Lushai Brigade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (APO)

E-Book - 22. Checklist - Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (A.P.O) By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 22. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 8th May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 27 Nos. Date/Year Details of Issue 1 2 1971 - 1980 1 01/12/1954 International Control Commission - Indo-China 2 15/01/1962 United Nations Force - Congo 3 15/01/1965 United Nations Emergency Force - Gaza 4 15/01/1965 International Control Commission - Indo-China 5 02/10/1968 International Control Commission - Indo-China 6 15.01.1971 Army Day 7 01.04.1971 Air Force Day 8 01.04.1971 Army Educational Corps 9 04.12.1972 Navy Day 10 15.10.1973 The Corps of Electrical and Mechanical Engineers 11 15.10.1973 Zojila Day, 7th Light Cavalary 12 08.12.1973 Army Service Corps 13 28.01.1974 Institution of Military Engineers, Corps of Engineers Day 14 16.05.1974 Directorate General Armed Forces Medical Services 15 15.01.1975 Armed Forces School of Nursing 03.11.1976 Winners of PVC-1 : Maj. Somnath Sharma, PVC (1923-1947), 4th Bn. The Kumaon 16 Regiment 17 18.07.1977 Winners of PVC-2: CHM Piru Singh, PVC (1916 - 1948), 6th Bn, The Rajputana Rifles. 18 20.10.1977 Battle Honours of The Madras Sappers Head Quarters Madras Engineer Group & Centre 19 21.11.1977 The Parachute Regiment 20 06.02.1978 Winners of PVC-3: Nk. -

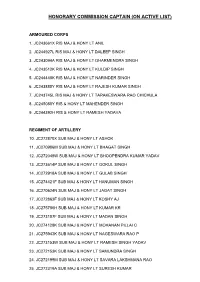

Honorary Commission Captain (On Active List)

HONORARY COMMISSION CAPTAIN (ON ACTIVE LIST) ARMOURED CORPS 1. JC243661X RIS MAJ & HONY LT ANIL 2. JC244927L RIS MAJ & HONY LT DALEEP SINGH 3. JC243094A RIS MAJ & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH 4. JC243512K RIS MAJ & HONY LT KULDIP SINGH 5. JC244448K RIS MAJ & HONY LT NARINDER SINGH 6. JC243880Y RIS MAJ & HONY LT RAJESH KUMAR SINGH 7. JC243745L RIS MAJ & HONY LT TARAKESWARA RAO CHICHULA 8. JC245080Y RIS & HONY LT MAHENDER SINGH 9. JC244392H RIS & HONY LT RAMESH YADAVA REGIMENT OF ARTILLERY 10. JC272870X SUB MAJ & HONY LT ASHOK 11. JC270906M SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHAGAT SINGH 12. JC272049W SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHOOPENDRA KUMAR YADAV 13. JC273614P SUB MAJ & HONY LT GOKUL SINGH 14. JC272918A SUB MAJ & HONY LT GULAB SINGH 15. JC274421F SUB MAJ & HONY LT HANUMAN SINGH 16. JC270624N SUB MAJ & HONY LT JAGAT SINGH 17. JC272863F SUB MAJ & HONY LT KOSHY AJ 18. JC275786H SUB MAJ & HONY LT KUMAR KR 19. JC273107F SUB MAJ & HONY LT MADAN SINGH 20. JC274128K SUB MAJ & HONY LT MOHANAN PILLAI C 21. JC275943K SUB MAJ & HONY LT NAGESWARA RAO P 22. JC273153W SUB MAJ & HONY LT RAMESH SINGH YADAV 23. JC272153K SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAMUNDRA SINGH 24. JC272199M SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAVARA LAKSHMANA RAO 25. JC272319A SUB MAJ & HONY LT SURESH KUMAR 26. JC273919P SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 27. JC271942K SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 28. JC279081N SUB & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH RATHORE 29. JC277689K SUB & HONY LT KAMBALA SREENIVASULU 30. JC277386P SUB & HONY LT PURUSHOTTAM PANDEY 31. JC279539M SUB & HONY LT RAMESH KUMAR SUBUDHI 32. -

Page 01 Sept 19.Indd

www.thepeninsulaqatar.com BUSINESS | 17 SPORT | 24 Opec may hold formal Rashidov and meeting if members Romarinho earn 2-1 agree on oil output win for El Jaish MONDAY 19 SEPTEMBER 2016 • 17 DHUL HIJJA 1437 • Volume 21 • Number 6924 2 Riyals thepeninsulaqatar @peninsulaqatar @peninsula_qatar New academic year Emir meets President of Panama starts on a high note Independent schools reported acquainted with the rules and reg- around 70 percent attendance on ulations. A teacher at the Al Maha The Minister of the first day, while it was higher in Academy, an international school Education and Higher most private schools. located in Ain Khaled said, children The ministry as part of its new were so excited on the first day and Education H E Dr disciplinary rules, has issued a some came even before the teachers Mohammed Abdul strong warning to students against arrived. The school offered refresh- Wahid Al Hammadi abstaining from classes in the fol- ments to parents who accompanied lowing days. their kids. visited a number of “Preparation for the new aca- Sana Salman, a mother of two Independent schools demic year was based on studies daughters studying at American conducted on past years’ experiences School Doha said, “Attendance was as Qatar started the and we focused on administrative, full on the first day. Different activi- new academic year organisational an academic aspects, ties took place at the school to cheer with the aim of improving quality up children and gear up for a new yesterday. and academic achievements. We start. The students were enthusias- have managed to fill all teachers’ tic attending the school after a long vacancies (in Independent schools) summer break.” with qualified hands and benefit- Nargis Raza, principal of Paki- By Amna Pervaiz Rao & ted from local talents,” said Fouzia Al stan Education Centre (PEC) said: Lojayn Motaz Eissa Khater, director of Education Insti- “There was heavy traffic at Abu The Peninsula tute at the Ministry. -

Article on Experience of My NCC Life Today I Am Going to Share My NCC Life Experience with You

Reg. No. AS18SDA133163 CSUO BISHAL DAS 4th ASSAM BATTALION NCC, KARIMGANJ KARIMGANJ COLLEGE, KARIMGANJ (ASSAM) Pin- 788710 Group SILCHAR NER DIRECTORATE Article on Experience of my NCC life Today I am going to share my NCC life experience with you. I had a dream to serve the country. That's why I want to join the Indian Army. When I passed HS, I first applied for recruitment in the Indian Army. 3rd January 2018 I was my first recruitment then I was physical and medical clear then I was very happy then gave us the date of written examination by recruitment agencie. I and one of my brothers, both, had passed, together, we both started preparing for the written examination. When we went to take the exam, my brother had a C-Certificate of NCC, that is why he did not have to give his written examination and I had to give the exam. When the results came, there was no Mara name in that list, but my brother's name was, My brother got a job in the Indian Army. Then I thought I would also join NCC. Then I reported in which college NCC is very good in our district. I got 4th Assam BN NCC at Karimganj in Karimganj College. Then I first joined the college, and to join the NCC, I approached the unit and told them to talk to the college's ANO. Then I saw the NCC enrollment notice in the college notic board and I contacted them and filed the form for joining NCC.He gave me the date of NCC selection 5th August 2018 I was very pleased. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

SUPPLEMENT to the LONDON GAZETTE, 22 MARCH, 1945 1547 No

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 22 MARCH, 1945 1547 No. SLAi420ig Corporal Samura Karonko, The The Indian Distinguished Service Medal. Sierra Leone Regiment, Royal West African No. F2553 Sweeper Ram Sarup, Indian Artillery. Frontier Force. No. 11988 Lance-Havildar Bhur Singh, ist Punjab No. GA245I Lance-Corporal SarrKba Jallow, The Regiment. Gambia Regiment, Royal West African Frontier No. 13625 Naik Qalandar Khan, ist Punjab Force. Regiment. No. GA25&5 Lance-Corporal Yaryah Jallow, The No. 12498 Lance-Havildar Purkha Ram, 2nd Punjab Gambia Regiment, Royal West African Frontier Regiment. Force. No. 13801 Naik iNur Khan, 2nd Punjab Regiment. No. GA.302I Private Kinti Kamara, The Gambia No. 9954 Naik Laxuman Shinde, 5th Mahratta Light Regiment, Royal West African Frontier Force. Infantry. No. GA2508 Private Dudu N'Dowe, The Gambia No. 12432 'Havildar Jagat Ram, loth Baluch Regiment, Royal West African Frontier Force. Regiment. No. GA3040 Private Musa N'Jie, The Gambia Regi- No. 22590 (Lance-Naik- Sita Ram, loth Baluch Regi- ment, Royal West African Frontier Force. ment. No. 12135 Company Sergeant-Major Waelo Chiwalo, No. 22207 Lance-Naik Makhmad Nabi, i3th Frontier The King's African Rifles. Force Rifles. No. 11672 Sergeant Akim Muhango, The King's No. 15394 Sepoy Ran Singh, i7th Dogra Regiment. Atfrican Rifles. No. 243 Havildar (acting) Alfred Kerketta, The No. Ni8o6 Sergeant Nekemiya, The King's African Rifles. Bihar Regiment. No. Ni8i5 Sergeant Yowana Owinja, The King's African Rifles. Burma Office, 22nd March, 1945. No. (N'209i Corporal Mohamed Aden, The King's African Rifles. The following awards have been made in recog- No. -

Supplement to the London Gazette, 22 March, 1945

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 22 MARCH, 1945 No. '3384853 Sergeant (acting) William Edward No. 25911 Lance-Naik Sana Ram, loth Baluch Regi- Maden, Tthe East Lancashire Regiment (Todmor- ment, Indian Army. den). No. 28383 Sepoy Hukam Chand, loth Baluch Regi- No. 3385357 Lance-Sergeant Kenneth Cross, The East ment, Indian Army. Lancashire Regiment (Morecambe). No. 23946 Sepoy Khitab, loth Baluch Regiment, No. 3386363 Corporal Alfred Clynch, The East Indian Army. Lancashire Regiment (Birkenhead). No. 21191 Lance-Naik Shangara Singh, i3th Frontier No. 5391.495 Corporal (acting) Joseph Govier, The Force Rifles, Indian Army. Royal Sussex Regiment (Brill, Bucks). No. 19552 Naik Mian Muhammed, i4th Punjab No. 6411142 Corporal (acting) Albert Harris, The Regiment, Indian Army. Royal Sussex Regiment ([London, W.2). No. 7152 Lance-Havildar Lakhu Ram, i7th Dogra No. 14497662 Private Christopher Alfred Colesby, Regiment, Indian Army. The Royal Sussex Regiment (London, N.I). No. 14743 Sepoy Falatu Ram, i7th Dogra Regi- No. 6148677 Private Victor Conetta, The Royal ment, Indian Army. Sussex Regiment (London, S.W.u). No. 11607 Sepoy Madho Ram, i7th Dogra Regiment, No. 14517101 Private John William Cox, The Royal Indian Army. Sussex Regiment (Erith). No. 8964 Havildar Man Singh, igth Hyderabad Regi- No. 6412096 Private Sidney John Powell, The Royal ment, Indian Army. Sussex Regiment (Kenton). No. 13449 Naik Partap Singh, igth Hyderabad Regi- No. 6412116 Private Frederick Charles George ment, Indian Army. Stonham, The Royal Sussex Regiment (Cobham). No. 21184 Sepoy Amar Singh, igth Hyderabad Regi- No. 14417029 Private Frederick James Clarke, The ment, Indian Army. Dorsetshire Regiment (Bristol). No. 2519 Sepoy Louis Toppo, The Bihar Regiment, No. -

Beyond Labor History's Comfort Zone? Labor Regimes in Northeast

Chapter 9 Beyond Labor History’s Comfort Zone? Labor Regimes in Northeast India, from the Nineteenth to the Twenty-First Century Willem van Schendel 1 Introduction What is global labor history about? The turn toward a world-historical under- standing of labor relations has upset the traditional toolbox of labor histori- ans. Conventional concepts turn out to be insufficient to grasp the dizzying array and transmutations of labor relations beyond the North Atlantic region and the industrial world. Attempts to force these historical complexities into a conceptual straitjacket based on methodological nationalism and Eurocentric schemas typically fail.1 A truly “global” labor history needs to feel its way toward new perspectives and concepts. In his Workers of the World (2008), Marcel van der Linden pro- vides us with an excellent account of the theoretical and methodological chal- lenges ahead. He makes it very clear that labor historians need to leave their comfort zone. The task at hand is not to retreat into a further tightening of the theoretical rigging: “we should resist the temptation of an ‘empirically empty Grand Theory’ (to borrow C. Wright Mills’s expression); instead, we need to de- rive more accurate typologies from careful empirical study of labor relations.”2 This requires us to place “all historical processes in a larger context, no matter how geographically ‘small’ these processes are.”3 This chapter seeks to contribute to a more globalized labor history by con- sidering such “small” labor processes in a mountainous region of Asia. My aim is to show how these processes challenge us to explore beyond the comfort zone of “labor history,” and perhaps even beyond that of “global labor history” * International Institute of Social History and University of Amsterdam. -

Geological and Tectonic Evolution of the Indo‑Myanmar Ranges (IMR) in the Myanmar Region

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Geological and tectonic evolution of the Indo‑Myanmar Ranges (IMR) in the Myanmar region Khin, Kyi; Zaw, Khin; Aung, Lin Thu 2017 Khin, K., Zaw, K., & Aung, L. T. (2017). Geological and tectonic evolution of the Indo‑Myanmar Ranges (IMR) in the Myanmar region. Geological Society Memoir, 48(1), 65‑79. doi:10.1144/M48.4 https://hdl.handle.net/10356/144426 https://doi.org/10.1144/M48.4 © 2017 The Author(s). All rights reserved. This paper was published by The Geological Society of London in Geological Society Memoir and is made available with permission of The Author(s). Downloaded on 10 Oct 2021 10:59:28 SGT Geological and tectonic evolution of the Indo-Myanmar Ranges (IMR) in the Myanmar region KYI KHIN1*, KHIN ZAW2 & LIN THU AUNG3 1SK Engineering and Construction, Singapore Branch, 415979, Singapore 2CODES ARC Centre of Excellence in Ore Deposits, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 126, Hobart, Tasmania 7001, Australia 3Earth Observatory of Singapore, Nanyang Technological University, 50 Nanyang Avenue, N2-01a-14, 639798, Singapore *Correspondence: [email protected] The Indo-Myanmar Ranges (IMR) of Myanmar, also known as of studies in the IMR of Myanmar aiming to understand the the Indo-Burman Ranges (IBR) or the Western Ranges, extend nature and origin of the continental crust beneath Myanmar, from the East Himalayan Syntaxis (EHS) southwards along the significant for Mesozoic and Cenozoic plate tectonic recon- eastern side of the Bay of Bengal to the Andaman Sea, compris- structions of Southeast Asia. -

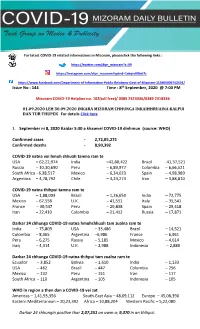

Task Group on Media and Publicity Daily Bulletin

ation please visit the following link : For latest COVID-19 related informations in Mizoram, pleaseclick the following links : https://twitter.com/dipr_mizoram?s=09 https://instagram.com/dipr_mizoram?igshid=1akqtv09bst7c https://www.facebook.com/Department-of-Information-Public-Relations-Govt-of-Mizoram-113605006752434/ Issue No : 144 Time : 8th September, 2020 @ 7:00 PM Mizoram COVID-19 Helpline no. 102(toll free)/ 0389 2323336/0389 2318336 01.09.2020 LEH 30.09.2020 INKARA MIZORAM CHHUNGA INKAIHHRUAINA KALPUI DAN TUR THUPEK For details Click here 1. September ni 8, 2020 tlaidar 5:30 a khawvel COVID-19 dinhmun (source: WHO) Confirmed cases - 2,72,05,275 Confirmed deaths - 8,90,392 COVID-19 natna vei hmuh chhuah tamna ram te USA – 62,22,974 India –42,80,422 Brazil -41,37,521 Russia – 10,30,690 Peru – 6,89,977 Colombia – 6,66,521 South Africa - 6,38,517 Mexico – 6,34,023 Spain – 4,98,989 Argentina – 4,78,792 Chile – 4,24,274 Iran – 3,88,810 COVID-19 natna thihpui tamna ram te USA – 1,88,003 Brazil – 1,26,650 India – 72,775 Mexico – 67,558 U.K. – 41,551 Italy – 35,541 France – 30,547 Peru – 29,838 Spain – 29,418 Iran – 22,410 Colombia – 21,412 Russia – 17,871 Darkar 24 chhunga COVID-19 natna hmuhchhuah tam zualna ram te India – 75,809 USA – 33,486 Brazil – 14,521 Colombia – 8,065 Argentina –6,986 France – 6,961 Peru – 6,275 Russia – 5,185 Mexico – 4,614 Iraq – 4,314 U.K. – 2,988 Indonesia – 2,880 Darkar 24 chhunga COVID-19 natna thihpui tam zualna ram te Ecuador – 3,852 Bolivia – 1,610 India – 1,133 USA – 462 Brazil – 447 Colombia – 256 Mexico – 232 Peru – 151 Iran – 117 South Africa – 110 Argentina – 105 Indonesia – 105 WHO in region a then dan a COVID-19 vei zat Americas – 1,41,93,356 South-East Asia – 48,69,112 Europe – 45,08,390 Eastern Mediterranean – 20,23,392 Africa – 10,88,204 Western Pacific – 5,22,080 Darkar 24 chhungin positive thar 2,07,251 an awm a; 9,370 in an thihpui. -

The Chin Hills-Arakan Yoma Montane Forests Are a Tropical and Subtropical Moist Broadleaf Forest Ecoregion in Western Myanmar

The Chin Hills-Arakan Yoma montane forests are a tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forest ecoregion in western Myanmar. Surrounded at lower elevations by moist tropical forests, this ecoregion is home a diverse range of subtropical and temperate species, including many species characteristic of the Himalayas, as well as many endemic species. The ecoregion covers an area of 29,700 square kilometers, encompassing the montane forests of the Arakan Mountain Range. The Chin Hills, which cover most of Chin State, and extend south along the ridge of the Arakan Mountains forms the boundary between Rakhine State on the west and Magway Region, Bago Region, and Ayeyarwady Region to the east. The ecoregion includes (Mount Victoria) in southern Chin State, which rises to 3071 meters above sea level. Home to many different ethnic groups who possess their own specific tattoo designs. The groups are historically related but speak divergent languages and dialects and have different cultural identities Chin tribe women wearing various pattern of tattoo on their face and attractive amber necklaces. The British first conquered Myanmar in 1824, established rule in 1886, and remained in power until Burma’s independence in 1948. The 1886 Chin Hills Regulation Act stated that the British would govern the Chins separately from the rest of Burma, which allowed for traditional Chin chiefs to remain in power. Burma’s independence from Britain in 1948 coincided with the Chin people adopting a democratic government rather than continuing its traditional rule of chiefs. Chin National Day is celebrated on February 20, the day that marks the transition from traditional to democratic rule in Chin State. -

“We Are Like Forgotten People”

“We Are Like Forgotten People” The Chin People of Burma: Unsafe in Burma, Unprotected in India Copyright © 2009 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 2-56432-426-5 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org January 2009 2-56432-426-5 “We Are Like Forgotten People” The Chin People of Burma: Unsafe in Burma, Unprotected in India Map of Chin State, Burma, and Mizoram State, India .......................................................... 1 Map of the Original Territory of Ethnic Chin Tribes .............................................................. 2 I. Summary ......................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................... 7 II. Background .................................................................................................................... 9 Brief Political History of the Chin ...................................................................................