Cantón Corralito: Objects from a Possible Gulf Olmec Colony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Food, Feathers, and Offerings: Early Formative Period Bird Exploitation at Paso de la Amada, Mexico Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5d09k6pk Author Bishop, Katelyn Jo Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Food, Feathers, and Offerings: Early Formative Period Bird Exploitation at Paso de la Amada, Mexico A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Anthropology by Katelyn Jo Bishop 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Food, Feathers, and Offerings: Early Formative Period Bird Exploitation at Paso de la Amada, Mexico by Katelyn Jo Bishop Master of Arts in Anthropology University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Richard G. Lesure, Chair Bird remains from archaeological sites have the potential to inform research on many aspects of prehistoric life. In Mesoamerica, they were a food source, as well as a source of feathers and bone. But they were also components of ritual performance, dedicatory offerings, subjects of iconographic representation, characters in myth, and even deities. Their significance is demonstrated ethnographically, ethnohistorically, and archaeologically. This thesis addresses the role of birds at an Early Formative period ceremonial center on the Pacific coast of Chiapas, Mexico. The avian faunal assemblage from the site of Paso de la Amada was analyzed in order to understand how the exploitation and use of birds articulated with the establishment of hereditary inequality at Paso de la Amada and its emergence as a ceremonial center. Results indicate that birds were exploited as a food source as well as for their feathers and bone, and that they played a particularly strong role in ritual performance. -

Robert M. Rosenswig

FAMSI © 2004: Robert M. Rosenswig El Proyecto Formativo Soconusco Traducido del Inglés por Alex Lomónaco Año de Investigación: 2002 Cultura: Olmeca Cronología: Pre-Clásico Ubicación: Soconusco, Chiapas, México Sitio: Cuauhtémoc Tabla de Contenidos Introducción El Proyecto Formativo Soconusco 2002 Análisis en curso Conclusion Lista de Figuras Referencias Citadas Entregado el 6 de septiembre del 2002 por: Robert M. Rosenswig Department of Anthropology Yale University [email protected] Introducción El sitio de Cuauhtémoc está ubicado dentro de una zona del Soconusco que no ha sido documentada con anterioridad y que se encuentra entre las organizaciones estatales del Formativo Temprano de Mazatlán (Clark y Blake 1994), el centro del Formativo Medio de La Blanca (Love 1993) y el centro del Formativo Tardío de Izapa (Lowe et al. 1982) (Figura 1). Aprovechando la refinada cronología del Soconusco (Cuadro 1), el trabajo de campo que se describe a continuación aporta datos que permiten rastrear el desarrollo de Cuauhtémoc durante los primeros 900 años de vida de asentamiento en Mesoamérica. Este período de tiempo está dividido en siete fases cerámicas, y de esta forma, permite que se rastreen, prácticamente siglo por siglo, los cambios ocurridos en todas las clases de cultura material. Estos datos están siendo utilizados para documentar el surgimiento y el desarrollo de las complejidades sociopolíticas en el área. Además de los procesos locales, el objetivo de esta investigación es determinar la naturaleza de las relaciones cambiantes entre las élites de la Costa del Golfo de México y el Soconusco. El trabajo también apunta a ser significativo en lo que respecta a cruzamientos culturales, dado que Mesoamérica es sólo una entre un puñado de áreas del mundo donde la complejidad sociopolítica surgió independientemente, y el Soconusco contiene algunas de las sociedades más tempranas en las que esto ocurrió (Clark y Blake 1994; Rosenswig 2000). -

Cacao Use and the San Lorenzo Olmec

Cacao use and the San Lorenzo Olmec Terry G. Powisa,1, Ann Cyphersb, Nilesh W. Gaikwadc,d, Louis Grivettic, and Kong Cheonge aDepartment of Geography and Anthropology, Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, GA 30144; bInstituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico 04510; cDepartment of Nutrition and dDepartment of Environmental Toxicology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616; and eDepartment of Anthropology, Trent University, Peterborough, ON, Canada K9J 7B8 Edited by Michael D. Coe, Yale University, New Haven, CT, and approved April 8, 2011 (received for review January 12, 2011) Mesoamerican peoples had a long history of cacao use—spanning Selection of San Lorenzo and Loma del Zapote Pottery Samples. The more than 34 centuries—as confirmed by previous identification present study included analysis of 156 pottery sherds and vessels of cacao residues on archaeological pottery from Paso de la Amada obtained from stratified deposits excavated under the aegis of on the Pacific Coast and the Olmec site of El Manatí on the Gulf the San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán Archaeological Project (SLTAP). Coast. Until now, comparable evidence from San Lorenzo, the pre- Items selected represented Early Preclassic occupation contexts mier Olmec capital, was lacking. The present study of theobromine at two major Olmec sites, San Lorenzo (n = 154) and Loma del residues confirms the continuous presence and use of cacao prod- Zapote (n = 2), located in the lower Coatzacoalcos drainage ucts at San Lorenzo between 1800 and 1000 BCE, and documents basin of southern Veracruz State, Mexico (Fig. 1). Sample se- assorted vessels forms used in its preparation and consumption. -

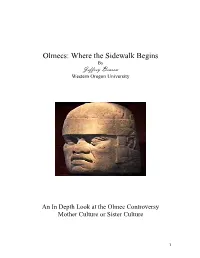

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History 2005 Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Benson, Jeffrey, "Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins" (2005). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 126. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/126 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins By Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University An In Depth Look at the Olmec Controversy Mother Culture or Sister Culture 1 The discovery of the Olmecs has caused archeologists, scientists, historians and scholars from various fields to reevaluate the research of the Olmecs on account of the highly discussed and argued areas of debate that surround the people known as the Olmecs. Given that the Olmecs have only been studied in a more thorough manner for only about a half a century, today we have been able to study this group with more overall gathered information of Mesoamerica and we have been able to take a more technological approach to studying the Olmecs. The studies of the Olmecs reveals much information about who these people were, what kind of a civilization they had, but more importantly the studies reveal a linkage between the Olmecs as a mother culture to later established civilizations including the Mayas, Teotihuacan and other various city- states of Mesoamerica. -

Formative Mexican Chiefdoms and the Myth of the "Mother Culture"

Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 19, 1–37 (2000) doi:10.1006/jaar.1999.0359, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on Formative Mexican Chiefdoms and the Myth of the “Mother Culture” Kent V. Flannery and Joyce Marcus Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1079 Most scholars agree that the urban states of Classic Mexico developed from Formative chiefdoms which preceded them. They disagree over whether that development (1) took place over the whole area from the Basin of Mexico to Chiapas, or (2) emanated entirely from one unique culture on the Gulf Coast. Recently Diehl and Coe (1996) put forth 11 assertions in defense of the second scenario, which assumes an Olmec “Mother Culture.” This paper disputes those assertions. It suggests that a model for rapid evolution, originally presented by biologist Sewall Wright, provides a better explanation for the explosive development of For- mative Mexican society. © 2000 Academic Press INTRODUCTION to be civilized. Five decades of subsequent excavation have shown the situation to be On occasion, archaeologists revive ideas more complex than that, but old ideas die so anachronistic as to have been declared hard. dead. The most recent attempt came when In “Olmec Archaeology” (hereafter ab- Richard Diehl and Michael Coe (1996) breviated OA), Diehl and Coe (1996:11) parted the icy lips of the Olmec “Mother propose that there are two contrasting Culture” and gave it mouth-to-mouth re- “schools of thought” on the relationship 1 suscitation. between the Olmec and the rest of Me- The notion that the Olmec of the Gulf soamerica. -

La Blanca Is a Preclassic Archaeological Site Located on The

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE DIFFERENTIAL ACCESS TO RESOURCES AND THE EMERGING ELITE: OBSIDIAN AT LA BLANCA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology, Public Archaeology By Laura E. Hoffman December 2012 Signature Page The thesis of Laura E. Hoffman is approved: ________________________________ ____________ Cathy L. Costin, Ph.D. Date ________________________________ ____________ Matthew Des Lauriers, Ph.D. Date ________________________________ ____________ Michael W. Love, Ph.D., Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Acknowledgements This thesis would never have been completed were it not for many, many people who have helped me along the way. I extend my sincere gratitude to everyone who has inspired, encouraged, assisted, and at times cajoled me along this journey: Michael W. Love, Cathy Costin, Matt DesLauriers, The California State University, Northridge Anthropology Department, Hector Neff, The Institute for Integrated Research in Materials, Environments, and Society, Terry Joslin, Kelli Brasket, John Dietler, Benny Vargas, Cara Corsetti, Cheryle Hunt, Clarus Backes, Mom, Dad, Andrea, Norville, and Brad Harris. Without your continued encouragement and understanding I would not have been able to complete this thesis. iii Table of Contents Signature Page .................................................................................................................... ii Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................... -

Ancient Civilizations of Mesoamerica: a Reader, M

Archaeology of Mesoamerica George Washington University Course Anth 3814.10 Spring, 2013 Dr. J. Blomster e-mail: [email protected], phone, ext. 44880 Class Meets: Tues & Thur, 3:45 – 5:00, HAH, Rm. 202 Office Hours: Thursday, 11:00-1:00, HAH Rm. 303 The cultural region referred to as Mesoamerica – encompassing modern day Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador – was the cradle of early and spectacular civilizations in the New World. This course will apply an anthropological perspective to the rich cultural traditions of Mesoamerica, focusing on the unique character of Mesoamerican civilization and its contributions to the world. No prerequisites are required. The structure of the course follows the chronological sequence of Mesoamerican cultures. After examining the peopling of the New World and the initial hunting/gathering lifestyle, the focus is on the development of agriculture, pottery, and the first permanent villages. We will examine the replacement of egalitarian societies by complex chiefdoms, states and even empires. Emphasis will be placed on the development of Mesoamerica’s first civilization – the Olmec – and the features first synthesized by the Olmecs that resonate in subsequent Mesoamerican civilizations. Different approaches to complex society and political organization will be examined by comparing the cities and states of Teotihuacán, Monte Albán, and various Maya polities. After examining the militarism that arose after the demise of these major states, the course will conclude with a brief examination -

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins by Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins By Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University An In Depth Look at the Olmec Controversy Mother Culture or Sister Culture 1 The discovery of the Olmecs has caused archeologists, scientists, historians and scholars from various fields to reevaluate the research of the Olmecs on account of the highly discussed and argued areas of debate that surround the people known as the Olmecs. Given that the Olmecs have only been studied in a more thorough manner for only about a half a century, today we have been able to study this group with more overall gathered information of Mesoamerica and we have been able to take a more technological approach to studying the Olmecs. The studies of the Olmecs reveals much information about who these people were, what kind of a civilization they had, but more importantly the studies reveal a linkage between the Olmecs as a mother culture to later established civilizations including the Mayas, Teotihuacan and other various city- states of Mesoamerica. The data collected links the Olmecs to other cultures in several areas such as writing, pottery and art. With this new found data two main theories have evolved. The first is that the Olmecs were the mother culture. This theory states that writing, the calendar and types of art originated under Olmec rule and later were spread to future generational tribes of Mesoamerica. The second main theory proposes that the Olmecs were one of many contemporary cultures all which acted sister cultures. The thought is that it was not the Olmecs who were the first to introduce writing or the calendar to Mesoamerica but that various indigenous surrounding tribes influenced and helped establish forms of writing, a calendar system and common types of art. -

Mesoamerican Ballcourt

Mesoamerican ballgame The Mesoamerican ballgame or Ōllamaliztli Nahuatl pronunciation: [oːlːamaˈlistɬi] in Nahuatl was a sport with ritual associations played since 1,400 B.C.[1] by the pre-Columbian peoples of Ancient Mexico and Central America. The sport had different versions in different places during the millennia, and a newer more modern version of the game, ulama, is still played in a few places by the indigenous population.[2] The rules of Ōllamaliztli are not known, but judging from its descendant, ulama, they were probably similar to racquetball,[3] where the aim is to keep the ball in play. The stone ballcourt goals (see photo to right) are a late addition to the game. In the most widespread version of the game, the players struck the ball with their hips, although some versions allowed the use of forearms, rackets, bats, or handstones. The ball was made of solid rubber and weighed as much as 4 kg (9 lbs), and sizes differed greatly over time or according to the version played. The game had important ritual aspects, and major formal ballgames were held as ritual events, often featuring human sacrifice. The sport was also played casually for recreation by children and perhaps even women.[4] Pre-Columbian ballcourts have been found throughout Mesoamerica, as far south as Nicaragua, and possibly as far north as what is now the U.S. state of Arizona.[5] These ballcourts vary considerably in size, but all have long narrow alleys with side-walls against which the balls could bounce. Origins Map showing sites where early ballcourts, -

Cacao Use and the San Lorenzo Olmec

Cacao use and the San Lorenzo Olmec Terry G. Powisa,1, Ann Cyphersb, Nilesh W. Gaikwadc,d, Louis Grivettic, and Kong Cheonge aDepartment of Geography and Anthropology, Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, GA 30144; bInstituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico 04510; cDepartment of Nutrition and dDepartment of Environmental Toxicology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616; and eDepartment of Anthropology, Trent University, Peterborough, ON, Canada K9J 7B8 Edited by Michael D. Coe, Yale University, New Haven, CT, and approved April 8, 2011 (received for review January 12, 2011) Mesoamerican peoples had a long history of cacao use—spanning Selection of San Lorenzo and Loma del Zapote Pottery Samples. The more than 34 centuries—as confirmed by previous identification present study included analysis of 156 pottery sherds and vessels of cacao residues on archaeological pottery from Paso de la Amada obtained from stratified deposits excavated under the aegis of on the Pacific Coast and the Olmec site of El Manatí on the Gulf the San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán Archaeological Project (SLTAP). Coast. Until now, comparable evidence from San Lorenzo, the pre- Items selected represented Early Preclassic occupation contexts mier Olmec capital, was lacking. The present study of theobromine at two major Olmec sites, San Lorenzo (n = 154) and Loma del residues confirms the continuous presence and use of cacao prod- Zapote (n = 2), located in the lower Coatzacoalcos drainage ucts at San Lorenzo between 1800 and 1000 BCE, and documents basin of southern Veracruz State, Mexico (Fig. 1). Sample se- assorted vessels forms used in its preparation and consumption. -

Open NEJ Dissertation.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School OBSIDIAN EXCHANGE AND PIONEER FARMING IN THE FORMATIVE PERIOD TEOTIHUACAN VALLEY A Dissertation in Anthropology by Nadia E. Johnson ©2020 Nadia E. Johnson Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2020 The dissertation of Nadia E. Johnson was reviewed and approved by the following: Kenneth G. Hirth Professor of Anthropology Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee José Capriles Assistant Professor of Anthropology Kirk French Associate Teaching Professor of Anthropology Larry Gorenflo Professor of Landscape Architecture, Eleanor P. Stuckeman Chair in Design Timothy Ryan Program Head and Professor of Anthropology ii ABSTRACT: The Formative Period marked a period of rapid social change and population growth in the Central Highlands of Mexico, culminating in the emergence of the Teotihuacan state in the Terminal Formative. This dissertation explores several aspects of economic life among the people who occupied the Teotihuacan Valley prior to the development of the state, focusing on the Early and Middle Formative Periods (ca. 1500 – 500 B.C.) as seen from Altica (1200 – 850 B.C.), the earliest known site in the Teotihuacan Valley. Early Formative populations in the Teotihuacan Valley, and northern Basin of Mexico more broadly, were sparse during this period, likely because it is cool, arid climate was less agriculturally hospitable than the southern basin. Altica was located in an especially agriculturally marginal section of the Teotihuacan Valley’s piedmont. While this location is suboptimal for subsistence agriculturalists, Altica’s proximity to the economically important Otumba obsidian source suggests that other economic factors influenced settlement choice. -

'Juego De Pelota' Mesoamericano

Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y del Deporte / International Journal of Medicine and Science of Physical Activity and Sport ISSN: 1577-0354 [email protected] Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Rodríguez-López, J.; Vicente-Pedraz,España M.; Mañas-Bastida, A . CULTURA DE PASO DE LA AMADA, CREADOR A DEL ‘JUEGO DE PELOTA’ MESOAMERICANO Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y del Deporte / International Journal of Medicine and Science of Physical Activity and Sport, vol. 16, núm. 61, marzo, 2016, pp. 69-83 Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Madrid, España Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=54244745006 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Rev.int.med.cienc.act.fís.deporte - vol. 16 - número 61 - ISSN: 1577-0354 Rodríguez-López, J.; Vicente-Pedraz, M. y Mañas-Bastida, A. (2016) Cultura de paso de la amada, creadora del ‘juego de pelota’ mesoamericano / Culture of paso de la amada, creator of ‘mesoamerican ballgame’. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y el Deporte vol. 16 (61) pp. 69-83. Http://cdeporte.rediris.es/revista/revista61/artcultura670.htm DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15366/rimcafd2016.61.006 ORIGINAL CULTURA DE PASO DE LA AMADA, CREADORA DEL ‘JUEGO DE PELOTA’ MESOAMERICANO CULTURE OF PASO DE LA AMADA, CREATOR OF ‘MESOAMERICAN BALLGAME’ Rodríguez-López, J.1; Vicente-Pedraz, M.2 y Mañas-Bastida, A.3 1 Profesor Titular, Doctor en Medicina, Departamento de Educación Física y Deportiva, Facultad de Ciencias del Deporte, Universidad de Granada, España.