Staffordshire Pottery and Its History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Listed Buildings in Newcastle-Under-Lyme Summary List

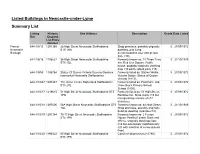

Listed Buildings in Newcastle-under-Lyme Summary List Listing Historic Site Address Description Grade Date Listed Ref. England List Entry Number Former 644-1/8/15 1291369 28 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Shop premises, possibly originally II 27/09/1972 Newcastle ST5 1RA dwelling, with living Borough accommodation over and at rear (late c18). 644-1/8/16 1196521 36 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Formerly known as: 14 Three Tuns II 21/10/1949 ST5 1QL Inn, Red Lion Square. Public house, probably originally dwelling (late c16 partly rebuilt early c19). 644-1/9/55 1196764 Statue Of Queen Victoria Queens Gardens Formerly listed as: Station Walks, II 27/09/1972 Ironmarket Newcastle Staffordshire Victoria Statue. Statue of Queen Victoria (1913). 644-1/10/47 1297487 The Orme Centre Higherland Staffordshire Formerly listed as: Pool Dam, Old II 27/09/1972 ST5 2TE Orme Boy's Primary School. School (1850). 644-1/10/17 1219615 51 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire ST5 Formerly listed as: 51 High Street, II 27/09/1972 1PN Rainbow Inn. Shop (early c19 but incorporating remains of c17 structure). 644-1/10/18 1297606 56A High Street Newcastle Staffordshire ST5 Formerly known as: 44 High Street. II 21/10/1949 1QL Shop premises, possibly originally build as dwelling (mid-late c18). 644-1/10/19 1291384 75-77 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Formerly known as: 2 Fenton II 27/09/1972 ST5 1PN House, Penkhull street. Bank and offices, originally dwellings (late c18 but extensively modified early c20 with insertion of a new ground floor). 644-1/10/20 1196522 85 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Commercial premises (c1790). -

Charles Darwin: a Companion

CHARLES DARWIN: A COMPANION Charles Darwin aged 59. Reproduction of a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron, original 13 x 10 inches, taken at Dumbola Lodge, Freshwater, Isle of Wight in July 1869. The original print is signed and authenticated by Mrs Cameron and also signed by Darwin. It bears Colnaghi's blind embossed registration. [page 3] CHARLES DARWIN A Companion by R. B. FREEMAN Department of Zoology University College London DAWSON [page 4] First published in 1978 © R. B. Freeman 1978 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher: Wm Dawson & Sons Ltd, Cannon House Folkestone, Kent, England Archon Books, The Shoe String Press, Inc 995 Sherman Avenue, Hamden, Connecticut 06514 USA British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Freeman, Richard Broke. Charles Darwin. 1. Darwin, Charles – Dictionaries, indexes, etc. 575′. 0092′4 QH31. D2 ISBN 0–7129–0901–X Archon ISBN 0–208–01739–9 LC 78–40928 Filmset in 11/12 pt Bembo Printed and bound in Great Britain by W & J Mackay Limited, Chatham [page 5] CONTENTS List of Illustrations 6 Introduction 7 Acknowledgements 10 Abbreviations 11 Text 17–309 [page 6] LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Charles Darwin aged 59 Frontispiece From a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron Skeleton Pedigree of Charles Robert Darwin 66 Pedigree to show Charles Robert Darwin's Relationship to his Wife Emma 67 Wedgwood Pedigree of Robert Darwin's Children and Grandchildren 68 Arms and Crest of Robert Waring Darwin 69 Research Notes on Insectivorous Plants 1860 90 Charles Darwin's Full Signature 91 [page 7] INTRODUCTION THIS Companion is about Charles Darwin the man: it is not about evolution by natural selection, nor is it about any other of his theoretical or experimental work. -

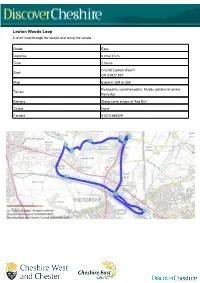

Lawton Woods Loop a Short Loop Through the Woods and Along the Canals

Lawton Woods Loop A short loop through the woods and along the canals. Grade Easy Distance 6 kms/3.5 m Time 2 hours Church Lawton church Start GR SJ822 557 Map Explorer 258 or 268 Field paths, canal towpaths. Muddy patches in winter. Terrain Fairly flat. Barriers Steep canal bridge at Red Bull. Toilets None Contact 01270 686029 Route Details The name Lawton originates in the Lawton family with its family crest being the head of a bleeding wolf. Local legend talks about a man saving the Earl of Chester from being killed by a wolf. This act of bravery took place in about 1200, and to repay the deed, this man was given an area of land between Congleton and Sandbach. The one thousand acre estate became the Parish of Lauton, (later Church Lawton), and is recorded in the Domesday Survey of 1086. The family crest can be found in the church. Lawton Hall, the country seat, of the Lawton family was built in the 17th century, but was almost destroyed by a fire in 1997. During the First World War the hall was used as a hospital, until this time it was still the Lawton family seat. Later it became Lawton Hall school which closed in 1986. Today it has been renovated into private dwellings. Iron smelting took place in the woods during the late 1600’s early 1700’s. Coal mining took place in nearby Kidsgrove and some of the mines extended into the Church Lawton / Red Bull area. The Trent and Mersey canal is linked to the Macclesfield canal at the Harding’s Wood Junction. -

The Harecastle Tunnel the Harecastle Tunnel

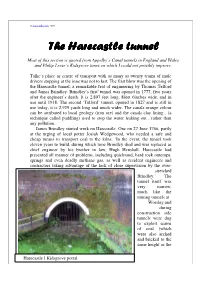

© www.talke.info 2008 The Harecastle tunnel Most of this section is quoted from Appelby’s Canal tunnels in England and Wales and Philip Leese’s Kidsgrove times on which I could not possibly improve. Talke’s place as centre of transport with as many as twenty teams of mule drivers stopping at the inns was not to last. The first blow was the opening of the Harecastle tunnel, a remarkable feat of engineering by Thomas Telford and James Brindley. Brindley’s first t tunnel was opened in 1777, five years after the engineer’s death. It is 2,897 feet long, 8feet 6inches wide, and in use until 1918. The second ‘Telford’ tunnel, opened in 1827 and is still in use today, it is 2,929 yards long and much wider. The canals orange colour can be attributed to local geology (iron ore) and the canals clay lining , (a technique called puddling) used to stop the water leaking out , rather than any pollution. James Brindley started work on Harecastle One on 27 June 1766, partly at the urging of local potter Josiah Wedgewood, who needed a safe and cheap means to transport coal to the kilns. ‘In the event, the tunnel took eleven years to build, during which time Brindley died and was replaced as chief engineer by his brother in law, Hugh Henshall. Harecastle had presented all manner of problems, including quicksand, hard rock outcrops, springs and even deadly methane gas, as well as resident engineers and contractors taking advantage of the lack of close supervision by the over- stretched Brindley.’ The tunnel itself was very narrow, much like the mining tunnels at Worsley,and during construction side tunnels were dug to exploit seams of coal (which were also arched and bricked to the same height as the Harecastle I Kidsgrove portal © www.talke.info 2008 main tunnel).’ One local legend states that there is an underground wharf just within the Kidsgrove entrance to load this coal. -

NEWCASTLE- UNDER-LYME Stoke -On-Trent Hanley Burslem Tunstall

C O G AD O O G N U T A D A O T D U FEGG HAYES ROAD Fegg Hayes EN F N SH unnels T IEL R S D E D E I A O R C R P T LANE N OA A I C C D V H ON E R L E GT B O S O IN N EVA AD L A RIV N A G R AD RG R T E VE O RO E L C N O A E UE RIDG A E A R R N Y L D D U T UE P EN A N LO O S CDRIVE A AV O C D S IA V N V H GE N EL D E EE S H RO Line Houses O R E N IG AD ZC G H E L AD R L A O L C T H O R L J I R O O P L H S Y H T B A A R EA R H E R G K AN D D I D V U E L R U C E W E I B E CHEL GR S A L RD A N B O ER C A T T W H A E G G R ORD LISH T T S ORD RD R C O H OW H LE E SHELF E B RE E C N N N A E R A Y M CHEL ARDLEY DRO LA R R E EN W O T AD R A L IN R I O H D A H L A AZ D OA V N J A A I EL N R D Y H E E E D U R R A W G R AR LH W Y STR D W N M Talke L R D A R H Sandyford U 4 L O O I A O R H PL EA T T E A 3 OO FI E K G H ERSF D IC I ND T CROFTROAD D E S STA RN B A G E W H BA Whitfield A U Dunkirk O S B Parrot’s Drumble R Pits B E H C R L A S C O D Ravenscliffe O H O C D Valley R R Great Chell D U K A O OA Nature L E R A R L A S B A N I T D L E AK B L E E A D F D T PITL L O E E L R Y A O N O Y R O B Reserve E I R S N T G R R R N A R J O H A R Monks-Neil Park M O D D S Bathpool L E E L S A O ' EL’S E B D A P RI L A E ND D E N LEY A A L W N H A Pitts V I L Park Y H E A T 5 A T Little N Y R C 2 V A I E S Hill 7 E U OAD T M CORNHILL R S B 2 N S E E A N M SO U R Holly Wall O C N Chell E DR T S 7 E T D B A N OA A H Y 2 R Clanway S K R D W A U N I 5 Y O BA OAD G H W A B RINK T EYR O E G A WJO T SP C L A H U ES Sports K T N H O E R Y A H I N K S N W N B O N E A -

The Implementation and Impact of the Reformation in Shropshire, 1545-1575

The Implementation and Impact of the Reformation in Shropshire, 1545-1575 Elizabeth Murray A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts United Faculty of Theology The Melbourne College of Divinity October, 2007 Abstract Most English Reformation studies have been about the far north or the wealthier south-east. The poorer areas of the midlands and west have been largely passed over as less well-documented and thus less interesting. This thesis studying the north of the county of Shropshire demonstrates that the generally accepted model of the change from Roman Catholic to English Reformed worship does not adequately describe the experience of parishioners in that county. Acknowledgements I am grateful to Dr Craig D’Alton for his constant support and guidance as my supervisor. Thanks to Dr Dolly Mackinnon for introducing me to historical soundscapes with enthusiasm. Thanks also to the members of the Medieval Early Modern History Cohort for acting as a sounding board for ideas and for their assistance in transcribing the manuscripts in palaeography workshops. I wish to acknowledge the valuable assistance of various Shropshire and Staffordshire clergy, the staff of the Lichfield Heritage Centre and Lichfield Cathedral for permission to photograph churches and church plate. Thanks also to the Victoria & Albert Museum for access to their textiles collection. The staff at the Shropshire Archives, Shrewsbury were very helpful, as were the staff of the State Library of Victoria who retrieved all the volumes of the Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological Society. I very much appreciate the ongoing support and love of my family. -

Fast Fossils Carbon-Film Transfer on Saggar-Fired Porcelain by Dick Lehman

March 2000 1 2 CERAMICS MONTHLY March 2000 Volume 48 Number 3 “Leaves in Love,” 10 inches in height, handbuilt stoneware with abraded glaze, by Michael Sherrill, Hendersonville, North FEATURES Carolina. 34 Fast Fossils 40 Carbon-Film Transfer on Saggar-Fired Porcelain by Dick Lehman 38 Steven Montgomery The wood-firing kiln at Buck Industrial imagery with rich texture and surface detail Pottery, Gruene, Texas. 40 Michael Sherrill 62 Highly refined organic forms in porcelain 42 Rasa and Juozas Saldaitis by Charles Shilas Lithuanian couple emigrate for arts opportunities 45 The Poetry of Punchong Slip-Decorated Ware by Byoung-Ho Yoo, Soo-Jong Ree and Sung-Jae Choi by Meghen Jones 49 No More Gersdey Borateby JejfZamek Why, how and what to do about it 51 Energy and Care Pit Firing Burnished Pots on the Beach by Carol Molly Prier 55 NitsaYaffe Israeli artist explores minimalist abstraction in vessel forms “Teapot,” approximately 9 inches in height, white 56 A Female Perspectiveby Alan Naslund earthenware with under Female form portrayed by Amy Kephart glazes and glazes, by Juozas and Rasa Saldaitis, 58 Endurance of Spirit St. Petersburg, Florida. The Work of Joanne Hayakawa by Mark Messenger 62 Buck Pottery 42 17 Years of Turnin’ and Burnin’ by David Hendley 67 Redware: Tradition and Beyond Contemporary and historical work at the Clay Studio “Bottle,” 7 inches in height, wheel-thrown porcelain, saggar 68 California Contemporary Clay fired with ferns and sumac, by The cover:“Echolalia,” San Francisco invitational exhibition Dick Lehman, Goshen, Indiana. 29½ inches in height, press molded and assembled, 115 Conquering Higher Ground 34 by Steven Montgomery, NCECA 2000 Conference Preview New York City; see page 38. -

STAFFORDSHIRE. BEE 645 11'Arkes Mrs

TRADES DIRECTORY.] STAFFORDSHIRE. BEE 645 11'arkes Mrs. Hannah, Stoney lane, Pigott Chas.Norton Canes,CannockS.O Province Richard, New street, Quarry West Bromwich Pike J oseph, 8 Danks street, Burnt Bank, 'Brierley Hill :l'arkes J. 70 Green la. Birchills,Walsll tree, Tipton Pugh John, 171 Normacot rd.Longton 'Parkes James, Seighford, Stafford Pilkington Mrs. Elizabeth, 17 St. Pugh John, 16 Richard street south, ::Parkes J. 164 Holyhead rd. Wednsbry Paul's street west, Burton West Bromwich Parkes Joseph, 40 Waterloo st. Tipton Pilkington Geo. H. 31 Stafford st.Wlsl Pullen Thos. 34 Park street, Stoke 'Parkes M. New Invention, W'hmptn Pim & Co. Bucknall, Stoke Purnell Jn. Hy. I Lower green,Tipton :l'arkes Noah, Powke lane, Black Pinner E.101 Leek rd.Smallthrn.Stoke Purslow William, Walsall Wood,Walsll Heath, Birmingham Piper Joseph, Kiddemore Grn.Stafford Quarry Edwd. Buckpool, Brierley Hill !Parr Mrs. L. 12 Wedgwood street, Piper "\V. H. Newton st. We.Brmwcb Radford George, wo Penkhull New rd. Wolstanton, Stoke Pitt A. J. 74a, Park lane west, Tipton Penkhull, Stoke Parr Ralph, 6 Rathbone st. Tunstall Pitt John Hy. Moxley, Wednesbury Rae Mrs. Agnes, I Oak street, Burton !Parslow George, Milton, Stoke Pitt Samuel Thomas, Wordsley,Strbdg Ralley S.14'5 Gt. Bridge st.W.Brmwch Parsons E.Brickhouse la. We. Brmwch Plant B. Wimblebury, Hednesford S.O Ralph Ohas. 77 Oxford st. W'hmpton :Parsons Harry, I Doxey road, •Stafford Plant Mrs. Eliza, 34a, Upper Church Randall Charles, 83 Coleman street, Parton Enoch, 20 Lowe st. W'hamptn lane, Tipton Whitmore Reans, Wolverhampton i'ascall Jn. -

STAFFORDSHIRE. J • out :Boulton Mrs

TRADES- DIRECTORY. STAFFORDSHIRE. J • OUT :Boulton Mrs. Mary Ellen, 49 Station OFFICE FITTERS. fOIL SHEET MANUFACTURSr road, Stone See Shop & Office Fitters. Bradbum Wm. W ednesfid. W'hmptn Conyers Miss Annie, 7 .Alexander st. Bradbury Jsph. C. Edward st. Ston& "\VolveThampton OIL DEALERS. Brown lL E. & Co. Bell st. Wolvrhptn J ohnson Mrs. L. 6 Southbank st.Leek See Lamp & Oil Dealers. Dawes Ed ward George, Melbourne OIL MANUFACTURERS. Street works, Melbourne street, NURSING INSTITUTIONS & Wolverhampton Gaunt & Hickman, British oil works, HOMES. Horseley fields; offices, Waterloo OMNIBUS PROPRIETORS. Burton-on-Trent (t\'llss E. Goodall, road north, Wolverhampton See Job Masters. matron), 59 Union street, Burton Hood R. W. & Co. Sandwell r9ad, Cruso NursingAs.sociation(E.Challinor, West Bromwich OPTICIANS. sec.), 10 Derby street, Leek Keys William Hall, Hall end, Church Blackham H. 44 Lichfield st.W'hamptn Diamond Jnbilee Nurses' Home (A. P. lane, We~t Bromwich Corner Wm. Thomas, 6 .Arcade,Walsall Tiley, sec.), Newcastle st. Burslem Lees Silas, Oakeswell end, W ednsbry Franks .Aubrey, 55 Lichfield st. W'hpta. Hanley Nursing Society' (Miss Elizh. Smallman William Frederick & Son, Franks Benn, 39 Piccadilly, Hanley Cook, nurse in charge), 39 Lich Paradise street, West Bromwich Gibbons Walter, 73 Bradford st.W'sal1. field street, Hanley Walton Thomas & Co. Park Lane Higgs Alfred, 243 Horninglow rd.Brtn Lichfield Victoria Nursing Home (Miss works, Park lane east, Tipton Hinkley John, 3 Lad lane, Ironma-r- Emilie Smythe, lady supt'lrintendt.), ket, N ewcastl~ Sandford street, Lichfield Vacuum Oil Company Ltd. (Howard Jackson Charles, 2 Market pl. Burtoa. North Staffordshire Nurses' Institu B. -

PRESS RELEASE New Lease of Life for Burslem School Of

PRESS RELEASE New lease of life for Burslem School of Art Burslem School of Art, in the heart of the Mothertown, will soon be embarking on a new chapter in its illustrious history. From September 2016, 200 students from Haywood Sixth Form Academy will move into the newly refurbished grade II listed building to enjoy purpose-built facilities. A state-of-the-art design enterprise suite will be used for engineering product design and textiles. A specialist photography suite will house its own dark room and Apple Macs to enable students to learn digital photography skills. An ICT ‘window on the world’ room and specialist computing laboratory will provide students with leading-edge computer equipment and there will also be a specialist science lab and language lab. Students will develop their artistic talents in the magnificent art room, with its huge windows and perfect lighting for artwork, following in the footsteps of the Burslem School of Art’s prestigious alumni, including Clarice Cliff, Susie Cooper and William Moorcroft. The Burslem School of Art Trust carried out a refurbishment of the building in 2000 and has developed and delivered many arts events, projects and activities over the past fifteen years, working with diverse communities and artists. Now, Haywood Sixth Form Academy is working closely with the Trust to form a partnership that will build on its fantastic work and secure the future of this beautiful building. Carl Ward, Executive Headteacher, said: “Haywood Sixth Form Academy is becoming as popular as I had hoped when many parents and students asked if we would consider opening, just a few years ago. -

The Kangaroo Island China Stone and Clay Company and Its Forerunners

The Kangaroo Island China Stone and Clay Company and its Forerunners ‘There’s more stuff at Chinatown – more tourmalines, more china clay, silica, and mica – than was ever taken out of it’. Harry Willson in 1938.1 Introduction In September 2016 a licence for mineral exploration over several hectares on Dudley Peninsula, Kangaroo Island expired. The licensed organisation had searched for ‘ornamental minerals’ and kaolin.2 Those commodities, tourmalines and china stone, were first mined at this site inland and west of Antechamber Bay some 113 years ago. From March 1905 to late 1910, following the close of tourmaline extraction over 1903-04, the Kangaroo Island China Stone and Clay Company mined on the same site south-east of Penneshaw, and operated brick kilns within that township. This paper outlines the origin and short history of that minor but once promising South Australian venture. Tin and tourmaline The extensive deposits inadvertently discovered during the later phase of tourmaline mining were of china (or Cornish) stone or clay (kaolin), feldspar (basically aluminium silicates with other minerals common in all rock types), orthoclase (a variant of feldspar), mica, quartz, and fire-clay. The semi-precious gem tourmaline had been chanced upon in a corner trench that remained from earlier fossicking for tin.3 The china stone and clay industry that was poised to supply Australia’s potteries with almost all their requisite materials and to stimulate ceramic production commonwealth-wide arose, therefore, from incidental mining in the one area.4 About 1900, a granite dyke sixteen kilometres south-east of Penneshaw was pegged out for the mining of allegedly promising tin deposits. -

The Basset Family: Marriage Connections and Socio-Political Networks

THE BASSET FAMILY: MARRIAGE CONNECTIONS AND SOCIO-POLITICAL NETWORKS IN MEDIEVAL STAFFORDSHIRE AND BEYOND A THESIS IN History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS By RACHAEL HAZELL B. A. Drury University, 2011 Kansas City, Missouri THE BASSET FAMILY: MARRIAGE CONNECTIONS AND SOCIO-POLITICAL NETWORKS IN MEDIEVAL STAFFORDSHIRE AND BEYOND Rachael Hazell, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri- Kansas City, 2015 ABSTRACT The political turmoil of the eleventh to fourteenth centuries in England had far reaching consequences for nearly everyone. Noble families especially had the added pressure of ensuring wise political alliances While maintaining and acquiring land and wealth. Although this pressure would have been felt throughout England, the political and economic success of the county of Staffordshire, home to the Basset family, hinged on its political structure, as Well as its geographical placement. Although it Was not as subject to Welsh invasions as neighboring Shropshire, such invasions had indirect destabilizing effects on the county. PoWerful baronial families of the time sought to gain land and favor through strategic alliances. Marriage frequently played a role in helping connect families, even across borders, and this Was the case for people of all social levels. As the leadership of England fluctuated, revolts and rebellions called poWerful families to dedicate their allegiances either to the king or to the rebellion. Either way, during the central and late Middle Ages, the West Midlands was an area of unrest. Between geography, weather, invaders from abroad, and internal political debate, the unrest in Staffordshire Would create an environment Where location, iii alliances, and family netWorks could make or break a family’s successes or failures.