Capability of Solar Electric Propulsion for Planetary Missions Giuseppe D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orbit Options for an Orion-Class Spacecraft Mission to a Near-Earth Object

Orbit Options for an Orion-Class Spacecraft Mission to a Near-Earth Object by Nathan C. Shupe B.A., Swarthmore College, 2005 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Aerospace Engineering Sciences 2010 This thesis entitled: Orbit Options for an Orion-Class Spacecraft Mission to a Near-Earth Object written by Nathan C. Shupe has been approved for the Department of Aerospace Engineering Sciences Daniel Scheeres Prof. George Born Assoc. Prof. Hanspeter Schaub Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Shupe, Nathan C. (M.S., Aerospace Engineering Sciences) Orbit Options for an Orion-Class Spacecraft Mission to a Near-Earth Object Thesis directed by Prof. Daniel Scheeres Based on the recommendations of the Augustine Commission, President Obama has pro- posed a vision for U.S. human spaceflight in the post-Shuttle era which includes a manned mission to a Near-Earth Object (NEO). A 2006-2007 study commissioned by the Constellation Program Advanced Projects Office investigated the feasibility of sending a crewed Orion spacecraft to a NEO using different combinations of elements from the latest launch system architecture at that time. The study found a number of suitable mission targets in the database of known NEOs, and pre- dicted that the number of candidate NEOs will continue to increase as more advanced observatories come online and execute more detailed surveys of the NEO population. -

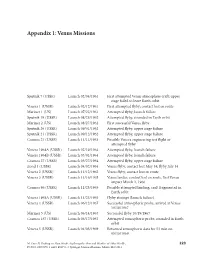

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

An Assessment of Aerocapture and Applications to Future Missions

Post-Exit Atmospheric Flight Cruise Approach An Assessment of Aerocapture and Applications to Future Missions February 13, 2016 National Aeronautics and Space Administration An Assessment of Aerocapture Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California and Applications to Future Missions Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology for Planetary Science Division Science Mission Directorate NASA Work Performed under the Planetary Science Program Support Task ©2016. All rights reserved. D-97058 February 13, 2016 Authors Thomas R. Spilker, Independent Consultant Mark Hofstadter Chester S. Borden, JPL/Caltech Jessie M. Kawata Mark Adler, JPL/Caltech Damon Landau Michelle M. Munk, LaRC Daniel T. Lyons Richard W. Powell, LaRC Kim R. Reh Robert D. Braun, GIT Randii R. Wessen Patricia M. Beauchamp, JPL/Caltech NASA Ames Research Center James A. Cutts, JPL/Caltech Parul Agrawal Paul F. Wercinski, ARC Helen H. Hwang and the A-Team Paul F. Wercinski NASA Langley Research Center F. McNeil Cheatwood A-Team Study Participants Jeffrey A. Herath Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Caltech Michelle M. Munk Mark Adler Richard W. Powell Nitin Arora Johnson Space Center Patricia M. Beauchamp Ronald R. Sostaric Chester S. Borden Independent Consultant James A. Cutts Thomas R. Spilker Gregory L. Davis Georgia Institute of Technology John O. Elliott Prof. Robert D. Braun – External Reviewer Jefferey L. Hall Engineering and Science Directorate JPL D-97058 Foreword Aerocapture has been proposed for several missions over the last couple of decades, and the technologies have matured over time. This study was initiated because the NASA Planetary Science Division (PSD) had not revisited Aerocapture technologies for about a decade and with the upcoming study to send a mission to Uranus/Neptune initiated by the PSD we needed to determine the status of the technologies and assess their readiness for such a mission. -

Achievements of Hayabusa2: Unveiling the World of Asteroid by Interplanetary Round Trip Technology

Achievements of Hayabusa2: Unveiling the World of Asteroid by Interplanetary Round Trip Technology Yuichi Tsuda Project Manager, Hayabusa2 Japan Aerospace ExplorationAgency 58th COPUOS, April 23, 2021 Lunar and Planetary Science Missions of Japan 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 Future Plan Moon 2007 Kaguya 1990 Hiten SLIM Lunar-A × Venus 2010 Akatsuki 2018 Mio 1998 Nozomi × Planets Mercury (Mars) 2010 IKAROS Venus MMX Phobos/Mars 1985 Suisei 2014 Hayabusa2 Small Bodies Asteroid Ryugu 2003 Hayabusa 1985 Sakigake Asteroid Itokawa Destiny+ Comet Halley Comet Pheton 2 Hayabusa2 Mission ✓ Sample return mission to a C-type asteroid “Ryugu” ✓ 5.2 billion km interplanetary journey. Launch Earth Gravity Assist Ryugu Arrival MINERVA-II-1 Deployment Dec.3, 2014 Sep.21, 2018 Dec.3, 2015 Jun.27, 2018 MASCOT Deployment Oct.3, 2018 Ryugu Departure Nov.13.2019 Kinetic Impact Earth Return Second Dec.6, 2020 Apr.5, 2019 Target Markers Orbiting Touchdown Sep.16, 2019 Jul,11, 2019 First Touchdown Feb.22, 2019 MINERVA-II-2 Orbiting MD [D VIp srvlxp #534<# Oct.2, 2019 Hayabusa2 Spacecraft Overview Deployable Xband Xband Camera (DCAM3) HGA LGA Xband Solar Array MGA Kaba nd Ion Engine HGA Panel RCS thrusters ×12 ONC‐T, ONC‐W1 Star Trackers Near Infrared DLR MASCOT Spectrometer (NIRS3) Lander Thermal Infrared +Z Imager (TIR) Reentry Capsule +X MINERVA‐II Small Carry‐on +Z LIDAR ONC‐W2 +Y Rovers Impactor (SCI) +X Sampler Horn Target +Y Markers ×5 Launch Mass: 609kg Ion Engine: Total ΔV=3.2km/s, Thrust=5-28mN (variable), Specific Impulse=2800- 3000sec. (4 thrusters, mounted on two-axis gimbal) Chemical RCS: Bi-prop. -

THE LANDSCAPE of COMET HALLEY Hungarian Academy of Sciences CENTRAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE for PHYSICS

KFKI 1939-35/C E. MERÉNYI L. FÖLDY K. SZEGŐ I. TÓTH A. KONDOR THE LANDSCAPE OF COMET HALLEY Hungarian Academy of Sciences CENTRAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR PHYSICS BUDAPEST KFKI-1989-35/C PREPRINT THE LANDSCAPE OF COMET HALLEY E. MERÉNYI, L. FÖLDY, K. SZEGŐ. I. TÓTH', A. KONDOR Central Research Institute for Physics H-1626 Budapest 114, P.O.B. 49 'Konkoly Thege Observatory H-1625 Budapest, P.O.B. 67 Comets in Post Hal ley area Bamberg (FRG). 24 28 April 1989 HU ISSN 0368 6330 E. Merényi, L. Földy. К. Szegő, I. Tóth. A. Kondor: The landscape of cornel Halley KFKM989 35/C ABSTRACT In this paper the three dimensional model of P/Halley's nucleus is constructed based on the results of the imaging experiments It has the following major characteristics: the overai' sizes are 7 2 km, 722 km, 15.3 km, its volume is 365 km3, the ratios of the inertfal momenta are 34:33:1, the longest Inorttal axis is siiyhlly inclined to the geometrical axis of the body. 3 3° in latitude and 1.1° In longitude if the geometrical axis is at zero latitude and longitude The shape is very irregular, it is not close to any regular body e g to a tri axial ellipsoid Several features on the images are interpreted as local slope variations of the nucleus. Э. Мерени; Л. Фёлди, К. Сегё, И. Тот, Л. Кондор: Форма и поверхность ядра кометы Галлея. КГКТ-198<?-35/С АННОТАЦИЯ Описывается трехмерная модель ядра кометы Галлея, основывающаяся на резуль татах телевизионного эксперимента КА "Вега". -

Gravity-Assist Trajectories to Jupiter Using Nuclear Electric Propulsion

AAS 05-398 Gravity-Assist Trajectories to Jupiter Using Nuclear Electric Propulsion ∗ ϒ Daniel W. Parcher ∗∗ and Jon A. Sims ϒϒ This paper examines optimal low-thrust gravity-assist trajectories to Jupiter using nuclear electric propulsion. Three different Venus-Earth Gravity Assist (VEGA) types are presented and compared to other gravity-assist trajectories using combinations of Earth, Venus, and Mars. Families of solutions for a given gravity-assist combination are differentiated by the approximate transfer resonance or number of heliocentric revolutions between flybys and by the flyby types. Trajectories that minimize initial injection energy by using low resonance transfers or additional heliocentric revolutions on the first leg of the trajectory offer the most delivered mass given sufficient flight time. Trajectory families that use only Earth gravity assists offer the most delivered mass at most flight times examined, and are available frequently with little variation in performance. However, at least one of the VEGA trajectory types is among the top performers at all of the flight times considered. INTRODUCTION The use of planetary gravity assists is a proven technique to improve the performance of interplanetary trajectories as exemplified by the Voyager, Galileo, and Cassini missions. Another proven technique for enhancing the performance of space missions is the use of highly efficient electric propulsion systems. Electric propulsion can be used to increase the mass delivered to the destination and/or reduce the trip time over typical chemical propulsion systems.1,2 This technology has been demonstrated on the Deep Space 1 mission 3 − part of NASA’s New Millennium Program to validate technologies which can lower the cost and risk and enhance the performance of future missions. -

Technologies for Future Venus Exploration

September 9, 2009 WHITE PAPER TO THE NRC DECADAL SURVEY INNER PLANETS SUB–PANEL ON TECHNOLOGIES FOR FUTURE VENUS EXPLORATION by Tibor Balint1 & James Cutts1 (818) 354-1105 & (818) 354-4120 [email protected] & [email protected] and Mark Bullock2, James Garvin3, Stephen Gorevan4, Jeffery Hall1, Peter Hughes3, Gary Hunter4, Satish Khanna1, Elizabeth Kolawa1, Viktor Kerzhanovich1, Ethiraj Venkatapathy5 1Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology; 2Southwest Research Institute; 3NASA–Goddard Space Flight Center; 3Honeybee Robotics; 4NASA–Glenn Research Center; 5NASA–Ames Research Center ABSTRACT The purpose of this white paper is to provide an overview to the NRC Decadal Survey Inner Planets Sub–Panel on key technologies required for future Venus exploration missions. It covers both heritage technologies and identifies new technologies to enable future missions in all three mission classes. The technologies will focus on mission enabling and enhancing capabilities for in situ missions, because most orbiter related sub–systems are considered heritage technologies. This white paper draws heavily on the recently completed Venus Flagship Mission study that identified key technologies required to implement its Design Reference Mission and other important mission options. The highest priority technologies and capabilities for the Venus Flagship Design Reference mission consist of: surface sample acquisition and handling; mechanical implementation of a rotating pressure vessel; a rugged–terrain landing system; and a large scale environmental test chamber to test these technologies under relevant Venus–like conditions. Other longer–term Venus Flagship Mission options will require additional new capabilities, namely a Venus–specific Radioisotope Power System; active refrigeration, high temperature electronics and advanced thermal insulation. -

Securing Japan an Assessment of Japan´S Strategy for Space

Full Report Securing Japan An assessment of Japan´s strategy for space Report: Title: “ESPI Report 74 - Securing Japan - Full Report” Published: July 2020 ISSN: 2218-0931 (print) • 2076-6688 (online) Editor and publisher: European Space Policy Institute (ESPI) Schwarzenbergplatz 6 • 1030 Vienna • Austria Phone: +43 1 718 11 18 -0 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.espi.or.at Rights reserved - No part of this report may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or for any purpose without permission from ESPI. Citations and extracts to be published by other means are subject to mentioning “ESPI Report 74 - Securing Japan - Full Report, July 2020. All rights reserved” and sample transmission to ESPI before publishing. ESPI is not responsible for any losses, injury or damage caused to any person or property (including under contract, by negligence, product liability or otherwise) whether they may be direct or indirect, special, incidental or consequential, resulting from the information contained in this publication. Design: copylot.at Cover page picture credit: European Space Agency (ESA) TABLE OF CONTENT 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background and rationales ............................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Objectives of the Study ................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Methodology -

Life on Venus, and How to Explore Venus with High-Temperature Electronics Carl-Mikael Zetterling [email protected]

Life on Venus, and How to Explore Venus with High-Temperature Electronics Carl-Mikael Zetterling [email protected] www.WorkingonVenus.se Outline Life on Venus (phosphine in the clouds) Previous missions to Venus Life on Venus (photos from the ground) High temperature electronics Future missions to Venus, including Working on Venus (KTH Project 2014 - 2018) www.WorkingonVenus.se 3 Phosphine gas in the cloud decks of Venus Trace amounts of phosphine (20 ppb, PH3) seen by the ALMA and JCMT telescopes, with millimetre wave spectral detection 4 Phosphine gas in the cloud decks of Venus 5 Phosphine gas in the cloud decks of Venus https://www.nature.com/articles/s41550-020-1174-4 https://arxiv.org/pdf/2009.06499.pdf https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/14/science/venus-life- clouds.html?smtyp=cur&smid=fb-nytimesfindings https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/is-there-life-on- venus-these-missions-could-find-it/ 6 Did NASA detect phosphine 1978? Pioneer 13 Large Probe Neutral Mass Spectrometer (LNMS) https://www.livescience.com/life-on-venus-pioneer-13.html 7 Why Venus? From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository Our closest planet, but least known Similar to earth in size and core, has an atmosphere Volcanoes Interesting for climate modeling Venus Long-life Surface Package (ultimate limit of global warming) C. Wilson, C.-M. Zetterling, W. T. Pike IAC-17-A3.5.5, Paper 41353 arXiv:1611.03365v1 www.WorkingonVenus.se 8 Venus Atmosphere 96% CO2 (Also sulphuric acids) Pressure of 92 bar (equivalent to 1000 m water) Temperature 460 °C From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository Difficult to explore Life is not likely www.WorkingonVenus.se 9 Previous Missions Venera 1 – 16 (1961 – 1983) USSR Mariner 2 (1962) NASA, USA Pioneer (1978 – 1992) NASA, USA Magellan (1989) NASA, USA Venus Express (2005 - ) ESA, Europa From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository Akatsuki (2010) JAXA, Japan www.WorkingonVenus.se 10 Steps to lunar and planetary exploration: 1. -

Chemistry of Small Components of Upper Shells of Venus

Lunar and Planetary Science XXIX 1003.pdf CHEMISTRY OF SMALL COMPONENTS OF UPPER SHELLS OF VENUS. B.M. Andreichikov, Space Research Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, 117810, Profsojuznaja st. 84/32,Moscow, Russia. Received by means of the VEGA 1, VEGA 2, a water mass (~ 4,5 ´ 1022 g, in the manner of GALILEO spacecrafts, information on Venus [1– hydro-xylgroups). 9] has vastly increased our knowledge about this (5) The possibility of presence in atmosphere of planet, but has introduced new questions connected planet of oxidizes of phosphorus is shown. (6) It with the chemistry of the atmosphere, the surface, had been revealed that they form of the atmos- and interaction processes. Additionally last publi- pheric components mixing ratio vertical profiles cations of the data of the optical spectroscopy [9– participating actively in reactions of the oxidation- 13] have revealed else greater divergence of them reduction. (7) The possibility of formation at a rate with results of the gas chromatography [14–17], of of 11–12 km of traces of aerosol of the layered the mass- spectrometers [18] and of the others of polymers (P2O5)n is shown. (8) It was revealed, that the contact measurements methods [6]. It had been seeming discord of results of direct measurements reported in works [7,8] about finding in the Ve- in the atmosphere of Venus is connected with the nusian night clouds of aerosol which contain a difference of chemical processes daytime and in the phosphor. The nephelometeric measurements [19] night, stipulated by the influence (of deeper at a have shown also that lower, the most dense clouds day time) of photochemical reactions products in layer an (47,5–50,5 km) is formed in the night and the upper troposphere. -

Study of a Crew Transfer Vehicle Using Aerocapture for Cycler Based Exploration of Mars by Larissa Balestrero Machado a Thesis S

Study of a Crew Transfer Vehicle Using Aerocapture for Cycler Based Exploration of Mars by Larissa Balestrero Machado A thesis submitted to the College of Engineering and Science of Florida Institute of Technology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Aerospace Engineering Melbourne, Florida May, 2019 © Copyright 2019 Larissa Balestrero Machado. All Rights Reserved The author grants permission to make single copies ____________________ We the undersigned committee hereby approve the attached thesis, “Study of a Crew Transfer Vehicle Using Aerocapture for Cycler Based Exploration of Mars,” by Larissa Balestrero Machado. _________________________________________________ Markus Wilde, PhD Assistant Professor Department of Aerospace, Physics and Space Sciences _________________________________________________ Andrew Aldrin, PhD Associate Professor School of Arts and Communication _________________________________________________ Brian Kaplinger, PhD Assistant Professor Department of Aerospace, Physics and Space Sciences _________________________________________________ Daniel Batcheldor Professor and Head Department of Aerospace, Physics and Space Sciences Abstract Title: Study of a Crew Transfer Vehicle Using Aerocapture for Cycler Based Exploration of Mars Author: Larissa Balestrero Machado Advisor: Markus Wilde, PhD This thesis presents the results of a conceptual design and aerocapture analysis for a Crew Transfer Vehicle (CTV) designed to carry humans between Earth or Mars and a spacecraft on an Earth-Mars cycler trajectory. The thesis outlines a parametric design model for the Crew Transfer Vehicle and presents concepts for the integration of aerocapture maneuvers within a sustainable cycler architecture. The parametric design study is focused on reducing propellant demand and thus the overall mass of the system and cost of the mission. This is accomplished by using a combination of propulsive and aerodynamic braking for insertion into a low Mars orbit and into a low Earth orbit. -

JAXA's Planetary Exploration Plan

Planetary Exploration and International Collaboration Institute of Space and Astronautical Science Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency Yoshio Toukaku, Director for International Strategy and Coordination Naoya Ozaki, Assistant Professor, Dept of Spacecraft Engineering ISAS/JAXA September, 2019 The Path Japanese Planetary Exploration 1985 1995 2010 2018 Sakigake/ Nozomi Akatsuki BepiColombo Suisei MMO/MPO Comet flyby Planned and Venus Climate Mercury Orbiter launched Mars Orbiter orbiter Asteroid Sample Asteroid Sample Martian Moons Lunar probe Return Mission Return Mission explorer Hiten Hayabusa Hayabusa2 MMX 1992 2003 2014 2020s (TBD) Recent Science Missions HAYABUSA 2003-2010 HINODE(SOLAR-B)2006- KAGUYASELENE)2007-2009 Asteroid Explorer SolAr OBservAtion Lunar Exploration AKATSUKI 2010- Venus Meteorology IKAROS 2010 HisAki 2013 SolAr SAil PlAnetary atmosphere HAYABUSA2 2014-2020 Hitomi(ASTRO-H) 2016 ArAse (ERG) 2016 Asteroid Explorer X-Ray Astronomy Van Allen Belt proBe Hayabusa & Hayabusa 2 Asteroid Sample Return Missions “Hayabusa” spacecraft brought back the material of Asteroid Itokawa while establishing innovative ion engines. “Hayabusa2”, while utilizing the experience cultivated in “Hayabusa”, has arrived at the C type Asteroid Ryugu in order to elucidate the origin and evolution of the solar system and primordial materials that would have led to emergence of life. Hayabusa Hayabusa2 Target Itokawa Ryugu Launch 2003 2014 Arrival 2005 2018 Return 2010 2020 ©JAXA Asteroid Ryugu 6 Martian Moons eXploration (MMX) Sample return from Marian moon for detailed analysis. Strategic L-Class A key element in the ISAS roadmap for small body exploration. Phase A n Science Objectives 1. Origin of Mars satellites. - Captured asteroids? - Accreted debris resulting from a giant impact? 2. Preparatory processes enabling to the habitability of the solar system.