School Based Management Committees in Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unclaimed-Dividend202047.Pdf

UNCLAIMED DIVIDENDS 1 (HRH OBA) GABRIEL OLATERU ADEWOYE 140 ABDULLAHI AHMED 279 ABIGAL ODUNAYO LUCAS 418 ABOSEDE ADETUTU ORESANYA 2 (NZE) SUNDAY PAUL EZIEFULA 141 ABDULLAHI ALIU ADAMU 280 ABIGALIE OKUNWA OKAFOR 419 ABOSEDE AFOLAKEMI IBIDAPO-OBE 3 A A J ENIOLA 142 ABDULLAHI AYINLA ABDULRAZAQ 281 ABIJO AYODEJI ADEKUNLE 420 ABOSEDE BENEDICTA ONAKOYA 4 A A OYEGBADE 143 ABDULLAHI BILAL FATSUMA 282 ABIJOH BALIKIS ADESOLA 421 ABOSEDE DUPE ODUMADE 5 A A SIJUADE 144 ABDULLAHI BUKAR 283 ABIKE OTUSANYA 422 ABOSEDE JEMILA IBRAHIM 6 A BASHIR IRON BABA 145 ABDULLAHI DAN ASABE MOHAMMED 284 ABIKELE GRACE 423 ABOSEDE OLAYEMI OJO 7 A. ADESIHMA FAJEMILEHIN 146 ABDULLAHI DIKKO KASSIM (ALH) 285 ABIMBADE ATANDA WOJUADE 424 ABOSEDE OLUBUNMI SALAU (MISS) 8 A. AKINOLA 147 ABDULLAHI ELEWUETU YAHAYA (ALHAJI) 286 ABIMBOLA ABENI BAMGBOYE 425 ABOSEDE OMOLARA AWONIYI (MRS) 9 A. OLADELE JACOB 148 ABDULLAHI GUNDA INUSA 287 ABIMBOLA ABOSEDE OGUNNIEKAN 426 ABOSEDE OMOTUNDE ABOABA 10 A. OYEFUNSO OYEWUNMI 149 ABDULLAHI HALITA MAIBASIRA 288 ABIMBOLA ALICE ALADE 427 ABOSI LIVINUS OGBUJI 11 A. RAHMAN BUSARI 150 ABDULLAHI HARUNA 289 ABIMBOLA AMUDALAT BALOGUN 428 ABRADAN INVESTMENTS LIMITED 12 A.A. UGOJI 151 ABDULLAHI IBRAHIM RAIYAHI 290 ABIMBOLA AREMU 429 ABRAHAM A OLADEHINDE 13 AAA STOCKBROKERS LTD 152 ABDULLAHI KAMATU 291 ABIMBOLA AUGUSTA 430 ABRAHAM ABAYOMI AJAYI 14 AARON CHIGOZIE IDIKA 153 ABDULLAHI KURAYE 292 ABIMBOLA EKUNDAYO ODUNSI (MISS) 431 ABRAHAM ABU OSHIAFI 15 AARON IBEGBUNA AKABIKE 154 ABDULLAHI MACHIKA OTHMAN 293 ABIMBOLA FALI SANUSI-LAWAL 432 ABRAHAM AJEWOLE ARE 16 AARON M AMAK DAMAK 155 ABDULLAHI MAILAFIYA ABUBAKAR 294 ABIMBOLA FAUSAT ADELEKAN 433 ABRAHAM AJIBOYE OJEDELE 17 AARON OBIAKOR 156 ABDULLAHI MOHAMMED 295 ABIMBOLA FEHINTOLA 434 ABRAHAM AKEJU OMOLE 18 AARON OLUFEMI 157 ABDULLAHI MOHAMMED ABDULLAHI 296 ABIMBOLA KEHINDE OLUWATOYIN 435 ABRAHAM AKINDELE TALABI 19 AARON U. -

Facts and Figures About Niger State Table of Content

FACTS AND FIGURES ABOUT NIGER STATE TABLE OF CONTENT TABLE DESCRIPTION PAGE Map of Niger State…………………………………………….................... i Table of Content ……………………………………………...................... ii-iii Brief Note on Niger State ………………………………………................... iv-vii 1. Local Govt. Areas in Niger State their Headquarters, Land Area, Population & Population Density……………………................... 1 2. List of Wards in Local Government Areas of Niger State ………..…... 2-4 3. Population of Niger State by Sex and Local Govt. Area: 2006 Census... 5 4. Political Leadership in Niger State: 1976 to Date………………............ 6 5. Deputy Governors in Niger State: 1976 to Date……………………...... 6 6. Niger State Executive Council As at December 2011…........................ 7 7. Elected Senate Members from Niger State by Zone: 2011…........…... 8 8. Elected House of Representatives’ Members from Niger State by Constituency: 2011…........…...………………………… ……..……. 8 9. Niger State Legislative Council: 2011……..........………………….......... 9 10. Special Advisers to the Chief Servant, Executive Governor Niger State as at December 2011........…………………………………...... 10 11. SMG/SSG and Heads of Service in Niger State 1976 to Date….….......... 11 12. Roll-Call of Permanent Secretaries as at December 2011..….………...... 12 13. Elected Local Govt. Chairmen in Niger State as at December 2011............. 13 14. Emirs in Niger State by their Designation, Domain & LGAs in the Emirate.…………………….…………………………..................................14 15. Approximate Distance of Local Government Headquarters from Minna (the State Capital) in Kms……………….................................................. 15 16. Electricity Generated by Hydro Power Stations in Niger State Compare to other Power Stations in Nigeria: 2004-2008 ……..……......... 16 17. Mineral Resources in Niger State by Type, Location & LGA …………. 17 ii 18. List of Water Resources in Niger State by Location and Size ………....... 18 19 Irrigation Projects in Niger State by LGA and Sited Area: 2003-2010.…. -

Education Sector Support Programme in Nigeria (ESSPIN) Assignment Report School Based Management Committee (SBMC) Development

Education Sector Support Programme in Nigeria (ESSPIN) Assignment Report School Based Management Committee (SBMC) Development: Progress Report 5 Report Number: ESSPIN 412 Sulleiman Adediran & Mohammed Bawa 29 March 2010 www.esspin.org SBMC Development: Progress Report 5 Report Distribution and Revision Sheet Project Name: Education Sector Support Programme in Nigeria Code: 244333TA02 Report No.: ESSPIN 412 Report Title: School Based Management Committee Development: Progress Report 5 Rev No Date of issue Originator Checker Approver Scope of checking 1 February Sulleiman Adediran & Fatima Steve Formatting/ 2011 Mohammed Bawa Aboki Baines Checking Scope of Checking This report has been discussed with the originator and checked in the light of the requirements of the terms of reference. In addition the report has been checked to ensure editorial consistencies. Distribution List Name Position DFID Jane Miller Human Development Team Leader, DFID Barbara Payne Senior Education Adviser, DFID Roseline Onyemachi Education Project Officer, DFID ESSPIN Ron Tuck National Programme Manager Kayode Sanni Deputy Programme Manager Richard Hanson Assistant Programme Manager Steve Baines Technical Team Coordinator Gboyega Ilusanya State Team Leader Lagos Emma Williams State Team Leader Kwara Steve Bradley State Team Leader Kaduna Pius Elumeze State Team Leader Enugu Mustapha Ahmad State Team Leader Jigawa Pius Elumeze State Team Leader Enugu Jake Ross State Team Leader Kano John Kay Lead Specialist, Education Quality Alero Ayida‐Otobo Lead Specialist, Policy -

Nigeria- Cameroon Boundary Relations in the North of Nigeria, 1914- 94

International Affairs and Global Strategy www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-574X (Paper) ISSN 2224-8951 (Online) Vol.27, 2014 Nigeria- Cameroon Boundary Relations in the North of Nigeria, 1914- 94 Duyile Abiodun Department of History and International Studies, Faculty of Arts, Ekiti State University, Ado Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria Abstract This study looks at Northern Nigeria prior to the origination of the Court Case at The Hague in 1994. This research will review historical facts in context with the interpretations of Nigerian Boundary Commission before the commencement of the court case at The Hague. A retrospect of the facts will be made, in order that we understand the controversies that have ensued since the verdict on the case was made in 2001.The research will focus majorly on historical events before 1994. It will also discuss issues that concern the various boundary controversies in Northern Nigeria, through the facts on ground in Nigeria. The boundary crisis in Northern Nigeria correlates very much to the mistakes created by the colonial government. The boundary problems in Northern Nigeria are as contending as the border issues that ensued between Nigeria and Cameroon in the South of Nigeria. Although, the oil politics embedded in the Bakassi Peninsula dispute may have elevated the crisis in the South above that of the North. It is important to revisit Nigeria’s boundary crisis in the North with Cameroon so as to properly put into context Nigeria’s case at The Hague. The North of Nigeria was as turbulent in terms of boundary problems as that of the South; it is within this context that a study such as these will be significant to academics. -

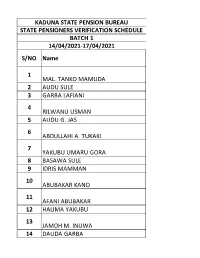

State Pensioners Verification Schedule 2021-Names

KADUNA STATE PENSION BUREAU STATE PENSIONERS VERIFICATION SCHEDULE BATCH 1 14/04/2021-17/04/2021 S/NO Name 1 MAL. TANKO MAMUDA 2 AUDU SULE 3 GARBA LAFIANI 4 RILWANU USMAN 5 AUDU G. JAS 6 ABDULLAHI A. TUKAKI 7 YAKUBU UMARU GORA 8 BASAWA SULE 9 IDRIS MAMMAN 10 ABUBAKAR KANO 11 AFANI ABUBAKAR 12 HALIMA YAKUBU 13 JAMOH M. INUWA 14 DAUDA GARBA 15 DAUDA M. UDAWA 16 TANKO MUSA 17 ABBAS USMAN 18 ADAMU CHORI 19 ADO SANI 20 BARAU ABUBAKAR JAFARU 21 BAWA A. TIKKU 22 BOBAI SHEMANG 23 DANAZUMI ABDU 24 DANJUMA A. MUSA 25 DANLADI ALI 26 DANZARIA LEMU 27 FATIMA YAKUBU 28 GANIYU A. ABDULRAHAMAN 29 GARBA ABBULLAHI 30 GARBA MAGAJI 31 GWAMMA TANKO 32 HAJARA BULUS 33 ISHAKU BORO 34 ISHAKU JOHN YOHANNA 35 LARABA IBRAHIM 36 MAL. USMAN ISHAKU 37 MARGRET MAMMAN 38 MOHAMMED ZUBAIRU 39 MUSA UMARU 40 RABO JAGABA 41 RABO TUKUR 42 SALE GOMA 43 SALISU DANLADI 44 SAMAILA MAIGARI 45 SILAS M. ISHAYA 46 SULE MUSA ZARIA 47 UTUNG BOBAI 48 YAHAYA AJAMU 49 YAKUBU S. RABIU 50 BAKO AUDU 51 SAMAILA MUSA 52 ISA IBRAHIM 53 ECCOS A. MBERE 54 PETER DOGO KAFARMA 55 ABDU YAKUBU 56 AKUT MAMMAN 57 GARBA MUSA 58 UMARU DANGARBA 59 EMMANUEL A. KANWAI 60 MARYAM MADAU 61 MUHAMMAD UMARU 62 MAL. ALIYU IBRAHIM 63 YANGA DANBAKI 64 MALAMA HAUWA IBRAHIM 65 DOGARA DOGO 66 GAIYA GIMBA 67 ABDU A. LAMBA 68 ZAKARI USMAN 69 MATHEW L MALLAM 70 HASSAN MAGAJI 71 DAUDA AUTA 72 YUSUF USMAN 73 EMMANUEL JAMES 74 MUSA MUHAMMAD 75 IBRAHIM ABUBAKAR BANKI 76 ABDULLAHI SHEHU 77 ALIYU WAKILI 78 DANLADI MUHAMMAD TOHU 79 MARCUS DANJUMA 80 LUKA ZONKWA 81 BADARAWA ADAMU 82 DANJUMA ISAH 83 LAWAL DOGO 84 GRACE THOT 85 LADI HAMZA 86 YAHAYA GARBA AHMADU 87 BABA A. -

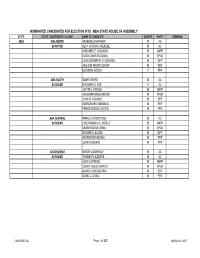

Nominated Candidates for Election Into Abia State

NOMINATED CANDIDATES FOR ELECTION INTO ABIA STATE HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY STATE STATE CONSTITUENCY & CODE NAME OF CANDIDATE GENDER PARTY REMARKS ABIA ABA NORTH AKOBUNDU NWANERI M AA SC/001/AB ALOY CHUKWU OKEREKE M AC OGBUMBA E. OGBUMBA M ANPP ELODI CHARLES AZUKA M APGA UGOCHINYERE N. E. UZUEGBU M DPP AKUJIOBI NKORO OSCAR M PDP BLESSING AZURU F PPA ABA SOUTH SMART EBERE M AA SC/002/AB EUCHARIA C. EZE F AC JUSTIN C. NWOGU M ANPP AHUKANNA MADUABUCHI M APGA JOHN M. OGUMIKE M DPP EMERUEUWA EMMANUEL M PDP PRINCE NWOGU OKORO M PPA ABA CENTRAL PRINCE CHIGBO IGWE M AC SC/003/AB CHIZARAMOKU A. OGBUJI M ANPP UBANI IRONUA UBANI M APGA GODWIN A. ELECHI M DPP OKORIE NWOKEOMA M PDP UZOR AZUBUIKE M PPA AROCHUKWU OKEZIE LAWRENCE M AA SC/004/AB THOMAS N. EZEIKPE M AC ALEX OJI EKUBO M ANPP UDENYI OKECHUKWU C. M APGA OKAFOR OKOREAFFIA M PDP AGWU U. UGWU M PPA CONFIDENTIAL Page 1 of 205 MARCH 14, 2007 BENDE NORTH OGWO UKACHI M. AA SC/005/AB DICKSON EJIAMA O. M. AC EKE ONYEMAUWA M. ANPP KALU ELIJAH AMAONWU M. APGA MICHAEL M. OFOR M. DPP UGWA SUNDAY M. PDP OJI LEKWAUWA M. PPA BENDE SOUTH IROEGBU FELIX M. AA SC/006/AB BARR. UCHE OGBONNAYA M. AC EGU N. EMMANUEL M. ANPP OLU-MORRIS I. NNENNA F APGA CHARLES CHUKWUDI M. DPP DIKE OKAY EMMANUEL M. PDP P. C. ONYEGBU M. PPA IKWUANO CHUKWU RAYMOND M AA SC/007AB UCHE F. MPAMAH M AC RICKSON UGOCHUKWU M ANPP CHUKWUEME OSOGBAKA M APGA DR. -

List of Youwin! 3 First Round Winners S/N Surname First Name Other Names Gender Date of Birth Zone

List of YouWiN! 3 First Round Winners S/N Surname First name Other names Gender Date of birth Zone 1 Aave Gabriel Male 1985-08-18 North-Central 2 Aba Noah Male 1978-06-11 North-Central 3 Abah Sunday Percy Male 1975-05-18 North-Central 4 Abang Melvile Egbeji Male 1984-01-03 North-Central 5 Abatta Folashade Female 1977-06-17 North-Central 6 Abayomi Sobakin Male 1979-05-05 North-Central 7 Abba Babagana Male 1974-06-15 North-Central 8 Abbe Elizabeth Ose Female 1984-11-01 North-Central 9 Abdul Zainab Sulaiman Female 1985-04-13 North-Central 10 Abdul Yetunde Emerald Female 1983-05-12 North-Central 11 Abdulazeez Halimat Female 1979-07-20 North-Central 12 Abdulazeez Ismaila Adewumi Male 1982-03-13 North-Central 13 Abdulganiyu Ahmed Yusuf Male 1985-02-28 North-Central 14 Abdulsalam Lukman Adebayo Male 1975-12-01 North-Central 15 Abednego Yemen Female 1987-08-09 North-Central 16 Abejide Dorcas Ropo Female 1983-09-04 North-Central 17 Abel Toyin Bamidele Male 1986-07-21 North-Central 18 Abiayi Simon Eberechukwu Male 1993-01-07 North-Central 19 Abiona James Folusho Male 1969-08-20 North-Central 20 Abodunde Adeleye Sam. Male 1985-04-16 North-Central 21 Abohwo Orunor Andrew Male 1979-02-10 North-Central 22 Aboje John Ngbede Male 1983-10-30 North-Central 23 Abok William Maina Male 1973-11-09 North-Central 24 Abolaji Odunola Opeyemi Male 1979-12-14 North-Central 25 Abu Abba Afenoko Male 1983-03-26 North-Central 26 Abubaka Oyiza Maimunat Female 1968-07-12 North-Central 27 Abubakar Abdulkadir Oyewale Male 1985-01-05 North-Central 28 Abubakar Adam Ofiji-Idah -

Education Sector Support Programme in Nigeria (ESSPIN) Assignment Report School Based Management Committee (SBMC) Development

Education Sector Support Programme in Nigeria (ESSPIN) Assignment Report School Based Management Committee (SBMC) Development: Progress Report 6 Report Number: ESSPIN 413 Sulleiman Adediran & Mohammed Bawa 31 May 2010 www.esspin.org SBMC Development: Progress Report 6 Report Distribution and Revision Sheet Project Name: Education Sector Support Programme in Nigeria Code: 244333TA02 Report No.: ESSPIN 413 Report Title: School Based Management Committee Development: Progress Report 6 Rev No Date of issue Originator Checker Approver Scope of checking 1 February Sulleiman Adediran & Fatima Steve Formatting/ 2011 Mohammed Bawa Aboki Baines Checking Scope of Checking This report has been discussed with the originator and checked in the light of the requirements of the terms of reference. In addition the report has been checked to ensure editorial consistencies. Distribution List Name Position DFID Jane Miller Human Development Team Leader, DFID Barbara Payne Senior Education Adviser, DFID Roseline Onyemachi Education Project Officer, DFID ESSPIN Ron Tuck National Programme Manager Kayode Sanni Deputy Programme Manager Richard Hanson Assistant Programme Manager Steve Baines Technical Team Coordinator Gboyega Ilusanya State Team Leader Lagos Emma Williams State Team Leader Kwara Steve Bradley State Team Leader Kaduna Pius Elumeze State Team Leader Enugu Mustapha Ahmad State Team Leader Jigawa Pius Elumeze State Team Leader Enugu Jake Ross State Team Leader Kano John Kay Lead Specialist, Education Quality Alero Ayida‐Otobo Lead Specialist, Policy -

Beyond Political Islam: Nigeria, the Boko Haram Crisis and the Imperative of National Consensus Simeon Onyemachi Hilary Alozieuwa Dr

Journal of Retracing Africa Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 5 January 2016 Beyond Political Islam: Nigeria, the Boko Haram Crisis and the Imperative of National Consensus Simeon Onyemachi Hilary Alozieuwa Dr. Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution, Abuja, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/jora Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Alozieuwa, Simeon Onyemachi Hilary Dr.. "Beyond Political Islam: Nigeria, the Boko Haram Crisis and the Imperative of National Consensus." Journal of Retracing Africa: Vol. 2, Issue 1 (2015): 49-72. https://encompass.eku.edu/jora/vol2/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Retracing Africa by an authorized editor of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alozieuwa | 49 Beyond Political Islam: Nigeria, the Boko Haram Crisis and the Imperative of National Consensus Simeon H.O. Alozieuwa Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution Abuja, Nigeria Abstract: The escalation of the Boko Haram crisis in Nigeria that peaked in 2010 has led to the emergence of many theories to explain its causes. These theories focus on the socio-economic/ human needs, vengeance, the Islamic theocratic state, and political dimensions. Beside the socio-economic perspective, which harps on the pervasive poverty in the North, the theocratic state analysis seems compelling not only because it fits into the sect’s mission to Islamize Northern Nigeria and carve it out as a distinct political entity, but it also resonates with political Islam, the driving ideology behind such Jihadi groups as Al-Qaeda in the Maghreb (AQIM) and Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) with which the sect has been linked. -

Muslin and Christian Governors in Nigerian North-Eastern States (1967-2015)

Muslin and Christian Governors in Nigerian North-Eastern states (1967-2015) State Governor/Administr Affiliatio Ethnic group / Religion Head of State Deputy Ethnic group / Religion ator n LGA (Federal) governor LGA 1) Brig. Musa Usman Military n.a. Muslim Gen. Yakubu n.a. n.a. n.a. North- (Apr 1968–Jul 1975 Gowon East State Muhammadu Buhari Military Fulani/Daura Muslim Gen. Murtala n.a. n.a. n.a. (created (Jul 1975 – Mar (Katsina State) Mohammed in May 1976) 1967 from the Northern Region. 2) Mohammed Jega Military Hausa/Jega Muslim Gen. Olusegun n.a. n.a. n.a. Adamaw (Mar 1976 – Jul (Kebbi State) Obasanjo a State 1978) (formerly Abdul Rahman Military n.a. Muslim Gen. Olusegun n.a. n.a. n.a. Gongola; Mamudu (Jul 1978 – Obasanjo created Oct 1979) out of Gongola and Abubakar Barde (Oct GNPP Mumuye/Jalingo Muslim Shehu Shagari Wilberforce Bachama/Numa Christian renamed 1979 – Oct 1983) (Taraba State) (NPN) Juta n (Adamawa Adamaw State) a in Wilberforce Juta (Oct GNPP Bachama/Numa Christian Shehu Shagari Bello Jidda Fulani/Fufore Muslim 1991) 1983) n (Adamawa (NPN) (Adamawa State) State) Bamanga Tukur (Oct NPN Fulani/Yola Muslim Shehu Shagari David Barau n.a. Christian 1983 – Dec 1983) North (NPN) (Adamawa State) Mohammed Jega (Jan Military Hausa/Jega Muslim Gen. n.a. n.a. n.a. 1984 – Aug 1985) (Kebbi State) Muhammadu Buhari Yohanna Madaki Military Atyap/Zangon Christian Gen. Ibrahim n.a. n.a. n.a. (Aug 1985 – Aug Kataf (Kaduna Babangida 1986) State) Jonah David Jang Military Berom/Jos Christian Gen. Ibrahim n.a. -

List of Candidates for Naf 2019 Trades and Non Tradesmen/Women Recruitment Interview

LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR NAF 2019 TRADES AND NON TRADESMEN/WOMEN RECRUITMENT INTERVIEW Serial Applicant ID Name Sex Remarks (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) BATCH A TO REPORT ON SUNDAY 9 - 15 JUNE 2019 ABIA STATE 1. NAF2019/165880 AARON NELSON CHIDERA M 2. NAF2019/187976 ADIKWU EMMANUEL ONYEDIKACHI M 3. NAF2019/083409 AMANDI UCHENNA M 4. NAF2019/197667 ANABA CHIBUIHE LIGHT M 5. NAF2019/051254 AZUKA TOCHUKWU M 6. NAF2019/029640 BENJAMIN MICHEAL CHUKWUEMEKA M 7. NAF2019/137189 BENJAMIN UCHE EZIGBO M 8. NAF2019/056039 BETHEL CHICHETEM EHURUBE M 9. NAF2019/017931 BLESSING IFEYINWA OBIOMA F 10. NAF2019/096551 BRIGHT CHIDERA ODOEMELAM M 11. NAF2019/051483 CALEB OKAFOR M 12. NAF2019/129087 CHIBUEZE DANIEL BENSON M 13. NAF2019/074928 CHIBUIHE AKARAWOLU M 14. NAF2019/163792 CHIDI ALFRED CHIMAOBI M 15. NAF2019/143032 CHIDIEBERE OSITA LAWRENCE M 16. NAF2019/092061 CHIDINMA MERCY DICKSON F 17. NAF2019/055225 CHIGOZIE MICHEAL EJIKEME M 18. NAF2019/024848 CHIMEZIRIN ETUGO M 19. NAF2019/085301 CHINATU LUCKY CHIDOZIE M 20. NAF2019/187920 CHINEDU ECHEMAZU NDUKWE M 21. NAF2019/132595 CHINEDU MOSES EFULA M 22. NAF2019/031292 CHINEMEREM NELSON IROBUNDA M 23. NAF2019/096799 CHINONSO EDWIN CHIKEZIE M 24. NAF2019/174511 CHINONSO EMMANUEL UBANI M 25. NAF2019/096654 CHINYERE QUEEN SUNDAY F 26. NAF2019/040976 CHIOMA FAVOUR SAMUEL F 27. NAF2019/130214 CHISOM STEPHANIE EJIOFOR F 28. NAF2019/084610 CHRISTAIN I CHIBUGWU M 29. NAF2019/092108 CHRISTIAN CHUKWUEMEKA JOHNSON M 30. NAF2019/017679 CHRISTOPHER UGORJI M 31. NAF2019/177010 CHUKWUDI CALEB OBIANUSI M 32. NAF2019/174757 CHUKWUDI UGURU NDUKWE M 33. NAF2019/024209 CHUKWUEMEKA SUNDAY ELUWA M 1 (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) 34. -

Teachers Registration Council of Nigeria, Headquarters, Abuja Professional Qualifying Examination October Diet 2018 List of Successful Candidates

TEACHERS REGISTRATION COUNCIL OF NIGERIA, HEADQUARTERS, ABUJA PROFESSIONAL QUALIFYING EXAMINATION OCTOBER DIET 2018 LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES ABIA STATE S/N NAME PQE NUMBER CAT 1 ORLU EGEONU SUCCESS AB/PQE/B018/R/00010 D 2 UDE OLA IKPA AB/PQE/B018/S/00004 D 3 NJOKU CHINYERE CALISTA AB/PQE/B018/R/00003 C 4 ELECHI MESOMA OKORONKWO AB/PQE/B018/R/00012 D 5 IFEGWU CATHERINE OLAMMA AB/PQE/B018/P/00002 D 6 NWAZUBA MARYROSE CHINENYE AB/PQE/B018/S/00010 D 7 UMEH EMMANUEL CHIMA AB/PQE/B018/R/00006 D 8 OKEKE JOY KALU AB/PQE/B018/P/00056 D 9 NWACHUKWU IFEANYI AB/PQE/B018/T/00001 B 10 NWAGBARA CHRISTIAN KELECHI AB/PQE/B018/S/00009 C 11 EKE KALU ELEKWA AB/PQE/B018/P/00004 C 12 AMANYIE LENEBARI DARLINGTON AB/PQE/B018/R/00039 D 13 ONWUKAEME MERCY CHINAGORO AB/PQE/B018/R/00037 D 14 UZOMAKA JOY CHIBUZO AB/PQE/B018/R/00009 D 15 KALU GLORY OGBU AB/PQE/B018/P/00030 D 16 UGBOR REJOICE AB/PQE/B018/S/00015 C 17 MADUKWE KOSARACHI WISDOM AB/PQE/B018/R/00001 C 18 DIBIA OGECHI MODESTA AB/PQE/B018/S/00016 C 19 ELECHI PATIENCE ADA AB/PQE/B018/R/00016 D 20 UGWU CALISTUS TOBECHUKWU AB/PQE/B018/R/00022 D 21 OKALI ONYINYECHI NJOKU AB/PQE/B018/R/00026 D 22 NWOSU ONYINYECHI PRISCILIA AB/PQE/B018/P/00046 D 23 OHAJURU KEZIAH NKEIRU AB/PQE/B018/P/00038 C 24 IZUWA NNEAMAKA IJEOMA AB/PQE/B018/S/00014 C 25 UKWEN ROSEMARY OLE AB/PQE/B018/P/00001 C 26 COLLINS MICHAEL UGOCHUKWU AB/PQE/B018/P/00057 D 27 ASSIAN UKEME EDET AB/PQE/B018/R/00018 D 28 EYET JAMES JAMES AB/PQE/B018/R/00023 D 29 IGBOAMAGH ONUOHA AMARACHI AB/PQE/B018/R/00007 D 30 OHIA JULIET UCHENNA AB/PQE/B018/P/00014