Citizen Initiated Internet Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YPE Statutes, Last Update November 2020

1 YPE Statutes, Last update November 2020 Statutes of Young Pirates of Europe § 1 General Provisions (1) Name The name of the association is "Young Pirates of Europe a.s.b.l.", abbreviated "YPE". Both the full and the abbreviated names may be used indistinguishably. A list of official translations of the association's name which may be used by the member associations is included in the Annex. (2) Seat The seat of the association is at the following address: 1a rue de Luxembourg, 8184 Kopstal, Luxembourg. EPIC may move the seat anywhere in Luxembourg by simple majority vote. The board may do so as well unanimously. (3) Language English shall be the working language of the association. Any initiatives and proposals can only be adopted if they have been translated into English prior to the start of the decision-making process on the level of the association. In the event of divergence or of doubt between these statutes in the original version in English and any version in another language, the English language version prevails. 2 YPE Statutes, Last update November 2020 § 2 Goals The main goal of YPE is to bring together European pirate youth organisations and other youth organisations that work on digital issues and for transparency in government, participating democracy and civil rights as well as their members, improving not only the coordination of their political work, but also supporting cultural and personal exchange. As a federation of youth organisations, education and personal development of young people as well as the exchange of ideas and support of eachother is an equally important aim of YPE. -

Tor: the Second-Generation Onion Router (2014 DRAFT V1)

Tor: The Second-Generation Onion Router (2014 DRAFT v1) Roger Dingledine Nick Mathewson Steven Murdoch The Free Haven Project The Free Haven Project Computer Laboratory [email protected] [email protected] University of Cambridge [email protected] Paul Syverson Naval Research Lab [email protected] Abstract Perfect forward secrecy: In the original Onion Routing We present Tor, a circuit-based low-latency anonymous com- design, a single hostile node could record traffic and later munication service. This Onion Routing system addresses compromise successive nodes in the circuit and force them limitations in the earlier design by adding perfect forward se- to decrypt it. Rather than using a single multiply encrypted crecy, congestion control, directory servers, integrity check- data structure (an onion) to lay each circuit, Tor now uses an ing, configurable exit policies, anticensorship features, guard incremental or telescoping path-building design, where the nodes, application- and user-selectable stream isolation, and a initiator negotiates session keys with each successive hop in practical design for location-hidden services via rendezvous the circuit. Once these keys are deleted, subsequently com- points. Tor is deployed on the real-world Internet, requires promised nodes cannot decrypt old traffic. As a side benefit, no special privileges or kernel modifications, requires little onion replay detection is no longer necessary, and the process synchronization or coordination between nodes, and provides of building circuits is more reliable, since the initiator knows a reasonable tradeoff between anonymity, usability, and ef- when a hop fails and can then try extending to a new node. -

Sustainable Banking. Implications for an Ethical Dimension of Finance of Social Enterprise Performance

STUDIA PRAWNO-EKONOMICZNE, t. CIV, 2017 PL ISSN 0081-6841; e-ISSN 2450-8179 s. 287–301 DOI: 10.26485/SPE/2017/104/16 Paweł MIKOŁAJCZAK* SUSTAINABLE BANKING. IMPLICATIONS FOR AN ETHICAL DIMENSION OF FINANCE OF SOCIAL ENTERPRISE PERFORMANCE (Summary) The article evaluates potential of sustainable banking as an important element of ethical finance system, supporting social enterprises financially. The article describes an alternative character of ethical banking against the risks resulting from the involvement of social external investors into investment ventures realized by social enterprises. Thus, it analyzes selected financial indexes of ethical banks against commercial banking institutions and it also assesses principles and criteria of finance by sustainable banking. Conclusions refer to non-credit forms of social enterprise finance. Keywords: sustainable banking; social entrepreneurship; credit; ethical finance JEL Classification: G01, G22, G23, L31 1. Introduction Modern commercial banks are strongly oriented to using a financial leverage to maximize profits, contributing to excessive financialization of economy and creating conditions for crisis1. Increase in importance and value of financial assets in comparison to tangible assets occurs. Also, importance of financial motives increases, most of all, of those referring to the profit and risk in a process of making economic decisions, and their influence on an effective performance of economic entities and social behaviors2. Financialization may contribute to conflicts between * Ph.D., The Department of Money and Banking at Poznań University of Economics; e-mail: [email protected] 1 M. Ratajczak, Ekonomia i edukacja ekonomiczna w dobie finansyzacji gospodarki, Ekonomista 2012/2, pp. 207–220. 2 K. Jajuga, W poszukiwaniu miar ryzyka finansowego, in: J. -

65. Jahrgang 1996

AMTLICHES NACHRICHTENORGAN DES DEUTSCHEN KANU-VERBANDES E.V. Redaktion: Dieter Reinmuth, Wuppertal 65. Jahrgang 1996 DEUTSCHER KANU-VERBAND WIRTSCHAFTS- UND VERLAGS GMBH BERTAALLEE 8, 47055 DUISBURG INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 1996 1 Allgemeine Organisation, 16 Aus Vereinen und Verbänden Spitzenverbände, Leit- und Grundsatzartikel 17 Von der Jugend – für die Jugend 2 Kanurennsport 18 Ausbildung, Lehrgänge und Kurse 3 Kanuslalom 19 Termine und Veranstaltungen 4 Wildwasserrennsport 20 Terminänderungen und Berichtigungen 5 Kanusegeln 21 In eigener Sache 6 Kanupolo 22 Aus unserem Verlag 7 Marathonrennsport 23 Das interessiert auch Sie 8 Wasserwandern, Kanutouristik und 24 Boote und Ausrüstung Kanuabenteuer 25 Verloren, gefunden, gestohlen 9 Seekajak 26 Messen und Ausstellungen 10 Informationen zu Befahrungsregelungen 11 Berichte, Nachrichten und Notizen 27 Fernsehen, Film, Foto, Vorträge für Wanderfahrer 28 Leserbriefe 12 Naturberichte, Umwelt- und Gewässerschutz 29 Neu im Buchhandel 13 Sicherheit und Kanusport 30 Personalien 14 Sonstige Berichte 31 In memoriam 15 Verbandsnachrichten 32 Autorenverzeichnis der Hauptberichte 1 Allgemeine Organisation, Regattaausschreibung 1996 mit ReVes Kanuten auf dem Weg nach Atlanta3 ...135 Spitzenverbände, Leit- und ..................................................1 .....41 ReVes-Meldeprogramm ‘96: Grundsatzartikel Ausschreibung zur Frühjahrs-Kanu-Regatta Regattameldung per PC .............4 ...184 ..................................................3 ...134 Heft Seite Süddeutsche Kanurennsportmeisterschaften Ausschreibung -

Ye Intruders Beware: Fantastical Pirates in the Golden Age of Illustration

YE INTRUDERS BEWARE: FANTASTICAL PIRATES IN THE GOLDEN AGE OF ILLUSTRATION Anne M. Loechle Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of the History of Art Indiana University November 2010 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _________________________________ Chairperson, Sarah Burns, Ph.D. __________________________________ Janet Kennedy, Ph.D. __________________________________ Patrick McNaughton, Ph.D. __________________________________ Beverly Stoeltje, Ph.D. November 9, 2010 ii ©2010 Anne M. Loechle ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii Acknowledgments I am indebted to many people for the help and encouragement they have given me during the long duration of this project. From academic and financial to editorial and emotional, I was never lacking in support. I am truly thankful, not to mention lucky. Sarah Burns, my advisor and mentor, supported my ideas, cheered my successes, and patiently edited and helped me to revise my failures. I also owe her thanks for encouraging me to pursue an unorthodox topic. From the moment pirates came up during one of our meetings in the spring of 2005, I was hooked. She knew it, and she continuously suggested ways to expand the idea first into an independent study, and then into this dissertation. My dissertation committee – Janet Kennedy, Patrick McNaughton, and Beverly Stoeltje – likewise deserves my thanks for their mentoring and enthusiasm. Other scholars have graciously shared with me their knowledge and input along the way. David M. Lubin read a version of my third chapter and gave me helpful advice, opening up to me new ways of thinking about Howard Pyle in particular. -

Peer to Peer Resources

Peer To Peer Resources By Marcus P. Zillman, M.S., A.M.H.A. Executive Director – Virtual Private Library [email protected] This January 2009 column Peer To Peer Resources is a comprehensive list of peer to peer resources, sources and sites available over the Internet and the World Wide Web including peer to peer, file sharing, and grid and matrix search engines. The below list is taken from the peer to peer research section of my Subject Tracer™ Information Blog titled Deep Web Research and is constantly updated with Subject Tracer™ bots at the following URL: http://www.DeepWebResearch.info/ These resources and sources will help you to discover the many pathways available to you through the Internet for obtaining and locating peer to peer sources in todays rapidly changing data procurement society. This is a MUST information keeper for those seeking the latest and greatest peer to peer resources! Peer To Peer Resources: ALPINE Network - SourceForge: Project http://sourceforge.net/projects/alpine/ An Efficient Scheme for Query Processing on Peer-to-Peer Networks http://aeolusres.homestead.com/files/index.html angrycoffee.com http://www.AngryCoffee.com/ Azureus - Vuze Java Bittorrent Client http://azureus.sourceforge.net/ 1 January 2009 Zillman Column – Peer To Peer Resources http://www.zillmancolumns.com/ [email protected] © 2009 Marcus P. Zillman, M.S., A.M.H.A. BadBlue http://badblue.com/ Between Rhizomes and Trees: P2P Information Systems by Bryn Loban http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1182 -

Analysing the MUTE Anonymous File-Sharing System Using the Pi-Calculus

Analysing the MUTE Anonymous File-Sharing System Using the Pi-calculus Tom Chothia CWI, Kruislaan 413, 1098 SJ, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Abstract. This paper gives details of a formal analysis of the MUTE system for anonymous file-sharing. We build pi-calculus models of a node that is innocent of sharing files, a node that is guilty of file-sharing and of the network environment. We then test to see if an attacker can dis- tinguish between a connection to a guilty node and a connection to an innocent node. A weak bi-simulation between every guilty network and an innocent network would be required to show possible innocence. We find that such a bi-simulation cannot exist. The point at which the bi- simulation fails leads directly to a previously undiscovered attack on MUTE. We describe a fix for the MUTE system that involves using au- thentication keys as the nodes’ pseudo identities and give details of its addition to the MUTE system. 1 Introduction MUTE is one of the most popular anonymous peer-to-peer file-sharing systems1. Peers, or nodes, using MUTE will connect to a small number of other, known nodes; only the direct neighbours of a node know its IP address. Communication with remote nodes is provided by sending messages hop-to-hop across this overlay network. Routing messages in this way allows MUTE to trade efficient routing for anonymity. There is no way to find the IP address of a remote node, and direct neighbours can achieve a level of anonymity by claiming that they are just forwarding requests and files for other nodes. -

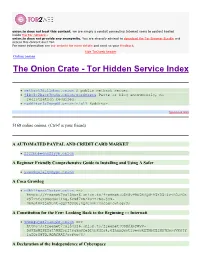

The Onion Crate - Tor Hidden Service Index Protected Onions Add New

onion.to does not host this content; we are simply a conduit connecting Internet users to content hosted inside the Tor network.. onion.to does not provide any anonymity. You are strongly advised to download the Tor Browser Bundle and access this content over Tor. For more information see our website for more details and send us your feedback. hide Tor2web header Online onions The Onion Crate - Tor Hidden Service Index Protected onions Add new nethack3dzllmbmo.onion A public nethack server. j4ko5c2kacr3pu6x.onion/wordpress Paste or blog anonymously, no registration required. redditor3a2spgd6.onion/r/all Redditor. Sponsored links 5168 online onions. (Ctrl-f is your friend) A AUTOMATED PAYPAL AND CREDIT CARD MARKET 2222bbbeonn2zyyb.onion A Beginner Friendly Comprehensive Guide to Installing and Using A Safer yuxv6qujajqvmypv.onion A Coca Growlog rdkhliwzee2hetev.onion ==> https://freenet7cul5qsz6.onion.to/freenet:USK@yP9U5NBQd~h5X55i4vjB0JFOX P97TAtJTOSgquP11Ag,6cN87XSAkuYzFSq-jyN- 3bmJlMPjje5uAt~gQz7SOsU,AQACAAE/cocagrowlog/3/ A Constitution for the Few: Looking Back to the Beginning ::: Internati 5hmkgujuz24lnq2z.onion ==> https://freenet7cul5qsz6.onion.to/freenet:USK@kpFWyV- 5d9ZmWZPEIatjWHEsrftyq5m0fe5IybK3fg4,6IhxxQwot1yeowkHTNbGZiNz7HpsqVKOjY 1aZQrH8TQ,AQACAAE/acftw/0/ A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace ufbvplpvnr3tzakk.onion ==> https://freenet7cul5qsz6.onion.to/freenet:CHK@9NuTb9oavt6KdyrF7~lG1J3CS g8KVez0hggrfmPA0Cw,WJ~w18hKJlkdsgM~Q2LW5wDX8LgKo3U8iqnSnCAzGG0,AAIC-- 8/Declaration-Final%5b1%5d.html A Dumps Market -

EP Elections 2014

EP Elections 2014 Biographies of new MEPs Please find the biographies of all the new MEPs elected to the 8th European Parliamentary term. The information has been collated from published sources and, in many cases, subject to translation from the native language. We will be contacting all MEPs to add to their biographical information over the summer, which will all be available on Dods People EU in due course. EU Elections 2014 Source: European Parliament- 1 - EP Overview (13/06/2014) List of countries: Austria Germany Poland Belgium Greece Portugal Bulgaria Hungary Romania Croatia Ireland Slovakia Cyprus Italy Slovenia Czech Latvia Spain Republic Denmark Lithuania Sweden United Estonia Luxembourg Kingdom Finland Malta France Netherlands EU Elections 2014 - 2 - Austria o People's Party (ÖVP) > EPP o Social Democratic Party (SPÖ) > S&D o Freedom Party (FPÖ) > NI o The Greens (GRÜNE) > Greens/EFA o New Austria (NEOS) > ALDE People’s Party (ÖVP) Claudia Schmidt (ÖVP, Austria) 26 April 1963 (FEMALE) Political: Councils/Public Bodies Member, Municipal Council, City of Salzburg 1999-; Chair, Austrian People's Party (ÖVP) Parliamentary Group, Salzburg Municipal Council 2004-09; Member, responsible for construction and urban development, Salzburg city government, 2009- Party posts: ÖVP: Vice-President, Salzburg, Member of the Board, Salzburg, Political Interest: Disability (social affairs) Personal: Non-political Career: Disability support institution (Lebenshilfe) Salzburg: Manager for special needs education 1989-1996, Officer responsible for -

Mit Gutem Recht Erinnern. Gedanken Zur Änderung Der Rechtlichen Rahmenbedingungen Des Kulturellen Erbes in Der Digitalen Welt

Paul Klimpel (Hg.) Mit gutem Recht erinnern Mit gutem Recht erinnern Gedanken zur Änderung der rechtlichen Rahmenbedingungen des kulturellen Erbes in der digitalen Welt Herausgegeben on Paul Klimpel Hamburg "ni ersit# Press $erlag der %taats& und "ni ersit'tsbibli!thek Hamburg (arl !n )ssietzk# *mpressum Bibli!gra,ische *nf!rmati!n der -eutschen .ati!nalbibli!thek -ie -eutsche .ati!nalbibli!thek erzeichnet diese Publikati!n in der -eutschen .ati!nalbibli!gra,ie/ detaillierte bibli!gra,ische -aten sind im *nternet über https122p!rtal.dnb.de2 abrufbar. )nline&3usgabe -ie )nline&3usgabe dieses Werkes ist eine )pen&Access&Publikati!n und ist auf den $erlags4ebseiten ,rei er,ügbar. -ie -eutsche Nati!nalbibli!thek hat die )nline&3usgabe archiviert. -iese ist dauerha,t auf dem 3rchi ser er der -eutschen .ati!nalbibli!thek (https122p!rtal.dnb.de2) er,ügbar. -)* 56.578962H"P.5:; Printausgabe *%+N <:;&=&<8=8>=&89&8 -as Werk einschlie?lich aller seiner @eile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. -as Werk steht unter der (reati e&(!mm!ns&Aizenz Namensnennung 8.6 *nternati!nal ((( +B 8.6C https122creati ec!mm!ns.!rg2licenses2b#28.62legalc!de.de). 3usgenommen !n der !ben genannten Aizenz sind @eileC Abbildungen und s!nstiges -rittmaterialC 4enn anders gekennzeichnet. Herausgeber1 Paul Klimpel (! ergestaltung1 Hamburg "ni ersit# Press (! erabbildung1 Dürgen KeiperC http122444.Ekeiper.de (FragmentC @*B Hanno er) -ruck und Bindung1 HansadruckC Kiel >65; Hamburg "ni ersit# PressC $erlag der %taats& und "ni ersit'tsbibli!thek Hamburg (arl !n )ssietzk#C Hamburg (-eutschland) http122hup.sub.uni&hamburg.de +es!nderer -ank gilt allen Autoren und der College Art Association. Ohne das große Engagement und die Geduld aller, die an diesem Buch mitgewirkt haben, hätte es nie entstehen können. -

Nachrichtenmagazin Der Piraten

Ausgabe 3 | April 2013 FLASCHENPOST Nachrichtenmagazin der Piraten UNSER TRAUM FÜR EUROPA! Piratenwelt | 38 KOMMUNALPOLITIK – QUO VADIS PIRATEN – Unsere EUROPA- Ein Piratenthema? Auf den Inhalt kommt es an KANDIDATEN Programm | 10 Debatten | 20 Piratenwelt | 34 Vorwort Herzlich willkommen zur dritten Flaschenpost Print-Ausgabe! Die Piraten sind eine internationale Bewegung. Seit der Gründung der ersten „Piratpartiet“ in Schweden im Jahr 2006 haben sich Piraten in über 60 Ländern rund um Globus zusammengefunden um sich gemeinsam unsere politischen Ziele zu vertreten. Mehr als die Hälfte all dieser Piratenparteien gründete sich in Europa und bilden schon heute eine starke Gemeinschaft. Nun schließen sich diese Parteien sogar unter einer Flagge zusammen, um gemeinsam ins Europäische Parlament einzuziehen. Natürlich brauchte es dafür ein auch gemeinsames Programm, dass die erfolgreichen Piratenabgeordneten dort vertreten können. Bereits in sechzehn Ländern haben die Piraten dieses gemeinsame Programm verabschiedet: Wir werden gemeinsam in ganz Europa für Bürgerbeteiligung, Open Government, Transparenz, Datenschutz, Flüchtlingspolitik, Urheberrecht, Freie Kultur und Freies Wissen und natürlich Netz- politik eintreten. Bis es soweit ist, steht allerdings erstmal der nächste Wahlkampf an; bis zur Europa- wahl am 25. Mai. Das Ziel ist ein gemeinsamer Wahlkampf, ein gemeinsamer Erfolg. Gefion Thürmer | Foto: CC-BY Tobias M. Eckrich Für Europa. Die Zukunft sieht gut aus - und mit dieser Ausgabe wollen wir unsere Leser an diesem zukünftigen Erfolg -

Tor: the Second-Generation Onion Router

Tor: The Second-Generation Onion Router Roger Dingledine Nick Mathewson Paul Syverson The Free Haven Project The Free Haven Project Naval Research Lab [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract vulnerable to a single hostile node recording traffic and later compromising successive nodes in the circuit and forcing We present Tor, a circuit-based low-latency anonymous them to decrypt it. Rather than using a single multiply en- communication service. This second-generation Onion crypted data structure (an onion) to lay each circuit, Tor Routing system addresses limitations in the original design. now uses an incremental or telescoping path-building de- Tor adds perfect forward secrecy, congestion control, direc- sign, where the initiator negotiates session keys with each tory servers, integrity checking, configurable exit policies, successive hop in the circuit. Once these keys are deleted, and a practical design for rendezvous points. Tor works subsequently compromised nodes cannot decrypt old traf- on the real-world Internet, requires no special privileges or fic. As a side benefit, onion replay detection is no longer kernel modifications, requires little synchronization or co- necessary, and the process of building circuits is more reli- ordination between nodes, and provides a reasonable trade- able, since the initiator knows when a hop fails and can then off between anonymity, usability, and efficiency. We briefly try extending to a new node. describe our experiences with an international network of Separation of “protocol cleaning” from anonymity: more than a dozen hosts. We close with a list of open prob- Onion Routing originally required a separate “applica- lems in anonymous communication.