Race, Class, and Rosey the Robot: Critical Study of the Jetsons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here Comes Television

September 1997 Vol. 2 No.6 HereHere ComesComes TelevisionTelevision FallFall TVTV PrPrevieweview France’France’ss ExpandingExpanding ChannelsChannels SIGGRAPHSIGGRAPH ReviewReview KorKorea’ea’ss BoomBoom DinnerDinner withwith MTV’MTV’ss AbbyAbby TTerkuhleerkuhle andand CTW’CTW’ss ArleneArlene SherShermanman Table of Contents September 1997 Vol. 2, . No. 6 4 Editor’s Notebook Aah, television, our old friend. What madness the power of a child with a remote control instills in us... 6 Letters: [email protected] TELEVISION 8 A Conversation With:Arlene Sherman and Abby Terkuhle Mo Willems hosts a conversation over dinner with CTW’s Arlene Sherman and MTV’s Abby Terkuhle. What does this unlikely duo have in common? More than you would think! 15 CTW and MTV: Shorts of Influence The impact that CTW and MTV has had on one another, the industry and beyond is the subject of Chris Robinson’s in-depth investigation. 21 Tooning in the Fall Season A new splash of fresh programming is soon to hit the airwaves. In this pivotal year of FCC rulings and vertical integration, let’s see what has been produced. 26 Saturday Morning Bonanza:The New Crop for the Kiddies The incurable, couch potato Martha Day decides what she’s going to watch on Saturday mornings in the U.S. 29 Mushrooms After the Rain: France’s Children’s Channels As a crop of new children’s channels springs up in France, Marie-Agnès Bruneau depicts the new play- ers, in both the satellite and cable arenas, during these tumultuous times. A fierce competition is about to begin... 33 The Korean Animation Explosion Milt Vallas reports on Korea’s growth from humble beginnings to big business. -

In This Episode of the Flintstones, the Main Characters Are Shown to Seek Martial Arts Lessons

In this episode of the Flintstones, the main characters are shown to seek martial arts lessons. The judo master in the scene is depicted as a Japanese man who wears a sinister-looking smile throughout the scene. He offers the characters lessons at supposedly good prices. As he rattles off the offers by ensuring them that they could get "silver medal lessons" for "[a] big bargain, big bargain" and "for a few more measly dollars ... gold medals, diamond medals...," his pronunciations are exaggeratedly shown to be wrong by a mix up between r's and l's and by an obvious difference in the emphasis on syllables. The man's speech is set apart from the other characters' by juxtaposing his differently accented words to the others' SAE pronunciation. Also, the Flintstones and their friends bowed while imitating his accent as if attempting to fit that man's mannerisms. However, this can be seen as making light of the man's characteristics and manners as if they are silly. In this scene, the judo master portrays prevalent stereotypes about Asians. The man's inability to enunciate r's and l's reflect the struggle that many people face in differentiating between r's and l's in English because their native tongues do not make the same distinction. More importantly, the judo master's speech is used to indicate a lack of intelligence, as evidence by Fred's comment, "What does 'et cetera, et cetera' mean in Japanese? Sucker?" which is followed by Barney's response in a tone mocking the Japanese man's, "Oh, that's for sure!" Furthermore, prior to that, Fred had thrown in an unintelligible word in an attempt to imitate the man's Japanese accent. -

Retrofuture Hauntings on the Jetsons

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Queens College 2020 No Longer, Not Yet: Retrofuture Hauntings on The Jetsons Stefano Morello CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/qc_pubs/446 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] de genere Rivista di studi letterari, postcoloniali e di genere Journal of Literary, Postcolonial and Gender Studies http://www.degenere-journal.it/ @ Edizioni Labrys -- all rights reserved ISSN 2465-2415 No Longer, Not Yet: Retrofuture Hauntings on The Jetsons Stefano Morello The Graduate Center, City University of New York [email protected] From Back to the Future to The Wonder Years, from Peggy Sue Got Married to The Stray Cats’ records – 1980s youth culture abounds with what Michael D. Dwyer has called “pop nostalgia,” a set of critical affective responses to representations of previous eras used to remake the present or to imagine corrective alternatives to it. Longings for the Fifties, Dwyer observes, were especially key to America’s self-fashioning during the Reagan era (2015). Moving from these premises, I turn to anachronisms, aesthetic resonances, and intertextual references that point to, as Mark Fisher would have it, both a lost past and lost futures (Fisher 2014, 2-29) in the episodes of the Hanna-Barbera animated series The Jetsons produced for syndication between 1985 and 1987. A product of Cold War discourse and the early days of the Space Age, the series is characterized by a bidirectional rhetoric: if its setting emphasizes the empowering and alienating effects of technological advancement, its characters and its retrofuture aesthetics root the show in a recognizable and desirable all-American past. -

The Flintstones (1960-1966), About a “Modern Stone-Age Family,” Was The

Columbia Pictures) to develop a prime-time animated series. They worked out the concept of parodying current situation comedies, especially The Honeymooners and Father Knows Best, with the twist of setting them in a different historical era. Cartoonists Dan Gordon and Bill Benedict had the idea to use a Stone Age setting (although the Fleischer Studios pro- duced a similar series of Stone Age Cartoons back in 1940). The concept was bought by ABC, and premiered Sept. 30, 1960. Voiced by Alan Reed, Jr. (Fred Flintstone), Mel Blanc (Barney Rubble), Jean VanderPyl (Wilma Flintstone) and veteran actress Bea Benaderet (Betty Rubble), The Flintstones finished the season in the Nielsen ratings’ top 20, and won a number of industry awards, including the Golden Globe, and an [email protected] Emmy nomination for best comedy series of 1960-61. A clear appeal of the series lays in its parody of sitcom for- mula plots, and there are elements of satire in the way modern consumer conveniences are turned into sight gags. One of the show’s favorite gags was to have cameos by Stone Age versions of modern celebrities (Ann Margrock, Stony Curtis, etc.). The most popular gimmick was Wilma’s pregnancy, ending with the February 1963 “birth” of their little girl, Pebbles. The next season the Rubbles adopted Bamm-Bamm, a little boy of incredible strength and a one- word vocabulary. By the fifth and sixth seasons, the show began to use more storylines aimed at kids, with new neighbors the Grue- somes (a spin on The Munsters and The Addams Family), and magical space alien The Great Gazoo (Harvey Korman). -

Teachers Guide

Teachers Guide Exhibit partially funded by: and 2006 Cartoon Network. All rights reserved. TEACHERS GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE 3 EXHIBIT OVERVIEW 4 CORRELATION TO EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS 9 EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS CHARTS 11 EXHIBIT EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES 13 BACKGROUND INFORMATION FOR TEACHERS 15 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS 23 CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES • BUILD YOUR OWN ZOETROPE 26 • PLAN OF ACTION 33 • SEEING SPOTS 36 • FOOLING THE BRAIN 43 ACTIVE LEARNING LOG • WITH ANSWERS 51 • WITHOUT ANSWERS 55 GLOSSARY 58 BIBLIOGRAPHY 59 This guide was developed at OMSI in conjunction with Animation, an OMSI exhibit. 2006 Oregon Museum of Science and Industry Animation was developed by the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry in collaboration with Cartoon Network and partially funded by The Paul G. Allen Family Foundation. and 2006 Cartoon Network. All rights reserved. Animation Teachers Guide 2 © OMSI 2006 HOW TO USE THIS TEACHER’S GUIDE The Teacher’s Guide to Animation has been written for teachers bringing students to see the Animation exhibit. These materials have been developed as a resource for the educator to use in the classroom before and after the museum visit, and to enhance the visit itself. There is background information, several classroom activities, and the Active Learning Log – an open-ended worksheet students can fill out while exploring the exhibit. Animation web site: The exhibit website, www.omsi.edu/visit/featured/animationsite/index.cfm, features the Animation Teacher’s Guide, online activities, and additional resources. Animation Teachers Guide 3 © OMSI 2006 EXHIBIT OVERVIEW Animation is a 6,000 square-foot, highly interactive traveling exhibition that brings together art, math, science and technology by exploring the exciting world of animation. -

“I DREAM of JEANNIE” STAR RETURNS to SPACE COAST Barbara Eden to Perform at 50Th Anniversary of Iconic TV Series

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE “I DREAM OF JEANNIE” STAR RETURNS TO SPACE COAST Barbara Eden to Perform at 50th Anniversary of Iconic TV Series COCOA BEACH, FL – September 3, 2015. Barbara Eden, the star of the 1960s sitcom, “I Dream of Jeannie,” returns to Florida’s Space Coast on Sunday, October 25 for the 50th anniversary of the premiere of the iconic show set in Cocoa Beach, FL. “On the Magic Carpet with Barbara Eden” will feature Ms. Eden and “Entertainment Tonight” and Showtime movie reporter Bill Harris on stage at the Scott Center Auditorium on the campus of Holy Trinity Episcopal Academy in Melbourne. The performance will take guests back into Jeannie’s Magic Bottle in a fun-filled evening of storytelling and the screening of rare and never before seen film clips featuring Barbara Eden and such stars as Elvis Presley, Paul Newman, Frank Sinatra, Lucille Ball, Bob Hope, and her “I Dream of Jeannie” co-star Larry Hagman. The show will also include a lively Q & A session between Ms. Eden and the audience, in addition to a limited Meet & Greet reception following the performance. “The people of Cocoa Beach have always been so gracious and welcoming to me,” said Eden. “Even though we never actually filmed the show there, we have spent a lot of time on the Space Coast. It seems like a second home to me, and I am very excited to go back there and see so many familiar and friendly faces.” The show and Ms. Eden’s appearance are largely made possible due in part to the support of SCB Marketing and the Brevard County Tourism Development Council's Special Event Marketing Grant Program and the Space Coast Office of Tourism. -

A Dpics-Ii Analysis of Parent-Child Interactions

WHAT ARE YOUR CHILDREN WATCHING? A DPICS-II ANALYSIS OF PARENT-CHILD INTERACTIONS IN TELEVISION CARTOONS Except where reference is made to the work of others, the work described in this dissertation is my own or was done in collaboration with my advisory committee. This dissertation does not include proprietary or classified information. _______________________ Lori Jean Klinger Certificate of Approval: ________________________ ________________________ Steven K. Shapiro Elizabeth V. Brestan, Chair Associate Professor Associate Professor Psychology Psychology ________________________ ________________________ James F. McCoy Elaina M. Frieda Associate Professor Assistant Professor Psychology Experimental Psychology _________________________ Joe F. Pittman Interim Dean Graduate School WHAT ARE YOUR CHILDREN WATCHING? A DPICS-II ANALYSIS OF PARENT-CHILD INTERACTIONS IN TELEVISION CARTOONS Lori Jean Klinger A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama December 15, 2006 WHAT ARE YOUR CHILDREN WATCHING? A DPICS-II ANALYSIS OF PARENT-CHILD INTERACTIONS IN TELEVISION CARTOONS Lori Jean Klinger Permission is granted to Auburn University to make copies of this dissertation at its discretion, upon request of individuals or institutions and at their expense. The author reserves all publication rights. ________________________ Signature of Author ________________________ Date of Graduation iii VITA Lori Jean Klinger, daughter of Chester Klinger and JoAnn (Fetterolf) Bachrach, was born October 24, 1965, in Ashland, Pennsylvania. She graduated from Owen J. Roberts High School as Valedictorian in 1984. She graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1988 and served as a Military Police Officer in the United States Army until 1992. -

I Dream of Jeannie Trivia Quiz

I DREAM OF JEANNIE TRIVIA QUIZ ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> In what year did the TV sitcom "I Dream of Jeannie" first air? a. 1965 b. 1975 c. 1972 d. 1970 2> What was the name of Anthony's best friend? a. George b. Roger c. Harvey d. Steve 3> What was Anthony Nelson's rank? a. General b. Colonel c. Major d. Lieutenant 4> What kind of craft was Major Nelson in when he crashed into the ocean? a. A jet plane b. A helicopter c. A glider d. A capsule 5> Where did Anthony Nelson live? a. Palm Springs b. Kissimmee c. Cocoa Beach d. Tampa 6> When casting a spell, what does Jeannie do? a. Twitch her nose b. Blink c. Chant d. Clap her hands 7> What is the name of the psychiatrist? a. Dr. Bellows b. Dr. Roberts c. Dr. Johnson d. Dr. Wilson 8> How old is Jeannie? a. 2,000 Years Old b. 500 Years Old c. 7,000 Years Old d. 10,000 Years Old 9> In which episode does Anthony's best friend discover that he has a Jeannie? a. The Moving Finger b. The Richest Astronaut in the Whole Wide World c. Guess What Happened on the Way to the Moon? d. The Americanization of Jeannie 10> When is Jeannie's birthday? a. May23 b. August 27 c. October 31 d. April 1 11> What is Anthony's address? a. 100 Date Avenue b. 1020 Palm Drive c. 776 Sunset Avenue d. 592 Oceanside Drive 12> What sport is Anthony supposed to play with General Peterson? a. -

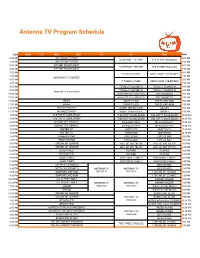

Antenna TV Program Schedule

Antenna TV Program Schedule East MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN West 5:00 AM BACHELOR FATHER 2:00 AM SUSPENSE THEATRE THE THREE STOOGES 5:30 AM BACHELOR FATHER 2:30 AM 6:00 AM FATHER KNOWS BEST 3:00 AM SUSPENSE THEATRE THE THREE STOOGES 6:30 AM FATHER KNOWS BEST 3:30 AM 7:00 AM 4:00 AM IT TAKES A THIEF HERE COME THE BRIDES 7:30 AM 4:30 AM ANTENNA TV THEATER 8:00 AM 5:00 AM IT TAKES A THIEF HERE COME THE BRIDES 8:30 AM 5:30 AM 9:00 AM TOTALLY TOONED IN TOTALLY TOONED IN 6:00 AM 9:30 AM TOTALLY TOONED IN TOTALLY TOONED IN 6:30 AM ANTENNA TV THEATER 10:00 AM ANIMAL RESCUE CLASSICS (E/I) THE MONKEES 7:00 AM 10:30 AM ANIMAL RESCUE CLASSICS (E/I) THE MONKEES 7:30 AM 11:00 AM HAZEL SWAP TV (E/I) THE FLYING NUN 8:00 AM 11:30 AM HAZEL SWAP TV (E/I) THE FLYING NUN 8:30 AM 12:00 PM MCHALE'S NAVY WORD TRAVELS (E/I) GIDGET 9:00 AM 12:30 PM MCHALE'S NAVY WORD TRAVELS (E/I) GIDGET 9:30 AM 1:00 PM THE PATTY DUKE SHOW THE PATTY DUKE SHOW THE PATTY DUKE SHOW 10:00 AM 1:30 PM THE PATTY DUKE SHOW THE PATTY DUKE SHOW THE PATTY DUKE SHOW 10:30 AM 2:00 PM DENNIS THE MENACE MCHALE'S NAVY MCHALE'S NAVY 11:00 AM 2:30 PM DENNIS THE MENACE MCHALE'S NAVY MCHALE'S NAVY 11:30 AM 3:00 PM MISTER ED MISTER ED MISTER ED 12:00 PM 3:30 PM MISTER ED MISTER ED MISTER ED 12:30 PM 4:00 PM GREEN ACRES CIRCUS BOY CIRCUS BOY 1:00 PM 4:30 PM GREEN ACRES CIRCUS BOY CIRCUS BOY 1:30 PM 5:00 PM I DREAM OF JEANNIE ADV. -

INSTITUTION Congress of the US, Washington, DC. House Committee

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 303 136 IR 013 589 TITLE Commercialization of Children's Television. Hearings on H.R. 3288, H.R. 3966, and H.R. 4125: Bills To Require the FCC To Reinstate Restrictions on Advertising during Children's Television, To Enforce the Obligation of Broadcasters To Meet the Educational Needs of the Child Audience, and for Other Purposes, before the Subcommittee on Telecommunications and Finance of the Committee on Energy and Commerce, House of Representatives, One Hundredth Congress (September 15, 1987 and March 17, 1988). INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, DC. House Committee on Energy and Commerce. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 354p.; Serial No. 100-93. Portions contain small print. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. PUB TYPE Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) -- Viewpoints (120) -- Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Advertising; *Childrens Television; *Commercial Television; *Federal Legislation; Hearings; Policy Formation; *Programing (Broadcast); *Television Commercials; Television Research; Toys IDENTIFIERS Congress 100th; Federal Communications Commission ABSTRACT This report provides transcripts of two hearings held 6 months apart before a subcommittee of the House of Representatives on three bills which would require the Federal Communications Commission to reinstate restrictions on advertising on children's television programs. The texts of the bills under consideration, H.R. 3288, H.R. 3966, and H.R. 4125 are also provided. Testimony and statements were presented by:(1) Representative Terry L. Bruce of Illinois; (2) Peggy Charren, Action for Children's Television; (3) Robert Chase, National Education Association; (4) John Claster, Claster Television; (5) William Dietz, Tufts New England Medical Center; (6) Wallace Jorgenson, National Association of Broadcasters; (7) Dale L. -

Looking Back at the Creative Process

IATSE LOCAL 839 MAGAZINE SPRING 2020 ISSUE NO. 9 THE ANIMATION GUILD QUARTERLY SCOOBY-DOO / TESTING PRACTICES LOOKING BACK AT THE CREATIVE PROCESS SPRING 2020 “HAS ALL THE MAKINGS OF A CLASSIC.” TIME OUT NEW YORK “A GAMECHANGER”. INDIEWIRE NETFLIXGUILDS.COM KEYFRAME QUARTERLY MAGAZINE OF THE ANIMATION GUILD, COVER 2 REVISION 1 NETFLIX: KLAUS PUB DATE: 01/30/20 TRIM: 8.5” X 10.875” BLEED: 8.75” X 11.125” ISSUE 09 CONTENTS 12 FRAME X FRAME 42 TRIBUTE 46 FRAME X FRAME Kickstarting a Honoring those personal project who have passed 6 FROM THE 14 AFTER HOURS 44 CALENDAR FEATURES PRESIDENT Introducing The Blanketeers 46 FINAL NOTE 20 EXPANDING THE Remembering 9 EDITOR’S FIBER UNIVERSE Disney, the man NOTE 16 THE LOCAL In Trolls World Tour, Poppy MPI primer, and her crew leave their felted Staff spotlight 11 ART & CRAFT homes to meet troll tribes Tiffany Ford’s from different regions of the color blocks kingdom in an effort to thwart Queen Barb and King Thrash from destroying all the other 28 styles of music. Hitting the road gave the filmmakers an opportunity to invent worlds from the perspective of new fabrics and fibers. 28 HIRING HUMANELY Supervisors and directors in the LA animation industry discuss hiring practices, testing, and the realities of trying to staff a show ethically. 34 ZOINKS! SCOOBY-DOO TURNS 50 20 The original series has been followed by more than a dozen rebooted series and movies, and through it all, artists and animators made sure that “those meddling kids” and a cowardly canine continued to unmask villains. -

Speed and Security

SPEED AND SECURITY KATHRYN E. BOUSKILL | SEIFU CHONDE | WILLIAM WELSER IV Perspective EXPERT INSIGHTS ON A TIMELY POLICY ISSUE C O R P O R A T I O N Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions.html. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. R® is a registered trademark. For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/PE274. © Copyright 2018 RAND Corporation cross the world, there is a profound sense that life is which speed is just one particular force acting upon the landscape of speeding up, and the faster life gets, the more we have global risk and security. to adjust our norms to keep pace. In much the same The Perspective first reviews the concept of speed and the way that the streetcar once outpaced the horse and general interdisciplinary approach taken to explore the possibilities Abuggy (see Figure 1), the world finds itself in a transitional phase to of a faster future. A central thread is the hypothesis that this itera- greater speed.