THE CANADIAN ARMY TROPHY Achieving Excellence in Tank Gunnery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unclassified U.S

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Navy Master at Arms 1st Class Ekali Brooks (R) coordinates with a U.S. Soldier to provide security while he and his dog Bak search for explosives in nearby classrooms, Sep. 10, 2008. Iraqi soldiers and U.S. Troops from 2nd Squadron, 14th Cavalry Regiment, and Bravo Company, 52nd Anti-Tank Regiment, 25th Infantry Division conducted a cooperative medical engagement at a local elementary school in Hor Al Bosh, Iraq, to provide medical treatment to the local Iraqi people. (U.S. Army photo by Spc. Daniel Herrera/Released) 080910-A-8725H-220 UNCLASSIFIED An Iraqi soldier interacts with local children, Sep. 10, 2008. Iraqi soldiers and U.S. Troops from 2nd Squadron, 14th Cavalry Regiment, and Bravo Company, 52nd Anti-Tank Regiment, 25th Infantry Division, conducted a cooperative medical engagement at a local elementary school in Hor Al Bosh, Iraq, to provide medical treatment to the local Iraqi people. (U.S. Army photo by Spc. Daniel Herrera/Released) 080910-A-8725H-502 UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Army Sgt. Susan McGuyer, 2nd Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 25th Infantry Division, searches Iraqi women before they can be treated by medical personnel, Sep. 10, 2008. Iraqi soldiers and U.S. Troops from 2nd Squadron, 14th Cavalry Regiment, and Bravo Company, 52nd Anti-Tank Regiment, 25th Infantry Division conducted a cooperative medical engagement at a local elementary school in Hor Al Bosh, Iraq, to provide medical treatment to the local Iraqi people. (U.S. Army photo by Spc. Daniel Herrera/Released) 080910-A-8725H-335 UNCLASSIFIED Iraqi soldiers conduct a cooperative medical engagement at a local elementary school in Hor Al Bosh, Iraq, Sep. -

Clearance of Depleted Uranium (DU) Hazards

Technical notes for mine action Technical Note 09.30/ 02 Version 3.0 TNMA 1st February 2015 Clearance of Depleted Uranium (DU) hazards i Technical Note 09.30-02/15 Version 3.0 (1st February 2015) Warning This document is distributed for use by the mine action community, review and comment. Although in a similar format to the International Mine Action Standards (IMAS) it is not part of the IMAS Series. It is subject to change without notice and may not be referred to as an International Mine Action Standard. Recipients of this document are invited to submit, with their comments, notification of any relevant patent rights of which they are aware and to provide supporting documentation. Comments should be sent to [email protected] with a copy to [email protected]. The content of this document has been drawn from open source information and has been technically validated as far as reasonably possible. Users should be aware of this limitation when utilising the information contained within this document. They should always remember that this is only an advisory document: it is not an authoritative directive. ii Technical Note 09.30-02/15 Version 3.0 (1st February 2015) Contents Contents ........................................................................................................................................ iii Foreword ....................................................................................................................................... iv Introduction.................................................................................................................................... -

October 2015

RUN FOR THE WALL Quarterly Newsletter “We Ride For Those Who Can’t” October 2015 NOTE: Run For The Wall and RFTW are trademarks of Run For The Wall, Inc. The use of Run For The Wall and RFTW is strictly prohibited without the expressed written permission of the Board of Directors of Run For The Wall, Inc. In This Issue: The Editor’s Notes Post-9/11 GI Bill President’s Message New Agent Orange Study 2016 Central Route Coordinator Full Honors for MOH Veteran After 94 Years 2016 Combat Hero Bike Build Angel Fire Reunion Grand Lake Fundraiser for RFTW Kerrville Reunion The Army’s Spectacular Hidden Treasure Pending Legislation Room Bringing Them Home The Story of the Vietnam Wall Sick Call Life in the Navy Taps Mind-Body Treatment for PTSD Closing Thoughts Camp Lejeune Study Released ________________________________________________________________________________________ THE EDITOR’S NOTES About a year ago I talked about the new Veterans Court that had been started up in Lake Havasu City. Veterans Courts were at that time very new, and few people were even aware that such a thing existed. Our Veterans Court has been running for almost two years now, and I am well-entrenched in the Veterans Resource Team that helps find resources for veterans going through Veterans Court system. Representatives from all of our local veterans organizations are on the team, as well as several dozen service agencies, including our local Interagency, the VA, the Vet Center, the Veterans Resource Center, and many more agencies that are instrumental in providing the help that veterans need so that they can once again become good members of society. -

Progress in Delivering the British Army's Armoured

AVF0014 Written evidence submitted by Nicholas Drummond “Progress in Delivering the British Army’s Armoured Vehicle Capability.” Nicholas Drummond Defence Industry Consultant and Commentator Aura Consulting Ltd. ______________________________________________________________________________ _________ Contents Section 1 - Introduction Section 2 - HCDC questions 1. Does the Army have a clear understanding of how it will employ its armoured vehicles in future operations? 2. Given the delays to its programmes, will the Army be able to field the Strike Brigades and an armoured division as envisaged by the 2015 SDSR? 3. How much has the Army spent on procuring armoured vehicles over the last 20 years? How many vehicles has it procured with this funding? 4. What other capabilities has the Army sacrificed in order to fund overruns in its core armoured vehicles programmes? 5. How flexible can the Army be in adapting its current armoured vehicle plans to the results of the Integrated Review? 6. By 2025 will the Army be able to match the potential threat posed by peer adversaries? 7. Is the Army still confident that the Warrior CSP can deliver an effective vehicle capability for the foreseeable future? 8. To what extent does poor contractor performance explain the delays to the Warrior and Ajax programmes? 9. Should the UK have a land vehicles industrial strategy, and if so what benefits would this bring? 10. What sovereign capability for the design and production of armoured vehicles does the UK retain? 11. Does it make sense to upgrade the Challenger 2 when newer, more capable vehicles may be available from our NATO allies? 12. What other key gaps are emerging within the Army’s armoured vehicle capability? 13. -

List of Exhibits at IWM Duxford

List of exhibits at IWM Duxford Aircraft Airco/de Havilland DH9 (AS; IWM) de Havilland DH 82A Tiger Moth (Ex; Spectrum Leisure Airspeed Ambassador 2 (EX; DAS) Ltd/Classic Wings) Airspeed AS40 Oxford Mk 1 (AS; IWM) de Havilland DH 82A Tiger Moth (AS; IWM) Avro 683 Lancaster Mk X (AS; IWM) de Havilland DH 100 Vampire TII (BoB; IWM) Avro 698 Vulcan B2 (AS; IWM) Douglas Dakota C-47A (AAM; IWM) Avro Anson Mk 1 (AS; IWM) English Electric Canberra B2 (AS; IWM) Avro Canada CF-100 Mk 4B (AS; IWM) English Electric Lightning Mk I (AS; IWM) Avro Shackleton Mk 3 (EX; IWM) Fairchild A-10A Thunderbolt II ‘Warthog’ (AAM; USAF) Avro York C1 (AS; DAS) Fairchild Bolingbroke IVT (Bristol Blenheim) (A&S; Propshop BAC 167 Strikemaster Mk 80A (CiA; IWM) Ltd/ARC) BAC TSR-2 (AS; IWM) Fairey Firefly Mk I (FA; ARC) BAe Harrier GR3 (AS; IWM) Fairey Gannet ECM6 (AS4) (A&S; IWM) Beech D17S Staggerwing (FA; Patina Ltd/TFC) Fairey Swordfish Mk III (AS; IWM) Bell UH-1H (AAM; IWM) FMA IA-58A Pucará (Pucara) (CiA; IWM) Boeing B-17G Fortress (CiA; IWM) Focke Achgelis Fa-330 (A&S; IWM) Boeing B-17G Fortress Sally B (FA) (Ex; B-17 Preservation General Dynamics F-111E (AAM; USAF Museum) Ltd)* General Dynamics F-111F (cockpit capsule) (AAM; IWM) Boeing B-29A Superfortress (AAM; United States Navy) Gloster Javelin FAW9 (BoB; IWM) Boeing B-52D Stratofortress (AAM; IWM) Gloster Meteor F8 (BoB; IWM) BoeingStearman PT-17 Kaydet (AAM; IWM) Grumman F6F-5 Hellcat (FA; Patina Ltd/TFC) Branson/Lindstrand Balloon Capsule (Virgin Atlantic Flyer Grumman F8F-2P Bearcat (FA; Patina Ltd/TFC) -

Modern Application of Mechanized-Cavalry Groups for Cavalry Echelons Above Brigade by MAJ Joseph J

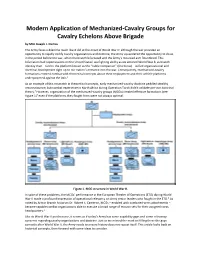

Modern Application of Mechanized-Cavalry Groups for Cavalry Echelons Above Brigade by MAJ Joseph J. Dumas The Army faces a dilemma much like it did at the onset of World War II: although the war provided an opportunity to rapidly codify cavalry organizations and doctrine, the Army squandered the opportunity to do so in the period before the war, when the branch bifurcated and the Army’s mounted arm floundered. This bifurcation had repercussions on the United States’ warfighting ability as we entered World War II, as branch identity then – tied to the platform known as the “noble companion” (the horse) – stifled organizational and doctrinal development right up to our nation’s entrance into the war. Consequently, mechanized-cavalry formations entered combat with theoretical concepts about their employment and their vehicle platforms underpowered against the Axis.1 As an example of this mismatch in theoretical concepts, early mechanized-cavalry doctrine peddled stealthy reconnaissance, but combat experience in North Africa during Operation Torch didn’t validate pre-war doctrinal theory.2 However, organization of the mechanized-cavalry groups (MCGs) created effective formations (see Figure 1)3 even if the platforms they fought from were not always optimal. Figure 1. MCG structure in World War II. In spite of these problems, the MCGs’ performance in the European Theater of Operations (ETO) during World War II made a profound impression of operational relevancy on Army senior leaders who fought in the ETO.4 As noted by Armor Branch historian Dr. Robert S. Cameron, MCGs – enabled with combined-arms attachments – became capable combat organizations able to execute a broad range of mission sets for their assigned corps headquarters.5 Like its World War II predecessor, it seems as if today’s Army has some capability gaps and some relevancy concerns regarding cavalry organizations and doctrine. -

A Volunteer from America.Pdf

1 2 A Volunteer From America By Bob Mack 1ST Signal Brigade Nha Trang, Republic of Vietnam 1967 – 1968 3 Dedicated to those that served ©2010 by Robert J. McKendrick All Rights Reserved 4 In-Country The big DC-8 banked sharply into the sun and began its descent toward the Cam Ranh peninsula, the angle of drop steeper than usual in order to frustrate enemy gunners lurking in the nearby mountains. Below, the impossibly blue South China Sea seemed crusted with diamonds. I had spent the last two months at home, thanks to a friendly personnel sergeant in Germany who’d cut my travel 5 orders to include a 60-day “delay en route” before I was due to report in at Ft. Lewis, Washington for transportation to the 22 nd Replacement Battalion, MACV (Military Assistance Command Vietnam). Now I was twenty-five hours out from Seattle, and on the verge of experiencing the Vietnam War at first hand. It was the fifth of July 1967. Vietnam stunk. Literally. After the unbelievable heat, the smell was the first thing you noticed, dank and moldy, like a basement that had repeatedly flooded and only partially dried. Or like a crypt… The staff sergeant was a character straight out of Central Casting, half full of deep South gruffness and Dixie grizzle, the other half full of shit. He paced back and forth while we stood in formation in the hot sand. “Welcome to II Corps, Republic of Vet-nam,” he said. Then he gave us the finger. “Take a good look at it, boys. -

1St Infantry Division Post Template

1A HOME OF THE BIG RED ONE THE 1ST INFANTRY DIVISION POST 1DivPost.com FRIDAY, MAY 1, 2015 Vol. 7, No. 18 FORT RILEY, KAN. Discussion Training Staff Sgt. Jerry Griffis | 1ST INF. DIV. Soldiers of 1st Infantry Division Sustainment Brigade change their unit patches to the “Big Red One” patch April 22 at Cav- alry Parade Field on Fort Riley, Kansas. The changing of the patches was part of an inactivation/activation ceremony and the 1st Infantry Division Sustainment Brigade also uncased new colors for the ceremony. ‘Durable’ Soldiers join Corey Schaadt | 1ST INF. DIV. Gen. David G. Perkins, commander of the United States Army Training and Doctrine Command, leads a training discussion with platoon leaders and platoon sergeants April 20 at Fort Riley. The subject of the lecture was the development of the Army division in wearing Operating Concept. General explains Army Operating ‘Big Red One’ patch By J. Parker Roberts the McCormick Foundation, whose 1ST INF. DIV. PUBLIC AFFAIRS role in part is to sustain the legacy of Concept to ‘Big Red One’ leaders the Big Red One “and that patch you It was a sound like no other as hun- just put on your shoulders,” Wesley dreds of “Durable” Soldiers removed told the Durable Soldiers in forma- By J. Parker Roberts their left arm patches in unison, re- tion on the field. 1ST INF. DIV. PUBLIC AFFAIRS placing them with the “Big Red One” The 1st Sust. Bde. was originally patch worn by their fellow Soldiers formed as Division Trains in 1917 On post to tour Fort Riley across the 1st Infantry Division. -

ARMOR Janfeb2007 Covers.Indd

The Professional Bulletin of the Armor Branch PB 17-07-1 Editor in Chief Features LTC SHANE E. LEE 7 Not Quite Counterinsurgency: A Cautionary Tale for U.S. Forces Based on Israel’s Operation Change of Direction Managing Editor by Captain Daniel Helmer CHRISTY BOURGEOIS 12 Lebanon 2006: Did Merkava Challenge Its Match? by Lieutenant Colonel David Eshel, IDF, Retired Commandant 15 Teaching and Learning Counterinsurgency MG ROBERT M. WILLIAMS at the Armor Captains Career Course by Major John Grantz and Lieutenant Colonel John Nagl 18 The Challenge of Leadership ARMOR (ISSN 0004-2420) is published bi- during the Conduct of Counterinsurgency Operations month ly by the U.S. Army Armor Center, by Major Jon Dunn ATTN: ATZK-DAS-A, Building 1109A, 201 6th Avenue, Ste 373, Fort Knox, KY 40121-5721. 20 Building for the Future: Combined Arms Offi cers by Captain Chad Foster Disclaimer: The information contained in AR- MOR represents the professional opinions of 23 The Battalion Chaplain: A Combat Multiplier the authors and does not necessarily reflect by Chaplain (Captain) David Fell the official Army or TRADOC position, nor does it change or supersede any information 26 Practical Lessons from the Philippine Insurrection presented in other official Army publications. by Lieutenant Colonel Jayson A. Altieri, Lieutenant Commander John A. Cardillo, and Major William M. Stowe III Official distribution is limited to one copy for each armored brigade headquarters, ar mored 35 Integrating Cultural Sensitivity into Combat Operations cavalry regiment headquarters, armor battal- by Major Mark S. Leslie ion headquarters, armored cavalry squadron 39 Advice from a Former Military Transition Team Advisor head quarters, reconnaissance squadron head- by Major Jeff Weinhofer quar ters, armored cavalry troop, armor com- pany, and motorized brigade headquarters of 42 Arab Culture and History: Understanding is the First Key to Success the United States Army. -

Dispatches Vol

Dagwood Dispatches Vol. 30-No. 2 April 2020 Issue No. 103 NEWSLETTER OF THE 16th INFANTRY REGIMENT ASSOCIATION Mission: To provide a venue for past and present members of the 16th Infantry Regiment to share in the history and well-earned camaraderie of the US Army’s greatest regiment. News from the Front The 16th Infantry Regiment Association is a Commemorative Partner with the Department of Defense Commemoration of the 50th Anniversary of the Vietnam War Annual membership fees ($30.00) WEre due 1 January 2020. 50 Years Ago . 1-16 IN departs FSB Dakota for Fort Riley No Mission Too Difficult No Sacrifice Too Great Duty First! Governing Board Other Board Officers Association Staff President Board Emeritii Quartermaster Steven E. Clay LTG (R) Ronald L. Watts Bill Prine 307 North Broadway Robert B. Humphries (918) 398-3493 Leavenworth, KS 66048 Woody Goldberg [email protected] (913) 651-6857 [email protected] Honorary Colonel of the Regiment DD Editorial Staff First Vice President Ralph L. Kauzlarich Steve Clay, Editor Bob Hahn 210 Manor Lane (913) 651-6857 St. Johns, FL 32259 11169 Lake Chapel Lane [email protected] (904) 310-2729 Reston, VA 20191-4719 [email protected] (202) 360-7885 Vietnam-Cold War Recruiter [email protected] Honorary Sergeant Major Dee Daugherty (804) 731-5631 Second Vice President Thomas Pendleton [email protected] Bob Humphries 1708 Kingwood Drive 1734 Ellenwood Drive Manhattan, KS 66502 Desert Storm-GWOT Recruiter Roswell, GA 30075 (785) 537-6213 Dan Alix (770) 993-8312 [email protected] (706) 573-6510 [email protected] [email protected] Adjutant Commander, 1st Battalion Erik Anthes LTC Matthew R. -

Cobra Strike! a Reality

By Spc. Jason Dangel, 4th BCT PAO, 4th Inf. Div. of operations with their ISF counterparts. The 4th Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division, Cobra combat support and combat service support units, "Cobras," deployed in late November 2005 in support of the 4th Special Troops Battalion and 704th Support Operation Iraqi Freedom and officially assumed responsibil- Battalion were responsible for command and control for all ity of battle space in central and southern Baghdad from the the units of Task Force Cobra, while simultaneously provid- 4th Brigade Combat Team, 3rd Infantry Division, Jan. 14, ing logistical support for the brigade's Soldiers. 2006. The 3rd Battalion, 67th Armor was attached to the 4th After a successful transition with the 3rd Inf. Div.'s Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division and operat- "Vanguard" Brigade, the Cobra Brigade was ready for its ed from FOB Rustamiyah, located in the northern portion of first mission in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. the Iraqi capital. As the Ivy Division's newest brigade combat team, the The Cobra Brigade oversaw the security of many key events Cobra Brigade, comprised of approximately 5,000 combat- to include the first session of the Iraqi Council of ready Soldiers, was deployed to Forward Operating Base Representatives. Prosperity in Baghdad's International Zone and operated in The Iraqi Council of Representatives, the parliament some of the most dangerous neighborhoods in Baghdad, to elected under the nation's new constitution, convened at the include Al-Doura, Al-Amerriyah, Abu T'schir, Al-Ademiyah Parliament Center in central Baghdad where 275 representa- and Gazaliyah. -

Brazilian Tanks British Tanks Canadian Tanks Chinese Tanks

Tanks TANKS Brazilian Tanks British Tanks Canadian Tanks Chinese Tanks Croatian Tanks Czech Tanks Egyptian Tanks French Tanks German Tanks Indian Tanks Iranian Tanks Iraqi Tanks Israeli Tanks Italian Tanks Japanese Tanks Jordanian Tanks North Korean Tanks Pakistani Tanks Polish Tanks Romanian Tanks Russian Tanks Slovakian Tanks South African Tanks South Korean Tanks Spanish Tanks Swedish Tanks Swiss Tanks Ukrainian Tanks US Tanks file:///E/My%20Webs/tanks/tanks_2.html[3/22/2020 3:58:21 PM] Tanks Yugoslavian Tanks file:///E/My%20Webs/tanks/tanks_2.html[3/22/2020 3:58:21 PM] Brazilian Tanks EE-T1 Osorio Notes: In 1982, Engesa began the development of the EE-T1 main battle tank, and by 1985, it was ready for the world marketplace. The Engesa EE-T1 Osorio was a surprising development for Brazil – a tank that, while not in the class of the latest tanks of the time, one that was far above the league of the typical third-world offerings. In design, it was similar to many tanks of the time; this was not surprising, since Engesa had a lot of help from West German, British and French armor experts. The EE-T1 was very promising – an excellent design that several countries were very interested in. The Saudis in particular went as far as to place a pre- order of 318 for the Osorio. That deal, however, was essentially killed when the Saudis saw the incredible performance of the M-1 Abrams and the British Challenger, and they literally cancelled the Osorio order at the last moment. This resulted in the cancellation of demonstrations to other countries, the demise of Engesa, and with it a promising medium tank.