GMS News Autumn 2019 Weeks 28-36

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Butterflies and Moths of Ada County, Idaho, United States

Heliothis ononis Flax Bollworm Moth Coptotriche aenea Blackberry Leafminer Argyresthia canadensis Apyrrothrix araxes Dull Firetip Phocides pigmalion Mangrove Skipper Phocides belus Belus Skipper Phocides palemon Guava Skipper Phocides urania Urania skipper Proteides mercurius Mercurial Skipper Epargyreus zestos Zestos Skipper Epargyreus clarus Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus spanna Hispaniolan Silverdrop Epargyreus exadeus Broken Silverdrop Polygonus leo Hammock Skipper Polygonus savigny Manuel's Skipper Chioides albofasciatus White-striped Longtail Chioides zilpa Zilpa Longtail Chioides ixion Hispaniolan Longtail Aguna asander Gold-spotted Aguna Aguna claxon Emerald Aguna Aguna metophis Tailed Aguna Typhedanus undulatus Mottled Longtail Typhedanus ampyx Gold-tufted Skipper Polythrix octomaculata Eight-spotted Longtail Polythrix mexicanus Mexican Longtail Polythrix asine Asine Longtail Polythrix caunus (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) Zestusa dorus Short-tailed Skipper Codatractus carlos Carlos' Mottled-Skipper Codatractus alcaeus White-crescent Longtail Codatractus yucatanus Yucatan Mottled-Skipper Codatractus arizonensis Arizona Skipper Codatractus valeriana Valeriana Skipper Urbanus proteus Long-tailed Skipper Urbanus viterboana Bluish Longtail Urbanus belli Double-striped Longtail Urbanus pronus Pronus Longtail Urbanus esmeraldus Esmeralda Longtail Urbanus evona Turquoise Longtail Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail Urbanus teleus Teleus Longtail Urbanus tanna Tanna Longtail Urbanus simplicius Plain Longtail Urbanus procne Brown Longtail -

New Moths from Texas (Noctuidae, Tortricidae)

1968 Joltrnal of the Lepidopterists' Societu 133 NEW MOTHS FROM TEXAS (NOCTUIDAE, TORTRICIDAE) ANDRE BLANCHARD 3023 Underwood, Houston, Texas As a retirement hobby, I decided, six years ago, to catalog the moths of Texas. My wife and I have been collecting moths all over Texas for the last four years. As the work progressed, I came to realize that I may have to settle, more modestly, for a "Contributions Toward A Catalog of the Moths of Texas." The number of species in my collection which had apparently never been taken in Texas is quite large, and the number of those which seem to be new to science, particularly from the mountain ranges and desert areas of West Texas, is much larger than I ever expected. I have been fortunate in interesting several specialists in describing some of these new species: Dr. C. L. Hogue (196S), Mr. McElvare ( 1966), Dr. E. L. Todd (1966) have described three. Difficult cases are now and, in the future, will be submitted to experts. I have de scribed the male of a fourth species (1966), the female of which was described by Dr. F. H. Hindge (1966). While getting more material for my intcnded catalog, I shall describe as many of the new species as I can name without becoming guilty of adding to the confusion which already exists in some genera. In the present paper, I describe six new noctuids and one tortricid species. All types were collected by A. &. M. E. Blanchard. Acronicta vallis cola Blanchard, new species (PI. I, fig. J; PI. -

Larval Protein Quality of Six Species of Lepidoptera (Saturniidaeo Sphingidae, Noctuidae)

Larval Protein Quality of Six Species of Lepidoptera (Saturniidaeo Sphingidae, Noctuidae) STEPHEN V. LANDRY,I GENE R. DEFOLIART,IANP MILTON L. SUNDE, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin 53706 J. Econ. Entomol. 79; 600-604 (I98€) ABSTRACT Six lepidopteran species representing three families were evaluated for their potential use as protein supplements for poultry. Proximate and amino acid analyses were conducted on larval powders of each species. Larvae ranged from 49.4 to 58.1% crude protein on a dry-weight basis. Amino acid analysis indicated deficiencies in arginine, me- thionine, cysteine, and possibly lysine, when larvae are used in chick rations. In a chick- feeding trial with three of the species, however, these deffciencies were not substantiated: the average weight gained by chicks fed the lepidopteran-supplemented dlet did not differ significantly from that of.chicks fed a conventional corn/soybean control diet. LnprpoptBne ARE among the many species of in- by feeding trials on poultry (Ichhponani and Ma- sects that have played an important role in nutri- Iek 1971, Wijayasinghe and Rajaguru 1977). tion, especially in areas where human and domes- To determine and compare the protein quality tic animal populations are subject to chronic protein of a wider assortment of lepidopterous larvae, we deficiency (e.g., Bodenheimer 1951, Quin 1959, conducted proximate and amino acid analyses on Ruddle 1973, Conconi and Bourges 1977, Malaise larvae of six species representing three families. and Parent 1980, Conconi et al. 1984). Conconi et These included the cecropia moth, Hgalophora ce- al. (f9Sa), for example, listed 12 species in 8 fam- cropia (L.), and the promethea moth, Callosamia ilies that are gathered and consumed in Mexico. -

Garden Moth Scheme Report 2016

Garden Moth Scheme Report 2016 Heather Young – April 2017 1 GMS Report 2016 CONTENTS PAGE Introduction 2 Top 30 species 2016 3 Population trends (?) of our commonest garden moths 5 Autumn Moths 12 Winter GMS 2016-17 14 Antler Moth infestations 16 GMS Annual Conference 2017 19 GMS Sponsors 20 Links & Acknowledgements 21 Cover photograph: Fan-foot (R. Young) Introduction The Garden Moth Scheme (GMS) welcomes participants from all parts of the United Kingdom and Ireland, and in 2016 received 341 completed recording forms, slightly fewer than last year (355). The scheme is divided into 12 regions, monitoring 233 species of moth in every part of the UK and Ireland (the ‘Core Species’), along with a variable number of ‘Regional Species’. For each of the last seven years, we have had records from over 300 sites across the UK and Ireland, and later in the report there are a series of charts representing the population trends (or fluctuations) of our most abundant species over this period. The database has records dating back to 2003 when the scheme began in the West Midlands, and now contains over 1 ¼ million records, providing a very valuable resource to researchers. Scientists and statisticians from Birmingham and Manchester Universities are amongst those interested in using our data, as well as the ongoing research being undertaken by the GMS’s own John Wilson. There is an interesting follow-up article by Evan Lynn on the Quarter 4 GMS newsletter piece by Duncan Brown on Antler Moth infestations, and a report on the very successful 2017 Annual Conference in Apperley Village Hall, near Tewkesbury. -

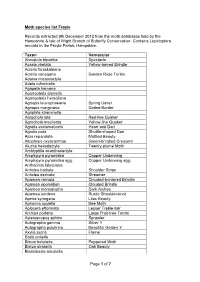

Page 1 of 7 Moth Species List Froyle Records

Moth species list Froyle Records extracted 9th December 2012 from the moth databases held by the Hampshire & Isle of Wight Branch of Butterfly Conservation. Contains Lepidoptera records in the Froyle Parish, Hampshire. Taxon Vernacular Abrostola tripartita Spectacle Acasis viretata Yellow-barred Brindle Acleris forsskaleana Acleris variegana Garden Rose Tortrix Adaina microdactyla Adela rufimitrella Agapeta hamana Agonopterix arenella Agonopterix heracliana Agriopis leucophaearia Spring Usher Agriopis marginaria Dotted Border Agriphila straminella Agrochola lota Red-line Quaker Agrochola macilenta Yellow-line Quaker Agrotis exclamationis Heart and Dart Agrotis puta Shuttle-shaped Dart Alcis repandata Mottled Beauty Allophyes oxyacanthae Green-brindled Crescent Alucita hexadactyla Twenty-plume Moth Amblyptilia acanthadactyla Amphipyra pyramidea Copper Underwing Amphipyra pyramidea agg. Copper Underwing agg. Anthophila fabriciana Anticlea badiata Shoulder Stripe Anticlea derivata Streamer Apamea crenata Clouded-bordered Brindle Apamea epomidion Clouded Brindle Apamea monoglypha Dark Arches Apamea sordens Rustic Shoulder-knot Apeira syringaria Lilac Beauty Aphomia sociella Bee Moth Aplocera efformata Lesser Treble-bar Archips podana Large Fruit-tree Tortrix Asteroscopus sphinx Sprawler Autographa gamma Silver Y Autographa pulchrina Beautiful Golden Y Axylia putris Flame Batia unitella Biston betularia Peppered Moth Biston strataria Oak Beauty Blastobasis adustella Page 1 of 7 Blastobasis lacticolella Cabera exanthemata Common Wave Cabera -

Check List of Noctuid Moths (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae And

Бiологiчний вiсник МДПУ імені Богдана Хмельницького 6 (2), стор. 87–97, 2016 Biological Bulletin of Bogdan Chmelnitskiy Melitopol State Pedagogical University, 6 (2), pp. 87–97, 2016 ARTICLE UDC 595.786 CHECK LIST OF NOCTUID MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA: NOCTUIDAE AND EREBIDAE EXCLUDING LYMANTRIINAE AND ARCTIINAE) FROM THE SAUR MOUNTAINS (EAST KAZAKHSTAN AND NORTH-EAST CHINA) A.V. Volynkin1, 2, S.V. Titov3, M. Černila4 1 Altai State University, South Siberian Botanical Garden, Lenina pr. 61, Barnaul, 656049, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Tomsk State University, Laboratory of Biodiversity and Ecology, Lenina pr. 36, 634050, Tomsk, Russia 3 The Research Centre for Environmental ‘Monitoring’, S. Toraighyrov Pavlodar State University, Lomova str. 64, KZ-140008, Pavlodar, Kazakhstan. E-mail: [email protected] 4 The Slovenian Museum of Natural History, Prešernova 20, SI-1001, Ljubljana, Slovenia. E-mail: [email protected] The paper contains data on the fauna of the Lepidoptera families Erebidae (excluding subfamilies Lymantriinae and Arctiinae) and Noctuidae of the Saur Mountains (East Kazakhstan). The check list includes 216 species. The map of collecting localities is presented. Key words: Lepidoptera, Noctuidae, Erebidae, Asia, Kazakhstan, Saur, fauna. INTRODUCTION The fauna of noctuoid moths (the families Erebidae and Noctuidae) of Kazakhstan is still poorly studied. Only the fauna of West Kazakhstan has been studied satisfactorily (Gorbunov 2011). On the faunas of other parts of the country, only fragmentary data are published (Lederer, 1853; 1855; Aibasov & Zhdanko 1982; Hacker & Peks 1990; Lehmann et al. 1998; Benedek & Bálint 2009; 2013; Korb 2013). In contrast to the West Kazakhstan, the fauna of noctuid moths of East Kazakhstan was studied inadequately. -

Garden Moth Scheme Report 2017

Garden Moth Scheme Report 2017 Heather Young – April 2018 1 GMS Report 2017 CONTENTS PAGE Introduction 2 Top 30 Species 2017 3 Scientific Publications 4 Abundant and Widespread Species 8 Common or Garden Moths 11 Winter GMS 2017-18 15 Coordination Changes 16 GMS Annual Conference 16 GMS Sponsors 17 Links & Acknowledgements 18 Cover photograph: Peppered Moth (H. Young) Introduction The Garden Moth Scheme (GMS) welcomes participants from all parts of the United Kingdom and Ireland, and in 2017 received 360 completed recording forms, an increase of over 5% on 2016 (341). We have consistently received records from over 300 sites across the UK and Ireland since 2010, and now have almost 1 ½ million records in the GMS database. Several scientific papers using the GMS data have now been published in peer- reviewed journals, and these are listed in this report, with the relevant abstracts, to illustrate how the GMS records are used for research. The GMS is divided into 12 regions, monitoring 233 species of moth in every part of the UK and Ireland (the ‘Core Species’), along with a variable number of ‘Regional Species’. A selection of core species whose name suggests they should be found commonly, or in our gardens, is highlighted in this report. There is a round-up of the 2017-18 Winter Garden Moth Scheme, which attracted a surprisingly high number of recorders (102) despite the poor weather, a summary of the changes taking place in the GMS coordination team for 2018, and a short report on the 2018 Annual Conference, but we begin as usual with the Top 30 for GMS 2017. -

Moths of Ohio Guide

MOTHS OF OHIO field guide DIVISION OF WILDLIFE This booklet is produced by the ODNR Division of Wildlife as a free publication. This booklet is not for resale. Any unauthorized INTRODUCTION reproduction is prohibited. All images within this booklet are copyrighted by the Division of Wildlife and it’s contributing artists and photographers. For additional information, please call 1-800-WILDLIFE. Text by: David J. Horn Ph.D Moths are one of the most diverse and plentiful HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE groups of insects in Ohio, and the world. An es- Scientific Name timated 160,000 species have thus far been cata- Common Name Group and Family Description: Featured Species logued worldwide, and about 13,000 species have Secondary images 1 Primary Image been found in North America north of Mexico. Secondary images 2 Occurrence We do not yet have a clear picture of the total Size: when at rest number of moth species in Ohio, as new species Visual Index Ohio Distribution are still added annually, but the number of species Current Page Description: Habitat & Host Plant is certainly over 3,000. Although not as popular Credit & Copyright as butterflies, moths are far more numerous than their better known kin. There is at least twenty Compared to many groups of animals, our knowledge of moth distribution is very times the number of species of moths in Ohio as incomplete. Many areas of the state have not been thoroughly surveyed and in some there are butterflies. counties hardly any species have been documented. Accordingly, the distribution maps in this booklet have three levels of shading: 1. -

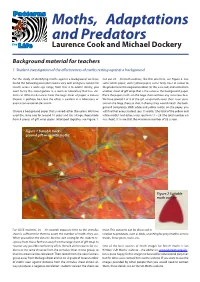

Moths, Adaptations and Predators

Patterns Moths, Adaptations and Predators forLife MOTHS Laurence Cook and Michael Dockery Background material for teachers 1. Student investigation of the effectiveness of moths resting against a background For the study of identifying moths against a background we have Cut out 20 – 30 moth outlines, like this one here, see Figure 2. Use found the following procedure works very well and gives consistent some white paper, some yellow paper, some fairly close in colour to results across a wide age range, from Year 2 to adults! Ideally, you the predominant background colour (in this case red) and some from want to try this investigation in a room or laboratory that has stu- another sheet of gift wrap that is the same as the background paper. dents at different distances from the large sheet of paper: a lecture Place the paper moths on the large sheet without any conscious bias. theatre is perhaps best but the effect is evident in a laboratory or We have placed 2 or 3 of the gift wrap moths over their `true` posi- even a conventional classroom. tion on the large sheet so that, in theory, they would match the back- ground completely. With white and yellow moths on the paper, you Choose a background paper that is varied rather than plain. We have will find that every student sees 11 moths (the total of the yellow and used the same one for around 10 years and it is a large sheet made white moths) and others may see from 11 – 26 (the total number on from 4 pieces of gift wrap paper sellotaped together, see Figure 1. -

Botolph's Bridge, Hythe Redoubt, Hythe Ranges West And

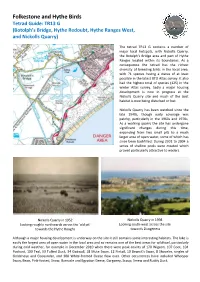

Folkestone and Hythe Birds Tetrad Guide: TR13 G (Botolph’s Bridge, Hythe Redoubt, Hythe Ranges West, and Nickolls Quarry) The tetrad TR13 G contains a number of major local hotspots, with Nickolls Quarry, the Botolph’s Bridge area and part of Hythe Ranges located within its boundaries. As a consequence the tetrad has the richest diversity of breeding birds in the local area, with 71 species having a status of at least possible in the latest BTO Atlas survey. It also had the highest total of species (125) in the winter Atlas survey. Sadly a major housing development is now in progress at the Nickolls Quarry site and much of the best habitat is now being disturbed or lost. Nickolls Quarry has been watched since the late 1940s, though early coverage was patchy, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s. As a working quarry the site has undergone significant changes during this time, expanding from two small pits to a much larger area of open water, some of which has since been backfilled. During 2001 to 2004 a series of shallow pools were created which proved particularly attractive to waders. Nickolls Quarry in 1952 Nickolls Quarry in 1998 Looking roughly northwards across the 'old pit' Looking south-west across the site towards the Hythe Roughs towards Dungeness Although a major housing development is underway on the site it still contains some interesting habitats. The lake is easily the largest area of open water in the local area and so remains one of the best areas for wildfowl, particularly during cold weather, for example in December 2010 when there were peak counts of 170 Wigeon, 107 Coot, 104 Pochard, 100 Teal, 53 Tufted Duck, 34 Gadwall, 18 Mute Swan, 12 Pintail, 10 Bewick’s Swan, 8 Shoveler, singles of Goldeneye and Goosander, and 300 White-fronted Geese flew over. -

Winter Cutworm: a New Pest Threat in Oregon J

OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION SERVICE Winter Cutworm: A New Pest Threat in Oregon J. Green, A. Dreves, B. McDonald, and E. Peachey Introduction Winter cutworm is the common name for the larval stage of the large yellow underwing moth (Noctua pronuba [Lepidoptera: Noctuidae]). The cutworm has tolerance for cold temperatures, and larval feeding activity persists throughout fall and winter. Adult N. pronuba moths have been detected in Oregon for at least a decade, and the species is common in many different ecological habitats. Epidemic outbreaks of adult moths have occurred periodically in this region, resulting in captures of up to 500 moths per night. However, larval feeding by N. pronuba has not been a problem in Oregon until recently. In 2013 and 2014, there were isolated instances reported, including damage by larvae to sod near Portland and defoliation of herb and flower gardens in Corvallis. In 2015, large numbers of larvae were observed around homes, within golf courses, and in field crops located in Oregon and Washington. Winter cutworms have a wide host range across agricultural, urban, and natural landscapes (Table Photo: Nate McGhee, © Oregon State University. 1, page 2) and are a concern as a potential crop pest that can cause considerable damage in a short highlights general information about winter amount of time. Above-ground damage occurs when cutworm, including identification, scouting recom- larvae chew through tissues near ground level, cut- mendations, and potential control measures. ting the stems off plants. Leaf chewing and root feeding also have been observed. Winter cutworms Jessica Green, faculty research assistant, Department of are gregarious, which means they feed and move in Horticulture; Amy J. -

Corn Earworm, Helicoverpa Zea (Boddie) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)1 John L

EENY-145 Corn Earworm, Helicoverpa zea (Boddie) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)1 John L. Capinera2 Distribution California; and perhaps seven in southern Florida and southern Texas. The life cycle can be completed in about 30 Corn earworm is found throughout North America except days. for northern Canada and Alaska. In the eastern United States, corn earworm does not normally overwinter suc- Egg cessfully in the northern states. It is known to survive as far north as about 40 degrees north latitude, or about Kansas, Eggs are deposited singly, usually on leaf hairs and corn Ohio, Virginia, and southern New Jersey, depending on the silk. The egg is pale green when first deposited, becoming severity of winter weather. However, it is highly dispersive, yellowish and then gray with time. The shape varies from and routinely spreads from southern states into northern slightly dome-shaped to a flattened sphere, and measures states and Canada. Thus, areas have overwintering, both about 0.5 to 0.6 mm in diameter and 0.5 mm in height. overwintering and immigrant, or immigrant populations, Fecundity ranges from 500 to 3000 eggs per female. The depending on location and weather. In the relatively mild eggs hatch in about three to four days. Pacific Northwest, corn earworm can overwinter at least as far north as southern Washington. Larva Upon hatching, larvae wander about the plant until they Life Cycle and Description encounter a suitable feeding site, normally the reproductive structure of the plant. Young larvae are not cannibalistic, so This species is active throughout the year in tropical and several larvae may feed together initially.