Space Science and Exploration: a Historical Perspective' J.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Examination of Vietnam and Space

Space Policy 47 (2019) 78e84 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Space Policy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/spacepol An Examination of Vietnam and Space Travis S. Cottom SAIC, 1911 N. Fort Myer Drive, Suite 500, Arlington, VA 22209, USA article info abstract Article history: Vietnam is slowly expanding its presence in space and to better understand where Vietnam is going in Received 28 February 2018 the future, a thorough examination that incorporates several factors must be completed. This article Received in revised form examines Vietnam's history in space, its space strategy, the organizational structure of its space program, 26 June 2018 how Vietnam is expanding its presence in space, and how Vietnam plans to use space for national se- Accepted 28 July 2018 curity purposes. The article also reviews Vietnam's cooperation with other space nations where they are Available online 17 August 2018 substantially benefiting from programs aimed at advancing the capabilities of emerging space nations. The article ends with potential areas that Vietnam and the United States can cooperate to advance both Keywords: fl Vietnam states capabilities in space while at the same time limiting Chinese in uence in Vietnam. © Space program 2018 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Satellites National security Emerging space nations 1. Introduction 23 July 1980, Pham Tuan became the first Vietnamese citizen to fly in space [3]. Following the spaceflight, Vietnam used satellite data The number of nations investing in space has greatly increased provided by the United Nations Development Program for sus- during the 21st century as the availability and commercialization of tainable development purposes [4]. -

Part 2 Almaz, Salyut, And

Part 2 Almaz/Salyut/Mir largely concerned with assembly in 12, 1964, Chelomei called upon his Part 2 Earth orbit of a vehicle for circumlu- staff to develop a military station for Almaz, Salyut, nar flight, but also described a small two to three cosmonauts, with a station made up of independently design life of 1 to 2 years. They and Mir launched modules. Three cosmo- designed an integrated system: a nauts were to reach the station single-launch space station dubbed aboard a manned transport spacecraft Almaz (“diamond”) and a Transport called Siber (or Sever) (“north”), Logistics Spacecraft (Russian 2.1 Overview shown in figure 2-2. They would acronym TKS) for reaching it (see live in a habitation module and section 3.3). Chelomei’s three-stage Figure 2-1 is a space station family observe Earth from a “science- Proton booster would launch them tree depicting the evolutionary package” module. Korolev’s Vostok both. Almaz was to be equipped relationships described in this rocket (a converted ICBM) was with a crew capsule, radar remote- section. tapped to launch both Siber and the sensing apparatus for imaging the station modules. In 1965, Korolev Earth’s surface, cameras, two reentry 2.1.1 Early Concepts (1903, proposed a 90-ton space station to be capsules for returning data to Earth, 1962) launched by the N-1 rocket. It was and an antiaircraft cannon to defend to have had a docking module with against American attack.5 An ports for four Soyuz spacecraft.2, 3 interdepartmental commission The space station concept is very old approved the system in 1967. -

Aerospace Facts and Figures 1979/80 Lunar Landing 1969-1979

Aerospace Facts and Figures 1979/80 Lunar Landing 1969-1979 This 27th annual edition of Aero space Facts and Figures commem orates the 1Oth anniversary of man's initial landing on the moon, which occurred on July 20, 1969 during the Apollo 11 mission. Neil Armstrong and Edwin E. Aldrin were the first moonwalkers and their Apollo 11 teammate was Com mand Module Pilot Michael Collins. Shown above is NASA's 1Oth anni versary commemorative logo; created by artist Paull Calle, it de picts astronaut Armstrong pre paring to don his helmet prior to the historic Apollo 11 launch. On the Cover: James J. Fi sher's cover art symboli zes th e Earth/ moon relationship and man's efforts to expl ore Earth 's ancien t sa tellite. Aerospace Facts and Figures m;ji8Q Aerospace Facts and Figures 1979/80 AEROSPACE INDUSTRIES ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA, INC. 1725 DeSales Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 Published by Aviation Week & Space Technology A MCGRAW-HILL PUBLICATION 1221 Avenue of the Americas New York, N.Y. 10020 (212) 997-3289 $6.95 Per Copy Copyright, July 1979 by Aerospace Industries Association of America, Inc. Library of Congress Catalog No. 46-25007 Compiled by Economic Data Service Aerospace Research Center Aerospace Industries Association of America, Inc. 1725 De Sales Street, N. W., Washington, D.C. 20036 (202) 347-2315 Director Allen H. Skaggs Chief Statistician Sally H. Bath Acknowledgments Air Transport Association Civil Aeronautics Board Export-Import Bank of the United States Federal Trade Commission General Aviation Manufacturers Association International Air Transport Association International Civil Aviation Organization National Aeronautics and Space Administration National Science Foundation U. -

Dead Cosmonauts >> Misc

James Oberg's Pioneering Space powered by Uncovering Soviet Disasters >> Aerospace Safety & Accidents James Oberg >> Astronomy >> Blogs Random house, New York, 1988 >> Chinese Space Program Notes labeled "JEO" added to electronic version in 1998 >> Flight to Mars >> Jim's FAQ's >> Military Space Chapter 10: Dead Cosmonauts >> Misc. Articles Page 156-176 >> National Space Policy >> Other Aerospace Research >> Reviews The family of Senior Lieutenant Bondarenko is to be provided with everything necessary, as befits the >> Russian Space Program family of a cosmonaut. --Special Order, signed by Soviet Defense Minister R. D. Malinovskiy, April 16, >> Space Attic NEW 1961, classified Top Secret. NOTE: Prior to 1986 no Soviet book or magazine had ever mentioned the >> Space Folklore existence of a cosmonaut named Valentin Bondarenko. >> Space History >> Space Operations In 1982, a year after the publication of my first book, Red Star in Orbit. I received a wonderful picture >> Space Shuttle Missions from a colleague [JEO: Arthur Clarke, in fact] who had just visited Moscow. The photo showed >> Space Station cosmonaut Aleksey Leonov, hero of the Soviet Union, holding a copy of my book-- and scowling. >> Space Tourism Technical Notes >> Leonov was frowning at a picture of what I called the "Sochi Six," the Russian equivalent of our "original >> Terraforming seven" Mercury astronauts. They were the top of the first class of twenty space pioneers, the best and the boldest of their nation, the ones destined to ride the first manned missions. The picture was taken at the Black Sea resort called Sochi in May 1961, a few weeks after Yuriy Gagarin's history-making flight. -

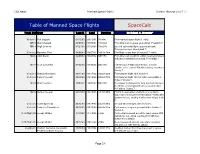

Table of Manned Space Flights Spacecalc

CBS News Manned Space Flights Current through STS-117 Table of Manned Space Flights SpaceCalc Total: 260 Crew Launch Land Duration By Robert A. Braeunig* Vostok 1 Yuri Gagarin 04/12/61 04/12/61 1h:48m First manned space flight (1 orbit). MR 3 Alan Shepard 05/05/61 05/05/61 15m:22s First American in space (suborbital). Freedom 7. MR 4 Virgil Grissom 07/21/61 07/21/61 15m:37s Second suborbital flight; spacecraft sank, Grissom rescued. Liberty Bell 7. Vostok 2 Guerman Titov 08/06/61 08/07/61 1d:01h:18m First flight longer than 24 hours (17 orbits). MA 6 John Glenn 02/20/62 02/20/62 04h:55m First American in orbit (3 orbits); telemetry falsely indicated heatshield unlatched. Friendship 7. MA 7 Scott Carpenter 05/24/62 05/24/62 04h:56m Initiated space flight experiments; manual retrofire error caused 250 mile landing overshoot. Aurora 7. Vostok 3 Andrian Nikolayev 08/11/62 08/15/62 3d:22h:22m First twinned flight, with Vostok 4. Vostok 4 Pavel Popovich 08/12/62 08/15/62 2d:22h:57m First twinned flight. On first orbit came within 3 miles of Vostok 3. MA 8 Walter Schirra 10/03/62 10/03/62 09h:13m Developed techniques for long duration missions (6 orbits); closest splashdown to target to date (4.5 miles). Sigma 7. MA 9 Gordon Cooper 05/15/63 05/16/63 1d:10h:20m First U.S. evaluation of effects of one day in space (22 orbits); performed manual reentry after systems failure, landing 4 miles from target. -

Association of Space Explorers 10Th Planetary Congress Moscow/Lake Baikal, Russia 1994

Association of Space Explorers 10th Planetary Congress Moscow/Lake Baikal, Russia 1994 Commemorative Poster Signature Key Loren Acton Viktor Afanasyev Toyohiro Akiyama STS 51F Soyuz TM-11 Soyuz TM-11 Vladimir Aksyonov Sultan bin Salman al-Saud Buzz Aldrin Soyuz 22, Soyuz T-2 STS 51G Gemini 12, Apollo 11 Alexander Alexandrov Anatoli Artsebarsky Oleg Atkov Soyuz T-9, Soyuz TM-3 Soyuz TM-12 Soyuz T-10 Toktar Aubakirov Alexander Balandin Georgi Beregovoi Soyuz TM-13 Soyuz TM-9 Soyuz 3 Anatoli Berezovoi Karol Bobko Roberta Bondar Soyuz T-5 STS 6, STS 51D, STS 51J STS 42 Scott Carpenter John Creighton Vladimir Dzhanibekov Mercury 7 STS 51G, STS 36, STS 48 Soyuz 27, Soyuz 39, Soyuz T-6 Soyuz T-12, Soyuz T-13 John Fabian Mohammed Faris Bertalan Farkas STS 7, STS 41G Soyuz TM-3 Soyuz 36 Anatoli Filipchenko Dirk Frimout Owen Garriott Soyuz 7, Soyuz 16 STS 45 Skylab III, STS 9 Yuri Glazkov Georgi Grechko Alexei Gubarev Soyuz 24 Soyuz 17, Soyuz 26 Soyuz 17, Soyuz 28 Soyuz T-14 Miroslaw Hermaszewski Alexander Ivanchenkov Alexander Kaleri Soyuz 30 Soyuz 29, Soyuz T-6 Soyuz TM-14 Yevgeni Khrunov Pyotr Klimuk Vladimir Kovolyonok Soyuz 5 Soyuz 13, Soyuz 18, Soyuz 30 Soyuz 25, Soyuz 29, Soyuz T-4 Valeri Kubasov Alexei Leonov Byron Lichtenberg Soyuz 6, Apollo-Soyuz Voskhod 2, Apollo-Soyuz STS 9, STS 45 Soyuz 36 Don Lind Jack Lousma Vladimir Lyakhov STS 51B Skylab III, STS 3 Soyuz 32, Soyuz T-9 Soyuz TM-6 Oleg Makarov Gennadi Manakov Jon McBride Soyuz 12, Soyuz 27, Soyuz T-3 Soyuz TM-10, Soyuz TM-16 STS 41G Ulf Merbold Mamoru Mohri Donald Peterson STS 9, -

XIV Congress

Association of Space Explorers 14th Planetary Congress Brussels, Belgium 1998 Commemorative Poster Signature Key Loren Acton Toyohiro Akiyama Alexander Alexandrov (Bul.) STS 51F Soyuz TM-11 Soyuz TM-5 Oleg Atkov Toktar Aubakirov Yuri Baturin Soyuz T-10 Soyuz TM-13 Soyuz TM-28 Anatoli Berezovoi Karol Bobko Nikolai Budarin Soyuz T-5 STS 6, STS 51D, STS 51J STS 71, Soyuz TM-27 Valeri Bykovsky Kenneth Cameron Robert Cenker Vostok 5, Soyuz 22, Soyuz 31 STS 37, STS 56, STS 74 STS 61C Roger Crouch Samuel Durrance Reinhold Ewald STS 83, STS 94 STS 35, STS 67 Soyuz TM-25 John Fabian Mohammed Faris Bertalan Farkas STS 7, STS 51G Soyuz TM-3 Soyuz 36 Anatoli Filipchenko Dirk Frimout Owen Garriott Soyuz 7, Soyuz 16 STS 45 Skylab III, STS 9 Viktor Gorbatko Georgi Grechko Alexei Gubarev Soyuz 7, Soyuz 24, Soyuz 37 Soyuz 17, Soyuz 26 Soyuz 17, Soyuz 28 Soyuz T-14 Jugderdemidyn Gurragchaa Henry Hartsfield, Jr. Terence Henricks Soyuz 39 STS 4, STS 41D, STS 61A STS 44, STS 55, STS 70 STS 78 Miroslaw Hermaszewski Richard Hieb Millie Hughes-Fulford Soyuz 30 STS 39, STS 49, STS 65 STS 40 Alexander Ivanchenkov Georgi Ivanov Sigmund Jahn Soyuz 29, Soyuz T-6 Soyuz 33 Soyuz 31 Alexander Kaleri Valeri Korzun Valeri Kubasov Soyuz TM-14, Soyuz TM-26 Soyuz TM-24 Soyuz 6, Apollo-Soyuz Soyuz 36 Alexander Lazutkin Alexei Leonov Byron Lichtenberg Soyuz TM-25 Voskhod 2, Apollo-Soyuz STS 9, STS 45 Vladimir Lyakhov Oleg Makarov Musa Manarov Soyuz 32, Soyuz T-9 Soyuz 12, Soyuz 27, Soyuz T-3 Soyuz TM-4, Soyuz TM-11 Soyuz TM-6 Jon McBride Ulf Merbold Ernst Messerschmid STS 41G -

Human-Machine Issues in the Soviet Space Program1

CHAPTER 4 HUMAN-MACHINE ISSUES IN THE SOVIET SPACE PROGRAM1 Slava Gerovitch n December 1968, Lieutenant General Nikolai Kamanin, the Deputy Chief Iof the Air Force’s General Staff in charge of cosmonaut selection and training, wrote an article for the Red Star, the Soviet Armed Forces newspaper, about the forthcoming launch of Apollo 8. He entitled his article “Unjustified Risk” and said all the right things that Soviet propaganda norms prescribed in this case. But he also kept a private diary. In that diary, he confessed what he could not say in an open publication.“Why do the Americans attempt a circumlunar flight before we do?” he asked. Part of his private answer was that Soviet spacecraft designers “over-automated” their spacecraft and relegated the cosmonaut to the role of a monitor, if not a mere passenger. The attempts to create a fully automatic control system for the Soyuz spacecraft, he believed, critically delayed its development. “We have fallen behind the United States for two or three years,” he wrote in the diary.“We could have been first on the Moon.”2 Kamanin’scriticism wassharedbymanyinthe cosmonautcorps who describedthe Soviet approach to thedivisionoffunctionbetween humanand machineas“thedominationofautomata.”3 Yet among the spacecraft designers, 1. I wish to thank David Mindell, whose work on human-machine issues in the U.S. space program provided an important reference point for my own study of a parallel Soviet story. Many ideas for this paper emerged out of discussions with David in the course of our collaboration on a project on the history of the Apollo Guidance Computer between 2001 and 2003, and later during our work on a joint paper for the 2004 annual meeting of the Society for the History of Technology in Amsterdam. -

Russia May Bring Forward Manned Launch After Rocket Failure 12 October 2018

Russia may bring forward manned launch after rocket failure 12 October 2018 The next Soyuz launch had been scheduled to take a new three-person crew to the ISS on December 20 and a Progress cargo ship had been set to blast off on October 31. Leaving ISS unmanned? Veteran cosmonaut Krikalyov said that "in theory" the ISS could remain unmanned but added Russia would do "everything possible not to let this happen." Credit: CC0 Public Domain A space walk planned for mid-November has also been cancelled, he said. The crew had planned to examine a hole in a Russian spacecraft docked at the orbiting station. Russia said Friday it was likely to bring forward the flight of a new manned space mission to the Thursday's aborted launch took place in the International Space Station but postpone the presence of NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine launch of a cargo ship after a rocket failure that who was visiting Russia and Baikonur this week. forced two crew members to make an emergency landing. The incident was a huge embarrassment for Moscow, which has recently touted plans to send It was the first such incident in Russia's post-Soviet cosmonauts to the Moon and Mars. history—an unprecedented setback for the country's space industry. All manned launches have been suspended and a criminal probe has been launched. Russian cosmonaut Aleksey Ovchinin and US astronaut Nick Hague sped back to Earth when the The Kremlin said experts were working to Soyuz rocket failed shortly after launching from determine what caused the rocket failure. -

![Association of Space Explorers Collection [Schweickart] NASM](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6342/association-of-space-explorers-collection-schweickart-nasm-2276342.webp)

Association of Space Explorers Collection [Schweickart] NASM

As ronaut cosmo /autDi INTRODUCTION May /985 Over the past four years, a period in US-USSR relations that the New York Times characterized as hitting an "all time low," a number of individuals who share a unique perspective of the Earth, have been meeting informally, shaping possibilities for cooperation and communication of an unprecedented nature. Having seen Earth from a vantage point that blurs political differences, several former American Astronauts and Soviet Cosmonauts have, in the spirit of the historic Apollo-Soyuz linkup in space, continued to explore terrestrial connections that could lead to exchanging their common experiences and solutions to global issues of mutual concern. Now a decade after that memorable hand-shake in space, the first Planetary Congress of Space Explorers will take place October 2-7, 1985, near Paris, to be attended not only by Soviets and Americans, but by representatives from other nations as members of a growing community of people who have orbited the Earth. The potential for this group of individuals to influence the consciousness of our time is perhaps unique in the history of explorers. The goal of this Initiative is to create a forum; the content and direction this forum might take will arise out of the special experience and perspective of the Astronauts and Cosmonauts themselves. The following report offers (1) a brief survey of events leading to the establishment of The Association of Space Explorers, (2) a summary of the planning meeting held during September, 1984, in France, and (3) text of the joint public statement. We are grateful to be able to include photographs of the meeting by Victoria Elliot, who accompanied the US Delegation. -

President Nazarbayev Calls for Further Integration and International

+21° / +13°C WEDNESDAY, JUNE 29, 2016 No 12 (102) www.astanatimes.com SCO Presidents Urge Cooperation in Transit, In Historic Win, Kazakhstan Infrastructure, Counter-Terrorism Elected for UN Security Council for 2017-2018 By Galiaskar Seitzhan NEW YORK – After a gruelling six-year campaign, which took its leaders and diplomats and intro- duced Kazakhstan to far flung cor- ners of the world, from Europe to the Pacific Islands, from Africa to Latin America, Kazakhstan won the right to sit on the United Nations Security Nameplate for Kazakhstan at the UN Council in 2017-2018. General Assembly hall is seen on June In the second round of voting by 28 during the vote count. the UN General Assembly here on these priorities in the main body of June 28, Kazakhstan was elected multilateral diplomacy in the world, from the Asian-Pacific group, re- ceiving 138 votes, which is more Kazakhstan intends to closely co- than two thirds of the UN member operate with all partners without states needed for the win. exception, members in the Security For the first time Kazakhstan has Council and the UN as a whole, the declared his candidacy for non-per- country’s diplomats have said ear- lier. Presidents of the six member states of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation - China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan - are joined manent members of the UN Security for a group photo by the leaders of Afghanistan, Belarus, India, Mongolia, Pakistan, and Turkmenistan as well as the foreign minister of Iran and representatives of Council in June 2010. Since then, As a non-permanent UN Security numerous international organisations who are SCO observers and partners for dialogue. -

Ore Drammatiche Negli Scali Italiani

l'Unit& / domenica 30 settembre 1973 PAG. 5 / cronache Conclusa la nuova impresa spaziale sovietica Da settimane malafi, infermieri e medici lottano contro le tremende condizioni nell'ospedale La Soyuz puntuale e tornataa terra: S'indigna il direttore del Cotugno per tutto bene a bordo le verita denunciate anche dal Times Effettuata tutta una serie di collaudi - Strumentazione perfetta - In buona forma Vassili Lazarev e Oleg Makarov La batteriologa inglese ha ripetuto il grido d'allarme lanciato un mese fa sul nostro giornale da un «semplice» camionista «fuggito» dal nosocomio — «Sono scappato per lavarmi e cambiarmi...» — I sanitari che si rifiutarono di lasciare i reparti per ribadire la necessita di un'organizzazione piu adeguata alle circostanze — I deboli argomenti del primario che minaccia quereie — La sopportabile «normalita» Rispedita a casa poi s'e saputo che aveva il colera Dal nostro corrispondente TARANTO. 29 Accade anche questo: la donna di 42 anni, F.T. era nella sua casa di via Pisanelli con i suoi sci figli ed il marito quando e stato accertato che era affetta da colera. La signora era stata dimessa giovedl 27 alle ore 17, alcune ore dopo cioe che i risultati delle analisi comunicate ai sanitari dell'ospedale Santissima Annunziata erano stati dichiarati negativi. Erano — quando questa comunicazione vetiiva effettuata da parte del laboratorio di igiene e pro- filassi — le 11,45. Alle 19 U'l'altra comunicazione smentiva il precedente verdetto dichiarando posilivi gli esami: F.T. di 42 anni aveva il colera, ma intanto era stata riportata in seno alia famiglia. Non appena i sanitari dell'ospedale f-ono venuti a conoscenza del nuovo risultato emerso dagli esami di laboratorio eseguiti nell'Istituto di Igiene di Bari.