Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian Art 1

RUSSIAN ART 1 RUSSIAN ART Christie’s dominated the global market for Russian Works of Art and Fabergé in 2016, with our Russian Art sales achieving more than £12 million internationally. For the tenth consecutive season, our Russian Art auctions saw the highest sell-through rates in the market. With a focus on outstanding quality, Christie’s continues to attract both emerging and established collectors in the field. For over a decade, Christie’s has set world auction records in every Russian Art sale. We have broken a total of six records in the past two years, including two in excess of £4 million. Christie’s has set world records for over 50 of Russia’s foremost artists, including Goncharova, Repin, Levitan, Vereshchagin, Vasnetsov, Borovikovsky, Serov, Somov, Lentulov, Mashkov, Annenkov and Tchelitchew. Six of the 10 most valuable paintings ever purchased in a Russian Art sale were sold at Christie’s. Christie’s remains the global market leader in the field of Russian Works of Art and Fabergé, consistently achieving the highest percentage sold by both value and lot for Russian Works of Art. Christie’s closes 2016 with a 60% share of the global Fabergé market, and a 62% share of the global market for Russian Works of Art. cover PROPERTY FROM AN IMPORTANT EUROPEAN COLLECTION KONSTANTIN KOROVIN (1861–1939) Woodland brook, 1921 Estimate: £120,000–150,000 Sold for: £317,000 London, King Street · November 2016 back cover PROPERTY OF A MIDDLE EASTERN COLLECTOR A GEM-SET PARCEL-GILT SILVER-MOUNTED CERAMIC TOBACCO HUMIDOR The mounts marked K. -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

Qt0m64w57q.Pdf

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Ideologies of Pure Abstraction Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0m64w57q Author Kim, Amy Chun Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Ideologies of Pure Abstraction By Amy Chun Kim A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Whitney Davis, Chair Professor Todd Olson Professor Robert Kaufman Spring 2015 Ideologies of Pure Abstraction © 2015 Amy Chun Kim Abstract Ideologies of Pure Abstraction by Amy Chun Kim Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art University of California, Berkeley Professor Whitney Davis, Chair This dissertation presents a history of the development of abstract art in the 1920s and 1930s, the period of its expansion and consolidation as an identifiable movement and practice of art. I argue that the emergence of the category of abstract art in the 1920s is grounded in a voluntaristic impulse to remake the world. I argue that the consolidation of abstract art as a movement emerged out of the Parisian reception of a new Soviet art practice that contained a political impetus that was subsequently obscured as this moment passed. The occultation of this historical context laid the groundwork for the postwar “multiplication” of the meanings of abstraction, and the later tendency to associate its early programmatic aspirations with a more apolitical mysticism. Abstraction has a long and varied history as both a conceptual-aesthetic practice and as an ideal. -

Russian Art at Christie's in June

For Immediate Release 21 May 2008 Contact: Alex Kindermann 020 7389 2289 [email protected] Matthew Paton 020 7389 2965 [email protected] RUSSIAN ART AT CHRISTIE’S IN JUNE • DEDICATED RUSSIAN ART SALE TO OFFER WORKS BY GONCHOROVA, LARIONOV AND KONCHALOVSKI • ELSEWHERE AT CHRISTIE’S IN JUNE, A GONCHAROVA MASTERPIECE EXPECTED TO REALISE UP TO £4.5 MILLION, AND THE ONASSIS FABERGÉ BUDDHA LEADS THE AUCTION OF JEWELRY London – In June 2008, Christie’s will offer a wide array of exceptional Russian works of art, offered at the auctions of Russian Art, Icons and Artefacts from the Orthodox World, The London Jewels Sale, and the Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale, all taking place at King Street. Highlights include: Icons and Artefacts from the Orthodox World Monday 9 June 2008 Building on the strength of 2007, when auctions of Icons at Christie’s realized over £7 million, an increase of 724% on 2006 (total: £971,000), the auction on 9 June will offer 230 lots spanning the 15th to the 20th century. The most valuable auction of Icons ever organised in the international marketplace, the sale is expected to fetch in the region of £5 million. The auction will include significant Russian and Greek icons as well as valuable Orthodox artefacts such as a Book of Gospels, once belonging to the Grand Duke Aleksander Mikhailovich Romanov, son-in-law of Tsar Alexander III (estimate: £35,000-45,000) illustrated left. The Adoration of the Mother of God by Patron Saints of the Stroganov Family is a superb example of 17th century icon painting (lot 28, estimate: £40,000-60,000) illustrated right. -

Kazimir Malevich Was a Russian Artist of Ukrainian Birth, Whose Career Coincided with the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and Its Social and Cultural Aftermath

QUICK VIEW: Synopsis Kazimir Malevich was a Russian artist of Ukrainian birth, whose career coincided with the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and its social and cultural aftermath. Malevich was the founder of the artistic and philosophical school of Suprematism, and his ideas about forms and meaning in art would eventually form the theoretical underpinnings of non- objective, or abstract, art making. Malevich worked in a variety of styles, but his most important and famous works concentrated on the exploration of pure geometric forms (squares, triangles, and circles) and their relationships to each other and within the pictorial space. Because of his contacts in the West, Malevich was able to transmit his ideas about painting to his fellow artists in Europe and the U.S., thus profoundly influencing the evolution of non-representational art in both the Eastern and Western traditions. Key Ideas • Malevich worked in a variety of styles, from Impressionism to Cubo-Futurism, arriving eventually at Suprematism - his own unique philosophy of painting and art perception. • Malevich was a prolific writer. His treatises on philosophy of art address a broad spectrum of theoretical problems and laid the conceptual basis for non-objective art both in Europe and the United States. • Malevich conceived of an independent comprehensive abstract art practice before its definitive emergence in the United States. His stress on the independence of geometric form influenced many generations of abstract artists in the West, especially Ad Reinhardt. © The Art Story Foundation – All rights Reserved For more movements, artists and ideas on Modern Art visit www.TheArtStory.org DETAILED VIEW: Childhood Malevich was born in Ukraine to parents of Polish origin, who moved continuously within the Russian Empire in search of work. -

Arts and Crafts in Late Imperial Russia: Reviving the Kustar Art Industries Wendy Salmond Chapman University, [email protected]

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Art Faculty Books and Book Chapters Art 1996 Arts and Crafts in Late Imperial Russia: Reviving the Kustar Art Industries Wendy Salmond Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/art_books Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Salmond, Wendy R. Arts and Crafts ni Late Imperial Russia: Reviving the Kustar Art Industries, 1870-1917. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Faculty Books and Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The librumtsevo Workshops In the academic debate over who will emerge the victor in the battle between factory and kustar industry, artistic kustar production occu pies one of the strongest positions, for the simple fact that artistic activity doesn't need heavy machinery, large engines, and the exten sive appliances of the factory. N. Elfimov N THE COMPLEX STRUCTURE ofRussian peasant society at the close of the nineteenth century, the kustar, or peasant handicraftsman, occupied an uncertain and ambivalent posi tion. Public opinion swung between two extremes. Was he the heir to centuries of folk culture or simply a primitive form of proto industrialization? Was he Russia's only hope for the future or a source of national shame? Was he a precious symbol of country life or a symptom of agriculture's decline?1 The officially sanctioned definition of kustar industry as "the small-scale family organization of produc tion of goods for sale, common among the peasant population ofRus sia as a supplement to agriculture" did little to answer these questions. -

Following the Black Square: the Cosmic, the Nostalgic & the Transformative in Russian Avant-Garde Museology Teofila Cruz-Uri

Following The Black Square: The Cosmic, The Nostalgic & The Transformative In Russian Avant-Garde Museology Teofila Cruz-Uribe A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Studies: Russia, East Europe and Central Asia University of Washington 2017 Committee: Glennys Young James West José Alaniz Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Jackson School of International Studies Cruz-Uribe ©Copyright 2017 Teofila Cruz-Uribe 1 Cruz-Uribe University of Washington Abstract Following The Black Square: The Cosmic, The Nostalgic & The Transformative In Russian Avant-Garde Museology Teofila Cruz-Uribe Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Jon Bridgman Endowed Professor Glennys Young History Department & Jackson School of International Studies Contemporary Russian art and museology is experiencing a revival of interest in the pioneering museology of the Russian artistic and political avant-garde of the early 20th century. This revival is exemplified in the work of contemporary Russian conceptual artist and self-styled ‘avant-garde museologist’ Arseniy Zhilyaev (b. 1984). Influential early 20th century Russian avant-garde artist and museologist Kazimir Malevich acts as the ‘tether’ binding the museologies of the past and present together, his famous “Black Square” a recurring visual and metaphoric indicator of the inspiration that contemporary Russian avant-garde museology and art is taking from its predecessors. This thesis analyzes Zhilyaev’s artistic and museological philosophy and work and determines how and where they are informed by Bolshevik-era avant-garde museology. This thesis also asks why such inspirations and influences are being felt and harnessed at this particular juncture in post-Soviet culture. -

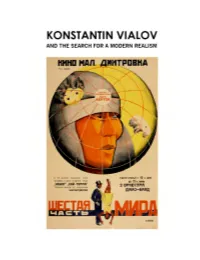

Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph

Aleksandr Deineka, Portrait of the artist K.A. Vialov, 1942. Oil on canvas. National Museum “Kyiv Art Gallery,” Kyiv, Ukraine Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. D. Edited by Brian Droitcour Design and production by Jolie Simpson Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Research Assistant: Elena Emelyanova, Research Curator, Rare Books Department, Russian State Library, Moscow Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2018 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2018 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Poster for Dziga Vertov’s Film Shestaia chast’ mira (A Sixth Part of the World), 1926. Lithograph, 42 1/2 x 28 1/4” (107.9 x 71.7 cm) Plate XVII Note on transliteration: For this catalogue we have generally adopted the system of transliteration employed by the Library of Congress. However, for the names of artists, we have combined two methods. For their names according to the Library of Congress system even when more conventional English versions exist: e.g. , Aleksandr Rodchenko, not Alexander Rodchenko; Aleksandr Deineka, not Alexander Deineka; Vasilii Kandinsky, not Wassily Kandinsky. Surnames with an “-ii” ending are rendered with an ending of “-y.” But in the case of artists who emigrated to the West, we have used the spelling that the artist adopted or that has gained common usage. Soft signs are not used in artists’ names but are retained elsewhere. TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 - ‘A Glimpse of Tomorrow’: Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. -

Shapiro Auctions

Shapiro Auctions RUSSIAN AND INTERNATIONAL FINE ART & ANTIQUES Saturday - October 25, 2014 RUSSIAN AND INTERNATIONAL FINE ART & ANTIQUES 1: A RUSSIAN ICON OF HOLY MARTYR PARASKEVA WITH LIFE USD 30,000 - 40,000 A RUSSIAN ICON OF HOLY MARTYR PARASKEVA WITH LIFE SCENES, NORTHERN SCHOOL, LATE 16TH-EARLY 17TH CENTURY, the figure of Saint Paraskeva, venerated as the healer of the blind as well as the patron saint of trade and commerce, stands in a field of flowering plants, she holds her martyr`s cross in one hand and an open scroll in the other, a pair of angels places a crown upon her head, surrounding the central image are fourteen scenes from the saint`s life, including the many tortures she endured under Emperor Antoninus Pius and the Roman governor Tarasius. Egg tempera, gold leaf and gesso on wood panel with kovcheg. Two insert splints on the back, one missing, one-half of the other present. 103 x 80 cm (40 ½ x 31 1/2 in.)PROVENANCESotheby`s, New York, June 10-11, 1981, lot 541.Collection of Bernard Winters, Armonk, New York (acquired at the above auction)Bernard J. Winters was a philanthropist and art collector who was captivated by Russian icons. Over a fifty-year period, he worked closely with Sotheby`s, Christie`s, and private collectors to cultivate his collection. His monumental icons, as well as those purchased from Natalie Hays Hammond, daughter of John Hays Hammond, diplomat, were some of his favored items. 2: A RUSSIAN ICON OF THE VENERABLE SERGIUS OF RADONEZH, USD 10,000 - 15,000 A RUSSIAN ICON OF THE VENERABLE SERGIUS OF RADONEZH, YAROSLAVL SCHOOL, CIRCA 1600, the saint depicted holding a scroll featuring an excerpt from his last words to his disciples, "Do not be sad Brothers, but rather preserve the purity of your bodies and souls, and love in a disinterested manner," above him is an image of the Holy Trinity - a reference to his Monastery of the Holy Trinity, as well as to the icon painted by Andrei Rublev under Sergius` successor, on a deep green background with a red border. -

Yakov Chernikhov Yakov Chernikhov

Yakov Chernikhov 1889-1951 The Soviet Piranesi A Major Collection of 47 Works Yakov Chernikhov 1889-1951 JAMES BUTTERWICK Alon Zakaim RUSSIAN AND EUROPEAN FINE ARTS Fine Art 34 Ravenscourt Rd. London W6 0UG 5-7 Dover St. London W1S 4LD +44 (0)20 8748 7320 +44 (0)20 7287 7750 [email protected] [email protected] www.jamesbutterwick.com www.alonzakaim.com 1 Front cover: from the series, Fundamentals of Modern Architecture (p. 48) Inside cover: detail, from the series, Pantheons of the Great Patriotic War (p. 32) Back inside cover: detail, from the series, Pantheons of the Great Patriotic War (p. 34) Current page: detail, from the series, Industrial Tales (p. 24) First published in London, 2018 by James Butterwick and Alon Zakaim Fine Art www.jamesbutterwick.com www.alonzakaim.com All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise, without first seeking the permission of the copyright owners and the publishers. All images in this catalogue are protected by copyright and should not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. © 2018 James Butterwick and Alon Zakaim Fine Art Design by Maggie Williams Printed by C3 Imaging Published on the occasion of Yakov Chernikhov 1889-1951: The Soviet Piranesi, a selling exhibition of works by James Butterwick and Alon Zakaim Fine Art at Alon Zakaim Fine Art, 5-7 Dover St. London W1S 4LD from Wednesday 5 December 2018 until Monday 21 January 2019 2 Contents -

Anthony Parton, Keys to the Enigmas of the World: Russian Icons in The

ANTHONY PARTON Keys to the Enigmas of the World: Russian Icons in the Theory and Practice of Mikhail Larionov, 1913 Dr Anthony Parton is Lecturer in the School of Education and Director of the Undergraduate Art History programme at Durham University. During the last 30 years he has researched and published on the life and art of the work of Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova. He is the author of Mikhail Larionov and the Russian Avant-Garde, 1998, and Goncharova, The Art and Design of Natalia Goncharova, 2010. 15 The “Foreword” to the catalogue of the Exhibition of Original Icon Paintings and Lubki written by Mikhail Larionov, and hence the introduction to the exhibition itself (1), which he also organised, is outrageously disorienting. It represents a typical example of Mikhail Larionov’s “bad-boy perversity” for which he deserved “to be spanked and put to bed rather than criticised”.1 As a foreword, the reader turns to it for clarification and guidance and yet receives none. In a passage reminiscent of the prophetic tone of Mme. Blavatsky, Larionov describes a “boor” who stumbles by accident into a period very different to his own.2 The familiar parameters by which he structures his sad and dismal existence are pulled apart since this period operates according to very different laws than those of his own. He is dazed, staggered, his tongue quivers in his parched throat and, forced back upon a conceptual paradigm that is critically flawed and unequal to the demands of the new reality that presents itself, he is forced to perish, shipwrecked in a vessel of his own making that he cannot escape – “to die like Narcissus”.3 As if this were not confusing enough for the reader of the s#ATALOGUEOF%XHIBITIONOF/RIGINAL)CON0AINTINGS catalogue / visitor to the exhibition, the narrative is suddenly and Lubki Moscow, 1913, Private Collection, England disrupted by a second and third passage, both claiming to be from “an unpublished history of art”.4 Here, matters become even more confusing. -

7. JD Books Futurist Period

Book Production of Russian Avant-Garde Books 1912-16 Johanna Drucker A simple question frames this paper: what can we learn by looking at the way Russian avant-garde books were made and thereby exposing some attitudes toward their production in their artist-author-producers? Many (though not all) were collaborative works among artists directly involved in the actual making of the books, and this distinguishes them from books whose production was contracted to printers by publishers. The Russian avant-garde artists are distinguished in this era by their involvement in production as well as a willingness to use a wide range of methods from rubber stamp and office equipment to hand coloring and collage. In his important study, The Look of Russian Literature, Gerald Janecek cites Donald Karshan, who states that in making their books, the Russian Futurist artists often used cheap, thin, brittle, wood pulp, “common paper, deliberately chosen, as an anti- establishment gesture and extension of ideological stance.”1 But what ideological stance? Choices about material properties and graphic codes of the earlier Futurist works inevitably link them to a later revolutionary political agenda and a larger historical narrative. And certainly the typography of LEF (1923) extends stylistic approaches developed among the Futurists—by way of Rodchenko, Lissitzky, and Mayakovsky. But what if we differentiate their style from attitudes toward their production? Looking at the specifics of making causes generalizations about the ideology of these artists difficult to sustain, or to contain in a historical narrative in which cultural radicalism and political activism necessarily align, since every instance is particular, not part of a simple, unified teleological agenda.