Cacao Use and the San Lorenzo Olmec

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert M. Rosenswig

FAMSI © 2004: Robert M. Rosenswig El Proyecto Formativo Soconusco Traducido del Inglés por Alex Lomónaco Año de Investigación: 2002 Cultura: Olmeca Cronología: Pre-Clásico Ubicación: Soconusco, Chiapas, México Sitio: Cuauhtémoc Tabla de Contenidos Introducción El Proyecto Formativo Soconusco 2002 Análisis en curso Conclusion Lista de Figuras Referencias Citadas Entregado el 6 de septiembre del 2002 por: Robert M. Rosenswig Department of Anthropology Yale University [email protected] Introducción El sitio de Cuauhtémoc está ubicado dentro de una zona del Soconusco que no ha sido documentada con anterioridad y que se encuentra entre las organizaciones estatales del Formativo Temprano de Mazatlán (Clark y Blake 1994), el centro del Formativo Medio de La Blanca (Love 1993) y el centro del Formativo Tardío de Izapa (Lowe et al. 1982) (Figura 1). Aprovechando la refinada cronología del Soconusco (Cuadro 1), el trabajo de campo que se describe a continuación aporta datos que permiten rastrear el desarrollo de Cuauhtémoc durante los primeros 900 años de vida de asentamiento en Mesoamérica. Este período de tiempo está dividido en siete fases cerámicas, y de esta forma, permite que se rastreen, prácticamente siglo por siglo, los cambios ocurridos en todas las clases de cultura material. Estos datos están siendo utilizados para documentar el surgimiento y el desarrollo de las complejidades sociopolíticas en el área. Además de los procesos locales, el objetivo de esta investigación es determinar la naturaleza de las relaciones cambiantes entre las élites de la Costa del Golfo de México y el Soconusco. El trabajo también apunta a ser significativo en lo que respecta a cruzamientos culturales, dado que Mesoamérica es sólo una entre un puñado de áreas del mundo donde la complejidad sociopolítica surgió independientemente, y el Soconusco contiene algunas de las sociedades más tempranas en las que esto ocurrió (Clark y Blake 1994; Rosenswig 2000). -

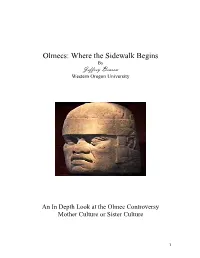

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History 2005 Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Benson, Jeffrey, "Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins" (2005). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 126. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/126 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins By Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University An In Depth Look at the Olmec Controversy Mother Culture or Sister Culture 1 The discovery of the Olmecs has caused archeologists, scientists, historians and scholars from various fields to reevaluate the research of the Olmecs on account of the highly discussed and argued areas of debate that surround the people known as the Olmecs. Given that the Olmecs have only been studied in a more thorough manner for only about a half a century, today we have been able to study this group with more overall gathered information of Mesoamerica and we have been able to take a more technological approach to studying the Olmecs. The studies of the Olmecs reveals much information about who these people were, what kind of a civilization they had, but more importantly the studies reveal a linkage between the Olmecs as a mother culture to later established civilizations including the Mayas, Teotihuacan and other various city- states of Mesoamerica. -

La Blanca Is a Preclassic Archaeological Site Located on The

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE DIFFERENTIAL ACCESS TO RESOURCES AND THE EMERGING ELITE: OBSIDIAN AT LA BLANCA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology, Public Archaeology By Laura E. Hoffman December 2012 Signature Page The thesis of Laura E. Hoffman is approved: ________________________________ ____________ Cathy L. Costin, Ph.D. Date ________________________________ ____________ Matthew Des Lauriers, Ph.D. Date ________________________________ ____________ Michael W. Love, Ph.D., Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Acknowledgements This thesis would never have been completed were it not for many, many people who have helped me along the way. I extend my sincere gratitude to everyone who has inspired, encouraged, assisted, and at times cajoled me along this journey: Michael W. Love, Cathy Costin, Matt DesLauriers, The California State University, Northridge Anthropology Department, Hector Neff, The Institute for Integrated Research in Materials, Environments, and Society, Terry Joslin, Kelli Brasket, John Dietler, Benny Vargas, Cara Corsetti, Cheryle Hunt, Clarus Backes, Mom, Dad, Andrea, Norville, and Brad Harris. Without your continued encouragement and understanding I would not have been able to complete this thesis. iii Table of Contents Signature Page .................................................................................................................... ii Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................... -

Ancient Civilizations of Mesoamerica: a Reader, M

Archaeology of Mesoamerica George Washington University Course Anth 3814.10 Spring, 2013 Dr. J. Blomster e-mail: [email protected], phone, ext. 44880 Class Meets: Tues & Thur, 3:45 – 5:00, HAH, Rm. 202 Office Hours: Thursday, 11:00-1:00, HAH Rm. 303 The cultural region referred to as Mesoamerica – encompassing modern day Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador – was the cradle of early and spectacular civilizations in the New World. This course will apply an anthropological perspective to the rich cultural traditions of Mesoamerica, focusing on the unique character of Mesoamerican civilization and its contributions to the world. No prerequisites are required. The structure of the course follows the chronological sequence of Mesoamerican cultures. After examining the peopling of the New World and the initial hunting/gathering lifestyle, the focus is on the development of agriculture, pottery, and the first permanent villages. We will examine the replacement of egalitarian societies by complex chiefdoms, states and even empires. Emphasis will be placed on the development of Mesoamerica’s first civilization – the Olmec – and the features first synthesized by the Olmecs that resonate in subsequent Mesoamerican civilizations. Different approaches to complex society and political organization will be examined by comparing the cities and states of Teotihuacán, Monte Albán, and various Maya polities. After examining the militarism that arose after the demise of these major states, the course will conclude with a brief examination -

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins by Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins By Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University An In Depth Look at the Olmec Controversy Mother Culture or Sister Culture 1 The discovery of the Olmecs has caused archeologists, scientists, historians and scholars from various fields to reevaluate the research of the Olmecs on account of the highly discussed and argued areas of debate that surround the people known as the Olmecs. Given that the Olmecs have only been studied in a more thorough manner for only about a half a century, today we have been able to study this group with more overall gathered information of Mesoamerica and we have been able to take a more technological approach to studying the Olmecs. The studies of the Olmecs reveals much information about who these people were, what kind of a civilization they had, but more importantly the studies reveal a linkage between the Olmecs as a mother culture to later established civilizations including the Mayas, Teotihuacan and other various city- states of Mesoamerica. The data collected links the Olmecs to other cultures in several areas such as writing, pottery and art. With this new found data two main theories have evolved. The first is that the Olmecs were the mother culture. This theory states that writing, the calendar and types of art originated under Olmec rule and later were spread to future generational tribes of Mesoamerica. The second main theory proposes that the Olmecs were one of many contemporary cultures all which acted sister cultures. The thought is that it was not the Olmecs who were the first to introduce writing or the calendar to Mesoamerica but that various indigenous surrounding tribes influenced and helped establish forms of writing, a calendar system and common types of art. -

Cacao Use and the San Lorenzo Olmec

Cacao use and the San Lorenzo Olmec Terry G. Powisa,1, Ann Cyphersb, Nilesh W. Gaikwadc,d, Louis Grivettic, and Kong Cheonge aDepartment of Geography and Anthropology, Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, GA 30144; bInstituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico 04510; cDepartment of Nutrition and dDepartment of Environmental Toxicology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616; and eDepartment of Anthropology, Trent University, Peterborough, ON, Canada K9J 7B8 Edited by Michael D. Coe, Yale University, New Haven, CT, and approved April 8, 2011 (received for review January 12, 2011) Mesoamerican peoples had a long history of cacao use—spanning Selection of San Lorenzo and Loma del Zapote Pottery Samples. The more than 34 centuries—as confirmed by previous identification present study included analysis of 156 pottery sherds and vessels of cacao residues on archaeological pottery from Paso de la Amada obtained from stratified deposits excavated under the aegis of on the Pacific Coast and the Olmec site of El Manatí on the Gulf the San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán Archaeological Project (SLTAP). Coast. Until now, comparable evidence from San Lorenzo, the pre- Items selected represented Early Preclassic occupation contexts mier Olmec capital, was lacking. The present study of theobromine at two major Olmec sites, San Lorenzo (n = 154) and Loma del residues confirms the continuous presence and use of cacao prod- Zapote (n = 2), located in the lower Coatzacoalcos drainage ucts at San Lorenzo between 1800 and 1000 BCE, and documents basin of southern Veracruz State, Mexico (Fig. 1). Sample se- assorted vessels forms used in its preparation and consumption. -

Open NEJ Dissertation.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School OBSIDIAN EXCHANGE AND PIONEER FARMING IN THE FORMATIVE PERIOD TEOTIHUACAN VALLEY A Dissertation in Anthropology by Nadia E. Johnson ©2020 Nadia E. Johnson Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2020 The dissertation of Nadia E. Johnson was reviewed and approved by the following: Kenneth G. Hirth Professor of Anthropology Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee José Capriles Assistant Professor of Anthropology Kirk French Associate Teaching Professor of Anthropology Larry Gorenflo Professor of Landscape Architecture, Eleanor P. Stuckeman Chair in Design Timothy Ryan Program Head and Professor of Anthropology ii ABSTRACT: The Formative Period marked a period of rapid social change and population growth in the Central Highlands of Mexico, culminating in the emergence of the Teotihuacan state in the Terminal Formative. This dissertation explores several aspects of economic life among the people who occupied the Teotihuacan Valley prior to the development of the state, focusing on the Early and Middle Formative Periods (ca. 1500 – 500 B.C.) as seen from Altica (1200 – 850 B.C.), the earliest known site in the Teotihuacan Valley. Early Formative populations in the Teotihuacan Valley, and northern Basin of Mexico more broadly, were sparse during this period, likely because it is cool, arid climate was less agriculturally hospitable than the southern basin. Altica was located in an especially agriculturally marginal section of the Teotihuacan Valley’s piedmont. While this location is suboptimal for subsistence agriculturalists, Altica’s proximity to the economically important Otumba obsidian source suggests that other economic factors influenced settlement choice. -

Redalyc.Los Orígenes Del Privilegio En El Soconusco, 1650 Ac

Revista Pueblos y Fronteras Digital ISSN: 1870-4115 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México México Clark, John E.; Pye, Mary E. Los orígenes del privilegio en el soconusco, 1650 a.c.: dos décadas de investigación Revista Pueblos y Fronteras Digital, núm. 2, 2006, p. 0 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Distrito Federal, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=90600208 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Revista Pueblos y Fronteras digital Año 2006, número 2 Historia y Antropología del deporte http://www.pueblosyfronteras.unam.mx MISCELÁNEA LOS ORÍGENES DEL PRIVILEGIO EN EL SOCONUSCO , 1650 A.C.: DOS DÉCADAS DE INVESTIGACIÓN John E. Clark y Mary E. Pye NEW WORLD ARCHAEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION En este trabajo presentamos los resultados más sobresalientes de las investigaciones arqueológicas practicadas desde 1985 en el Soconusco, Chiapas, México (figura 1), particularmente en la zona de Mazatán. Hemos investigado los orígenes de la desigualdad social en esta región, un tema complejo que implica varias preguntas secundarias concernientes a la herencia del privilegio a lo largo del tiempo. Aunque nuestras investigaciones de campo empezaron como parte de los estudios doctorales de Clark (1994), han incluido a muchas personas y proyectos de investigación desde el principio, especialmente a Michael Blake y sus estudiantes. Con el tiempo los cuestionamientos originales han sido modificados a la luz de nuevos datos. -

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Chocolate Is a Typically

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Chocolate is a typically sweet, usually brown food preparation of Theobroma cacao seeds, a Greek word that means "food of the gods”. Cacao has been cultivated by many cultures for at least three millennia in Mesoamerica. The earliest evidence of use traces to the Mokaya (Mexico and Guatemala), with evidence of chocolate beverages dating back to 1900 BC. In fact, the majority of Mesoamerican people made chocolate beverages, including the Maya and Aztecs, who made it into a beverage known as xocolātl Nahuatl, a Nahuatl word meaning "bitter water". The seeds of the cacao tree have an intense bitter taste and must be fermented to develop the flavor. (Anonymous, 2017) The cacao tree is an evergreen found in over 50 tropical countries, and estimated to be grown by 2 million to 2.5 million producers, the tree can grow up to 30 feet but is often pruned to make harvesting easier for the farmers. Once a tree is planted, it can take up to five years before it produces cacao pods, and it can continue to produce pods year round until it is 25 or 30 years old. Once the pods are ripe, the farmer harvest the pods then graded for quality and placed into piles. The pods are then opened with a machete or a wooden club by cracking the pod so that it can be split in half so they can take the cocoa beans. Cocoa beans then fermented up to 6 days then dried bringing the humidity of the beans down to between 6% and 8%. -

Soconusco Formative Project

FAMSI © 2002: Robert M. Rosenswig Soconusco Formative Project Research Year: 2002 Culture: Olmec Chronology: Pre-Classic Location: Soconusco, Chiapas, México Site: Cuauhtémoc Table of Contents Introduction Soconusco Formative Project 2002 Analysis in Progress Conclusion List of Figures Sources Cited Submitted 09/16/2002 by: Robert M. Rosenswig Department of Anthropology Yale University [email protected] Introduction The Cuauhtémoc site is located within a previously undocumented zone of the Soconusco between the Early Formative Mazatán polities (Clark and Blake 1994), the Middle Formative center of La Blanca (Love 1993) and the Late Formative center of Izapa (Lowe et al. 1982) (see Figure 1). Taking advantage of the refined Soconuscan chronology (Table 1), the fieldwork described below provides data to track developments at Cuauhtémoc over the first 900 years of settled life in Mesoamerica. This time period is divided into seven ceramic phases, and so, allows for changes in all classes of material culture to be tracked on almost a century-by-century basis. These data are being used to document the emergence and development of sociopolitical complexity in the area. In addition to local processes, the goal of this research is to determine the nature of changing relations between elites on the Gulf Coast of México and the Soconusco. The work also aims to be significant cross-culturally as Mesoamerica is one of only a handful of areas in the world where sociopolitical complexity emerged independently and the Soconusco contains some -

The Avocado (Persea Americana, Lauraceae) Crop in Mesoamerica: 10,000 Years of History

THE AVOCADO (PERSEA AMERICANA, LAURACEAE) CROP IN MESOAMERICA: 10,000 YEARS OF HISTORY MARÍA ELENA GALINDO-TOVAR,1,5 AMAURY M.ARZATE-FERNÁNDEZ,2 NISAO OGATA-AGUILAR,3 AND IVONNE LANDERO-TORRES4 Abstract. The most ancient evidence of the existence of the avocado tree (Persea americana, Lauraceae) in Mesoamerica is about 10,000 years ago in Coaxcatlan, Puebla (Mexico). Since then, the history of the avocado has been preserved and recorded in Mesoamerica, the domestication center for the species, and in northern South America, where pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican cultures dispersed it. In colonial times, the Spanish valued the avo- cado fruit highly and documented it in numerous texts. Since then, the avocado tree has been introduced into places where the climate is appropriate for its cultivation. Avocado is now the fourth most important tropical fruit in the world, and Mexico is the main producer, with more than one million metric tons produced in 2005. Resumen. La evidencia más antigua de la presencia del aguacate (Persea americana, Lauraceae) en Mesoamérica es de hace 10,000 años, en Coaxcatlán, Puebla (México). Desde entonces, la historia del aguacate ha sido documentada en Mesoamérica, su centro de domesticación, y en el norte de Sudamérica, en donde fue dispersado por las culturas que habitaron en Mesoamérica en la época pre-Hispánica. En el tiempo de la Colonia, los españoles apreciaron esta fruta y la documentaron en numerosos textos. Desde entonces el aguacate ha sido introducido en los lugares donde el clima es apropiado para su desarrollo. Actualmente el aguacate es la cuarta fruta tropical más importante en el mundo y México es el principal productor con más de un millón de toneladas métricas producidas en el año 2005. -

Mesoamerica Re-Explored a Symposium In

Jaguars, Eagles & Feathered Serpents: Dr. Michael D. Coe is Charles J. McCurdy Professor of Anthropology, Emeritus, Yale University. His research interests focus Mesoamerica Re-explored on the pre-Spanish civilizations of Mesoamerica, especially the Olmec and Maya; and on the Khmer civilization of Cambodia. He has A Symposium in Homage to also conducted archaeological excavations on forts of the French and Indian War in Massachusetts. Among his 20 published books are Dr. Michael D. Coe Mexico (1962, with 4 subsequent editions, two co-authored with Rex Koontz); The Maya (1966, with 7 subsequent editions); The Maya Scribe and His World (1973); Lords of the Underworld (1978); In the Land of the Olmec (1980, with Richard A. Diehl); Breaking the Maya Code (1992); The True History of Chocolate (1996, with Sophie D. Coe); The Art of the Maya Scribe (1997, with Justin Kerr); Reading the Maya Glyphs (2001, with Mark Van Stone); Angkor and the Khmer Civilization (2003); Final Report: An Archaeologist Excavates His Past (2006); The Line of Forts, Historical Archaeology on the Frontier of Massachusetts (2006). His newest book is Royal Cities of the Ancient Maya, (2012, with photographer Barry Brukoff). He has been a member of the National Academy of Sciences since 1986. He has been given the Tatiana Proskouriakoff Award by Harvard University (1989); the James D. Burke Prize in Fine Arts, Saint Louis Art Museum (2001); the Order of the Quetzal, Government of Guatemala (2004); the Orden del Pop, Museo Popol Vuh (2006); and the Linda Schele Award, University of Texas (2008). On April 13, 2013 he will be presented the Tlamatini Award by the Art History Society in conjunction with the Department of Art History at CSULA.