Pursuit of Faith: “Navigating Ethics and Self-Referential Documentary”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Same Breath

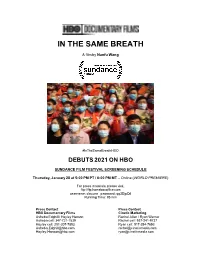

IN THE SAME BREATH A film by Nanfu Wang #InTheSameBreathHBO DEBUTS 2021 ON HBO SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL SCREENING SCHEDULE Thursday, January 28 at 5:00 PM PT / 6:00 PM MT – Online (WORLD PREMIERE) For press materials, please visit: ftp://ftp.homeboxoffice.com username: documr password: qq3DjpQ4 Running Time: 95 min Press Contact Press Contact HBO Documentary Films Cinetic Marketing Asheba Edghill / Hayley Hanson Rachel Allen / Ryan Werner Asheba cell: 347-721-1539 Rachel cell: 937-241-9737 Hayley cell: 201-207-7853 Ryan cell: 917-254-7653 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] LOGLINE Nanfu Wang's deeply personal IN THE SAME BREATH recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. SHORT SYNOPSIS IN THE SAME BREATH, directed by Nanfu Wang (“One Child Nation”), recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. In a deeply personal approach, Wang, who was born in China and now lives in the United States, explores the parallel campaigns of misinformation waged by leadership and the devastating impact on citizens of both countries. Emotional first-hand accounts and startling, on-the-ground footage weave a revelatory picture of cover-ups and misinformation while also highlighting the strength and resilience of the healthcare workers, activists and family members who risked everything to communicate the truth. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT I spent a lot of my childhood in hospitals taking care of my father, who had rheumatic heart disease. -

Kennedy Matthew C 2016 Ma

BLIND DATE MATTHEW KENNEDY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN FILM YORK UNIVERISTY TORONTO, ONTARIO June 2016 © Matthew Kennedy, 2016 Abstract Blind Date is a documentary film about a young woman from rural China named Chun Cao Zhao who is pressured into marriage through a tradition known as “blind dating.” The film begins in Guangzhou, a sprawling metropolis in Southern China, where she has been living for the past ten years, and is just days away from returning home for her wedding. As she slowly says goodbye to city life, the life she wants to keep, she reveals to the camera her feelings toward her fiancé, her thoughts on the impending wedding and her own struggles to find a boyfriend. As the film follows her back home we intimately witness the sacrifices she is forced to make in order to appease her parents and the greater instrument of Chinese culture. The film examines and contrasts contemporary China with traditional China and displays the varying roles of each gender in both rural and urban settings. The film concludes with her arranged marriage and a short follow-up with her new husband six months after the wedding. ii Acknowledgements Throughout the entire process of making this film I have several people to which I owe a tremendous amount of gratitude. Firstly, to my supervisor Barbara Evans, making this film was a long journey and it could not have been done without her patience, encouragement and unwavering support. -

A Canadian Perspective on the International Film Festival

NEGOTIATING VALUE: A CANADIAN PERSPECTIVE ON THE INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL by Diane Louise Burgess M.A., University ofBritish Columbia, 2000 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the School ofCommunication © Diane Louise Burgess 2008 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2008 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or by other means, without permission ofthe author. APPROVAL NAME Diane Louise Burgess DEGREE PhD TITLE OF DISSERTATION: Negotiating Value: A Canadian Perspective on the International Film Festival EXAMINING COMMITTEE: CHAIR: Barry Truax, Professor Catherine Murray Senior Supervisor Professor, School of Communication Zoe Druick Supervisor Associate Professor, School of Communication Alison Beale Supervisor Professor, School of Communication Stuart Poyntz, Internal Examiner Assistant Professor, School of Communication Charles R Acland, Professor, Communication Studies Concordia University DATE: September 18, 2008 11 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the "Institutional Repository" link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

Minding the Gap : a Rhetorical History of the Achievement

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Minding the gap : a rhetorical history of the achievement gap Laura Elizabeth Jones Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Laura Elizabeth, "Minding the gap : a rhetorical history of the achievement gap" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3633. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3633 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. MINDING THE GAP: A RHETORICAL HISTORY OF THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Laura Jones B.S., University of Colorado, 1995 M.S., Louisiana State University, 2010 August 2013 To the students of Glen Oaks, Broadmoor, SciAcademy, McDonough 35, and Bard Early College High Schools in Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana ii Acknowledgements I am happily indebted to more people than I can name, particularly members of the Baton Rouge and New Orleans communities, where countless students, parents, faculty members and school leaders have taught and inspired me since I arrived here in 2000. I am happy to call this complicated and deeply beautiful community my home. -

A Canadian Perspective on the International Film Festival

NEGOTIATING VALUE: A CANADIAN PERSPECTIVE ON THE INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL by Diane Louise Burgess M.A., University ofBritish Columbia, 2000 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the School ofCommunication © Diane Louise Burgess 2008 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2008 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or by other means, without permission ofthe author. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-58719-5 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-58719-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. -

1997 Sundance Film Festival Awards Jurors

1997 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL The 1997 Sundance Film Festival continued to attract crowds, international attention and an appreciative group of alumni fi lmmakers. Many of the Premiere fi lmmakers were returning directors (Errol Morris, Tom DiCillo, Victor Nunez, Gregg Araki, Kevin Smith), whose earlier, sometimes unknown, work had received a warm reception at Sundance. The Piper-Heidsieck tribute to independent vision went to actor/director Tim Robbins, and a major retrospective of the works of German New-Wave giant Rainer Werner Fassbinder was staged, with many of his original actors fl own in for forums. It was a fi tting tribute to both Fassbinder and the Festival and the ways that American independent cinema was indeed becoming international. AWARDS GRAND JURY PRIZE JURY PRIZE IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Documentary—GIRLS LIKE US, directed by Jane C. Wagner and LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY (O SERTÃO DAS MEMÓRIAS), directed by José Araújo Tina DiFeliciantonio SPECIAL JURY AWARD IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Dramatic—SUNDAY, directed by Jonathan Nossiter DEEP CRIMSON, directed by Arturo Ripstein AUDIENCE AWARD JURY PRIZE IN SHORT FILMMAKING Documentary—Paul Monette: THE BRINK OF SUMMER’S END, directed by MAN ABOUT TOWN, directed by Kris Isacsson Monte Bramer Dramatic—HURRICANE, directed by Morgan J. Freeman; and LOVE JONES, HONORABLE MENTIONS IN SHORT FILMMAKING directed by Theodore Witcher (shared) BIRDHOUSE, directed by Richard C. Zimmerman; and SYPHON-GUN, directed by KC Amos FILMMAKERS TROPHY Documentary—LICENSED TO KILL, directed by Arthur Dong Dramatic—IN THE COMPANY OF MEN, directed by Neil LaBute DIRECTING AWARD Documentary—ARTHUR DONG, director of Licensed To Kill Dramatic—MORGAN J. -

Reconfiguring Home Movies in Experimental Cinema Kelsey Haas a Thesis in the Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema

Inherited Images: Reconfiguring Home Movies in Experimental Cinema Kelsey Haas A Thesis in The Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Masters of Art (Film Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada July 2013 © Kelsey Haas, 2013 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Kelsey Haas Entitled: Inherited Images: Reconfiguring Home Movies in Experimental Cinema and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: ______________________________________ Chair Daniel Cross ______________________________________ Examiner Peter Rist ______________________________________ Examiner Rick Hancox ______________________________________ Supervisor Catherine Russell Approved by ______________________________________________________ Luca Caminati Graduate Program Director ______________________________________________________ Catherine Wild Dean of the Faculty of Fine Arts Date ______________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Inherited Images: Reconfiguring Home Movies in Experimental Cinema Kelsey Haas This thesis examines a subset of contemporary experimental filmmakers who incorporate their own home movies into their films and videos. Close analysis of Helen Hill’s Mouseholes (1999), Richard Fung’s Sea in the Blood (2000), Philip Hoffman’s What these Ashes Wanted (2001), and Jay Rosenblatt’s Phantom Limb (2005) reveals tensions between the private and public functions of home movies as well as key differences between the reconfigurations of home movies and the appropriation of found footage. When experimental filmmakers use home movies, it is often a means of confronting issues of memory; also, the filmmakers most often strive to preserve the home movies because of their personal connection to them. -

F. Scott Fitzgerald the Stand

Fiction Songs The Great Gatsby – F. Scott Fitzgerald “Change is Gonna Come” – Sam Cooke The Stand - Stephen King “Oh Holy Night” – Adolph Adam Things Fall Apart – Chinua Achebe “Come as You Are” – Nirvana Brave New World – Aldous Huxley “Paper Tiger” – Beck The Alchemist – Paulo Coelho “Sweet Child O’ Mine” – Guns N Roses Nineteen Eighty Four – George Orwell “Amazing Grace” – John Newton Of Mice and Men – John Steinbeck “Father and Son” – Cat Stevens The Road – Cormac McCarthy “Go or Go Ahead” – Rufus Wainright The Lovely Bones – Alice Sebold “And Justice For All” – Metallica The Fountainhead – Ayn Rand “In My Life” – The Beetles Non-fiction Movies A Brief History of Time – Stephen Hawking The Godfather – Francis Ford Coppola My Life in Art – Konstantin Stanislavsky Magnolia – Paul Thomas Anderson The Singularity is Near – Ray Kurzweil It’s a Wonderful Life – Frank Capra The Tipping Point – Malcolm Gladwell Being John Malkovich – Spike Jonze Bossypants – Tina Fey Life is Beautiful – Roberto Benigni Revelation – John (The One Who Jesus Loved) Gone With the Wind – Victor Fleming The Supernatural Worldview – Cris Putnam Lost in Translation – Sophia Coppola Relativity – Albert Einstein Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind – In Cold Blood – Truman Capote Michel Gondry Exodus – Moses The Sting – George Roy Hill The Little Princess – Walter Lang Children’s Books Documentaries The Giving Tree – Shel Silverstein Grey Gardens – Ellen Hoyde, Albert Maysles The Chronicles of Narnia series– C.S. Lewis The Imposter – Bart Layton Every Amelia Bedelia – Peggy/Herman Parish Hoop Dreams – Steve James Charlotte’s Web – E.B. White Fahrenheit 911 – Michael Moore The Cat in the Hat – Dr. -

HIGHLIGHTS … They Have Created a Public Event You Could No More Cancel Than You Could Cancel Valentine’S Day

2018HIGHLIGHTS … they have created a public event you could no more cancel than you could cancel Valentine’s Day. — Kate Taylor, The Globe and Mail Contents 1 INTRODUCTION NCFD by the numbers • Spotlight on Women • Trailblazers 12 SCREENING EVENTS Interactive Google map • Enhanced events • International events • 2018 communities • RCtv 26 SCREENING PARTNER RESOURCES 30 ONLINE, ON-AIR AND IN-THE-AIR PROGRAMMING 36 BUZZ Promotional video • Media coverage highlights • Social media highlights • Website highlights • Media partnerships 46 TESTIMONIALS 50 SUPPORT REEL CANADA Board of Directors and Advisory Committee • Our Sponsors • Our Partners Introduction “… they have, in five short years, created a public event you could The way Canadians embraced our spotlight on women also showed no more cancel than you could cancel Valentine’s Day.” us that Canadians are not only hungry for homegrown stories, but – Kate Taylor, The Globe and Mail are deeply interested in hearing underrepresented voices, and celebrating them. When the article quoted above was published, that’s when we knew. We don’t expect you, Dear Reader, to take in every detail of this report. But we hope you will browse and enjoy some of the nuggets We knew there was a huge appetite for a cultural celebration that — the individual testimonials, the range of screening venues (and allows us to embrace our own stories, and we knew that Canadians countries!) and the ways in which screening partners made the day are beginning to think of it as a national institution! their own. It’s not very Canadian of us to toot our own horn, but we’re Reflecting on the fifth annual NCFD brings us to one conclusion: incredibly proud of the way National Canadian Film Day (NCFD) celebrating Canada by watching great Canadian films truly matters has grown over the past five years. -

Starz’S €˜America to Me’ Docuseries Explores Race in Schools

Starz’s ‘America to Me’ Docuseries Explores Race in Schools 06.29.2018 Filmmaker Steve James (Hoop Dreams, The Interrupters, Life Itself, Abacus: Small Enough to Jail) spent a year inside suburban Chicago's Oak Park and River Forest High School, exploring the grapple with decades-long racial and educational inequities. America to Me follows students, teachers and administrators at one of the country's highest performing and diverse public schools, digging into many of the stereotypes and challenges that today's teenagers face, and looking at what has succeeded and failed in the quest to achieve racial equality in our educational system. The 10-part series also serves as the launch of a social impact campaign focusing on the issues highlighted in each episode. Starz partnered with series producer Participant Media to encourage candid conversations about racism through a downloadable Community Conversation Toolkit and elevate student voices through a national spoken-word poetry contest. Alongside the release of each new episode, the campaign will also host a high-profile screening event in one city across the country. Over the course of 10 weeks, these 10 events will seed a national dialogue anchored by the series, and kick off activities across the country to inspire students, teachers, parents and community leaders to develop local initiatives that address inequities in their own communities, says Starz. James directed and executive produced the series, along with executive producers Gordon Quinn (The Trials of Muhammad Ali), Betsy Steinberg (Edith+Eddie) and Justine Nagan (Minding the Gap) at his longtime production home, Kartemquin Films. -

Doc Nyc Unveils Influential Short Lists

DOC NYC UNVEILS INFLUENTIAL SHORT LISTS FOR FEATURES & SHORTS PLUS INAUGURAL “WINNER’S CIRCLE” SECTION, LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT SCREENINGS, “40 UNDER 40” LIST AND NEW AWARDS NEW YORK, September 26, 2019 - DOC NYC, America’s largest documentary festival, celebrating its 10th anniversary, announced the lineup for three of its most prestigious sections. Short List: Features and Short List: Shorts each curate a selection of nonfiction films that the festival’s programming team considers to be among the year’s strongest contenders for Oscars and other awards. For the first time, the Short List: Features will vie for juried awards in four categories: Directing, Producing, Cinematography and Editing, and a Best Director prize will also be awarded in the Short List: Shorts section. The festival also announced the launch of a new section, Winner’s Circle, highlighting films that have won top prizes at international festivals, but might fly below the radar of American audiences. Michael Apted and Martin Scorsese, the two recipients of DOC NYC’s previously announced Visionaries Lifetime Achievement Awards, will also have their latest documentary films screened: 63 Up and Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese, respectively. The festival also announced the second year of its 40 Under 40 list of young rising stars in the documentary community, co-presented by Topic Studios. “Today’s announcements of the DOC NYC Short Lists, Winner’s Circle and 40 Under 40 showcase a tremendous breadth and depth of talent,” said festival Artistic Director Thom Powers. “We’re excited to bring New York audiences to some of the year’s best films and showcase the future of the documentary field.” AMPAS members can email [email protected] to register for a Short List Pass to gain free admission to Short List, Winner’s Circle and Lifetime Achievement screenings; as well as to the panel discussions for Short List: Features (Fri, Nov. -

Ratti AP Lang Summer Assignments 2020-2021

Ratti AP Lang Summer Assignments 2020-2021 May 1, 2020 Dear Future Student, Hello, and welcome! I’m so excited that you have chosen to take one of the most stimulating and rewarding classes offered at MCHS. As I’m sure you know, it’s going to be a challenge, but I’ll be with you every step of the way. When we challenge ourselves, we grow. AP Language and Composition is going to help you grow as a reader and a writer, and, I suspect, even as a person. I can say that teaching this class has been a joy as well as a tremendous growth opportunity for me. We are in it together. The summer of 2020 looks like it is going to be challenging, but I have provided these assignments in hopes that you will be able to continue your education in enjoyable and productive ways while you are stuck at home. I have made an effort to include resources and suggestions so that students at all levels of income and technology access can complete the assignments successfully. If you have any difficulty or concern, please contact me as soon as possible. You may reach me by email, Remind, by posting on Teams, or by calling the school at (423) 745-4142. I will make every effort to make sure any student who wants to participate is able to. The biggest part of your work for me will be the Knowledge Builders assignment, a fact-gathering, critical thinking challenge to broaden your knowledge of the world around you.