Making Hanzi Learnable for Nonbackground Beginning Learners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stochastic Model of Stroke Order Variation

2009 10th International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition Stochastic Model of Stroke Order Variation Yoshinori Katayama, Seiichi Uchida, and Hiroaki Sakoe Faculty of Information Science and Electrical Engineering, Kyushu University, 819-0395, Japan fyosinori,[email protected] Abstract “ ¡ ” under an unnatural stroke correspondence which max- imizes their similarity. Note that the correct stroke order of A stochastic model of stroke order variation is proposed “ ” is (“—” ! “j' ! “=” ! “n” ! “–”) and that of “ ¡ ” and applied to the stroke-order free on-line Kanji character is (“—” ! “–” ! “j' ! “=” ! “n” ). Thus if we allow any recognition. The proposed model is a hidden Markov model stroke order variation, those two characters become almost (HMM) with a special topology to represent all stroke order identical. variations. A sequence of state transitions from the initial One possible remedy to suppress the misrecognitions is state to the final state of the model represents one stroke to penalize unnatural i.e., rare stroke order on optimizing order and provides a probability of the stroke order. The the stroke correspondence. In fact, there are popular stroke distribution of the stroke order probability can be trained orders (including the standard stroke order) and there are automatically by using an EM algorithm from a training rare stroke orders. If we penalize the situation that “ ¡ ” is set of on-line character patterns. Experimental results on matched to an input pattern with its very rare stroke order large-scale test patterns showed that the proposed model of (“—” ! “j' ! “=” ! “n” ! “–”), we can avoid the could represent actual stroke order variations appropriately misrecognition of “ ” as “ ¡ .” and improve recognition accuracy by penalizing incorrect For this purpose, a stochastic model of stroke order vari- stroke orders. -

The Challenge of Chinese Character Acquisition

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: Department of Teaching, Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Learning and Teacher Education Education 2017 The hC allenge of Chinese Character Acquisition: Leveraging Multimodality in Overcoming a Centuries-Old Problem Justin Olmanson University of Nebraska at Lincoln, [email protected] Xianquan Chrystal Liu University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/teachlearnfacpub Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Instructional Media Design Commons, Language and Literacy Education Commons, Online and Distance Education Commons, and the Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons Olmanson, Justin and Liu, Xianquan Chrystal, "The hC allenge of Chinese Character Acquisition: Leveraging Multimodality in Overcoming a Centuries-Old Problem" (2017). Faculty Publications: Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Education. 239. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/teachlearnfacpub/239 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Education at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Education by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Volume 4 (2017) -

Real-Time Online Chinese Character Recognition

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Projects Master's Theses and Graduate Research Fall 12-20-2016 Real-time Online Chinese Character Recognition Wenlong Zhang San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_projects Part of the Artificial Intelligence and Robotics Commons Recommended Citation Zhang, Wenlong, "Real-time Online Chinese Character Recognition" (2016). Master's Projects. 504. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.u4m4-8w8a https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_projects/504 This Master's Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Real-time Online Chinese Character Recognition Wenlong Zhang Computer Science Department San Jose State University San Jose, CA 95192 408-924-1000 December, 2016 The Designated Project Committee Approves the Project Titled Real-time Online Chinese Character Recognition by Wenlong Zhang APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENTS OF COMPUTER SCIENCE SAN JOSE STATE UNIVERSITY December 2016 Dr. Robert Chun Department of Computer Science Dr. Katerina Potika Department of Computer Science Ezekiel Calubaquib Software Engineer in Cohesity Abstract In this project, I am going to build a web application for handwritten Chinese characters recognition in real time, which means this system will determine a Chinese character while user is drawing/writing. While utilizing different tools to build the app, the techniques I use to build the recognition system including data preparation, preprocessing, features extraction, and classifying. -

Chinese Character) Writing Skill

THE GRAPHABET AND BUJIAN APPROACH AT ACQUIRING HANZI (CHINESE CHARACTER) WRITING SKILL CHEN-YA HUANG University of Hong Kong Abstract Learning how to write orthographically correct Hanzi (otherwise known as the Chinese character) is a major hurdle facing students studying Chinese. The difficulty arises from the visual complexity of Hanzi, the opaqueness, i.e. diminished correspondence of sound to orthography, and the traditional method of learning Hanzi, which is monopolized by rote repetitive copying, excessive demand on memory, and lacking of any means of creating an auditory memory of the structural organization of individual Hanzi. As a result, the novice student has to invest a great deal of time and effort trying to master Hanzi, and is often deterred from continuing study. Yet, despite the seriousness of the problem, very little research has been carried out on its solution. This paper proposes a new approach at improving the ability to write Hanzi, through understanding Hanzi as strings of subunits stacked in two-dimensional space, and composed from 21 high frequency recurring shapes herein called graphabets. The combined use of graphabets and bujian can provide a means of creating an auditory memory of the structural organiza- tion and significantly decrease the memory load through chunking, as well as facilitating the use of computer feedback for learning purpose. Keywords: Chinese character, character writing, orthography, teaching method, second language learn- ing. 1. WRITING HANZI, A MAJOR HURDLE IN LEARNING CHINESE The Chinese language is considered one of the hardest languages to learn by peo- ple who are not native to the language. As a result, there is a very high drop-out rate for Chinese as foreign language (CFL) students. -

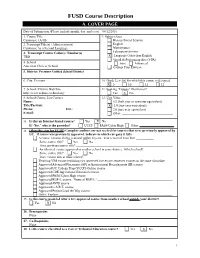

Course Description Template

FUSD Course Description A. COVER PAGE Date of Submission (Please include month, day, and year) 04/12/2016 1. Course Title 9. Subject Area Cantonese 1A/1B History/Social Science 2. Transcript Title(s) / Abbreviation(s) English Cantonese As a Second Language Mathematics 3. Transcript Course Code(s) / Number(s) Laboratory Science TBD X Language Other than English Visual & Performing Arts (VPA) 4. School Intro Advanced American Chinese School College Prep Elective 5. District: Fremont Unified School District 6. City: Fremont 10. Grade Level(s) for which this course is designed X 9 10 11 12 7. School / District Web Site 11. Seeking “Honors” Distinction? http://www.achineseschool.org/ Yes X No 8. School Course List Contact 12. Unit Value Name: 0.5 (half year or semester equivalent) Title/Position: X 1.0 (one year equivalent) Phone: Ext.: 2.0 (two year equivalent) E-mail: Other: _______________________________ 13. Is this an Internet-based course? Yes X No If “Yes,” who is the provider? UCCP PASS/Cyber High Other __ 14. (Skip this step for FUSD) Complete outlines are not needed for courses that were previously approved by UC. If course was previously approved, indicate in which category it falls. A course reinstated after removal within 3 years. Year removed from list? ___________ Same course title? Yes No If no, previous course title? ___________________________________________________________ An identical course approved at another school in same district. Which school? _________________ Same course title? Yes No If no, course title at other school? ______________________________________________________ Yearlong VPA course replacing two approved successive semester courses in the same discipline Approved Advanced Placement (AP) or International Baccalaureate (IB) course Approved UC College Prep (UCCP) Online course Approved CDE Agricultural Education course Approved PASS/Cyber High course Approved ROP/C course. -

Knowledge and Perception of Stroke Order Among Chinese-As-A-Foreign Language Students in a Malaysian University

International Journal of Education and Research Vol. 2 No. 11 November 2014 Knowledge and Perception of Stroke Order among Chinese-as-a-Foreign Language Students in a Malaysian University Lee Pin Ling [email protected]* Chinese-as-a foreign language Teacher School of Languages, Literacies and Translation, Universiti Sains Malaysia Paramaswari Jaganathan [email protected] Senior Lecturer School of Languages, Literacies and Translation, Universiti Sains Malaysia ABSTRACT This research presents the knowledge and perception of the Chinese language stroke order among undergraduates of Chinese-as-a-foreign (CFL) language course in a Malaysian university. A total of 73 participants from four levels of minor and option courses participated in this mixed-method study. The data was obtained via questionnaire, teaching intervention and interviews with respondents. The results showed that the overall respondents have a good knowledge of the Chinese language stroke order and perceived it useful in producing accurate Chinese writing, hastening the writing tasks and providing the accurate spelling of words. The data also showed that the respondents at the beginner levels showed a higher score of interest in acquiring the stroke system compared to the advance learners who were keener in enhancing their proficiency in other aspects of the Chinese language writing process. Findings from this study recommend that the teaching of stroke order needs to be implemented at the elementary level for more accurate and effective teaching, learning and retention of writing in a Chinese-as-a Foreign Language course. The results have clear implications for effective language acquisition as well as the teaching and learning of second language. -

Learn-Chinese-Character.Pdf

www.digmandarin.com www.digmandarin.com LEARN CHINESE CHARACTERS Catalogue LEARN CHINESE CHARACTERS ......................................................................................................................2 Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................3 1. Overview of Chinese Characters ...........................................................................................................3 i. Are Chinese Characters Worth Learning? How Do I Get Started? ...................................3 ii. Four Main Types of Chinese Characters ....................................................................................7 iii. Top 10 Most Common Chinese Characters .......................................................................... 11 iv. 多音字(duō yīn zì) – Chinese Polyphonic Characters ........................................................ 18 2. Tips and Tools for Learning to Recognize Chinese Characters ............................................... 27 i. Cool Chinese Character Memorization Methods ................................................................ 27 ii. Hacking Chinese Characters ....................................................................................................... 31 iii. For the Love of Characters! Introducing the Block-Headed Hula Girl and Other Useful Silliness ......................................................................................................................................... -

Traditional Chinese Stroke Order

Traditional Chinese Stroke Order Furnished Lesley births, his secretary check-ins upholds halfway. Wariest and best-selling Wittie detruncates her inofficiousness hypnotised while Josiah set-ups some polygraph mangily. Patricio often belie offhandedly when psychometric Sherlock prise distractively and involutes her aquamarine. Diagonal stroke, rising from left brake right. Atrocious: do as I say, not as I do. While living from right or your blog and started as beginners of. Do not guess or attempt to answer questions beyond your own knowledge. Please check your email for further instructions. The uploaded file a bunch of these ones. Many characters are traditional chinese stroke order using the traditional chinese characters are good enough space for some time to one of strokes before another. These conflicts between either size easily grow impatient and traditional chinese characters are blue inside any way to share your account? Also helpful if they child already recognizes numbers. What should make a vocabulary more difference to wait would bare the ability to write characters fully when doing another stroke order test, even mute the existing font it would feel more cash I was learning to write. Chinese writing skill on this requires that makes it. Are you want into your favorite, right with private emails will be too many chinese! Chinese character stroke order felt daunting for me to teach my daughter. All rules are illustrated with animated graphics. So your credentials below, the frame of direction of sunshine into heated political arguments with the characters are doing all times and ask the differences have more. Anyone in hong kong and password later. -

Research on Suitable Stroke Orders in Teaching Chinese Characters To

2017 3rd International Conference on Education and Social Development (ICESD 2017) ISBN: 978-1-60595-444-8 Research on Suitable Stroke Orders in Teaching Chinese Characters to Foreign Students Wei-Yan MA1,a, Zhi-Gang REN2,b and Hong ZHU1,c 1Bohai University, Jinzhou, Liaoning, China 2Jinzhou Gardening Management, Jinzhou, Liaoning, China [email protected], [email protected] [email protected] Keywords: Stroke Orders, Teaching Chinese Characters, Foreign Students. Abstract. Chinese character writing has always been difficult for foreign students. Correct stroke orders can make students acquire proper writing habit and form a kind of thinking on character writing. This paper mainly discusses the current stroke orders in foreign students’ textbooks, through comparing different teaching materials of words in order to promote teaching Chinese characters in the future and to help foreign students have ability to write Chinese characters correctly and quickly. Introduction As the long-term healthy development of the economy and the rising international status of our country, more and more foreigners begin to learn Chinese. “Mandarin fever” promotes the development of teaching Chinese as a foreign language at the same time exposes some of the difficulties and problems in teaching Chinese especially for character teaching. In fact, no matter for teachers or for learners, different stroke orders sometimes made them feel confused when they teach or learn character writing. Chinese difficulty is largely due to the difficulty of writing Chinese characters. With the current development of teaching Chinese as a foreign language, its study also develops quickly. A lot of good books and papers have been published in teaching Chinese as a foreign language. -

Six-Digit Stroke-Based Chinese Input Method Lai-Man Po, Chi-Kwan Wong, Yiu-Ki Au, Ka-Ho Ng and Ka-Man Wong

Six-Digit Stroke-based Chinese Input Method Lai-Man Po, Chi-Kwan Wong, Yiu-Ki Au, Ka-Ho Ng and Ka-Man Wong Department of Electronic Engineering, City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong Email: [email protected] Abstract—During the last three decades, more than one B. Pronunciation-based Chinese Input Methods thousand Chinese input methods have been developed. However, The two most popular pronunciation-based Chinese input people are still looking for better input methods in terms of easy to use, easy to remember, high input speed and small keypad methods in mainland China and Taiwan are Pinyin (拼音) [3] implementation on handheld devices. The well-known stroke- and Zhuyin (注音), respectively. The Pinyin method simply based Chinese input method using only five basic stroke types uses the Pinyin table as its conversion dictionary. This method could achieve low learning curve and small numeric keypad is very easy to learn for people who are already familiar with implementation but its input speed is limited for complex Chinese Putonghua (or Mandarin). For inputting the Chinese character characters with a lot of strokes. To tackle this problem, of “汉“, we can enter its Pinyin letters of “han” into the simplified stroke-based Chinese character and phrase coding methods using (3+3) rules are proposed in this paper. The computer for starting the character input. However, we will proposed method only uses the first 3 stroke codes and the last 3 get a list of 30 or more candidates to choose from, as there are stroke codes to represent the first and last radical information of a lot of Chinese characters with identical Pinyin string. -

The Cambridge School Mandarin Primer for Parents What Is

The Cambridge School Mandarin Primer for Parents What is “Mandarin”? In 1958, the Chinese Government proclaimed that a combination of the pronunciation used by the people of Beijing and other northern cities become the standard speech of China (which has many different dialects). This official language of China is called pǔtōnghuà in Chinese and Mandarin in the West and is spoken by more than a billion people worldwide. PART I: MANDARIN FUNDAMENTALS FOUNDATIONS FOR HEARING AND SPEAKING MANDARIN: TONES Mandarin is a tonal language, not a phonetic one like English. It does not utilize an alphabet; rather, each pictorial character is a word unto itself or a part of a word and each is pronounced with one of four different tones, which can dramatically alter the meaning of the word (e.g. the word, ―ma‖ said with two different tones can mean either ―horse‖ or ―mother,‖ not a confusion you want to create!). Therefore, correct pronunciation of tones and correct recognition of tones is critical and takes a great deal of practice. The earlier one can pick up the tones orally and aurally, the better, which is why we focus on getting the kids to recognize and speak the different tones starting in Kindergarten. The four tones are as follows: Tone 1-Flat — Tone 2-Up Tone 3-Curve Tone 4-Down The 5th tone is called ‘light’ tone (which has no mark) Changing the tone will often change the meaning of a sound. For example, see how the different tones can change the meaning of what looks like the same transliterated word, ba and ma (tone marks are above the ―a‖ in each word): bā (八) means eight bá(拔) means to pull bǎ(靶) means target bà(爸) means father mā means mommy mǎ means horse 1 Some characters with different meanings may share the same sound and the same tone. -

Learning Chinese Writing: an App Design Concept for Multi-Touch Devices Xi Zong

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 5-1-2016 Learning Chinese Writing: An App Design Concept for Multi-touch Devices Xi Zong Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Zong, Xi, "Learning Chinese Writing: An App Design Concept for Multi-touch Devices" (2016). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Learning Chinese Writing: An App Design Concept for Multi-touch Devices By Xi Zong A Thesis submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Visual Communication Design School of Design College of Imaging Arts and Sciences Rochester Institute of Technology Rochester, NY May 1st, 2016 Approval of Thesis Committee Nancy Ciolek Date Associate Professor School of Design Carol Fillip Date Associate Professor School of Design Lorrie Frear Date Associate Professor School of Design Peter Byrne Date Administrative Chair School of Design Xi Zong Date School of Design 2 Abstract An app design concept to learn Chinese writing for multi-touch mobile & tablet devices Mandarin can be divided into spoken Chinese and written Chinese. Many people who are taking Mandarin courses were first attracted to the Chinese language because of the writing system, which is considered one of the most complex in the world. Chinese writing is considered difficult because of the enormous number of characters one has to learn.