Soconusco Formative Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TUXTLA GUTIÉRREZ L Platanal Ío

L E L E L EL E EL L E L E E L EL E E L L E E L E L E L L L E L L E E L E E L L E 1 E 0 0 0 L E L EL L E L E E L E E L E L L L E L E E E L L 1 L 5 E 0 0 E EL L E L L L L E E E E E E L L L L L E E !( !( E L L E !( L E L E E L E L L L E E L L E E E EL L !( EL !( L E E L E L L E L E L !( L E EL E E !( L L E E E L E E L L L L E L L E !( L E )" E E E !( L L E L E L !( L E E E L L !( E L E E L L !( EL E # L L L E !( E E C.H. E L L L L E E E E L L E L L L E !( # L !( L E Bombaná !( E E E E L !( L ©! !( E !( !( L L !( E E !( L L !( L E L E # L E !( L E E E L !( E L E L E !( !(!( L E L EL L E EL !( E !( EL L L L E E E L E E E L L L L E E !( L E L L E L E E L !( # # L E E L L L L E !( L E E !( E L E L L E L !( EL E L E E L E E E EL L L !( E L L E L E O E L E E Ï L E EL L L E L E L E L L La EL o S E L !( E y o ' E !( E L ro m !( L L L E EL EL Ar b E L L r E a E ©! E E L L L 1 !( EL L L 5 E E EL C.H. -

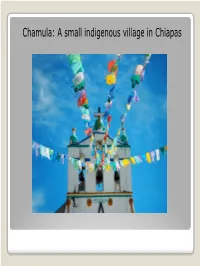

Chamula: a Small Indigenous Village in Chiapas

Chamula: A small indigenous village in Chiapas StateState ofof Chiapas,Chiapas, MexicoMexico ChamulaChamula This is a community of Pre-Hispanic origin whose name means "Thick "Water." The Chamulas have always been fiercely independent: they resisted the Spanish upon their arrival in 1524 and later staged a famous rebellion in 1869, attacking the nearby colonial settlement of San Cristobal. San Juan Chamula is the principal town, being the main religious and economic center of the community. The Chamulas enjoy being a closed community. Like other indigenous communities in this region, they can be identified by their clothes: in this case distinctive purple and pink colors predominate. This Tzotzil community is considered one of most important of its kind, not only by sheer numbers of population, but by customs practices here, as well. Information taken from www.luxuriousmexico.com This is the house of someone who migrated to the States to work and returned to build a house styled like those he saw in the United States. In the distance is the town square with This picture was taken in front the cathedral. of the cathedral. Sheep are considered sacred by the Chamula. Thus, they are not killed but allowed to graze and used for their wool. How do you think this happened historically? TheThe SundaySunday MarketMarket GirlGirl withwith HuipilHuipil SyncretismSyncretism Religious syncretism is the blending of two belief systems Religious syncretism often takes place when foreign beliefs are introduced to an indigenous belief system and the teachings are blended For the indigenous peoples of Mexico, Catholic beliefs blended with their native The above picture shows the religious beliefs traditional offerings from a Mayan Syncretism allowed the festival with a picture of Jesus, a native peoples to continue central figure in the Christian religion. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Food, Feathers, and Offerings: Early Formative Period Bird Exploitation at Paso de la Amada, Mexico Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5d09k6pk Author Bishop, Katelyn Jo Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Food, Feathers, and Offerings: Early Formative Period Bird Exploitation at Paso de la Amada, Mexico A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Anthropology by Katelyn Jo Bishop 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Food, Feathers, and Offerings: Early Formative Period Bird Exploitation at Paso de la Amada, Mexico by Katelyn Jo Bishop Master of Arts in Anthropology University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Richard G. Lesure, Chair Bird remains from archaeological sites have the potential to inform research on many aspects of prehistoric life. In Mesoamerica, they were a food source, as well as a source of feathers and bone. But they were also components of ritual performance, dedicatory offerings, subjects of iconographic representation, characters in myth, and even deities. Their significance is demonstrated ethnographically, ethnohistorically, and archaeologically. This thesis addresses the role of birds at an Early Formative period ceremonial center on the Pacific coast of Chiapas, Mexico. The avian faunal assemblage from the site of Paso de la Amada was analyzed in order to understand how the exploitation and use of birds articulated with the establishment of hereditary inequality at Paso de la Amada and its emergence as a ceremonial center. Results indicate that birds were exploited as a food source as well as for their feathers and bone, and that they played a particularly strong role in ritual performance. -

Macromycetes of the San José Educational Park, Municipality Of

http://doi.org/10.15174/au.2019.2127 Macromycetes of the San José educational park, municipality of Zinacantan, Chiapas, Mexico Macromicetos del parque educativo San José, municipio de Zinacantán, Chiapas, México Freddy Chanona-Gómez1, Peggy Elizabeth Alvarez Gutiérrez2*, Yolanda del Carmen Pérez-Luna3 1Departamento de Vigilancia Sanitaria. Laboratorio Estatal de Salud Pública. 2Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (Conacyt)-Tecnológico Nacional de México-Instituto Tecnológico de Tuxtla Gutiérrez. Carretera Panamericana km 1080 Col. Juan Crispín, 29050. Tuxtla Gutiérrez Chapas. Correo electrónico: [email protected]; [email protected] 3Ingeniería Agroindustrial. Universidad Politécnica de Chiapas. *Corresponding author. Abstract Chiapas is one of the most biodiverse regions of our Planet; however, the knowledge of tropical mushrooms in this state is limited. As a consequence of this lack of information of the mycobiota of Chiapas and areas such as San José (SJ) park, it is very important to carry out inventories of biotic resources as a basic and fundamental research tool for some protected areas, in order to develop studies for conservation. This study aims to prepare a list of the macrofungi species in the SJ park. Specimens were collected along five consecutive years, and 148 species (21 Ascomycetes and 126 Basidiomycetes) were identified. The most common substrate was humus (110 species, 74.82%). Forty-six species that can be used for human consumption were found. Thus, the mycological value for the study area was 31.29%. Also, 27 new records for Chiapas (5 Ascomycotina and 22 Basidiomycotina) were found. Keywords: Macrofungal diversity; tropical mushrooms; mycological stock; ascomycotina; Basidiomycotina. Resumen Chiapas es una de las regiones más biodiversas del Planeta; sin embargo, el conocimiento de los hongos de las regiones tropicales es limitado, en particular, de la microbiota de Chiapas y en el parque educativo San José. -

Región Iii – Mezcalapa

REGIÓN III – MEZCALAPA Territorio La región socioeconómica III Mezcalapa, según el Marco Geoestadístico 2010 que publica el INEGI, tiene una superficie de 2,654.95 km2 y se integra por 9 municipios localizados en la parte noroeste del estado. Colinda al norte con el estado de Tabasco y con la Región VIII Norte, al este con la Región VII De los bosques, al sur con la Región II Valles Zoque y al oeste con el estado de Oaxaca La cabecera regional es la ciudad es Copainalá. SUPERFICIE SUPERFICIE CABECERAS MUNICIPALES MUNICIPIO (% (km2) REGIONAL) NOMBRE ALTITUD Chicoasén 115.24 4.34 Chicoasén 251 Coapilla 154.89 5.83 Coapilla 1,617 Copainalá 346.14 13.04 Copainalá 450 Francisco León 209.93 7.91 Rivera el Viejo Carmen 827 Mezcalapa 847.31 31.91 Raudales Malpaso 136 Ocotepec 61.09 2.30 Ocotepec 1,436 Osumacinta 92.22 3.47 Osumacinta 388 San Fernando 359.26 13.53 San Fernando 912 Tecpatán 468.87 17.66 Tecpatán 318 TOTAL 2,654.95 Nota: la altitud de las cabeceras municipales está expresada en metros sobre el nivel del mar. Se ubica dentro de las provincias fisiográficas que se reconocen como Montañas del Norte y Altos de Chiapas. Dentro de las dos provincias fisiográficas de la región se reconocen cuatro formas del relieve sobre las cuales se apoya la descripción del medio físico y cultural del territorio regional. En la zona norte, este y oeste de la región predomina la sierra alta escarpada y compleja y la sierra alta de laderas tendidas; al sur de la región predomina la sierra alta de laderas tendidas, seguido de sierra alta escarpada y compleja y en menor proporción el cañón típico. -

Agroindustrias De Mapastepec Sa De Cv According to the Requirements of the Rspo Principles & Criteria

Doc. 2_3_3_En ANNOUNCEMENT OF PUBLIC CONSULTATION REGARDING THE INITIAL CERTIFICATION AUDIT OF - AGROINDUSTRIAS DE MAPASTEPEC SA DE CV ACCORDING TO THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE RSPO PRINCIPLES & CRITERIA Dear Sir or Madam, IBD Certificações informs that the company Agroindustrias de Mapastepec SA de CV (RSPO member n° 2- 0360-12-000-00) is now in the application process for RSPO Principles & Criteria Certification related to the production of sustainable palm oil production. The audit is scheduled to take place between March 08 of 2021 and March 12 of 2021. Agroindustrias de Mapastepec SA de CV Address Av. Lopez Mateos Norte. No. Ext. 391, No. Int Piso 21-A, Torre Bansi, Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico Contact person Jorge Coronel Phone / email +523336487800 / [email protected] Scope Production and sales of Palm Oil and Palm Kernel Products Palm Oil and Palm Kernel Standards that will be used for this assessment Mexican National Interpretation Of The Rspo Principles And Criteria For The Production Of Sustainable Palm Oil 2018 Mill Estimated / Forecast GPS references Palm Oil Mill’s Name Address capacity annual production (Mt) Latitude Longitude (Ton/hr) CSPO CSPK Planta Extractora Calle Central S/N, 60 2000 400 15°20'42.3 92°51'53.9 Mapastepec Ejido Nicolás Bravo II, 4"N 4"O Mapastepec, Mexico Suppliers’ base GPS references Area summary (Ha) Annual estimated Name Address Planted area Latitude Longitude Total certified (mature + certified FFB area immature) production (Mt) Buenos Aires Mapastepec, Chiapas, 15°18'45.5 92°52'48.5 107,00 -

Robert M. Rosenswig

FAMSI © 2004: Robert M. Rosenswig El Proyecto Formativo Soconusco Traducido del Inglés por Alex Lomónaco Año de Investigación: 2002 Cultura: Olmeca Cronología: Pre-Clásico Ubicación: Soconusco, Chiapas, México Sitio: Cuauhtémoc Tabla de Contenidos Introducción El Proyecto Formativo Soconusco 2002 Análisis en curso Conclusion Lista de Figuras Referencias Citadas Entregado el 6 de septiembre del 2002 por: Robert M. Rosenswig Department of Anthropology Yale University [email protected] Introducción El sitio de Cuauhtémoc está ubicado dentro de una zona del Soconusco que no ha sido documentada con anterioridad y que se encuentra entre las organizaciones estatales del Formativo Temprano de Mazatlán (Clark y Blake 1994), el centro del Formativo Medio de La Blanca (Love 1993) y el centro del Formativo Tardío de Izapa (Lowe et al. 1982) (Figura 1). Aprovechando la refinada cronología del Soconusco (Cuadro 1), el trabajo de campo que se describe a continuación aporta datos que permiten rastrear el desarrollo de Cuauhtémoc durante los primeros 900 años de vida de asentamiento en Mesoamérica. Este período de tiempo está dividido en siete fases cerámicas, y de esta forma, permite que se rastreen, prácticamente siglo por siglo, los cambios ocurridos en todas las clases de cultura material. Estos datos están siendo utilizados para documentar el surgimiento y el desarrollo de las complejidades sociopolíticas en el área. Además de los procesos locales, el objetivo de esta investigación es determinar la naturaleza de las relaciones cambiantes entre las élites de la Costa del Golfo de México y el Soconusco. El trabajo también apunta a ser significativo en lo que respecta a cruzamientos culturales, dado que Mesoamérica es sólo una entre un puñado de áreas del mundo donde la complejidad sociopolítica surgió independientemente, y el Soconusco contiene algunas de las sociedades más tempranas en las que esto ocurrió (Clark y Blake 1994; Rosenswig 2000). -

Cacao Use and the San Lorenzo Olmec

Cacao use and the San Lorenzo Olmec Terry G. Powisa,1, Ann Cyphersb, Nilesh W. Gaikwadc,d, Louis Grivettic, and Kong Cheonge aDepartment of Geography and Anthropology, Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, GA 30144; bInstituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico 04510; cDepartment of Nutrition and dDepartment of Environmental Toxicology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616; and eDepartment of Anthropology, Trent University, Peterborough, ON, Canada K9J 7B8 Edited by Michael D. Coe, Yale University, New Haven, CT, and approved April 8, 2011 (received for review January 12, 2011) Mesoamerican peoples had a long history of cacao use—spanning Selection of San Lorenzo and Loma del Zapote Pottery Samples. The more than 34 centuries—as confirmed by previous identification present study included analysis of 156 pottery sherds and vessels of cacao residues on archaeological pottery from Paso de la Amada obtained from stratified deposits excavated under the aegis of on the Pacific Coast and the Olmec site of El Manatí on the Gulf the San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán Archaeological Project (SLTAP). Coast. Until now, comparable evidence from San Lorenzo, the pre- Items selected represented Early Preclassic occupation contexts mier Olmec capital, was lacking. The present study of theobromine at two major Olmec sites, San Lorenzo (n = 154) and Loma del residues confirms the continuous presence and use of cacao prod- Zapote (n = 2), located in the lower Coatzacoalcos drainage ucts at San Lorenzo between 1800 and 1000 BCE, and documents basin of southern Veracruz State, Mexico (Fig. 1). Sample se- assorted vessels forms used in its preparation and consumption. -

20-May-2010 1 OECD Conference, Paris, May 19Th 2010 Session 3

20-May-2010 OECD Conference, Paris, May 19th 2010 Session 3: Improving income support and redistribution Ian Walker – Lead Economist, Social Protection, LAC Region, The World Bank www.oecd.org/els/social/inequality/emergingeconomies Conceptual framework: anti poverty programs in the context of SP systems The use of targeted subsidies to complement limited contributory social insurance coverage Typology of programs and targeting approaches Targeting and poverty reduction outcomes Downsides and limitations: program quality differentiation, savings effects and labor market behavioral effects Future challenges: ◦ Strengthening work opportunities ◦ Incentivizing savings ◦ Strengthening safety nets and human capital development 1 20-May-2010 Social Protection Objectives CONSUMPTION POVERTY HUMAN CAPITAL SMOOTHING PREVENTION DEVELOPMENT FINANCING INSTRUMENTS INSTITUTIONS ARRANGEMENTS Savings/risk pooling Workers’ Governance contributions Transfers / Monitoring and redistribution Payroll taxes evaluation General revenues Active policies Public/private sector Earmarked taxes INDIVIDUALS’ FIRMS’ PROVIDERS’ PUBLIC BEHAVIOR BEHAVIOR BEHAVIOR SPENDING Formal / informal Formal / informal Service quality Fiscal Job search effort Job creation Service costs sustainability Retirement Job destruction Service Allocative efficiency Job switching coordination Coverage (active members / labor force) 0 to 25 25 to 50 50 to 75 75 to 100 2 20-May-2010 Worldwide Comparison of Social Assistance and Social Insurance Spending 13.2 14 12 10 8 8 SA 6 SI 3.1 3.8 -

Johns Hopkins University Department of History 301 Gilman Hall 3400 N. Charles St Baltimore, MD 21218 [email protected] 617-233-6057

CASEY MARINA LURTZ CURRICULUM VITAE Johns Hopkins University Department of History 301 Gilman Hall 3400 N. Charles St Baltimore, MD 21218 [email protected] 617-233-6057 PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 2017-present JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY, DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Assistant Professor 2015-2017 HARVARD ACADEMY FOR INTERNATIONAL & AREA STUDIES Academy Scholar 2014-2015 HARVARD BUSINESS SCHOOL Harvard-Newcomen Fellow in Business History EDUCATION 2014 UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Ph.D. with distinction, Latin American History Dissertation: “Exporting from Eden: Coffee, Migration, and the Development of the Soconusco, Mexico, 1867-1920” 2008 UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO MA, Latin American History 2007 HARVARD COLLEGE A.B. cum laude, History and Literature with high honors in field Latin American Studies Certificate, Citation in Spanish PUBLICATIONS BOOK From the Grounds Up: Building an Export Economy in Southern Mexico, 1867- 1920. Stanford University Press, April 2019. Honorable mention for the Latin American Studies Association Nineteenth Century Section best book prize. Reviewed in: The Americas (https://doi-org.proxy1.library.jhu.edu/10.1017/tam.2020.59) The Business History Review (https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007680520000112) Agricultural History (https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3098/ah.2020.094.2.301) The Journal of Interdisciplinary History (muse.jhu.edu/article/757222) Labor (https://doi-org.proxy1.library.jhu.edu/10.1215/15476715-8643780) Environmental History (https://doi.org/10.1093/envhis/emaa062) CASEY MARINA LURTZ 2 CURRICULUM VITAE Historia Agraria de América Latina (https://www.haal.cl/index.php/haal/article/view/84) H-Latam (https://networks.h-net.org/node/23910/reviews/6173217/lewis-lurtz- grounds-building-export-economy-southern-mexico) H-Environment (https://networks.h-net.org/node/19397/discussions/5811455/h- environment-roundtable-review-lurtz-grounds-building-export) PEER REVIEWED JOURNAL ARTICLES 2021 “Codifying Credit: Everyday Contracting and the Spread of the Civil Code in Nineteenth-Century Mexico,” Law & History Review, forthcoming. -

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History 2005 Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Benson, Jeffrey, "Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins" (2005). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 126. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/126 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins By Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University An In Depth Look at the Olmec Controversy Mother Culture or Sister Culture 1 The discovery of the Olmecs has caused archeologists, scientists, historians and scholars from various fields to reevaluate the research of the Olmecs on account of the highly discussed and argued areas of debate that surround the people known as the Olmecs. Given that the Olmecs have only been studied in a more thorough manner for only about a half a century, today we have been able to study this group with more overall gathered information of Mesoamerica and we have been able to take a more technological approach to studying the Olmecs. The studies of the Olmecs reveals much information about who these people were, what kind of a civilization they had, but more importantly the studies reveal a linkage between the Olmecs as a mother culture to later established civilizations including the Mayas, Teotihuacan and other various city- states of Mesoamerica. -

Formative Mexican Chiefdoms and the Myth of the "Mother Culture"

Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 19, 1–37 (2000) doi:10.1006/jaar.1999.0359, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on Formative Mexican Chiefdoms and the Myth of the “Mother Culture” Kent V. Flannery and Joyce Marcus Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1079 Most scholars agree that the urban states of Classic Mexico developed from Formative chiefdoms which preceded them. They disagree over whether that development (1) took place over the whole area from the Basin of Mexico to Chiapas, or (2) emanated entirely from one unique culture on the Gulf Coast. Recently Diehl and Coe (1996) put forth 11 assertions in defense of the second scenario, which assumes an Olmec “Mother Culture.” This paper disputes those assertions. It suggests that a model for rapid evolution, originally presented by biologist Sewall Wright, provides a better explanation for the explosive development of For- mative Mexican society. © 2000 Academic Press INTRODUCTION to be civilized. Five decades of subsequent excavation have shown the situation to be On occasion, archaeologists revive ideas more complex than that, but old ideas die so anachronistic as to have been declared hard. dead. The most recent attempt came when In “Olmec Archaeology” (hereafter ab- Richard Diehl and Michael Coe (1996) breviated OA), Diehl and Coe (1996:11) parted the icy lips of the Olmec “Mother propose that there are two contrasting Culture” and gave it mouth-to-mouth re- “schools of thought” on the relationship 1 suscitation. between the Olmec and the rest of Me- The notion that the Olmec of the Gulf soamerica.