Literary Lab Pamphlet 13 October 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2016 Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945 Danielle K. Dodson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.339 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dodson, Danielle K., "Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--History. 40. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/40 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Karl Brunner and UK Monetary Debate

Finance and Economics Discussion Series Divisions of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs Federal Reserve Board, Washington, D.C. Karl Brunner and U.K. Monetary Debate Edward Nelson 2019-004 Please cite this paper as: Nelson, Edward (2019). \Karl Brunner and U.K. Monetary Debate," Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2019-004. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, https://doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2019.004. NOTE: Staff working papers in the Finance and Economics Discussion Series (FEDS) are preliminary materials circulated to stimulate discussion and critical comment. The analysis and conclusions set forth are those of the authors and do not indicate concurrence by other members of the research staff or the Board of Governors. References in publications to the Finance and Economics Discussion Series (other than acknowledgement) should be cleared with the author(s) to protect the tentative character of these papers. Karl Brunner and U.K. Monetary Debate Edward Nelson* Federal Reserve Board November 19, 2018 Abstract Although he was based in the United States, leading monetarist Karl Brunner participated in debates in the United Kingdom on monetary analysis and policy from the 1960s to the 1980s. During the 1960s, his participation in the debates was limited to research papers, but in the 1970s, as monetarism attracted national attention, Brunner made contributions to U.K. media discussions. In the pre-1979 period, he was highly critical of the U.K. authorities’ nonmonetary approach to the analysis and control of inflation—an approach supported by leading U.K. Keynesians. In the early 1980s, Brunner had direct interaction with Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher on issues relating to monetary control and monetary strategy. -

17 River Prospect: Golden Jubilee/ Hungerford Footbridges

17 River Prospect: Golden Jubilee/ 149 Hungerford Footbridges 285 The Golden Jubilee/Hungerford Footbridges flank the Hungerford railway bridge, built in 1863. The footbridges were designed by the architects Lifschutz Davidson and were opened as a Millennium Project in 2003. 286 There are two Viewing Locations at Golden Jubilee/Hungerford Footbridges, 17A and 17B, referring to the upstream and downstream sides of the bridge. 150 London View Management Framework Viewing Location 17A Golden Jubilee/Hungerford Footbridges: upstream N.B for key to symbols refer to image 1 Panorama from Assessment Point 17A.1 Golden Jubilee/Hungerford Footbridges: upstream - close to the Lambeth bank Panorama from Assessment Point 17A.2 Golden Jubilee/Hungerford Footbridges: upstream - close to the Westminster bank 17 River Prospect: Golden Jubilee/Hungerford Footbridges 151 Description of the View 287 Two Assessment Points are located on the upstream side of Landmarks include: the bridge (17A.1 and 17A.2) representing the wide swathe Palace of Westminster (I) † of views available. A Protected Silhouette of the Palace of Towers of Westminster Abbey (I) Westminster is applied between Assessment Points 17A.1 The London Eye and 17A.2. Westminster Bridge (II*) Whitehall Court (II*) 288 The river dominates the foreground. In the middle ground the London Eye and Embankment trees form distinctive Also in the views: elements. The visible buildings on Victoria Embankment The Shell Centre comprise a broad curve of large, formal elements of County Hall (II*) consistent height and scale, mostly of Portland stone. St Thomas’s Hospital (Victorian They form a strong and harmonious building line. section) (II) St George’s Wharf, Vauxhall 289 The Palace of Westminster, part of the World Heritage Site, Millbank Tower (II) terminates the view, along with the listed Millbank Tower. -

London Office Policy Review 2012

London Office Policy Review 2012 Prepared for: Greater London Authority 1 By RAMIDUS CONSULTING LIMITED Date: September 2012 London Office Policy Review 2012 London Office Policy Review 2012 By Ramidus Consulting Limited with Roger Tym & Partners September 2012 Dedication During the preparation of this report one of the principal authors died very suddenly. David Chippendale had been involved in the LOPR since its inception, and has played a major part in laying sound foundations for what is now seen as the authoritative review of London office policy. David was a leading personality of the property research industry and will be hugely missed by many friends and colleagues. We dedicate LOPR 12 to David’s memory. Acknowledgements Ramidus Consulting Limited was appointed in February 2012 to undertake LOPR 12. The team comprised Rob Harris, David Chippendale, Ian Cundell and Sandra Jones. We have worked very closely with Dave Lawrence and Adala Leeson of Roger Tym & Partners, who have provided invaluable input to the forecasting and policy analysis. Martin Davis of DTZ and Theresa Keogh and Hannah Lakey of EGi have once again provided data, and we thank them for their assistance. Prepared for: Greater London Authority i By RAMIDUS CONSULTING LIMITED Date: September 2012 London Office Policy Review 2012 Contents Page Management summary v 1.0 Supply and demand in Central London 1 1.1 The Central London office market in context 1.2 Market and planning data in Central London 1.3 Central London availability and take-up overview 1.4 Central London -

Social Studies of Science

Social Studies of Science http://sss.sagepub.com Mind the Gap: The London Underground Map and Users' Representations of Urban Space Janet Vertesi Social Studies of Science 2008; 38; 7 DOI: 10.1177/0306312707084153 The online version of this article can be found at: http://sss.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/38/1/7 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Social Studies of Science can be found at: Email Alerts: http://sss.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://sss.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Citations http://sss.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/38/1/7 Downloaded from http://sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF TEXAS AUSTIN on December 23, 2009 ABSTRACT This paper explores the effects of iconic, abstract representations of complex objects on our interactions with those objects through an ethnographic study of the use of the London Underground Map to tame and enframe the city of London. Official reports insist that the ‘Tube Map’s’ iconic status is due to its exemplary design principles or its utility for journey planning underground. This paper, however, presents results that suggest a different role for the familiar image: one of an essential visual technology that stands as an interface between the city and its user, presenting and structuring the points of access and possibilities for interaction within the urban space. The analysis explores the public understanding of an inscription in the world beyond the laboratory bench, the indexicality of the immutable mobile’s visual language, and the relationship between representing and intervening. -

Iain Sinclair and the Psychogeography of the Split City

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Iain Sinclair and the psychogeography of the split city https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40164/ Version: Full Version Citation: Downing, Henderson (2015) Iain Sinclair and the psychogeog- raphy of the split city. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email 1 IAIN SINCLAIR AND THE PSYCHOGEOGRAPHY OF THE SPLIT CITY Henderson Downing Birkbeck, University of London PhD 2015 2 I, Henderson Downing, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Abstract Iain Sinclair’s London is a labyrinthine city split by multiple forces deliriously replicated in the complexity and contradiction of his own hybrid texts. Sinclair played an integral role in the ‘psychogeographical turn’ of the 1990s, imaginatively mapping the secret histories and occulted alignments of urban space in a series of works that drift between the subject of topography and the topic of subjectivity. In the wake of Sinclair’s continued association with the spatial and textual practices from which such speculative theses derive, the trajectory of this variant psychogeography appears to swerve away from the revolutionary impulses of its initial formation within the radical milieu of the Lettrist International and Situationist International in 1950s Paris towards a more literary phenomenon. From this perspective, the return of psychogeography has been equated with a loss of political ambition within fin de millennium literature. -

'Ungovernable'? Financialisation and the Governance Of

Governing the ‘ungovernable’? Financialisation and the governance of transport infrastructure in the London ‘global city-region’ February 2018 Peter O’Briena* Andy Pikea and John Tomaneyb aCentre for Urban and Regional Development Studies (CURDS), Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK NE1 7RU. Email: peter.o’[email protected]; [email protected] bBartlett School of Planning, University College London, Bartlett School of Planning, University College London, 620 Central House, 14 Upper Woburn Place, London, UK WC1H 0NN. Email: [email protected] *Corresponding author 1 Abstract The governance of infrastructure funding and financing at the city-region scale is a critical aspect of the continued search for mechanisms to channel investment into the urban landscape. In the context of the global financial crisis, austerity and uneven growth, national, sub-national and local state actors are being compelled to adopt the increasingly speculative activities of urban entrepreneurialism to attract new capital, develop ‘innovative’ financial instruments and models, and establish new or reform existing institutional arrangements for urban infrastructure governance. Amidst concerns about the claimed ‘ungovernability’ of ‘global’ cities and city-regions, governing urban infrastructure funding and financing has become an acute issue. Infrastructure renewal and development are interpreted as integral to urban growth, especially to underpin the size and scale of large cities and their significant contributions within national economies. Yet, oovercoming fragmented local jurisdictions to improve the governance and economic, social and environmental development of major metropolitan areas remains a challenge. The complex, and sometimes conflicting and contested inter-relationships at stake raise important questions about the role of the state in wrestling with entrepreneurial and managerialist governance imperatives. -

The Pound Sterling

ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE No. 13, February 1952 THE POUND STERLING ROY F. HARROD INTERNATIONAL FINANCE SECTION DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS PRINCETON UNIVERSITY Princeton, New Jersey The present essay is the thirteenth in the series ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE published by the International Finance Section of the Department of Economics and Social Institutions in Princeton University. The author, R. F. Harrod, is joint editor of the ECONOMIC JOURNAL, Lecturer in economics at Christ Church, Oxford, Fellow of the British Academy, and• Member of the Council of the Royal Economic So- ciety. He served in the Prime Minister's Office dur- ing most of World War II and from 1947 to 1950 was a member of the United Nations Sub-Committee on Employment and Economic Stability. While the Section sponsors the essays in this series, it takes no further responsibility for the opinions therein expressed. The writer's are free to develop their topics as they will and their ideas may or may - • v not be shared by the editorial committee of the Sec- tion or the members of the Department. The Section welcomes the submission of manu- scripts for this series and will assume responsibility for a careful reading of them and for returning to the authors those found unacceptable for publication. GARDNER PATTERSON, Director International Finance Section THE POUND STERLING ROY F. HARROD Christ Church, Oxford I. PRESUPPOSITIONS OF EARLY POLICY S' TERLING was at its heyday before 1914. It was. something ' more than the British currency; it was universally accepted as the most satisfactory medium for international transactions and might be regarded as a world currency, even indeed as the world cur- rency: Its special position waS,no doubt connected with the widespread ramifications of Britain's foreign trade and investment. -

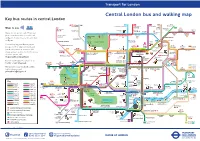

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

Gladstone and the Bank of England: a Study in Mid-Victorian Finance, 1833-1866

GLADSTONE AND THE BANK OF ENGLAND: A STUDY IN MID-VICTORIAN FINANCE, 1833-1866 Patricia Caernarv en-Smith, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Denis Paz, Major Professor Adrian Lewis, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Laura Stern, Committee Member Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Caernarven-Smith, Patricia. Gladstone and the Bank of England: A Study in Mid- Victorian Finance, 1833-1866. Master of Arts (History), May 2007, 378 pp., 11 tables, bibliography, 275 titles. The topic of this thesis is the confrontations between William Gladstone and the Bank of England. These confrontations have remained a mystery to authors who noted them, but have generally been ignored by others. This thesis demonstrates that Gladstone’s measures taken against the Bank were reasonable, intelligent, and important for the development of nineteenth-century British government finance. To accomplish this task, this thesis refutes the opinions of three twentieth-century authors who have claimed that many of Gladstone’s measures, as well as his reading, were irrational, ridiculous, and impolitic. My primary sources include the Gladstone Diaries, with special attention to a little-used source, Volume 14, the indexes to the Diaries. The day-to-day Diaries and the indexes show how much Gladstone read about financial matters, and suggest that his actions were based to a large extent upon his reading. In addition, I have used Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates and nineteenth-century periodicals and books on banking and finance to understand the political and economic debates of the time. -

Thames Path Walk Section 2 North Bank Albert Bridge to Tower Bridge

Thames Path Walk With the Thames on the right, set off along the Chelsea Embankment past Section 2 north bank the plaque to Victorian engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette, who also created the Victoria and Albert Embankments. His plan reclaimed land from the Albert Bridge to Tower Bridge river to accommodate a new road with sewers beneath - until then, sewage had drained straight into the Thames and disease was rife in the city. Carry on past the junction with Royal Hospital Road, to peek into the walled garden of the Chelsea Physic Garden. Version 1 : March 2011 The Chelsea Physic Garden was founded by the Worshipful Society of Start: Albert Bridge (TQ274776) Apothecaries in 1673 to promote the study of botany in relation to medicine, Station: Clippers from Cadogan Pier or bus known at the time as the "psychic" or healing arts. As the second-oldest stops along Chelsea Embankment botanic garden in England, it still fulfils its traditional function of scientific research and plant conservation and undertakes ‘to educate and inform’. Finish: Tower Bridge (TQ336801) Station: Clippers (St Katharine’s Pier), many bus stops, or Tower Hill or Tower Gateway tube Carry on along the embankment passed gracious riverside dwellings that line the route to reach Sir Christopher Wren’s magnificent Royal Hospital Distance: 6 miles (9.5 km) Chelsea with its famous Chelsea Pensioners in their red uniforms. Introduction: Discover central London’s most famous sights along this stretch of the River Thames. The Houses of Parliament, St Paul’s The Royal Hospital Chelsea was founded in 1682 by King Charles II for the Cathedral, Tate Modern and the Tower of London, the Thames Path links 'succour and relief of veterans broken by age and war'. -

Famous Places in London

Famous places in London Residenz der englischen Könige Sitz der britischen Regierung große Glocke, Wahrzeichen Londons großer Park in London Wachsfigurenkabinett Treffpunkt im Zentrum Londons berühmte Kathedrale ehemaliges Gefängnis, heute Museum, Kronjuwelen sind dort untergebracht berühmte Brücke, kann geöffnet werden, Wahrzeichen Londons großer Platz mit Nelson-Denkmal Krönungskirche des englischen Königshauses berühmte Markthallen berühmtes Warenhaus Riesenrad in London Sammelplatz für Unzufriedene, die die Menge mit ihren Schimpfreden unterhalten, im Hyde Park Sitz der englischen Kriminalpolizei Wohnsitz der königlichen Familie erstellt von Sabine Kainz für den Wiener Bildungsserver www.lehrerweb.at - www.kidsweb.at - www.elternweb.at Big Ben Scotland Yard Westminster Abbey Piccadilly Circus Hyde Park St. Paul’s Cathedral The Tower of London Tower Bridge Covent Garden Speakers Corner Houses of Parliament Buckingham Palace Trafalgar Square Madame Tussaud´s Harrods London Eye Kensington Palace erstellt von Sabine Kainz für den Wiener Bildungsserver www.lehrerweb.at - www.kidsweb.at - www.elternweb.at Famous places in London Buckingham Palace Residenz der englischen Könige Houses of Parliament Sitz der britischen Regierung Big Ben große Glocke, Wahrzeichen Londons Hyde Park großer Park in London Madame Tussaud´s Wachsfigurenkabinett Piccadilly Circus Treffpunkt im Zentrum Londons St. Paul’s Cathedral berühmte Kathedrale ehemaliges Gefängnis, heute The Tower of London Museum, Kronjuwelen sind dort untergebracht berühmte Brücke, kann geöffnet