Audience Reactions to Orientalist Stereotyping in I Dream of Jeannie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“I DREAM of JEANNIE” STAR RETURNS to SPACE COAST Barbara Eden to Perform at 50Th Anniversary of Iconic TV Series

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE “I DREAM OF JEANNIE” STAR RETURNS TO SPACE COAST Barbara Eden to Perform at 50th Anniversary of Iconic TV Series COCOA BEACH, FL – September 3, 2015. Barbara Eden, the star of the 1960s sitcom, “I Dream of Jeannie,” returns to Florida’s Space Coast on Sunday, October 25 for the 50th anniversary of the premiere of the iconic show set in Cocoa Beach, FL. “On the Magic Carpet with Barbara Eden” will feature Ms. Eden and “Entertainment Tonight” and Showtime movie reporter Bill Harris on stage at the Scott Center Auditorium on the campus of Holy Trinity Episcopal Academy in Melbourne. The performance will take guests back into Jeannie’s Magic Bottle in a fun-filled evening of storytelling and the screening of rare and never before seen film clips featuring Barbara Eden and such stars as Elvis Presley, Paul Newman, Frank Sinatra, Lucille Ball, Bob Hope, and her “I Dream of Jeannie” co-star Larry Hagman. The show will also include a lively Q & A session between Ms. Eden and the audience, in addition to a limited Meet & Greet reception following the performance. “The people of Cocoa Beach have always been so gracious and welcoming to me,” said Eden. “Even though we never actually filmed the show there, we have spent a lot of time on the Space Coast. It seems like a second home to me, and I am very excited to go back there and see so many familiar and friendly faces.” The show and Ms. Eden’s appearance are largely made possible due in part to the support of SCB Marketing and the Brevard County Tourism Development Council's Special Event Marketing Grant Program and the Space Coast Office of Tourism. -

I Dream of Jeannie Trivia Quiz

I DREAM OF JEANNIE TRIVIA QUIZ ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> In what year did the TV sitcom "I Dream of Jeannie" first air? a. 1965 b. 1975 c. 1972 d. 1970 2> What was the name of Anthony's best friend? a. George b. Roger c. Harvey d. Steve 3> What was Anthony Nelson's rank? a. General b. Colonel c. Major d. Lieutenant 4> What kind of craft was Major Nelson in when he crashed into the ocean? a. A jet plane b. A helicopter c. A glider d. A capsule 5> Where did Anthony Nelson live? a. Palm Springs b. Kissimmee c. Cocoa Beach d. Tampa 6> When casting a spell, what does Jeannie do? a. Twitch her nose b. Blink c. Chant d. Clap her hands 7> What is the name of the psychiatrist? a. Dr. Bellows b. Dr. Roberts c. Dr. Johnson d. Dr. Wilson 8> How old is Jeannie? a. 2,000 Years Old b. 500 Years Old c. 7,000 Years Old d. 10,000 Years Old 9> In which episode does Anthony's best friend discover that he has a Jeannie? a. The Moving Finger b. The Richest Astronaut in the Whole Wide World c. Guess What Happened on the Way to the Moon? d. The Americanization of Jeannie 10> When is Jeannie's birthday? a. May23 b. August 27 c. October 31 d. April 1 11> What is Anthony's address? a. 100 Date Avenue b. 1020 Palm Drive c. 776 Sunset Avenue d. 592 Oceanside Drive 12> What sport is Anthony supposed to play with General Peterson? a. -

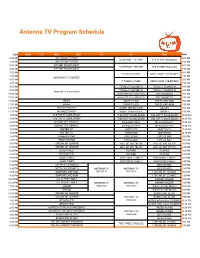

Antenna TV Program Schedule

Antenna TV Program Schedule East MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN West 5:00 AM BACHELOR FATHER 2:00 AM SUSPENSE THEATRE THE THREE STOOGES 5:30 AM BACHELOR FATHER 2:30 AM 6:00 AM FATHER KNOWS BEST 3:00 AM SUSPENSE THEATRE THE THREE STOOGES 6:30 AM FATHER KNOWS BEST 3:30 AM 7:00 AM 4:00 AM IT TAKES A THIEF HERE COME THE BRIDES 7:30 AM 4:30 AM ANTENNA TV THEATER 8:00 AM 5:00 AM IT TAKES A THIEF HERE COME THE BRIDES 8:30 AM 5:30 AM 9:00 AM TOTALLY TOONED IN TOTALLY TOONED IN 6:00 AM 9:30 AM TOTALLY TOONED IN TOTALLY TOONED IN 6:30 AM ANTENNA TV THEATER 10:00 AM ANIMAL RESCUE CLASSICS (E/I) THE MONKEES 7:00 AM 10:30 AM ANIMAL RESCUE CLASSICS (E/I) THE MONKEES 7:30 AM 11:00 AM HAZEL SWAP TV (E/I) THE FLYING NUN 8:00 AM 11:30 AM HAZEL SWAP TV (E/I) THE FLYING NUN 8:30 AM 12:00 PM MCHALE'S NAVY WORD TRAVELS (E/I) GIDGET 9:00 AM 12:30 PM MCHALE'S NAVY WORD TRAVELS (E/I) GIDGET 9:30 AM 1:00 PM THE PATTY DUKE SHOW THE PATTY DUKE SHOW THE PATTY DUKE SHOW 10:00 AM 1:30 PM THE PATTY DUKE SHOW THE PATTY DUKE SHOW THE PATTY DUKE SHOW 10:30 AM 2:00 PM DENNIS THE MENACE MCHALE'S NAVY MCHALE'S NAVY 11:00 AM 2:30 PM DENNIS THE MENACE MCHALE'S NAVY MCHALE'S NAVY 11:30 AM 3:00 PM MISTER ED MISTER ED MISTER ED 12:00 PM 3:30 PM MISTER ED MISTER ED MISTER ED 12:30 PM 4:00 PM GREEN ACRES CIRCUS BOY CIRCUS BOY 1:00 PM 4:30 PM GREEN ACRES CIRCUS BOY CIRCUS BOY 1:30 PM 5:00 PM I DREAM OF JEANNIE ADV. -

Drama | 60 Minutes DAWSON’S CREEK TEENAGE FRIENDS COME of AGE in a SMALL Resort TOWN

MAD ABOUT YOU ....................................................3 my boys ....................................................4 married with children ....................................................5 THE nanny ....................................................6 men at work ....................................................7 WHO’S THE BOSS? ....................................................7 the king of queens ....................................................8 RULES OF ENGAGEMENT ....................................................8 THE JEFFERSONS ....................................................9 SILVER SPOONS ....................................................9 DIFF’RENT STROKES ..................................................10 I DREAM OF JEANNIE ..................................................10 •3• comedy Paul is a documentary film-maker with a penchant for obsessing over the minutae, and his wife Jamie is a fiery public relations specialist. Together, these two young, urban newlyweds try to A SOPHISTICATED MARRIED COUPLE NAVIGATE sustain wedded bliss despite the demands of their respective professional careers, meddling MAD ABOUT YOU THE CHALLENGES OF MARRIAGE AND PARENTHOOD. friends (like Fran Devanow, Jamie’s first boss and eventual best friend, Ira, Paul’s cousin, and Lisa, Jamie’s offbeat older sister) in the chaos of big city living… always with honesty and humor. view promo comedy | 30 minutes •4• comedy MY BOYS A FEMALE SPORTS COLUMNIST DEALS WITH THE MEN IN HER LIFE comedy | 30 minutes view promo INCLUDING -

Copy of Metoo Q4 2010

WCIU-TV 26.4 • Comcast 247/358 • RCN 22 • WOW 171 • AT&T U-verse 23 Effective 12/15/2010 SUBJECT TO CHANGE Monday-Friday Saturday Sunday 5:00AM First Business Sponsored The Courtship of Eddie's Father 5:00AM 5:30 Sponsored Sponsored The Courtship of Eddie's Father 5:30 6:00 Dennis the Menace Sponsored Sponsored 6:00 6:30 Father Knows Best First Business Chicago NOW.Chicago 6:30 7:00 Green Screen Adventures E/I Wild America E/I Little House on the Prairie 7:00 7:30 Silver Spoons The Monkees 7:30 8:00 One Day at a Time The Partridge Family Little House on the Prairie 8:00 8:30 Maude Sponsored 8:30 9:00 The Cosby Show Saved by the Bell Here Come The Brides 9:00 9:30 The Cosby Show Sponsored 9:30 10:00 Who's The Boss The Addams Family Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries 10:00 10:30 Who's The Boss Sponsored 10:30 11:00 Sanford & Son Cheers Hart to Hart 11:00 11:30 The Jeffersons Cheers 11:30 12:00PM The Andy Griffith Show Barney Miller It Takes a Thief 12:00PM 12:30 The Andy Griffith Show Barney Miller 12:30 1:00 Leave It To Beaver 3rd Rock from the Sun Me-Too Mystery Movie 1:00 1:30 Leave It To Beaver 3rd Rock from the Sun 1:30 2:00 I Dream Of Jeannie Roseanne 2:00 2:30 Barney Miller Roseanne Me-Too Mystery Movie 2:30 3:00 Married with Children Gilligan's Island 3:00 3:30 Gilligan's Island Gilligan's Island 3:30 4:00 Roseanne The Munsters Ellery Queen 4:00 4:30 Roseanne The Munsters 4:30 5:00 The Nanny Leave It To Beaver Kojak 5:00 5:30 The Nanny Leave It To Beaver 5:30 6:00 Bewitched Bewitched Hardcastle & McCormick 6:00 6:30 Bewitched I Dream Of Jeannie 6:30 7:00 The Rifleman Stooge-a-palooza Sponsored 7:00 7:30 The Rifleman Sponsored 7:30 8:00 Star Trek: The Original Series Sponsored 8:00 8:30 Sponsored 8:30 9:00 Star Trek: The Next Generation Dragnet Alfred Hitchcock Presents 9:00 9:30 Dragnet Alfred Hitchcock Presents 9:30 10:00 Good Times The Rockford Files Night Gallery 10:00 10:30 All in the Family Night Gallery 10:30 11:00 Frasier T.J. -

Race, Class, and Rosey the Robot: Critical Study of the Jetsons

Race, Class, and Rosey the Robot: Critical Study of The Jetsons ERIN BURRELL The Jetsons is an animated sitcom representing a middle-class patriarchal family set in space in the year 2062. Following in the footsteps of family-friendly viewing such as Leave it to Beaver (1957-1963) and Hanna-Barbera’s own The Flintstones (1960-1966), The Jetsons offered a futuristic take on a near-perfect nuclear family. The Jetsons centers on a family headed by a “male breadwinner” and “Happy housewife heroine” that Betty Friedan credits to creators of women’s media in the 1950s and 60s (23). Packed with conservative white American perspectives and values, the show is set in the suburbs of intergalactic Orbit City and features husband George, wife Jane, teenage daughter Judy, and prodigy son Elroy (Coyle and Mesker 15). The cast is complemented by secondary characters that include George’s boss Cosmo Spacely, the owner of Spacely Sprockets, and Rosey the robot maid. The only element that seemed to be missing from the earliest episodes was a family pet, which was rectified with the addition of Astro the dog early in the first season (“The coming of Astro”). The first season (S1) aired on Sunday nights September 1962 - March 1963, (Coyle and Mesker) and was one of the first shows to debut in color on ABC (Jay). Despite early cancellation the show landed deeply in the pop culture cannon through syndication and experienced renewed interest when it was brought back in the 1980s for two additional seasons (S2-3). Today, The Jetsons continues to reach new audiences with video and digital releases serving to revitalize the program. -

Orientalism in I Dream of Jeannie

APPROVAL PAGE FOR GRADUATE THESIS OR PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF REQUIREMENTS FOR DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS AT CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, LOS ANGELES BY Stephanie Abraham Candidate Interdisciplinary Studies: Cultural Studies Field of Concentration TITLE: HOLLYWOOD’S HAREM HOUSEWIFE: ORIENTALISM IN I DREAM OF JEANNIE APPROVED: Dr. Steven Classen Faculty Member Signature Dr. Dionne Espinoza Faculty Member Signature Dr. John Ramirez Faculty Member Signature Dr. Alan Muchlinski Department Chairperson Signature DATE: 06/07/06 HOLLYWOOD’S HAREM HOUSEWIFE: ORIENTALISM IN I DREAM OF JEANNIE A Thesis Presented to The Faculties of the Departments of Chicana/o Studies, Communication Studies, and Sociology California State University, Los Angeles In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Stephanie Abraham June 2006 © 2006 Stephanie Abraham ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project would not have been possible without the love, support, and patience of so many people in my academic and personal communities, who figured out how to support me even when overwhelmed by their own responsibilities. My expectations of graduate school have been surpassed at California State University, Los Angeles. I have encountered mentors who have greatly impacted my life. I have had the great fortune of spending hours talking and laughing with my thesis advisor, Dr. Steven Classen. He listens and advises and is not afraid to let out his inner-cheerleader to encourage his overworked and underpaid graduate students. He is an excellent professor and mentor. I am also significantly indebted to Dr. Dionne Espinoza, who lets it slide that I call her “dude,” and consistently challenges me to take my scholarship, my dreams, and myself seriously. -

Page 1 East SATURDAY SUNDAY West 5:00 AM I DREAM OF

Effective June 29th, 2020 East MONDAY thru FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY West 5:00 AM GROWING PAINS I DREAM OF JEANNIE THREE'S A CROWD 2:00 AM 5:30 AM GROWING PAINS I DREAM OF JEANNIE THE ROPERS 2:30 AM 6:00 AM THE PARTRIDGE FAMILY BEWITCHED LOTSA LUCK 3:00 AM 6:30 AM THE PARTRIDGE FAMILY BEWITCHED THE PAUL LYNDE SHOW 3:30 AM 7:00 AM THE JOEY BISHOP SHOW MORK AND MINDY SOAP 4:00 AM 7:30 AM THE JOEY BISHOP SHOW MORK AND MINDY SOAP 4:30 AM 8:00 AM THE BURNS AND ALLEN SHOW SABRINA/TEENAGE WITCH BENSON 5:00 AM 8:30 AM THE BURNS AND ALLEN SHOW SABRINA/TEENAGE WITCH BENSON 5:30 AM 9:00 AM FATHER KNOWS BEST JOURNEY WITH... (E/I) ARCHIE BUNKER'S PLACE 6:00 AM 9:30 AM FATHER KNOWS BEST WILDLIFE DOCS (E/I) ARCHIE BUNKER'S PLACE 6:30 AM 10:00 AM DENNIS THE MENACE OCEAN MYSTERIES (E/I) MAUDE 7:00 AM 10:30 AM DENNIS THE MENACE OCEAN MYSTERIES (E/I) MAUDE 7:30 AM 11:00 AM HAZEL OUTBACK ADV. (E/I) THREE'S COMPANY 8:00 AM 11:30 AM HAZEL DID I MENTION... (E/I) THREE'S COMPANY 8:30 AM 12:00 PM THAT GIRL DIFF'RENT STROKES DIFF'RENT STROKES 9:00 AM 12:30 PM THAT GIRL DIFF'RENT STROKES DIFF'RENT STROKES 9:30 AM 1:00 PM I DREAM OF JEANNIE THE FACTS OF LIFE THE FACTS OF LIFE 10:00 AM 1:30 PM I DREAM OF JEANNIE THE FACTS OF LIFE THE FACTS OF LIFE 10:30 AM 2:00 PM BEWITCHED GIMME A BREAK GIMME A BREAK 11:00 AM 2:30 PM BEWITCHED GIMME A BREAK GIMME A BREAK 11:30 AM 3:00 PM THE FACTS OF LIFE WEBSTER WEBSTER 12:00 PM 3:30 PM THE FACTS OF LIFE WEBSTER WEBSTER 12:30 PM 4:00 PM DIFF'RENT STROKES 227 227 1:00 PM 4:30 PM DIFF'RENT STROKES 227 227 1:30 PM 5:00 PM GIMME A BREAK -

Marapr Newsletter 2007

Mar / Apr 2007 Vol. 8 / Issue 2 Helping You Connect to the World about the book and about the process of getting a book self-published. Gale Virtual Reference Library Always open Always available A very informative and lively question and answer ses- The future is now, so imagine an on the link and type in your li- sion followed. When asked authoritative online reference brary card number. if she was going to continue library that is available any time writing, Jill replied that she of the day – and it’s always wait- Once you have logged in, you can was. In fact, she is now at ing for you, not the other way perform a simple Basic Search work on the second book in around. Welcome to Gale Virtual using onscreen prompts and pull- her medical mystery series. Reference Library (GVRL), a down menus. This search offers It will focus on HMOs. three different search options: F irst-time author, Dr. Jill new way to conduct research that Vosler, unveiled her medical allows the user to locate difficult - Keyword (which searches the first 50 words of the article, selected mystery thriller, Lethal Lar- to-find material, thereby bringing ceny, at the Eaton Library reference to a whole new level. subject terms from the book’s index, and the article title), Docu- on March 6. Many people The Gale Virtual Reference Library ment Title and Entire Document. came to purchase the book is a collection of electronic refer- Advanced Search offers additional and get it autographed by ence books (or eBooks) that offer search options – full text, image Preble County’s latest celeb- a variety of subjects and topics. -

For Immediate Release

‘ALWAYS & FOREVER’ CAST BIOS BARBARA EDEN (Mary Anderson) – Barbara Eden, everyone’s favorite ‘Jeannie,’ is one of America’s most endearing and enduring stars. Her NBC series, “I Dream of Jeannie,” has been airing globally for more than three decades and is currently seen on the TV Land cable network 14 times weekly and in syndication throughout the world. In April, Eden went on the road, hosting productions of “Ballroom with a Twist,” the new ground-breaking show that stars rotating celebrity emcees and dancers from “Dancing with the Stars.” She also guest-starred in a recurring role on Lifetime’s popular “Army Wives” series and, just before that, essayed a guest star role on ABC’s “George Lopez.” She recently taped interviews with Sean Hannity on “Hannity” and with Bill O’Reilly on “The O’Reilly Factor,” both on Fox, on “Martha Stewart,” and with “Good Morning America” and “The View” on ABC. Returning to the theater, Eden toured the country with Hal Linden, starring in A.R. Gurney’s Love Letters. Just before Love Letters, she played to SRO audiences for three seasons, headlining a continuing national tour of Neil Simon’s female version of The Odd Couple. Eden, who has been honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, was named by People Magazine as one of America’s Greatest Pop Culture Icons, and she was inducted into the California Broadcasters Association’s Hall of Fame, receiving the Life Achievement Award for on- air excellence through the years. At the national TV Land Awards show, Eden was awarded the Lifetime Achievement -

Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. in Re

Electronically Filed Docket: 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD (2010-2013) Filing Date: 12/29/2017 03:41:40 PM EST Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. In re DISTRIBUTION OF CABLE ROYALTY FUNDS CONSOLIDATED DOCKET NO. 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD In re (2010-13) DISTRIBUTION OF SATELLITE ROYALTY FUNDS WRITTEN DIRECT STATEMENT REGARDING DISTRIBUTION METHODOLOGIES OF THE MPAA-REPRESENTED PROGRAM SUPPLIERS 2010-2013 SATELLITE ROYALTY YEARS VOLUME I OF II WRITTEN TESTIMONY AND EXHIBITS Gregory O. Olaniran D.C. Bar No. 455784 Lucy Holmes Plovnick D.C. Bar No. 488752 Alesha M. Dominique D.C. Bar No. 990311 Mitchell Silberberg & Knupp LLP 1818 N Street NW, 8th Floor Washington, DC 20036 (202) 355-7917 (Telephone) (202) 355-7887 (Facsimile) [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for MPAA-Represented Program Suppliers December 29, 2017 Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. In re DISTRIBUTION OF CABLE ROYALTY FUNDS CONSOLIDATED DOCKET NO. 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD In re (2010-13) DISTRIBUTION OF SATELLITE ROYALTY FUNDS WRITTEN DIRECT STATEMENT REGARDING DISTRIBUTION METHODOLOGIES OF MPAA-REPRESENTED PROGRAM SUPPLIERS FOR 2010-2013 SATELLITE ROYALTY YEARS The Motion Picture Association of America, Inc. (“MPAA”), its member companies and other producers and/or distributors of syndicated series, movies, specials, and non-team sports broadcast by television stations who have agreed to representation by MPAA (“MPAA-represented Program Suppliers”),1 in accordance with the procedural schedule set forth in Appendix A to the December 22, 2017 Order Consolidating Proceedings And Reinstating Case Schedule issued by the Copyright Royalty Judges (“Judges”), hereby submit its Written Direct Statement Regarding Distribution Methodologies (“WDS-D”) for the 2010-2013 satellite royalty years2 in the consolidated 1 Lists of MPAA-represented Program Suppliers for each of the satellite royalty years at issue in this consolidated proceeding are included as Appendix A to the Written Direct Testimony of Jane Saunders. -

Barbara Eden–TV Treasure

Barbara Eden in her study at home, snuggling with her labradoodle Djinn Djinn. By Tobi Schwartz-Cassell Barbara TSC: I have to ask. On I Dream of Jeannie, was that your real hair? BE: (She laughs) Oh boy. I had add-ons. The ponytail itself was quite a construction. It had to stick through the hat and come out. It was pinned on my head like a hat. The ponytail was on a buckram base. TSC: Your favorite episode of I Dream of Jeannie is the pilot. TV Treasure BE: Yes, it is. Gene Nelson did a wonderful Eden job of directing it and of laying down the be nameless, but who wouldn’t even rules for what the show would be from year speak to me on the set because she to year. You have to have rules. It’s like a was very upset that I didn’t look older Constitution. And he did a beautiful job of than I was. I was very young then. And, developing it in that one episode. after all, they cast me in the part! So I was TSC: And your second favorite? a little gun-shy with the next two shows I BE: Well, I enjoyed doing the wedding and did. But they couldn’t have been nicer—both I enjoyed seeing it, but I thought it was a those women—but Lucy in particular. I went mistake to have us married. in there deciding I was just going to do my TSC: Why? This is it! The only remain- lines, do my part and not worry about what Because they should never have married.