THE RUSSIAN AVANT-GARDE in the 1920S by Sarah Gates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Legacy Regained: Niko and the Russian Avant-Garde

A LEGACY REGAINED: NIKO AND THE RUSSIAN AVANT-GARDE PALACE EDITIONS Contents 8 Foreword Evgeniia Petrova 9 Preface Job de Ruiter 10 Acknowledgements and Notes to the Reader John E. Bowlt and Mark Konecny 13 Introduction John E. Bowlt and Mark Konecny Part I. Nikolai Khardzhiev and the Russian Avant Garde Remembering Nikolai Khardzhiev 21 Nikolai Khardzhiev RudolfDuganov 24 The Future is Now! lra Vrubel-Golubkina 36 Nikolai Khardzhiev and the Suprematists Nina Suetina 43 Nikolai Khardzhiev and the Maiakovsky Museum, Moscow Gennadii Aigi 50 My Memoir of Nikolai Khardzhiev Vyacheslav Ivanov 53 Nikolai Khardzhiev and My Family Zoya Ender-Masetti 57 My Meetings with Nikolai Khardzhiev Galina Demosfenova 59 Nikolai Khardzhiev, Knight of the Avant-garde Jean-C1aude Marcade 63 A Sole Encounter Szymon Bojko 65 The Guardian of the Temple Andrei Nakov 69 A Prophet in the Wilderness John E. Bowlt 71 The Great Commentator, or Notes About the Mole of History Vasilii Rakitin Writings by Nikolai Khardzhiev Essays 75 Autobiography 76 Poetry and Painting:The Early Maiakovsky 81 Cubo-Futurism 83 Maiakovsky as Partisan 92 Painting and Poetry Profiles ofArtists and Writers 99 Elena Guro 101 Boris Ender 103 In Memory of Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov 109 Vladimir Maiakovsky 122 Velimir Khlebnikov 131 Alexei Kruchenykh 135 VladimirTatlin 137 Alexander Rodchenko 139 EI Lissitzky Contents Texts Edited and Annotated by Nikolai Khardzhiev 147 Nikolai Khardzhiev Introductions to Kazimir Malevich's Autobiography (Parts 1 and 2) 157 Kazimir Malevieh Autobiography 172 Nikolai Khardzhiev Introduction to Mikhail Matiushin's The Russian Cubo-Futurists 173 Mikhail Matiushin The Russian Cubo-Futurists 183 Alexei Morgunov A Memoir 186 Nikolai Khardzhiev Introduction to Khlebnikov Is Everywhere! 187 Khlebnikov is Everywhere! Memoirs by Oavid Burliuk, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Amfian Reshetov, and on Osip Mandelshtam 190 Nikolai Khardzhiev Introduction to Lev Zhegin's Remembering Vasilii Chekrygin 192 Lev Zhegin Remembering Vasilii Chekrygin Part 11. -

Politics and History of 20Th Century Europe Shifted Radically, Swinging Like a Pendulum in a Dramatic Cause and Effect Relationship

Politics and history of 20th Century Europe shifted radically, swinging like a pendulum in a dramatic cause and effect relationship. I explored the correlation between art movements and revolutions, focusing specifically on Russian Constructivism and the Russian Revolution in the 1920s, as well as the Punk movement in East Germany that instigated the Fall of the Berlin Wall. I am fascinated by the structural similarities of these movements, and their shared desire of egalitarianism, which progressed with the support of opposing political ideologies. I chose fashion design because it was at the forefront of both Constructivism and Punk, and because it is what I hope to pursue as a career. After designing a full collection in 2D, I wanted to challenge myself by bringing one of my garments to life. The top is a plaster cast cut in half and shaped with epoxy and a lace up mechanism so that it can be worn. A paste made of plaster and paper pulp serves to attach the pieces of metal and create a rough texture that produces the illusion of a concrete wall. For the skirt, I created 11 spheres of various sizes by layering and stitching together different shades of white, cream, off-white, grey, and beige colored fabrics, with barbed wire and hardware cloth, that I then stuffed with Polyfil. The piece is wearable, and meant to constrict one’s freedom of movement - just like the German Democratic Party constricted freedom of speech in East Germany. The bottom portion is meant to suffocate the body in a different approach, with huge, outlandish, forms like the ones admired by the Constructivists. -

2. MAN with a MOVIE CAMERA: the First Cinema Screening Richard Bossons

1 2. MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA: the first cinema screening Richard Bossons 2 In the spring of 1927 Dziga Vertov [1] moved to Kyiv to work for VUFKU, the All-Ukrainian Photo Cinema Adminstration [2] after being sacked by Sovkino, the Russian equivalent, for being over budget on his film ‘One Sixth of the World’ [1926], and for refusing to present a script for ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ (which he had no intention of writing). Founded in 1922 VUFKU had a reputation for much more adventurous commissioning than Sovkino, and its predecessor Goskino, training, employing, and promoting mostly Ukrainian directors and cinematographers, and their films. VUFKU was effectively closed down in 1930, merged with Soyuzkino (Sovkino’s successor) after accusations of Nationalism, Formalism and other ‘unacceptable behaviour’ by the authorities in Moscow. In less than nine years the studios had produced over 140 full length feature films, and many documentaries, newsreels and animations. Films such as Oleksandr Dovzhenko’s ‘Ukrainian Trilogy’ (‘Zvenigora’ [1928], ‘Arsenal’ [1929], ‘Earth’ (‘Zemlya’) [1930]), and Dziga Vertov’s two masterpieces, ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ and ‘Enthusiasm: the Donbas Symphony’ [1930] earned VUFKU an international reputation. It controlled all aspects of the cinematic process including film-making, film processing, screening, publicity, and education. The main studios were originally in Odesa with others in Kharkiv and Yalta. After the earthquake in Yalta in 1927 VUFKU decided to relocate its equipment to large new studios in Kyiv in 1928. These are now the home of the Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Film Studio. The studio administration was also based in Kyiv at this time. -

Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2

MIT 4.602, Modern Art and Mass Culture (HASS-D) Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2 PHOTOGRAPHY, PROPAGANDA, MONTAGE: Soviet Avant-Garde “We are all primitives of the 20th century” – Ivan Kliun, 1916 UNOVIS members’ aims include the “study of the system of Suprematist projection and the designing of blueprints and plans in accordance with it; ruling off the earth’s expanse into squares, giving each energy cell its place in the overall scheme; organization and accommodation on the earth’s surface of all its intrinsic elements, charting those points and lines out of which the forms of Suprematism will ascend and slip into space.” — Ilya Chashnik , 1921 I. Making “Modern Man” A. Kasimir Malevich – Suprematism 1) Suprematism begins ca. 1913, influenced by Cubo-Futurism 2) Suprematism officially launched, 1915 – manifesto and exhibition titled “0.10 The Last Futurist Exhibition” in Petrograd. B. El (Elazar) Lissitzky 1) “Proun” as utopia 2) Types, and the new modern man C. Modern Woman? 1) Sonia Terk Delaunay in Paris a) “Orphism” or “organic Cubism” 1911 b) “Simultaneous” clothing, ceramics, textiles, cars 1913-20s 2) Natalia Goncharova, “Rayonism” 3) Lyubov Popova, Varvara Stepanova stage designs II. Monuments without Beards -- Vladimir Tatlin A. Constructivism (developed in parallel with Suprematism as sculptural variant) B. Productivism (the tweaking of “l’art pour l’art” to be more socialist) C. Monument to the Third International (Tatlin’s Tower), 1921 III. Collapse of the Avant-Garde? A. 1937 Paris Exposition, 1937 Entartete Kunst, 1939 Popular Front B. -

Russian Art 1

RUSSIAN ART 1 RUSSIAN ART Christie’s dominated the global market for Russian Works of Art and Fabergé in 2016, with our Russian Art sales achieving more than £12 million internationally. For the tenth consecutive season, our Russian Art auctions saw the highest sell-through rates in the market. With a focus on outstanding quality, Christie’s continues to attract both emerging and established collectors in the field. For over a decade, Christie’s has set world auction records in every Russian Art sale. We have broken a total of six records in the past two years, including two in excess of £4 million. Christie’s has set world records for over 50 of Russia’s foremost artists, including Goncharova, Repin, Levitan, Vereshchagin, Vasnetsov, Borovikovsky, Serov, Somov, Lentulov, Mashkov, Annenkov and Tchelitchew. Six of the 10 most valuable paintings ever purchased in a Russian Art sale were sold at Christie’s. Christie’s remains the global market leader in the field of Russian Works of Art and Fabergé, consistently achieving the highest percentage sold by both value and lot for Russian Works of Art. Christie’s closes 2016 with a 60% share of the global Fabergé market, and a 62% share of the global market for Russian Works of Art. cover PROPERTY FROM AN IMPORTANT EUROPEAN COLLECTION KONSTANTIN KOROVIN (1861–1939) Woodland brook, 1921 Estimate: £120,000–150,000 Sold for: £317,000 London, King Street · November 2016 back cover PROPERTY OF A MIDDLE EASTERN COLLECTOR A GEM-SET PARCEL-GILT SILVER-MOUNTED CERAMIC TOBACCO HUMIDOR The mounts marked K. -

The Russian Avant-Garde 1912-1930" Has Been Directedby Magdalenadabrowski, Curatorial Assistant in the Departmentof Drawings

Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art leV'' ST,?' T Chairm<ln ,he Boord;Ga,dner Cowles ViceChairman;David Rockefeller,Vice Chairman;Mrs. John D, Rockefeller3rd, President;Mrs. Bliss 'Ce!e,Slder";''i ITTT V P NealJ Farrel1Tfeasure Mrs. DouglasAuchincloss, Edward $''""'S-'ev C Burdl Tn ! u o J M ArmandP Bar,osGordonBunshaft Shi,| C. Burden,William A. M. Burden,Thomas S. Carroll,Frank T. Cary,Ivan Chermayeff, ai WniinT S S '* Gianlui Gabeltl,Paul Gottlieb, George Heard Hdmilton, Wal.aceK. Harrison, Mrs.Walter Hochschild,» Mrs. John R. Jakobson PhilipJohnson mM'S FrankY Larkin,Ronalds. Lauder,John L. Loeb,Ranald H. Macdanald,*Dondd B. Marron,Mrs. G. MaccullochMiller/ J. Irwin Miller/ S.I. Newhouse,Jr., RichardE Oldenburg,John ParkinsonIII, PeterG. Peterson,Gifford Phillips, Nelson A. Rockefeller* Mrs.Albrecht Saalfield, Mrs. Wolfgang Schoenborn/ MartinE. Segal,Mrs Bertram Smith,James Thrall Soby/ Mrs.Alfred R. Stern,Mrs. Donald B. Straus,Walter N um'dWard'9'* WhlTlWheeler/ Johni hTO Hay Whitney*u M M Warbur Mrs CliftonR. Wharton,Jr., Monroe * HonoraryTrustee Ex Officio 0'0'he "ri$°n' Ctty ot^New^or^ °' ' ^ °' "** H< J Goldin Comptrollerat the Copyright© 1978 by TheMuseum of ModernArt All rightsreserved ISBN0-87070-545-8 TheMuseum of ModernArt 11West 53 Street,New York, N.Y 10019 Printedin the UnitedStates of America Foreword Asa resultof the pioneeringinterest of its first Director,Alfred H. Barr,Jr., TheMuseum of ModernArt acquireda substantialand uniquecollection of paintings,sculpture, drawings,and printsthat illustratecrucial points in the Russianartistic evolution during the secondand third decadesof this century.These holdings have been considerably augmentedduring the pastfew years,most recently by TheLauder Foundation's gift of two watercolorsby VladimirTatlin, the only examplesof his work held in a public collectionin the West. -

Chapter 12. the Avant-Garde in the Late 20Th Century 1

Chapter 12. The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century 1 The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century: Modernism becomes Postmodernism A college student walks across campus in 1960. She has just left her room in the sorority house and is on her way to the art building. She is dressed for class, in carefully coordinated clothes that were all purchased from the same company: a crisp white shirt embroidered with her initials, a cardigan sweater in Kelly green wool, and a pleated skirt, also Kelly green, that reaches right to her knees. On her feet, she wears brown loafers and white socks. She carries a neatly packed bag, filled with freshly washed clothes: pants and a big work shirt for her painting class this morning; and shorts, a T-shirt and tennis shoes for her gym class later in the day. She’s walking rather rapidly, because she’s dying for a cigarette and knows that proper sorority girls don’t ever smoke unless they have a roof over their heads. She can’t wait to get into her painting class and light up. Following all the rules of the sorority is sometimes a drag, but it’s a lot better than living in the dormitory, where girls have ten o’clock curfews on weekdays and have to be in by midnight on weekends. (Of course, the guys don’t have curfews, but that’s just the way it is.) Anyway, it’s well known that most of the girls in her sorority marry well, and she can’t imagine anything she’d rather do after college. -

Staging Revolution: the Constructivist Debate About Composition

Staging Revolution: The Constructivist Debate about Composition Introduction Among the relatively few areas of agreement after the 1917 Russian Revolution, two are particularly noteworthy. The first is the widespread perception that the urban environment was chaotic. Whereas few people agreed as to the source of this chaos (choosing to blame it on the capitalists, the architects, or the intelligentsia), almost everyone believed that urban life after the revolution did not justify the sacrifices and traumas imposed by three years of civil war. The second area of agreement concerned the role of the theater: despite continued and almost irreconcilable differences about what the future should look like, there was almost complete agreement that art and theater could be “weapons” or tools in the revolution. Theater, in particular, would lead the way: from Lenin’s project for monumental propaganda (1918) to the Russian futurists’ declaration that the “streets should be a holiday of art for the people,” there was widespread agreement that art should be taken to the streets, that it was capable of communicating messages in a voice which would be understood, and that theatricality was the key to the unification of the arts. Ironically, one of the reasons why constructivism has been so difficult to study is the fact that it was long understood as a form of art which was against the creation of art. But one of the core values of constructivism was not the rejection of art but the belief that the only type of art which has meaning is one which challenges boundaries and definitions, and that part of this challenge concerns the relationship between the audience and the art work, whether we talk about theater, cinema, photography, or objects. -

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Johnson, Samuel. 2015. "The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463124 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 A dissertation presented by Samuel Johnson to The Department of History of Art and Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of Art and Architecture Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 Samuel Johnson All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Maria Gough Samuel Johnson “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 Abstract Although widely respected as an abstract painter, the Russian Jewish artist and architect El Lissitzky produced more works on paper than in any other medium during his twenty year career. Both a highly competent lithographer and a pioneer in the application of modernist principles to letterpress typography, Lissitzky advocated for works of art issued in “thousands of identical originals” even before the avant-garde embraced photography and film. -

David Quigley Learning to Live: Preliminary Notes for a Program Of

David Quigley In an essay published in 2009, Boris could play in a broader social context influenced the founding director John Groys makes the claim that “today art beyond the narrow realm of the art Andrew Rice, as well as the professors Learning to Live: education has no definite goal, no world. Josef Albers, Merce Cunningham, Robert Preliminary Notes method, no particular content that can Motherwell, John Cage, and the poets be taught, no tradition that can be Performing Pragmatism: Robert Creeley and Charles Olson. for a Program of Art transmitted to a new generation—which Art as Experience Unlike other trajectories of the critique Education for the is to say, it has too many.”69 While one On the first pages of Dewey’s Art as of the art object, the Deweyian tradition might agree with this diagnosis, one Experience from 1934, we read: did not deny the special status of art in 21st Century. immediately wonders how we should itself but rather resituated it within a Après John Dewey assess it. Are we to merely tacitly “By one of the ironic perversities that continuum of human experience. Dewey, acknowledge this situation or does this often attend the course of affairs, the as a thinker of egalitarianism and critique imply a call for change? Is this existence of the works of art upon which democracy, created a theory of art lack (or paradoxical overabundance) of the formation of an aesthetic theory based on the fundamental continuity goals, methods or content inherent to depends has become an obstruction of experience and practice, making the very essence of art education, or is to theory about them. -

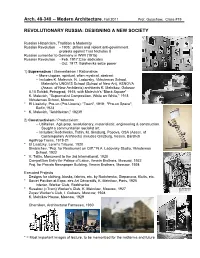

C:\Users\Kai\Documents\CMU Teaching\Modern\Handouts

Arch. 48-340 -- Modern Architecture, Fall 2011 Prof. Gutschow, Class #19 REVOLUTIONARY RUSSIA: DESIGNING A NEW SOCIETY Russian Historicism, Tradition & Modernity Russian Revolution - 1905: strikes and violent anti-government protests against Tsar Nicholas II Russian surrender to Germany in WWI (1915) Russian Revolution - Feb. 1917:Czar abdicates - Oct. 1917: Bolsheviks seize power 1) Suprematism / Elementarism / Rationalism -- More utopian, spiritual, often mystical, abstract -- Includes K. Malevich, N. Ladovsky, Vkhutemas School, Malevich's UNOVIS School (School of New Art), ASNOVA (Assoc. of New Architects) architects K. Melnikov, Golosov 0.10 Exhibit, Petrograd, 1915, with Malevich’s “Black Square” K. Malevich, "Suprematist Composition, White on White," 1918 Vkhutemas School, Moscow * El Lissitzky, Pro-un (Pro-Unovis): "Town", 1919; "Pro-un Space", Berlin,1923 * K. Malevich, "Arkhitekton," 1923ff 2) Constructivism / Productivism: -- Utilitarian, Agit-prop, revolutionary, materialistic, engineering & construction. Sought a communitarian socialist art. -- Includes: Rodchenko, Tatlin, M. Ginsburg, Popova, OSA (Assoc. of Contemporary Architects) includes Ginzburg, Vesnin, Barshch AgitProp Trains, 1919-21 * El Lissitzky, Lenin's Tribune, 1920 Simbirchev, “Proj. for Restaurant on Cliff," N.A. Ladovsky Studio, Vkhutemas School, 1922 * V. Tatlin, Monument to the 3rd International, 1920 Competition Entry for Palace of Labor, Vesnin Brothers, Moscow, 1922 Proj. for Pravda Newspaper Building, Vesnin Brothers, Moscow, 1924 Executed Projects Designs for clothing, kiosks, fabrics, etc. by Rodchenko, Stepanova, Klutis, etc. * Soviet Pavilion at Expo. des Art Décoratifs, K. Melnikov, Paris, 1925 Interior, Worker Club, Rodchenko * Rusakov (=Tram) Worker's Club, K. Melnikov, Moscow, 1927 Zuyev Worker's Club, I. Golosov, Moscow, 1928 K. Melnikov House, Moscow, 1929 Chernikov, Architectural Fantasies, 1930 * = Most important images of lecture, to be memorized for the midterms and future . -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town.