Trent & Mersey Canal Character Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keele Research Repository

Keele~ UNIVERSITY This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights and duplication or sale of all or part is not permitted, except that material may be duplicated by you for research, private study, criticism/review or educational purposes. Electronic or print copies are for your own personal, non-commercial use and shall not be passed to any other individual. No quotation may be published without proper acknowledgement. For any other use, or to quote extensively from the work, permission must be obtained from the copyright holder/s. - I - URB.Ai.~ ADMINISTRATION AND HEALTH: A CASE S'fUDY OF HANLEY IN THE MID 19th CENTURY · Thesis submitted for the degree of M.A. by WILLIAM EDWARD TOWNLEY 1969 - II - CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT IV CHAPI'ER I The Town of Hanley 1 CHAPI'ER II Public Health and Local Government circa 1850 74 CHAPTER III The Struggle f'or a Local Board of Health. 1849-1854 164 CHAPT3R IV Incorporation 238 CP.:.API'ER V Hanley Town Council. 1857-1870 277 CHAPT&"t VI Reform in Retrospect 343 BIBLIOGRAPHY 366 - III - The Six Tot,J11s facing page I Hanley 1832 facing page 3 Hanley 1857 facing page 9~ Hanley Township Boundaries facing page 143 The Stoke Glebeland facing page 26I - IV - ABSTRACT The central theme of this study is the struggle, under the pressure of a deteriorating sanitary situation to reform the local government structure of Hanley, the largest of the six towns of the North Staffordshire potteries. The first chapter describes the location of the town and considers its economic basis and social structure in the mid nineteenth century, with particular emphasis on the public role of the different social classes. -

Stoke on Trent and the Potteries from Stone | UK Canal Boating

UK Canal Boating Telephone : 01395 443545 UK Canal Boating Email : [email protected] Escape with a canal boating holiday! Booking Office : PO Box 57, Budleigh Salterton. Devon. EX9 7ZN. England. Stoke on Trent and the Potteries from Stone Cruise this route from : Stone View the latest version of this pdf Stoke-on-Trent-and-the-Potteries-from-Stone-Cruising-Route.html Cruising Days : 4.00 to 0.00 Cruising Time : 11.50 Total Distance : 18.00 Number of Locks : 24 Number of Tunnels : 0 Number of Aqueducts : 0 The Staffordshire Potteries is the industrial area encompassing the six towns, Tunstall, Burslem, Hanley, Stoke, Fenton and Longton that now make up the city of Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, England. With an unrivalled heritage and very bright future, Stoke-on-Trent (affectionately known as The Potteries), is officially recognised as the World Capital of Ceramics. Visit award winning museums and visitor centres, see world renowned collections, go on a factory tour and meet the skilled workers or have a go yourself at creating your own masterpiece! Come and buy from the home of ceramics where quality products are designed and manufactured. Wedgwood, Portmeirion, Aynsley, Emma Bridgewater, Burleigh and Moorcroft are just a few of the leading brands you will find here. Search for a bargain in over 20 pottery factory shops in Stoke-on-Trent or it it's something other than pottery that you want, then why not visit intu Potteries? Cruising Notes Day 1 As you are on the outskirts of Stone, you may like to stay moored up and visit the town before leaving. -

Row 3169391 Od.Pdf

Order Decision Site visit made on 2 August 2017 by Grahame Kean B.A. (Hons), PgCert CIPFA, Solicitor HCA an Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Decision date: 29 November 2017 Order Ref: ROW/3169391 This Order is made under Section 118 of the Highways Act 1980 (the 1980 Act) and is known as the Derby City Council Megaloughton Lane, Extinguishment Order 2014. The Order is dated 6 March 2014 and proposes to extinguish the public right of way shown on the Order plan and described in the Order Schedule. There were five objections outstanding when Derby City Council submitted the Order to the Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs for confirmation. Summary of Decision: The Order is not confirmed Procedural Matter 1. Network Rail was granted a Temporary Traffic Regulation Order to commence on 11 January 2017 to close the crossing in order to carry out track works. The effect of the temporary order ended on 30th June 2017. However when I visited, the Megaloughton Lane level crossing was still closed and fenced off. 2. Derby City Council, the order making authority (the Council) was requested to supply details of the authority under which it is currently closed. The Council confirmed that the crossing has been closed without any legal authority. It also appears from its statement that, following the making of the Order, Network Rail had closed off access to the line without the Council’s consent. 3. I was thus unable to walk the whole of the existing route but viewed the crossing through metal railings placed across each side. -

Part 1.7 Trent Valley Washlands

Part One: Landscape Character Descriptions 7. Trent Valley Washlands Landscape Character Types • Lowland Village Farmlands ..... 7.4 • Riverside Meadows ................... 7.13 • Wet Pasture Meadows ............ 7.9 Trent Valley Washlands Character Area 69 Part 1 - 7.1 Trent Valley Washlands CHARACTER AREA 69 An agricultural landscape set within broad, open river valleys with many urban features. Landscape Character Types • Lowland Village Farmlands • Wet Pasture Meadows • Riverside Meadows "We therefore continue our course along the arched causeway glancing on either side at the fertile meadows which receive old Trent's annual bounty, in the shape of fattening floods, and which amply return the favour by supporting herds of splendid cattle upon his water-worn banks..." p248 Hicklin; Wallis ‘Bemrose’s Guide to Derbyshire' Introduction and tightly trimmed and hedgerow Physical Influences trees are few. Woodlands are few The Trent Valley Washlands throughout the area although The area is defined by an constitute a distinct, broad, linear occasionally the full growth of underlying geology of Mercia band which follows the middle riparian trees and shrubs give the Mudstones overlain with a variety reaches of the slow flowing River impression of woodland cover. of fluvioglacial, periglacial and river Trent, forming a crescent from deposits of mostly sand and gravel, Burton on Trent in the west to Long Large power stations once to form terraces flanking the rivers. Eaton in the east. It also includes dominated the scene with their the lower reaches of the rivers Dove massive cooling towers. Most of The gravel terraces of the Lowland and Derwent. these have become Village Farmlands form coarse, decommissioned and will soon be sandy loam, whilst the Riverside To the north the valley rises up to demolished. -

The Trent & Mersey Canal Conservation Area Review

The Trent & Mersey Canal Conservation Area Review March 2011 stoke.gov.uk CONTENTS 1. The Purpose of the Conservation Area 1 2. Appraisal Approach 1 3. Consultation 1 4. References 2 5. Legislative & Planning Context 3 6. The Study Area 5 7. Historic Significant & Patronage 6 8. Chatterley Valley Character Area 8 9. Westport Lake Character Area 19 10. Longport Wharf & Middleport Character Area 28 11. Festival Park Character Area 49 12. Etruria Junction Character Area 59 13. A500 (North) Character Area 71 14. Stoke Wharf Character Area 78 15. A500 (South) Character Area 87 16. Sideway Character Area 97 17. Trentham Character Area 101 APPENDICES Appendix A: Maps 1 – 19 to show revisions to the conservation area boundary Appendix B: Historic Maps LIST OF FIGURES Fig. 1: Interior of the Harecastle Tunnels, as viewed from the southern entrance Fig. 2: View on approach to the Harecastle Tunnels Fig. 3: Cast iron mile post Fig. 4: Double casement windows to small building at Harecastle Tunnels, with Staffordshire blue clay paviours in the foreground Fig. 5: Header bond and stone copers to brickwork in Bridge 130, with traditionally designed stone setts and metal railings Fig. 6: Slag walling adjacent to the Ravensdale Playing Pitch Fig. 7: Interplay of light and shadow formed by iron lattice work Fig. 8: Bespoke industrial architecture adds visual interest and activity Fig. 9: View of Westport Lake from the Visitor Centre Fig. 10: Repeated gable and roof pitch details facing towards the canal, south of Westport Lake Road Fig. 11: Industrial building with painted window frames with segmental arches Fig. -

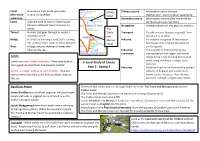

A Local Study of Canals Year 3

Canal A canal is a man-made waterway. Caldon Primary source Information about the past Man-made A canal or aqueduct. Canal that has first –hand or direct experience. waterway Secondary source Information created after the event by Locks A device used to raise or lower boats someone who was not there. between different levels of water on Navigation Finding a way from one place to another. canals. The Tunnel A route that goes through or under a Trent Transport To take or carry (people or goods) from mountain or hill. and one place to another. Bridge A structure carrying a road, path, railway, Mersey Industry An industry is a group of factories or etc. across a river, road, or other obstacle. Canal businesses that produce the same (or River A large, natural channel of water that similar) goods. flows to the sea. Industrial The changes in manufacturing and revolution transportation that began with fewer Canals things being made by hand but instead made using machines in larger-scale Canals are man- made waterways. They were built to A Local Study of Canals carry goods by boat from one place to another. factories. Year 3 - Spring 2 Potteries Stoke-on-Trent is the home of the pottery A river is a large, natural stream of water. They are industry in England and is commonly formed when rain falls in the hills and flows down to known as the Potteries. This includes the sea. Burslem, Tunstall, Longton and Fenton. Significant People There are two canals that run through Stoke-on-Trent: The Trent and Mersey Canal and the Caldon Canal. -

Memorials of Old Staffordshire, Beresford, W

M emorials o f the C ounties of E ngland General Editor: R e v . P. H. D i t c h f i e l d , M.A., F.S.A., F.R.S.L., F.R.Hist.S. M em orials of O ld S taffordshire B e r e s f o r d D a l e . M em orials o f O ld Staffordshire EDITED BY REV. W. BERESFORD, R.D. AU THOft OF A History of the Diocese of Lichfield A History of the Manor of Beresford, &c. , E d i t o r o f North's .Church Bells of England, &■V. One of the Editorial Committee of the William Salt Archaeological Society, &c. Y v, * W ith many Illustrations LONDON GEORGE ALLEN & SONS, 44 & 45 RATHBONE PLACE, W. 1909 [All Rights Reserved] T O T H E RIGHT REVEREND THE HONOURABLE AUGUSTUS LEGGE, D.D. LORD BISHOP OF LICHFIELD THESE MEMORIALS OF HIS NATIVE COUNTY ARE BY PERMISSION DEDICATED PREFACE H ILST not professing to be a complete survey of Staffordshire this volume, we hope, will W afford Memorials both of some interesting people and of some venerable and distinctive institutions; and as most of its contributors are either genealogically linked with those persons or are officially connected with the institutions, the book ought to give forth some gleams of light which have not previously been made public. Staffordshire is supposed to have but little actual history. It has even been called the playground of great people who lived elsewhere. But this reproach will not bear investigation. -

December 2019 Derby City Council Rights of Way Improvement Plan

Agenda Item 8 Report for the Derby and Derbyshire Local Access Forum 6th December 2019 Derby City Council Rights of Way Improvement Plan Ray Brown, Senior Planning Officer, Planning Division, Derby City Council General service The Rights of Way service, within the Planning Division, continues to carry out the network management side of the rights of way function including the work on updating the definitive map and dealing with public path orders. The Highways Maintenance service continues to carry out the rights of way maintenance and enforcement function. Definitive map and path orders As stated in previous reports, work continues to be carried out towards the production of the legal event modification orders that are required to bring the definitive map areas covering Derby up to date. Work continues on the drafting of orders for the city. The service also continues to process public path order applications around the city. Major path schemes The Darley Park Cycleway. The cycleway, which will run through Darley Park, north to south, will be part hard surfaced as standard and part elevated timber boardwalk because of poor drainage. Construction work is still progressing. Derby to Nottingham Cycle Route. The Derby section of this strategic route will follow the Spondon section of the former Derby Canal. The scheme planning is ongoing. A connection to the Bennerley Viaduct to the north would be investigated at some point but only after the main route has been constructed. Derwent Valley Cycleway. This is a Highways England led cycleway scheme linking Haslams Lane, Derby and Little Eaton. There have been some changes to the management arrangements of the project and work on the scheme continues. -

Strategic Flood Risk Assessment Executive Summary

North Staffordshire Strategic Flood Risk Assessment for Local Development Framework Level 1 Executive Summary July 2008 Halcrow Group Limited North Staffordshire Strategic Flood Risk Assessment for Local Development Framework Level 1 Executive Summary July 2008 Halcrow Group Limited Halcrow Group Limited Lyndon House 62 Hagley Road Edgbaston Birmingham B16 8PE Tel +44 (0)121 456 2345 Fax +44 (0)121 456 1569 www.halcrow.com Halcrow Group Limited has prepared this report in accordance with the brief from Gloucestershire County Council, for their sole and specific use. Any other persons who use any information contained herein do so at their own risk. © Halcrow Group Limited 2008 North Staffordshire Strategic Flood Risk Assessment for Local Development Framework Level 1 Executive Summary Contents Amendment Record This report has been issued and amended as follows: Issue Revision Description Date Signed 1 0 Executive Summary 08/07/2008 RD Prepared by: Caroline Mills Final: 08/07/08 Checked by: Beccy Dunn Final: 08/07/08 Approved by: John Parkin Final: 08/07/08 Level 1 Strategic Flood Risk Assessment: Executive Summary Gloucestershire County Council This page is left intentionally blank Level 1 Strategic Flood Risk Assessment: Executive Summary Gloucestershire County Council 1 Executive Summary 1.1 Background In September 2007 Stoke-on-Trent City Council and Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council commissioned Halcrow to produce a Level 1 Strategic Flood Risk Assessment (SFRA). Figure 1: North Staffordshire SFRA Study Area The SFRA has been prepared to support the application of the Sequential Test (by the Councils) outlined in Planning Policy Statement 25: Development and Flood Risk (PPS25), and to provide information and advice in relation to land allocations and development control. -

Key Wildlife Sites and Species of Interest in Derby

Derby Riverside Gardens Fly Agaric Key wildlife sites and species of interest in Derby Derby Council House Moonwort Darley Park City centre inset Allestree Park Allestree Park and lake Toothwort proposed Local Nature Reserve T8 To Darley Abbey Park River Discovered in 2001 A6 to St. Alkmund 1 kilometre Birch woods, Derwent Spring Beauty in grass 's Way Lunch-hour birdwatching spot. - Allestree Park Matlock Ducks, gulls, swans, geese Allestree Park T8 Industrial A52 to Nottingham and M1 Hobby Railway line P Museum DERBY CITY COUNCIL P To Markeaton Full River Darley Park. Brook walkway T7 Darwin Canada Goose P T1 Street Only two sites known in Derby Alder trees on Place A38 to Cathedral Road Cathedral W1 Mansfield Great for wildlife river corridor 's Gate P Iron Gate Magistrates St. Mary N A608 to Court Chaddesden Wood P WC Derwent Local Nature Reserve Heanor Bristly Oxtongue Bold Lane Assembly Derwent Rooms Street P Bass’s Council Riverside Allestree Little Ringed Plover St Werburgh’s Recreation Darley Sadler Gate House Gardens T7 Church Market Place Ground Abbey T4 Oakwood Friar Gate + Corn MarketGuildhall Crown and To Alvaston Park Markeaton Park Strand Theatre County Court 2.5 kilometres River corridors, lakes W2 Museum t Morledge late summer P e and Library e tr Bus S WC rt T8 WardwickVictoria be Station Street Al P P W3 T5 Former railway line Street A52 to Darley St. Peter's The Cock Pitt R Breeds near River Station Ashbourne WC Abbey St Werburgh’s Church East Derwent corridor Market Approach Park R Eagle Chaddesden Street Shopping -

69: Trent Valley Washlands Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 69: Trent Valley Washlands Area profile: Supporting documents www.naturalengland.org.uk 1 National Character 69: Trent Valley Washlands Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper1, Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention3, we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas (NCAs). These are areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform their decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental Opportunity (SEOs) are suggested, which draw on this integrated information. The SEOs offer guidance on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. 1 The Natural Choice: Securing the Value of Nature, Defra NCA profiles are working documents which draw on current evidence and (2011; URL: www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/cm80/8082/8082.pdf) 2 knowledge. -

Derby's Locally Listed Buildings

City of Derby City of Derby Local List Local List CITY OF DERBY Introduction This list identifies buildings and other structures within Derby which are considered to have some local importance, either from an architectural or historic viewpoint. The list has been revised from the previously published list of 1993, following a public consultation period in 2007. Along with the review of the existing list, people were also invited to nominate new buildings for inclusion on the revised list. The new list was approved by Council Cabinet in July 2010 and is organised in alphabetical order by ward. None of the buildings or structures are included in Derby’s Statutory List of Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest. Some may, in the future, be considered worthy of national listing. The local list seeks to include buildings which are of merit in their own right, those which are worthy of group value in the street scene and any other feature which is considered to be worthy of conservation because it makes a positive contribution to the local environment. The list contains examples of different architectural styles from many periods, including those of relatively recent origins. It does not include locally important buildings that are located within any of the 15 conservation areas in Derby, as these buildings are afforded greater protection through the planning control process. The value of publishing a local list is that a watching brief can be kept on these buildings or structures and they can be taken into account in the town planning process. Inclusion in the list, however, does not afford any additional statutory protection or grant aid, but it is the Council’s intention that every reasonable effort will be made to conserve those buildings and structures of local importance to benefit the city as a whole.