Moths, Adaptations and Predators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Butterflies and Moths of Ada County, Idaho, United States

Heliothis ononis Flax Bollworm Moth Coptotriche aenea Blackberry Leafminer Argyresthia canadensis Apyrrothrix araxes Dull Firetip Phocides pigmalion Mangrove Skipper Phocides belus Belus Skipper Phocides palemon Guava Skipper Phocides urania Urania skipper Proteides mercurius Mercurial Skipper Epargyreus zestos Zestos Skipper Epargyreus clarus Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus spanna Hispaniolan Silverdrop Epargyreus exadeus Broken Silverdrop Polygonus leo Hammock Skipper Polygonus savigny Manuel's Skipper Chioides albofasciatus White-striped Longtail Chioides zilpa Zilpa Longtail Chioides ixion Hispaniolan Longtail Aguna asander Gold-spotted Aguna Aguna claxon Emerald Aguna Aguna metophis Tailed Aguna Typhedanus undulatus Mottled Longtail Typhedanus ampyx Gold-tufted Skipper Polythrix octomaculata Eight-spotted Longtail Polythrix mexicanus Mexican Longtail Polythrix asine Asine Longtail Polythrix caunus (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) Zestusa dorus Short-tailed Skipper Codatractus carlos Carlos' Mottled-Skipper Codatractus alcaeus White-crescent Longtail Codatractus yucatanus Yucatan Mottled-Skipper Codatractus arizonensis Arizona Skipper Codatractus valeriana Valeriana Skipper Urbanus proteus Long-tailed Skipper Urbanus viterboana Bluish Longtail Urbanus belli Double-striped Longtail Urbanus pronus Pronus Longtail Urbanus esmeraldus Esmeralda Longtail Urbanus evona Turquoise Longtail Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail Urbanus teleus Teleus Longtail Urbanus tanna Tanna Longtail Urbanus simplicius Plain Longtail Urbanus procne Brown Longtail -

GMS News Autumn 2019 Weeks 28-36

GMS News Autumn 2019 Weeks 28-36 Contents Editorial Norman Lowe 1 Overview GMS 2019 4th Quarter Evan Lynn 2 My move to the “Dark Side” David Baker 12 Another snippet! (VC73) Rhian & Adam Davies 17 Emperors, admirals and chimney sweepers, a book review Peter Major 15 GMS collaboration with Cairngorms Connect Stephen Passey 22 How and when to release trapped moths? Norman Lowe 23 Garden Moth Scheme South Wales Conference Norman Lowe 23 Clifden Nonpareil Michael Sammes 24 Tailpiece Norman Lowe 24 Lepidopteran Crossword No. 12 Nonconformist 25 Communications & links 26 GMS sponsors 27 Editorial – Norman Lowe Welcome to the final Garden Moth Scheme Quarterly Report of 2019. We have a bumper Christmas edition for you this time with a good variety of articles from lots of different contributors. Of course these always represent our contributors’ personal views, with which you might agree or disagree. And if so, let’s hear from you! We start as always with Evan’s roundup of the quarter’s results comparing moth catches with weather conditions as they occurred throughout the period. This time he has chosen to compare Ireland and Scotland, the northern and western extremities of our study area. They are also our two largest “regions” (OK I know they (and Wales) don’t like to be called regions but I can’t think of a better alternative) and the ones with the largest numbers of vice counties with no GMS recorders. I’ll return to this theme in my Tailpiece. Evan has also focused on the Setaceous Hebrew Character, a species that seems to vary possibly more than any other from place to place. -

Catalogue2013 Web.Pdf

bwfp British Wild Flower Plants www.wildflowers.co.uk Plants for Trade Plants for Home Specialist Species Wildflower Seed Green Roof Plants Over 350 species Scan here to of British native buy online plants 25th Anniversary Year Finding Us British Wild Flower Plants Burlingham Gardens 31 Main Road North Burlingham Norfolk NR13 4TA Phone / Fax: (01603) 716615 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.wildflowers.co.uk Twitter: @WildflowersUK Nursery Opening Times Monday to Thursday: 10.00am - 4.00pm Friday: 10.00am - 2.30pm Please note that we are no longer open at weekends or Bank Holidays. Catalogue Contents Contact & Contents Page 02 About Us Page 03 Mixed Trays Pages 04-05 Reed Beds Page 06 Green Roofs Page 07 Wildflower Seeds Page 08 Planting Guide Pages 09-10 Attracting Wildlife Page 11 Rabbit-Proof Plants Page 12 List of Plants Pages 13-50 Scientific Name Look Up Pages 51-58 Terms & Conditions Page 59 www.wildflowers.co.uk 2 Tel/Fax:(01603)716615 About Us Welcome.... About Our Plants We are a family-run nursery, situated in Norfolk on a Our species are available most of the year in: six acre site. We currently stock over 350 species of 3 native plants and supply to all sectors of the industry Plugs: Young plants in 55cm cells with good rootstock. on a trade and retail basis. We are the largest grower of native plants in the UK and possibly Europe. Provenance Our species are drawn from either our own seed collections or from known provenance native sources. We comply with the Flora Locale Code of Practice. -

List of Animal Species with Ranks October 2017

Washington Natural Heritage Program List of Animal Species with Ranks October 2017 The following list of animals known from Washington is complete for resident and transient vertebrates and several groups of invertebrates, including odonates, branchipods, tiger beetles, butterflies, gastropods, freshwater bivalves and bumble bees. Some species from other groups are included, especially where there are conservation concerns. Among these are the Palouse giant earthworm, a few moths and some of our mayflies and grasshoppers. Currently 857 vertebrate and 1,100 invertebrate taxa are included. Conservation status, in the form of range-wide, national and state ranks are assigned to each taxon. Information on species range and distribution, number of individuals, population trends and threats is collected into a ranking form, analyzed, and used to assign ranks. Ranks are updated periodically, as new information is collected. We welcome new information for any species on our list. Common Name Scientific Name Class Global Rank State Rank State Status Federal Status Northwestern Salamander Ambystoma gracile Amphibia G5 S5 Long-toed Salamander Ambystoma macrodactylum Amphibia G5 S5 Tiger Salamander Ambystoma tigrinum Amphibia G5 S3 Ensatina Ensatina eschscholtzii Amphibia G5 S5 Dunn's Salamander Plethodon dunni Amphibia G4 S3 C Larch Mountain Salamander Plethodon larselli Amphibia G3 S3 S Van Dyke's Salamander Plethodon vandykei Amphibia G3 S3 C Western Red-backed Salamander Plethodon vehiculum Amphibia G5 S5 Rough-skinned Newt Taricha granulosa -

Species Assessment for Jair Underwing

Species Status Assessment Class: Lepidoptera Family: Noctuidae Scientific Name: Catocala jair Common Name: Jair underwing Species synopsis: Two subspecies of Catocala exist-- Catocala jair and Catocala jair ssp2. Both occur in New York. Subspecies 2 has seldom been correctly identified leading to false statements that the species is strictly Floridian. Nearly all literature on the species neglects the widespread "subspecies 2." Cromartie and Schweitzer (1997) had it correct. Sargent (1976) discussed and illustrated the taxon but was undecided as to whether it was C. jair. It has also been called C. amica form or variety nerissa and one Syntype of that arguably valid taxon is jair and another is lineella. The latter should be chosen as a Lectotype to preserve the long standing use of jair for this species. Both D.F. Schweitzer and L.F. Gall have determined that subspecies 2 and typical jair are conspecific. The unnamed taxon should be named but there is little chance it is a separate species (NatureServe 2012). I. Status a. Current and Legal Protected Status i. Federal ____ Not Listed____________________ Candidate? _____No______ ii. New York ____Not Listed; SGCN_____ ___________________________________ b. Natural Heritage Program Rank i. Global _____G4?___________________________________________________________ ii. New York ______SNR_________ ________ Tracked by NYNHP? ____Yes____ Other Rank: None 1 Status Discussion: The long standing G4 rank needs to be re-evaluated. New Jersey, Florida, and Texas would probably drive the global rank. The species is still locally common on Long Island, but total range in New York is only a very small portion of Suffolk County (NatureServe 2012). II. Abundance and Distribution Trends a. -

Garden Moth Scheme Report 2016

Garden Moth Scheme Report 2016 Heather Young – April 2017 1 GMS Report 2016 CONTENTS PAGE Introduction 2 Top 30 species 2016 3 Population trends (?) of our commonest garden moths 5 Autumn Moths 12 Winter GMS 2016-17 14 Antler Moth infestations 16 GMS Annual Conference 2017 19 GMS Sponsors 20 Links & Acknowledgements 21 Cover photograph: Fan-foot (R. Young) Introduction The Garden Moth Scheme (GMS) welcomes participants from all parts of the United Kingdom and Ireland, and in 2016 received 341 completed recording forms, slightly fewer than last year (355). The scheme is divided into 12 regions, monitoring 233 species of moth in every part of the UK and Ireland (the ‘Core Species’), along with a variable number of ‘Regional Species’. For each of the last seven years, we have had records from over 300 sites across the UK and Ireland, and later in the report there are a series of charts representing the population trends (or fluctuations) of our most abundant species over this period. The database has records dating back to 2003 when the scheme began in the West Midlands, and now contains over 1 ¼ million records, providing a very valuable resource to researchers. Scientists and statisticians from Birmingham and Manchester Universities are amongst those interested in using our data, as well as the ongoing research being undertaken by the GMS’s own John Wilson. There is an interesting follow-up article by Evan Lynn on the Quarter 4 GMS newsletter piece by Duncan Brown on Antler Moth infestations, and a report on the very successful 2017 Annual Conference in Apperley Village Hall, near Tewkesbury. -

Immature Stages of the Marbled Underwing, Catocala Marmorata (Noctuidae)

JOURNAL OF THE LEPIDOPTERISTS' SOCIETY Volume 54 2000 Number 4 Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 54(4), 2000,107- 110 IMMATURE STAGES OF THE MARBLED UNDERWING, CATOCALA MARMORATA (NOCTUIDAE) JOHN W PEACOCK 185 Benzler Lust Road, Marion, Ohio 43302, USA AND LAWRE:-JCE F GALL Entomology Division, Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520, USA ABSTRACT. The immature stages of C. marmorata are described and illustrated for the first time, along with biological and foodplant notes. Additional key words: underwing moths, Indiana, life history, Populus heterophylla. The Marbled Underwing, Catocala marrrwrata Ed REARING NOTES wards 1864, is generally an uncommon species whose present center of distribution is the central and south Ova were secured from a worn female C. rnarmorata central United States east of the Mississippi River collected at a baited tree at 2300 CST on 11 September (Fig. 1d). Historically, the range of C. marmorata ex 1994, in Point Twp. , Posey Co., Indiana. The habitat is tended somewhat farther to the north, as far as south mesic lowland flatwoods, with internal swamps of two ern New England (open circles in Fig. Id; see Holland types: (1) buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis L.) 1903, Barnes & McDunnough 1918, Sargent 1976), (Rubiaceae), cypress (Taxodium distichum L. but the species has not been recorded from these lo (Richaud)) (Taxodiaceae), and swamp cottonwood calities in the past 50 years, and the reasons for its ap (Populus heterophylla L.); and (2) overcup oak (Quer parent range contraction remain unknown. cus lyrata Walt.) (Fagaceae) and swamp cottonwood. We are not aware of any previously published infor The female was confined in a large grocery bag (17.8 X mation on the early stages or larval foodplant(s) for C. -

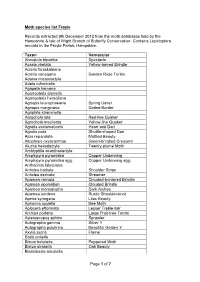

Page 1 of 7 Moth Species List Froyle Records

Moth species list Froyle Records extracted 9th December 2012 from the moth databases held by the Hampshire & Isle of Wight Branch of Butterfly Conservation. Contains Lepidoptera records in the Froyle Parish, Hampshire. Taxon Vernacular Abrostola tripartita Spectacle Acasis viretata Yellow-barred Brindle Acleris forsskaleana Acleris variegana Garden Rose Tortrix Adaina microdactyla Adela rufimitrella Agapeta hamana Agonopterix arenella Agonopterix heracliana Agriopis leucophaearia Spring Usher Agriopis marginaria Dotted Border Agriphila straminella Agrochola lota Red-line Quaker Agrochola macilenta Yellow-line Quaker Agrotis exclamationis Heart and Dart Agrotis puta Shuttle-shaped Dart Alcis repandata Mottled Beauty Allophyes oxyacanthae Green-brindled Crescent Alucita hexadactyla Twenty-plume Moth Amblyptilia acanthadactyla Amphipyra pyramidea Copper Underwing Amphipyra pyramidea agg. Copper Underwing agg. Anthophila fabriciana Anticlea badiata Shoulder Stripe Anticlea derivata Streamer Apamea crenata Clouded-bordered Brindle Apamea epomidion Clouded Brindle Apamea monoglypha Dark Arches Apamea sordens Rustic Shoulder-knot Apeira syringaria Lilac Beauty Aphomia sociella Bee Moth Aplocera efformata Lesser Treble-bar Archips podana Large Fruit-tree Tortrix Asteroscopus sphinx Sprawler Autographa gamma Silver Y Autographa pulchrina Beautiful Golden Y Axylia putris Flame Batia unitella Biston betularia Peppered Moth Biston strataria Oak Beauty Blastobasis adustella Page 1 of 7 Blastobasis lacticolella Cabera exanthemata Common Wave Cabera -

Garden Moth Scheme Report 2017

Garden Moth Scheme Report 2017 Heather Young – April 2018 1 GMS Report 2017 CONTENTS PAGE Introduction 2 Top 30 Species 2017 3 Scientific Publications 4 Abundant and Widespread Species 8 Common or Garden Moths 11 Winter GMS 2017-18 15 Coordination Changes 16 GMS Annual Conference 16 GMS Sponsors 17 Links & Acknowledgements 18 Cover photograph: Peppered Moth (H. Young) Introduction The Garden Moth Scheme (GMS) welcomes participants from all parts of the United Kingdom and Ireland, and in 2017 received 360 completed recording forms, an increase of over 5% on 2016 (341). We have consistently received records from over 300 sites across the UK and Ireland since 2010, and now have almost 1 ½ million records in the GMS database. Several scientific papers using the GMS data have now been published in peer- reviewed journals, and these are listed in this report, with the relevant abstracts, to illustrate how the GMS records are used for research. The GMS is divided into 12 regions, monitoring 233 species of moth in every part of the UK and Ireland (the ‘Core Species’), along with a variable number of ‘Regional Species’. A selection of core species whose name suggests they should be found commonly, or in our gardens, is highlighted in this report. There is a round-up of the 2017-18 Winter Garden Moth Scheme, which attracted a surprisingly high number of recorders (102) despite the poor weather, a summary of the changes taking place in the GMS coordination team for 2018, and a short report on the 2018 Annual Conference, but we begin as usual with the Top 30 for GMS 2017. -

Harper's Island Wetlands Butterflies & Moths (2020)

Introduction Harper’s Island Wetlands (HIW) nature reserve, situated close to the village of Glounthaune on the north shore of Cork Harbour is well known for its birds, many of which come from all over northern Europe and beyond, but there is a lot more to the wildlife at the HWI nature reserve than birds. One of our goals it to find out as much as we can about all aspects of life, both plant and animal, that live or visit HIW. This is a report on the butterflies and moths of HIW. Butterflies After birds, butterflies are probably the one of the best known flying creatures. While there has been no structured study of them on at HIW, 17 of Ireland’s 33 resident and regular migrant species of Irish butterflies have been recorded. Just this summer we added the Comma butterfly to the island list. A species spreading across Ireland in recent years possibly in response to climate change. Hopefully we can set up regular monitoring of the butterflies at HIW in the next couple of years. Butterfly Species Recorded at Harper’s Island Wetlands up to September 2020. Colias croceus Clouded Yellow Pieris brassicae Large White Pieris rapae Small White Pieris napi Green-veined White Anthocharis cardamines Orange-tip Lycaena phlaeas Small Copper Polyommatus icarus Common Blue Celastrina argiolus Holly Blue Vanessa atalanta Red Admiral Vanessa cardui Painted Lady Aglais io Peacock Aglais urticae Small Tortoiseshell Polygonia c-album Comma Speyeria aglaja Dark-green Fritillary Pararge aegeria Speckled Wood Maniola jurtina Meadow Brown Aphantopus hyperantus Ringlet Moths One group of insects that are rarely seen by visitors to HIW is the moths. -

Moths of Ohio Guide

MOTHS OF OHIO field guide DIVISION OF WILDLIFE This booklet is produced by the ODNR Division of Wildlife as a free publication. This booklet is not for resale. Any unauthorized INTRODUCTION reproduction is prohibited. All images within this booklet are copyrighted by the Division of Wildlife and it’s contributing artists and photographers. For additional information, please call 1-800-WILDLIFE. Text by: David J. Horn Ph.D Moths are one of the most diverse and plentiful HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE groups of insects in Ohio, and the world. An es- Scientific Name timated 160,000 species have thus far been cata- Common Name Group and Family Description: Featured Species logued worldwide, and about 13,000 species have Secondary images 1 Primary Image been found in North America north of Mexico. Secondary images 2 Occurrence We do not yet have a clear picture of the total Size: when at rest number of moth species in Ohio, as new species Visual Index Ohio Distribution are still added annually, but the number of species Current Page Description: Habitat & Host Plant is certainly over 3,000. Although not as popular Credit & Copyright as butterflies, moths are far more numerous than their better known kin. There is at least twenty Compared to many groups of animals, our knowledge of moth distribution is very times the number of species of moths in Ohio as incomplete. Many areas of the state have not been thoroughly surveyed and in some there are butterflies. counties hardly any species have been documented. Accordingly, the distribution maps in this booklet have three levels of shading: 1. -

Type Material at the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, with Lectotype Designations*

SYSTEMATICS OF MOTHS IN THE GENUS CA TOCALA (LEPIDOPTERA: NOCTUIDAE). II. TYPE MATERIAL AT THE MUSEUM OF COMPARATIVE ZOOLOGY, HARVARD UNIVERSITY, WITH LECTOTYPE DESIGNATIONS* BY LAWRENCE F. GALL Entomology Division, Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511 USA INTRODUCTION The recognized Nearctic species in the noctuid moth genus Cato- cala Schrank (1802) presently number ca. 100, with a synonymy comprising over 350 names. The Nearctic Catocala will be revised in a forthcoming "Moths of America North of Mexico" Fascicle, the taxonomic groundwork for which is appearing first in articles dis- cussing the types in institutional collections (see Gall & Hawks, 1990). The present paper examines the taxonomic status of 18 Nearctic Catocala names, based on type material at the Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ), Harvard University. THE MCZ CATOCALA TYPES A total of 7 Catocala holotypes was located during searches of the pinned MCZ Lepidoptera collection. The applicabilities and taxo- nomic ranks of these 7 Catocala names are without any question, and summary diagnoses are given in Tables 1-2. Syntype(s) located at the MCZ for another 9 Catocala names require lectotype designa- tions and/or further discussion, as follows: Catocala adoptiva Grote, 1874, p. 96. In the text of the original description, Grote (1874b) states only that "a number of specimens [are] in the Museum of Comparative Zoology," but offers the notation in his formal diagnosis, sug- gesting a limitation of the syntype""series to two specimens. This pair of specimens and others clearly from the original type lot were easily located at the MCZ, and the head male labelled "Type" is chosen here as LECTOTYPE for adoptiva (see Figure 1).