Anaphylaxis Guidelines November 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medicines to Avoid Before Allergy Skin Testing

Medicines to Avoid Before Allergy Skin Testing he American Academy of Otolaryngic Beta blockers are a risk factor for more serious and Allergy (AAOA) has developed this clinical treatment resistant anaphylaxis, making the use of beta care statement to assist healthcare providers blockers a relative contraindication to inhalant in determining which medicines patients skin testing. Tshould avoid prior to skin testing. These medicines are known to decrease or eliminate skin reactivity, causing a Treatment with omalizumab (anti-IgE antibody) can 20, 21 negative histamine control. Providers should have a suppress skin reactivity for up to six months. thorough understanding of the classes of medicines that Topical calcineurin inhibitors have a variable affect. could interfere with allergy testing. With proper patient Pimecrolimus22 did not affect histamine testing but counseling, the goal is to yield interpretable skin results tacrolimus12 did. without unnecessary medicine discontinuation. Herbal products have the potential to affect skin prick Antihistamines suppress the histamine response for testing. In the most comprehensive study,23 using a a variable period of time. In general, first-generation single–dose crossover study, it was felt that common antihistamines can be stopped for 72 hours, however, herbal products did not significantly affect the histamine several types including Cyproheptadine (Periactin) can skin response. However, complementary and other have active histamine suppression for up to 11 days. alternative medicines do sometimes have a significant Second-generation antihistamines also suppress testing histamine response24 and included butterbur, stinging for a variable length of time, up to 7 days. Astelin nettle, citrus unshiu powder, lycopus lucidus, spirulina, (Azelastine) nasal spray has been shown to suppress cellulose powder, traditional Chinese medicine, Indian 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 10 testing for up to 48 hours. -

FSI-D-16-00226R1 Title

Elsevier Editorial System(tm) for Forensic Science International Manuscript Draft Manuscript Number: FSI-D-16-00226R1 Title: An overview of Emerging and New Psychoactive Substances in the United Kingdom Article Type: Review Article Keywords: New Psychoactive Substances Psychostimulants Lefetamine Hallucinogens LSD Derivatives Benzodiazepines Corresponding Author: Prof. Simon Gibbons, Corresponding Author's Institution: UCL School of Pharmacy First Author: Simon Gibbons Order of Authors: Simon Gibbons; Shruti Beharry Abstract: The purpose of this review is to identify emerging or new psychoactive substances (NPS) by undertaking an online survey of the UK NPS market and to gather any data from online drug fora and published literature. Drugs from four main classes of NPS were identified: psychostimulants, dissociative anaesthetics, hallucinogens (phenylalkylamine-based and lysergamide-based materials) and finally benzodiazepines. For inclusion in the review the 'user reviews' on drugs fora were selected based on whether or not the particular NPS of interest was used alone or in combination. NPS that were use alone were considered. Each of the classes contained drugs that are modelled on existing illegal materials and are now covered by the UK New Psychoactive Substances Bill in 2016. Suggested Reviewers: Title Page (with authors and addresses) An overview of Emerging and New Psychoactive Substances in the United Kingdom Shruti Beharry and Simon Gibbons1 Research Department of Pharmaceutical and Biological Chemistry UCL School of Pharmacy -

Comparing the Effect of Venlafaxine and the Combination of Nortriptyline and Propranolol in the Prevention of Migraine

Comparing the Effect of Venlafaxine and the Combination of Nortriptyline and Propranolol in the Prevention of Migraine Arash Mosarrezaii1, Mohammad Reza Amiri Nikpour1, Ata Jabarzadeh2 1Department of Neurology, Imam Khomeini Hospital, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran, 2Medical Student, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran Abstract Background: Migraine is a debilitating neurological condition, which can be categorized into episodic and chronic groups based on its clinical pattern. Avoiding the risk factors exacerbating migraine is not enough to reduce the frequency and severity of migraine headaches, and in the case of non-receiving proper drug treatment, episodic migraines have the potential to become chronic, which increases the risk of cardiovascular complications RESEARCH ARTICLE and leaves great impact on the quality of life of patients and increasing the health-care costs. The objective of this research was to compare the effects of venlafaxine (VFL) and nortriptyline and propranolol in preventing migraines. Methods: This research is an interventional study performed on 60 patients with migraine admitted to the neurological clinic. Patients were visited at 3 time intervals. In each stage, the variables of headache frequency, headache severity, nausea, vomiting, and drowsiness were recorded. Data were analyzed using SPSS 23 software. Results: VFL drug with a daily dose of 37.5 mg is not only more tolerable in the long term but also leaves better effect in reducing the frequency and severity of headaches compared to the combination of nortriptyline and propranolol. Conclusion: VFL is an appropriate, effective, and tolerable alternative to migraine treatment. Key words: Migraine, nortriptyline, propranolol, venlafaxine INTRODUCTION Patients with CM are less likely to have full-time job than patients with episodic type, and they are at risk of job igraine is known as a common incapacity, anxiety, chronic pain, and depression 2 times neurological disorder and causes more than patients with episodic migraine. -

Octopamine and Tyramine Regulate the Activity of Reproductive Visceral Muscles in the Adult Female Blood-Feeding Bug, Rhodnius Prolixus Sam Hana* and Angela B

© 2017. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2017) 220, 1830-1836 doi:10.1242/jeb.156307 RESEARCH ARTICLE Octopamine and tyramine regulate the activity of reproductive visceral muscles in the adult female blood-feeding bug, Rhodnius prolixus Sam Hana* and Angela B. Lange ABSTRACT Monastirioti et al., 1996). Octopamine and tyramine signal via The role of octopamine and tyramine in regulating spontaneous G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), leading to changes in second contractions of reproductive tissues was examined in the messenger levels. The recently updated receptor classification α β female Rhodnius prolixus. Octopamine decreased the amplitude of (Farooqui, 2012) divides the receptors into Oct -R, Oct -Rs β β β spontaneous contractions of the oviducts and reduced RhoprFIRFa- (Oct 1-R, Oct 2-R, Oct 3-R), TYR1-R and TYR2-R. In general, β α induced contractions in a dose-dependent manner, whereas tyramine Oct -Rs lead to elevation of cAMP while Oct -R and TYR-Rs lead to 2+ only reduced the RhoprFIRFa-induced contractions. Both octopamine an increase in Ca (Farooqui, 2012). and tyramine decreased the frequency of spontaneous bursal The movement of eggs in the reproductive system of contractions and completely abolished the contractions at Rhodnius prolixus starts at the ovaries, the site of egg maturation. 5×10−7 mol l−1 and above. Phentolamine, an octopamine receptor Upon ovulation, mature eggs are released into the oviducts antagonist, attenuated the inhibition induced by octopamine on the (Wigglesworth, 1942). Eggs are then guided, via oviductal oviducts and the bursa. Octopamine also increased the levels of peristaltic and phasic contractions, to the common oviduct, where cAMP in the oviducts, and this effect was blocked by phentolamine. -

Schizophrenia Care Guide

August 2015 CCHCS/DHCS Care Guide: Schizophrenia SUMMARY DECISION SUPPORT PATIENT EDUCATION/SELF MANAGEMENT GOALS ALERTS Minimize frequency and severity of psychotic episodes Suicidal ideation or gestures Encourage medication adherence Abnormal movements Manage medication side effects Delusions Monitor as clinically appropriate Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome Danger to self or others DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA/EVALUATION (PER DSM V) 1. Rule out delirium or other medical illnesses mimicking schizophrenia (see page 5), medications or drugs of abuse causing psychosis (see page 6), other mental illness causes of psychosis, e.g., Bipolar Mania or Depression, Major Depression, PTSD, borderline personality disorder (see page 4). Ideas in patients (even odd ideas) that we disagree with can be learned and are therefore not necessarily signs of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is a world-wide phenomenon that can occur in cultures with widely differing ideas. 2. Diagnosis is made based on the following: (Criteria A and B must be met) A. Two of the following symptoms/signs must be present over much of at least one month (unless treated), with a significant impact on social or occupational functioning, over at least a 6-month period of time: Delusions, Hallucinations, Disorganized Speech, Negative symptoms (social withdrawal, poverty of thought, etc.), severely disorganized or catatonic behavior. B. At least one of the symptoms/signs should be Delusions, Hallucinations, or Disorganized Speech. TREATMENT OPTIONS MEDICATIONS Informed consent for psychotropic -

![Selective Labeling of Serotonin Receptors Byd-[3H]Lysergic Acid](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9764/selective-labeling-of-serotonin-receptors-byd-3h-lysergic-acid-319764.webp)

Selective Labeling of Serotonin Receptors Byd-[3H]Lysergic Acid

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 75, No. 12, pp. 5783-5787, December 1978 Biochemistry Selective labeling of serotonin receptors by d-[3H]lysergic acid diethylamide in calf caudate (ergots/hallucinogens/tryptamines/norepinephrine/dopamine) PATRICIA M. WHITAKER AND PHILIP SEEMAN* Department of Pharmacology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada M5S 1A8 Communicated by Philip Siekevltz, August 18,1978 ABSTRACT Since it was known that d-lysergic acid di- The objective in this present study was to improve the se- ethylamide (LSD) affected catecholaminergic as well as sero- lectivity of [3H]LSD for serotonin receptors, concomitantly toninergic neurons, the objective in this study was to enhance using other drugs to block a-adrenergic and dopamine receptors the selectivity of [3HJISD binding to serotonin receptors in vitro by using crude homogenates of calf caudate. In the presence of (cf. refs. 36-38). We then compared the potencies of various a combination of 50 nM each of phentolamine (adde to pre- drugs on this selective [3H]LSD binding and compared these clude the binding of [3HJLSD to a-adrenoceptors), apmo ie, data to those for the high-affinity binding of [3H]serotonin and spiperone (added to preclude the binding of [3H[LSD to (39). dopamine receptors), it was found by Scatchard analysis that the total number of 3H sites went down to 300 fmol/mg, compared to 1100 fmol/mg in the absence of the catechol- METHODS amine-blocking drugs. The IC50 values (concentrations to inhibit Preparation of Membranes. Calf brains were obtained fresh binding by 50%) for various drugs were tested on the binding of [3HLSD in the presence of 50 nM each of apomorphine (A), from the Canada Packers Hunisett plant (Toronto). -

Can Hepatic Coma Be Caused by a Reduction of Brain Noradrenaline Or Dopamine?

Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.18.9.688 on 1 September 1977. Downloaded from Gut, 1977, 18, 688-691 Can hepatic coma be caused by a reduction of brain noradrenaline or dopamine? L. ZIEVE AND R. L. OLSEN From the Department ofMedicine, Minneapolis Veterans Hospital, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and Department of Chemistry, Hamline University, St. Paul, Minnesota, USA SUMMARY Intraventricular infusions of octopamine which raised brain octopamine concentrations more than 20 000-fold resulted in reductions in brain noradrenaline and dopamine by as much as 90% without affecting the alertness or activity of normal rats. As this reduction of brain catechol- amines is much greater than any reported in hepatic coma, we do not believe that values observed in experimental hepatic failure have aetiological significance for the encephalopathy that ensues. Though catecholaminergic nerve terminals represent dopamine and noradrenaline had no discernible only a small proportion of brain synapses (Snyder et effect on the state of alertness of the animals. al., 1973), the reduction in brain dopamine or nor- adrenaline by the accumulation of false neuro- Methods transmitterssuch as octopamine or of aromaticamino acids such as phenylalanine or tyrosine has been ANIMALS suggested as a cause of hepatic coma (Fischer and Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing between 300 and Baldessarini, 1971; Dodsworth et al., 1974; Fischer 350 were g prepared by the method of Peterson and http://gut.bmj.com/ and Baldessarini, 1975; Munro et al., 1975). The Sparber (1974) for intraventricular infusions of following data have been cited in support of this octopamine. Rats of 250-400 g were used as controls. -

Structure-Cytotoxicity Relationship Profile of 13 Synthetic Cathinones In

Neurotoxicology 75 (2019) 158–173 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Neurotoxicology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/neuro Structure-cytotoxicity relationship profile of 13 synthetic cathinones in differentiated human SH-SY5Y neuronal cells T ⁎ Jorge Soaresa, , Vera Marisa Costaa, Helena Gasparb,c, Susana Santosd,e, Maria de Lourdes Bastosa, ⁎ Félix Carvalhoa, João Paulo Capelaa,f, a UCIBIO, REQUIMTE (Rede de Química e Tecnologia), Laboratório de Toxicologia, Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Faculdade de Farmácia, Universidade do Porto, Portugal b BioISI – Instituto de Biossistemas e Ciências Integrativas, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal c MARE - Centro de Ciências do Mar e do Ambiente, Escola Superior de Turismo e Tecnologia do Mar, Instituto Politécnico de Leiria, Portugal d Centro de Química e Bioquímica (CQB), Departamento de Química e Bioquímica, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal e Centro de Química Estrutural, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal f FP-ENAS (Unidade de Investigação UFP em Energia, Ambiente e Saúde), CEBIMED (Centro de Estudos em Biomedicina), Faculdade de Ciências da Saúde, Universidade Fernando Pessoa, Portugal ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Synthetic cathinones also known as β-keto amphetamines are a new group of recreational designer drugs. We Synthetic cathinones aimed to evaluate the cytotoxic potential of thirteen cathinones lacking the methylenedioxy ring and establish a Classical amphetamines putative structure-toxicity profile using differentiated SH-SY5Y cells, as well as to compare their toxicity to that Cytotoxicity of amphetamine (AMPH) and methamphetamine (METH). Cytotoxicity assays [mitochondrial 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2- SH-SY5Y cells thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) reduction and lysosomal neutral red (NR) uptake] per- Structure-toxicity relationship formed after a 24-h or a 48-h exposure revealed for all tested drugs a concentration-dependent toxicity. -

Cerebral Histamine H1 Receptor Binding Potential Measured With

Cerebral Histamine H1 Receptor Binding Potential Measured with PET Under a Test Dose of Olopatadine, an Antihistamine, Is Reduced After Repeated Administration of Olopatadine Michio Senda1, Nobuo Kubo2, Kazuhiko Adachi3, Yasuhiko Ikari1,4, Keiichi Matsumoto1, Keiji Shimizu1, and Hideyuki Tominaga1 1Division of Molecular Imaging, Institute of Biomedical Research and Innovation, Kobe, Japan; 2Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Kansai Medical University, Osaka, Japan; 3Department of Mechanical Engineering, Kobe University, Kobe, Japan; and 4Micron, Inc., Kobe, Japan Some antihistamine drugs that are used for rhinitis and pollinosis have a sedative effect as they enter the brain and block the H1 Antihistamines are widely used as a medication for receptor, potentially causing serious accidents. Receptor occu- common allergic disorders such as seasonal pollinosis, pancy has been measured with PET under single-dose adminis- tration in humans to classify antihistamines as more sedating or chronic rhinitis, and urticaria. Some antihistamine drugs as less sedating (or nonsedating). In this study, the effect of re- have a sedative side effect as they enter the brain and block peated administration of olopatadine, an antihistamine, on the histamine H1 receptor, potentially causing traffic accidents cerebral H1 receptor was measured with PET. Methods: A total and other serious events, but the sedative effect is difficult to of 17 young men with rhinitis underwent dynamic brain PET with evaluate because of a large variation in neuropsychological 11 C-doxepin at baseline, under an initial single dose of 5 mg of measures and subjective symptoms. Measurement of cere- olopatadine (acute scan), and under another 5-mg dose after re- 11 peated administration of olopatadine at 10 mg/d for 4 wk (chronic bral histamine H1 receptor occupancy using PET with C- doxepin under a single administration of antihistamines has scan). -

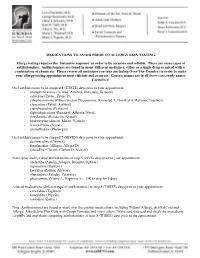

MEDICATIONS to AVOID PRIOR to ALLERGY SKIN TESTING Allergy

MEDICATIONS TO AVOID PRIOR TO ALLERGY SKIN TESTING Allergy testing requires the ‘histamine response’ in order to be accurate and reliable. There are many types of antihistamines. Antihistamines are found in many different medicines, either as a single drug or mixed with a combination of chemicals. Please review all medicines you take (including Over-The-Counter) in order to make your allergy testing appointment most efficient and accurate. Generic names are in all lower case, trade names Capitalized. Oral antihistamines to be stopped 3 (THREE) days prior to your appointment: - brompheniramine (Actifed, Atrohist, Dimetapp, Drixoral) - cetirizine (Zyrtec, Zyrtec D) - chlopheniramine (Chlortrimeton, Deconamine, Kronofed A, Novafed A, Rynatan, Tussinex) - clemastine (Tavist, Antihist) - cyproheptadine (Periactin) - diphenhydramine (Benadryl, Allernix, Nytol) - doxylamine (Bendectin, Nyquil) - hydroxyzine (Atarax, Marax, Vistaril) - levocetirizine (Xyzal) - promethazine (Phenergan) Oral antihistamines to be stopped 7 (SEVEN) days prior to your appointment: - desloratadine (Clarinex) - fexofenadine (Allegra, Allegra D) - loratadine (Claritin, Claritin D, Alavert) Nose spray and eye drop antihistamines to stop 5 (FIVE) days prior to your appointment: - azelastine (Astelin, Astepro, Dymista, Optivar) - bepotastine (Bepreve) - ketotifen (Zaditor, Alaway) - olapatadine (Pataday, Patanase) - pheniramine (Visine A, Naphcon A) – OK to stop for 2 days Antacid medications (different type of antihistamine) to stop 3 (THREE) days prior to your appointment: - cimetidine (Tagamet) - famotidine (Pepcid) - ranitidine (Zantac) Note: Antihistamines are found in many over the counter medications, including Tylenol Allergy, Actifed Cold and Allergy, Alka-Seltzer Plus Cold with Cough Formula, and many others. Make sure you read and check the ingredients carefully and stop those containing antihistamines at least 3 (THREE) days prior to the appointment. -

Low-Dose Doxepin for Treatment of Pruritus in Patients on Hemodialysis

DIALYSIS Low-Dose Doxepin for Treatment of Pruritus in Patients on Hemodialysis Fatemeh Pour-Reza-Gholi,1 Alireza Nasrollahi,2 Ahmad Firouzan,1 Ensieh Nasli Esfahani,1 Farhat Farrokhi3 1Department of Nephrology, Introduction. Pruritus is one of the frequent discomforting Shaheed Labbafinejad complications in patients with end-stage renal disease. We Medical Center & Urology and prospectively evaluated the effectiveness of doxepin, an H1-receptor Nephrology Research Center, antagonist of histamine, in patients with pruritus resistant to Shaheed Beheshti Medical University, Tehran, Iran conventional treatment. 2Department of Nephrology, Materials and Methods. A randomized controlled trial with a Shohada-e-Tajrish Hospital, crossover design was performed on 24 patients in whom other Shaheed Beheshti Medical etiologic factors of pruritus had been ruled out. They were assigned University, Tehran, Iran into 2 groups and received either placebo or oral doxepin, 10 mg, 3Urology and Nephrology Research Center, Shaheed twice a day for 1 week. After a 1-week washout period, the 2 groups Beheshti Medical University, were treated conversely. Subjective outcome was determined by Tehran, Iran asking the patients described their pruritus as completely improved, relatively improved, or remained unchanged/worsened. Keywords. pruritus, doxepin, Results. Complete resolution of pruritus was reported in end-stage renal disease, 14 patients (58.3%) with doxepin and 2 (8.3%) with placebo dialysis (P < .001). Relative improvement was observed in 7 (29.2%) and 4 (16.7%), respectively. Overall, the improving effect of doxepin on Original Paper pruritus was seen in 87.5% of the patients. Twelve patients (50.0%) complained of drowsiness that alleviated in all cases after 2 days in average. -

Psychedelics in Psychiatry: Neuroplastic, Immunomodulatory, and Neurotransmitter Mechanismss

Supplemental Material can be found at: /content/suppl/2020/12/18/73.1.202.DC1.html 1521-0081/73/1/202–277$35.00 https://doi.org/10.1124/pharmrev.120.000056 PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEWS Pharmacol Rev 73:202–277, January 2021 Copyright © 2020 by The Author(s) This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC Attribution 4.0 International license. ASSOCIATE EDITOR: MICHAEL NADER Psychedelics in Psychiatry: Neuroplastic, Immunomodulatory, and Neurotransmitter Mechanismss Antonio Inserra, Danilo De Gregorio, and Gabriella Gobbi Neurobiological Psychiatry Unit, Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada Abstract ...................................................................................205 Significance Statement. ..................................................................205 I. Introduction . ..............................................................................205 A. Review Outline ........................................................................205 B. Psychiatric Disorders and the Need for Novel Pharmacotherapies .......................206 C. Psychedelic Compounds as Novel Therapeutics in Psychiatry: Overview and Comparison with Current Available Treatments . .....................................206 D. Classical or Serotonergic Psychedelics versus Nonclassical Psychedelics: Definition ......208 Downloaded from E. Dissociative Anesthetics................................................................209 F. Empathogens-Entactogens . ............................................................209