815B obligations 12 Part805B -

Vascular Plants of an Unclassified Islet, Cape Brett Peninsula, Northern New Zealand, by E.K. Cameron, P

TANE 28,1982 VASCULAR PLANTS OF AN UNCLASSIFIED ISLET, CAPE BRETT PENINSULA, NORTHERN NEW ZEALAND by E.K. Cameron Department of Botany, University of Auckland, Private Bag, Auckland SUMMARY Seventy indigenous and 2 adventive vascular plants taxa are recorded for the "unmodified" islet. Its botanical value exceeds its small size because of the modification of the adjacent Cape Brett Peninsula and nearby islands. INTRODUCTION The islet is situated only a few metres off the northern coastline of Cape Brett Peninsula (Fig. 1). This steep beehive-shaped greywacke islet, less than two hectares in area, supports an excellent cover of indigenous vegetation compared with the adjacent goat (Copra hircus) browsed mainland. Approximately thirty minutes was spent on the islet during a four day botanical survey of Cape Brett Peninsula carried out for the Department of Lands and Survey, Auckland, in June 1980 (Cameron 1980). Time permitted only a single south-west to north-east traverse, returning to the starting point via the north-west littoral. PLANT COMMUNITIES For ease of description four plant associations (Fig. 2) are recognised although it must be remembered that these are by no means distinct as they grade into one another. Area 1: Coastal Rock. The amount of coastal rock on the islet is proportional to the degree of wave exposure and thus the north-eastern side of the islet has the greatest amount of exposed rock. Plants such as Asplenium flaccidum ssp. haurakiense, Samolus repens and the shore lobelia (Lobelia anceps) are frequently found growing in cracks and crevices. Others found here include the N.Z. -

PLANTING GUIDE - STREET TREES 27 CHARACTER AREA: Papamoa West

CHARACTER AREA: Papamoa East Description This.is.a.large.geographical.area.taking.in.the.coastal.strip.from.Sandhurst.Drive.to.the.end.of.Papamoa. Beach.Road..The.area.has.been.intensively.developed.in.recent.years..The.berm.size.is.generally.small.. The.older.residential.areas.have.overhead.services.present. The.most.common.street.tree.species.in.this.area.are.Karaka.(Corynocarpus laevigatus),.Olive.(Olea europaea).Pohutukawa.(Metrosideros excelsa).and.Washingtonia.palm.(Washingtonia robusta). The.tree.species.that.are.features.of.the.area.are.the.Pine.trees.(Pinus radiata).along.the.beach.front. and.at.Papamoa.Domain.and.the.Monterey.cypress.(Cupressus macrocarpa).and.Gum.trees.(Eucalyptus species).in.the.Palm.Beach.stormwater.reserve. Preferred species for significant roads Domain Road Metrosideros excelsa:.Pohutukawa Banksia integrifolia:.Banksia Gravatt Road Magnolia grandiflora:.Bull.bay Evans Road Metrosideros excelsa:.Pohutukawa Olea europaea:.Olive Parton Road Metrosideros excelsa:.Pohutukawa Palm Beach Boulevard 26 PAPAMOA EAST PAPAMOA Preferred species for minor roads Pacific View Road Metrosideros excelsa:.Pohutukawa Metrosideros excelsa:.Pohutukawa Olea europaea:.Olive Alberta magna:.Natal.flame.tree Magnolia grandiflora:.Bull.bay Magnolia ‘little gem’:.Southern.magnolia Planchonella costata:.Tawapou. Tristaniopsis laurina:.Water.gum Preferred species for use under power lines Alberta magna:.Natal.flame.tree Olea ‘el greco’:.Olive Magnolia ‘little gem’:.Southern.magnolia Hardy tree species are essential in the coastal strip. Pictured Magnolia grandiflora PLANTING GUIDE - STREET TREES 27 CHARACTER AREA: Papamoa West Description Preferred species for Preferred species for use under This.is.primarily.a.rural.area.that.is.likely.to.be.intensively.developed. significant roads power lines in.the.future;.a.portion.of.this.area.takes.in.the.Papamoa.east. -

Island Rule and Bone Metabolism in Fossil Murines from Timor

Island rule and bone metabolism in fossil murines from Timor Miszkiewicz, JJ, Louys, J, Beck, RMD, Mahoney, P, Aplin, K and O’Connor, S http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/biolinnean/blz197 Title Island rule and bone metabolism in fossil murines from Timor Authors Miszkiewicz, JJ, Louys, J, Beck, RMD, Mahoney, P, Aplin, K and O’Connor, S Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/56252/ Published Date 2020 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Page 1 of 47 Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 1 2 3 Island rule and bone metabolism in fossil murines from Timor 4 5 6 7 1* 2 3 4 ** 8 Justyna J. Miszkiewicz , Julien Louys , Robin M. D. Beck , Patrick Mahoney , Ken Aplin , 9 Sue O’Connor5,6 10 11 12 13 1School of Archaeology and Anthropology, College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian 14 National University, 0200 Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia 15 16 17 2Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution, Environmental Futures Research Institute, 18 Griffith University, 4111 Brisbane, Queensland, Australia 19 20 21 3School of Environment Forand Life PeerSciences,