Breaking the Ice: Inquiry Into 'Ice' Use in the Northern Territory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Ibangs Meeting: the 20Th Annual Genes, Brain & Behavior Meeting

5/25/2018 Program for Thursday, May 17th 2018 IBANGS MEETING: THE 20TH ANNUAL GENES, BRAIN & BEHAVIOR MEETING WELCOME PROGRAM INDEXES PROGRAM FOR THURSDAY, MAY 17TH Days: next day all days View: session overview talk overview 08:30-16:00 Session FV: Pre-IBANGS Satellite Meeting, Functional Validation for Neurogenetics Location: Phillips Hall in the Siebens building room 1-11. The Siebens building is located at the Downtown Mayo Clinic Campus (not the Mayo Civic Center). Description:The transformative nature of next generation sequencing has changed how neuroscientists approach genomic sequence variation. Highly multiplexed molecular testing is providing an expanded level of information from which to make informed phenotypic predictions. The importance of this is reflected in the unprecedented expansion of genomic testing to determine the basis of neurologic conditions. Genomic testing results in many instances provide a definitive basis of a neurologic condition. However, in almost a high proportion of cases, the genomic sequencing results are confounded by the ambiguity of variants with uncertain clinical significance. Herein lies the key with which institutions will lead in the area of genomic medicine. There exists a critical need to provide a mechanism by which uncertain findings can be functionally characterized and translated into clinically actionable results. It is within thisr ealm that academic societies such as IBANGS can have a substantial and informative role on the future of clinical research and practice. This symposium will introduce the challenges and opportunities that exist in the field of human clinical neurogenetics and follow this with presentations of active work in the field of functional genetic finding validation for neurogenetics with a look to the future of genomic neurogenetics. -

CPDD 77Th Annual Meeting • Arizona Biltmore, Phoenix, Arizona

CPDD 77th Annual Meeting • Arizona Biltmore, Phoenix, Arizona 1 2 EFFECT OF HEMISPHERIC DOMINANT VERSUS NON- SEX, DRUGS, AND VIOLENCE: AN ANALYSIS OF WOMEN IN DOMINANT INSULAR DAMAGE ON SMOKING BEHAVIORS. DRUG COURT. Amir Abdolahi1,2, Geoffrey Williams2, Curtis Benesch2, Henry Wang2, Eric Abenaa Acheampong2, Catherine W Striley3, David O Fakunle1, Linda Cottler3; Spitzer3, Bryan Scott3, Robert Block2, Edwin van Wijngaarden2; 1Philips 1Mental Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Research, Briarcliff Manor, NY, 2University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, MD, 2University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, 3Epidemiology, University of 3Rochester General Health System, Rochester, NY Florida, Gainesville, FL Aims: Recent evidence suggests that damage to the insular cortex (IC), the cere- Aims: This analysis examines exposure to violence and substance use disorders bral cortex beneath the sylvian fissure, disrupts nicotine-induced cravings and is among women in drug court who are: current sex traders (CST), former sex associated with a greater likelihood of cessation relative to non-IC damage. The traders (FST), or women who have never traded sex. role hemispheric dominance may play in regulating these changes, however, has Methods: Data comes from 319 women recruited from a Municipal Drug Court not yet been explored. We hypothesized that current smokers with damage to System in the Midwest. Women were interviewed about sex trading, violence, their dominant IC would experience less withdrawal and cravings and be more and drug use. Women who traded sex in the past 4 months for drugs, alcohol, likely to quit than those with non-dominant IC damage. or other resources were classified as CST, while women who previously traded Methods: A total of 37 smokers with unilateral IC strokes (17 dominant and 20 sex but not in the past 4 months were classified as FST. -

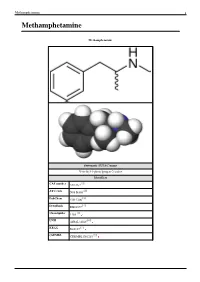

Methamphetamine 1 Methamphetamine

Methamphetamine 1 Methamphetamine Methamphetamine Systematic (IUPAC) name N-methyl-1-phenylpropan-2-amine Identifiers [1] CAS number 537-46-2 [2] ATC code N06 BA03 [3] PubChem CID 1206 [4] DrugBank DB01577 [5] ChemSpider 1169 [6] UNII 44RAL3456C [7] KEGG D08187 [8] ChEMBL CHEMBL1201201 Methamphetamine 2 Synonyms Desoxyephedrine Pervitin Anadrex Methedrine Methylamphetamine Syndrox Desoxyn Chemical data Formula C H N 10 15 Mol. mass 149.233 g/mol [9] [10] SMILES eMolecules & PubChem Pharmacokinetic data Bioavailability 62.7% oral; 79% nasal; 90.3% smoked; 99% rectally; 100% IV Metabolism Hepatic [11] Half-life 9–12 hours Excretion Renal Therapeutic considerations Pregnancy cat. C(US) Legal status Controlled (S8) (AU) Schedule I (CA) Schedule II (US) Class A(NZ) Schedule 5(SA) Injectable:Class A, Oral: A(UK) Routes Medical: Oral Recreational: Oral, I.V., I.M., Insufflation, Inhalation, Rectal [12] (what is this?) (verify) [13] Methamphetamine (pronounced /ˌmɛθæmˈfɛtəmiːn/ listen ), also known as metamfetamine (INN for the (+) form), methylamphetamine, N-methylamphetamine, desoxyephedrine, and colloquially as "meth" or "crystal meth", is a psychostimulant of the phenethylamine and amphetamine class of drugs. It increases alertness, concentration, energy, and in high doses, can induce euphoria, enhance self-esteem, and increase libido.[14] [15] Methamphetamine has high potential for abuse and addiction by activating the psychological reward system via triggering a cascading release of dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin in the brain. Methamphetamine is FDA approved for the treatment of ADHD and exogenous obesity, marketed in the USA under the trademark name Desoxyn.[16] Methamphetamine is illicitly synthesized and then sold in a crystalline form resembling small shards of odorless, bitter-tasting crystals; leading to the colloquial nickname "crystal meth". -

Monday Scientific Session Listing:261–437

MONDAY SCIENTIFIC SESSION LISTING:261–437 Washington, DC Nov. 11–15 Complete Session Listing Monday AM LECTURE Walter E. Washington Convention Center SYMPOSIUM Walter E. Washington Convention Center 261. Neural Circuits Controlling the Selection and 263. ● Assembly and Maintenance of the Peripheral Nerve Persistence of Sensory Information — CME Node of Ranvier in Development, Health, and Disease — CME Mon. 8:30 AM - 9:40 AM — Hall D Speaker: T. MOORE, Stanford Univ. and Howard Hughes Mon. 8:30 AM - 11:00 AM — 146A Med. Inst. Chair: H. J. WILLISON The processing and retention of sensory input is influenced Co-Chair: P. J. BROPHY by a number of endogenous factors, such as arousal, Nodes of Ranvier are the sites of saltatory conduction, motivation, and cognitive control. These factors appear to a fundamental adaption of myelinated axons. Our constrain the sensory information guiding adaptive behavior. understanding of the molecular organization of the nodal AM Mon. This lecture will discuss recent evidence on the neural region has rapidly advanced. Many components have been circuits involved in the modulation, filtering, and persistence identified, as have the interactions among the axonal and of sensory information and their relation to basic cognitive glial molecules, accounting for the specialized features of functions such as attention and working memory. The lecture nodal, paranodal, and juxtaparanodal domains. Human will include evidence from a range of model systems and autoimmune neuropathies are diseases that target glial approaches, as well as a discussion on the relevance to and axonal nodal proteins and glycolipids, leading to mental disorders. nodal disruption and conduction block. -

Risky Subjectivity

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Risky Subjectivity: The Effects of Cultural Discourses of Addiction on Methamphetamine Using HIV+ Men Who Have Sex with Men in San Diego A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Theodore Karwoski Gideonse Committee in charge: Professor Janis H. Jenkins, Chair Professor Suzanne Brenner Professor Norman Bryson Professor Steven Parish Professor Thomas Patterson Professor Nancy G. Postero 2013 Signature Page The Dissertation of Theodore Karwoski Gideonse is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2013 iii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the man who in the text I call Sam. iv Table of Contents Signature Page .......................................................................................................................... iii Dedication .................................................................................................................................. iv Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... v List of Figures .......................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................. viii Vita .............................................................................................................................................. -

Methamphetamine: Fact Vs

METHAMPHETAMINE: FACT VS. FICTION AND LESSONS FROM THE CRACK HYSTERIA Carl L. Hart, Joanne Csete, Don Habibi Department of Psychology, Columbia University, Division on Substance Abuse, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, Institute for Research in African-American Studies, Columbia University, Open Society Foundation and Department of Philosophy, University of North Carolina Wilmington Address Correspondence to: Carl L. Hart, Ph.D. New York State Psychiatric Institute 1051 Riverside Dr., Unit 120 New York, NY 10032, U.S.A. Voice (212) 543-5884 FAX (212) 543-5991 [email protected] Hart: Methamphetamine dangers, 1 Executive Summary The purpose of this report is to provide a critical examination of the available evidence on illicit methamphetamine use and its consequences in the United States and internationally. It is the aim of this report to dispel some of the myths about the effects of methamphetamine and other illicit drugs using the best available scientific data. Further, it is our hope that this analysis will lead to more rational policies for dealing with both legal and illegal amphetamine. The report begins with an examination of the lessons learned from the “crack cocaine scare” in the 1980s. In this way, the reader can draw parallels between society’s response to crack cocaine then, and methamphetamine now. The report then describes distinctions and similarities between methamphetamine and other amphetamine-type stimulants. Also examined is the prevalence of methamphetamine use and public policies in response to the perceived increased use of the drug and perceived drug-related problems. -

September, 2009

NIDA - Director's Report - September, 2009 NIDA Home > Publications > Director's Reports Director's Report to the National Advisory Council on Drug Abuse - September, 2009 Index Research Findings Multi-Division Research Basic Neurosciences Research Basic Behavioral Research Behavioral and Brain Development Research Clinical Neuroscience Research Epidemiology and Etiology Research Prevention Research Research on Behavioral and Combined Treatments for Drug Abuse Research on Pharmacotherapies for Drug Abuse Research on Medical Consequences of Drug Abuse and Co-Occurring Infections (HIV/AIDS, HCV) Services Research Clinical Trials Network Research International Research Intramural Research Program Activities Extramural Policy and Review Activities Congressional Affairs International Activities Meetings and Conferences Media and Education Activities Planned Meetings Publications Staff Highlights Grantee Honors https://archives.drugabuse.gov/DirReports/DirRep909/Default.html[11/17/16, 11:20:48 PM] NIDA - Director's Report - September, 2009 Archive Home | Accessibility | Privacy | FOIA (NIH) | Current NIDA Home Page The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) , a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Questions? _ See our Contact Information. https://archives.drugabuse.gov/DirReports/DirRep909/Default.html[11/17/16, 11:20:48 PM] NIDA - Director's Report - September, 2009 NIDA Home > Publications > Director's Reports > September, 2009 Index Director's Report to the National Advisory Council on Drug Abuse - September, 2009 Index Research Findings - Basic Neuroscience Research Research Findings Toll-Like Receptor-3 Activation in Human Neuronal Cells Induces Basic Neurosciences Interferon-λ Expression Research Basic Behavioral Research Interferon lambda (IFN-λ) belongs to the type III family of IFNs which when activated exerts antiviral, antitumor and immunoregulatory activities. -

Meeting Program

JOINTLYJOINTLLYY S SPONSORED P O N S R E DO STATEMENTS A TE ETNMT Accreditation Statement:St t aS eet mt :n This activity has been planned pneebs l and implemented pmidnadenna l mnee nted in accordance withwith the Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Accreditatation Council forffoor Continuing Medical EducatiEducationtion (ACCME) throuthroughgghh the joint jooint sponsorship of Temple University School Scho of Medicine and The College leoCdhTneaniicdMfeoloo egel g ooe n Problems of Drug Dru Dependence. D e p e n d e n c e TempleT. University School of Medicine M is accredited by the ACCME to sposponsoronsor Continuing Medical EduEducationucation ffoforo physicians.na.sicisyhrp Certification e Crit ffiication Statement:St t aS eet mt :n Temple UniversityesrviUnelmpeT sity School of Medicine designates designnates this live activity forffoo aar maximmumu2 m of 22 AMAAMAMAMA PPRARARA CCaCategoryattegegoryry 1 Credit(s)™.CCrrrededdiiitt((s)s) .™ PPhysiciansa h s i c i ny s shouldsh ould claimim only the credit commensuratec withwwiith the extent extennt of their participation in the a.activitytyivtic . Disclosure i srolcDs Policy:uPelo l :yci It is the policy of o the Temple University School Schoool of Medicine, The Albert J.J.J Finestone,FDinestone, M.D,.M O, Officefffffiice of Continuing Medical Mediccal Education that the speaker r and provider disclosedrsiedivodrnpa sclose real or apparent conconflictsflfl ci cts of interest relating to the topics of this educational edducational activity, activity and also disclose di i cs discussions idesol ssucs ofsfonoi unlabunlabeled/unapprovedeled/unapproved ap uses oof o drdrugs g sf orru devices during their presentation(s). -

Welcome to the 41St Annual Meeting of the Winter Conference on Brain Research

Welcome to the 41st annual meeting of the Winter Conference on Brain Research I extend a special welcome to all of you who are new to the meeting. I believe that you will find this to be one of the most diverse, high-quality, and content-heavy meetings in neuroscience that many of you will attend. Besides having the chance to hear neuroscientists from around the world present their work at formal sessions, this meeting offers the unique opportunity to socialize and ski with these same scientists in an informal setting. Those of you who are WCBR habitués know that the success of the meeting depends upon your individual contributions to each session, even if you are not a panel or workshop speaker or a poster presenter. Our biggest strength is the scientific interaction that occurs at these formal sessions, as well as the personal interactions that take place after the sessions have ended. For this reason, I urge you to welcome newcomers (blue badges) and Travel Fellows (badges with purple dots) into your discussions, and social and ski groups as often as possible to make sure that this will be the first of their many future WCBR meetings. The week begins on Saturday night with the opening reception. The opening breakfast on Sunday will feature our keynote speaker, Dr. Samuel Weiss. A previous WCBR attendee known to many of you, Sam is also a Professor in the Department of Cell Biology & Anatomy/Phar- macology & Therapeutics, and a member of the Genes and Development Research Group Faculty of Medicine, University of Calgary. -

The Historical and Current Perspectives of the Methamphetamine Abuse Phenomena in the United States

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Avary Justice Kolasinski for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Mathematics presented on May 28, 2013. The Historical and Current Perspectives of the Methamphetamine Abuse Phenomena in the United States. Abstract approved: Ray Tricker Methamphetamine has flooded the media for the past two decades however, this drug has impacted the nation for many decades prior. Since its synthesis in 1893, methamphetamine has appealed to various aspects of society including soldiers, housewives, college students, businessmen, truck drivers, drugged crazed hippies, and athletes. The extensive effects, easy production methods, and low-cost has caused methamphetamine to maintain an influence in the US for almost a century. However, the reality of methamphetamine use is unknown to the majority of today’s society. The media has profiled users, exaggerated use, and amplified the effects through prevention programs such as the Oregonian’s Faces of Meth and the Montana Meth Project. This has caused a current, ignorant perspective of methamphetamine use. The actuality of the matter is that methamphetamine remains to be one of the least used drugs in America but is being defined by the socially stigmatized term “epidemic”. The false portrayal of methamphetamine by the media is in hopes to prevent further use. Nevertheless, is it moral for the media to exaggerate drug use for the good of society? Methamphetamine is not a drug to be reckoned with but, it is also not the sloughing beast that has been displayed in the media. -

Narratives of Starting, Using, and Stopping Methamphetamine Use

NARRATIVES OF STARTING, USING, AND STOPPING METHAMPHETAMINE USE BY JOHN DANCE A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington (2018) 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................... 5 Abstract ......................................................................................................................................... 6 Chapter one: thesis introduction and overview ........................................................................... 7 Methamphetamine use in New Zealand ....................................................................................... 8 Thesis structure ........................................................................................................................... 18 Chapter two: methamphetamine, drug panics and authoritative understandings of drug users ..................................................................................................................................................... 23 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 23 Methamphetamine and ‘drug panics’ ......................................................................................... 25 The individualisation of drug use in authoritative discourses ................................................... -

The Economic Cost of Methamphetamine Use in the United States, 2005

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NATIONAL SECURITY The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Drug Policy Research Center View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND mono- graphs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors.