Neofinetia Falcata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clonal Propagation of Phalaenopsis a Dissertation

CLONAL PROPAGATION OF PHALAENOPSIS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HORTICULTURE MAY 1974 By Oradee Intuwong DISSERTATION COMMITTEE: Yoneo Sagawa, Chairman Haruyuki Kamemoto Charles H. Lamoureux Henry Y. Nakasone John T. Kunisaki Marion 0. Mapes We certify that we have read this dissertation and that in our opinion it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Horticulture. DISSERTATION COMMITTEE CfaU6 Chairman 01j- <XAs<^<rv^ & ■ . ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The author expresses deep appreciation to the East-West Center, Harold L. Lyon Arboretum, Hawaii Agricultural Experiment Station, and Asia Foundation for their financial assistance to pursue graduate work at the University of Hawaii, and to Kodama Nursery for donation of some plant materials. ABSTRACT Phalaenopsis was clonally propagated by use of in vivo and _in vitro methods. In vivo, plantlets formed naturally on the node and tip of inflorescence, or root. Application of N-6-benzyl adenine to exposed buds on the inflorescence spike to induce plantlet formation was not very successful. Rapid clonal propagation was successfully accomplished by use of in vitro culture techniques. Explants from the nodal buds of inflorescence were the most suitable material for culture, although apical and axillary buds from the stem could also be used. When basal nodes from inflorescences after flowering or young inflorescences were cultured in basal media (BM = Vacin and Went 4- 15% coconut water), one to four plantlets rather than protocorm-like bodies (plbs) were obtained from a single node. -

Tools to Develop Genetic Model Plants in the Orchidaceae Family

ogy iol : Op r B e a n l A u c c c e l e Tsai and Sawa, Mol Biol 2018, 7:3 o s s M Molecular Biology: Open Access DOI: 10.4172/2168-9547.1000217 ISSN: 2168-9547 Short communication Open Access Tools to Develop Genetic Model Plants in the Orchidaceae Family Allen Yi-Lun Tsai and Shinichiro Sawa* Graduate School of Science & Technology, Kumamoto University, Kurokami 2-39-1, Kumamoto , Japan promote fungal growth contained within a plastic box [15]. Interestingly, Introduction G. pubilabiata was not only viable in the ACS, but was able to set seeds up to three times a year, compare to in the natural habitat where it may take at The Orchidaceae family is estimated to contain about 28,000 species least one year to set seed [15]. These results suggest that orchid generation and over 100,000 hybrids, making it one of the largest taxonomic time can potentially be shortened under artificial conditions, such that the groups among flowering plants [1]. The variations in flower colours, timeframes of genetic analyses become feasible. floral organ morphology and scents make orchids highly sought-after in ornamental horticulture. In addition, orchids are found in nearly In summary, advancements in the Orchidaceae family research all regions of the world with diverse adaptations, making them an highlight the orchids’ potential to be used as a genetic tool for basic invaluable resource to study plant evolution and speciation. research. One direction is to utilize orchid transposon as a mutation mapping tool. Phenotypic instability is a significant problem in the Despite orchids’ great economic values and potential in basic orchid breeding industry. -

PC22 Doc. 22.1 Annex (In English Only / Únicamente En Inglés / Seulement En Anglais)

Original language: English PC22 Doc. 22.1 Annex (in English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais) Quick scan of Orchidaceae species in European commerce as components of cosmetic, food and medicinal products Prepared by Josef A. Brinckmann Sebastopol, California, 95472 USA Commissioned by Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office FSVO CITES Management Authorithy of Switzerland and Lichtenstein 2014 PC22 Doc 22.1 – p. 1 Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms ........................................................................................................................ 7 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Information about the Databases Used ...................................................................................................... 11 1. Anoectochilus formosanus .................................................................................................................. 13 1.1. Countries of origin ................................................................................................................. 13 1.2. Commercially traded forms ................................................................................................... 13 1.2.1. Anoectochilus Formosanus Cell Culture Extract (CosIng) ............................................ 13 1.2.2. Anoectochilus Formosanus Extract (CosIng) ................................................................ 13 1.3. Selected finished -

The Role of Garden Plants in Modern Culture - Focusing Japanese Garden Plants

Reviews Korean J. Plant Res. 24(3) : 330~336 (2011) The Role of Garden Plants in Modern Culture - Focusing Japanese Garden Plants - Kaihei Koshio1, Tae-Soon Kim2, Jeong-Hwa Shin3, Won-Seob Song4 and Hee-Ock Boo5* 1Department of International Agricultural Development, Tokyo University of Agriculture, Tokyo 156-8502, Japan 2PHYTO M&F Co. Ltd., BI Center, Chosun University, Gwangju 501-759, Korea 3Korea Basic Science Institute, Seoul Center, Seoul 136-713, Korea 4Department of Horticulture, Sunchon National University, Jeonnam 540-742, Korea 5Department of Biology, Chosun Universitry, Gwangju 501-759, Korea Abstract - The recent disaster of earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011 severely attacked East Japanese cities and people, and in addition, the accident of nuclear power station will inevitably damage the agricultural activities there. The economical depression influences on the horticulture and floriculture industry as well, through the reluctant consumption all over the country. Such a situation reflects a conventional perception that the garden plants or ornamental plants have been regarded as a symbol of capitalism, representing the success, luxury, beauty or other metaphors indicating the winners of business war. But as the word “culture” means “cultivation” originally, horti“culture” or flori “culture” should have played some roles in cultivating lands as well as cultivation of human minds, leading to develop a modern “culture” which may lay emphases on personality, originality, partnership, cooperation, diversity and so forth. In this article, a brief history of garden plants in Japan, as well as some current movements in Japanese horticulture and floriculture, is reviewed with some commodities which possess messages on creating a new humane culture. -

Do Orchids Grow in Hawaii? and How!

Do Orchids Grow in Hawaii? And How! SYNOPSIS This is an historical sketch of the Saga of Orchids in Hawaii. The sequence of events from the incidental introduction of species by the Agriculturists for the Sugar Industry; to their efforts in propagation and culture, hybridizing and germination; to the development of personal nurseries to commercial ranges; and ultimately to the creation of a viable orchid industry, re cognized world wide; to the natural formation of orchid societies staging of orchid shows; and finally to the introduction of a system of orchid judging , should bring interesting reading to orchidists, amateur and professional alike. In fact, this could serve as a reference syllabus to keep. DO ORCHIDS GROW IM HAWAII? AMD HOW i Compiled and Edited by Dr. T. David Woo and Wallace K. Nakamoto Published under the auspices of The Hawaii Orchid Foundation for the American Orchid Society, Inc. Hawaii Regional Judging Center 1990 i TABLE OF CONTE NTS TABLE OF CONTENTS.................................................................................... i PREFACE........................................................................................................ vii PART I. INTRODUCTION OF ORCHIDS TO HAWAII.............................................. 1 The History of Orchids in Hawaii by Dr. T. David Woo ................................................................... 3 Development of Floriculture in Hawaii by J. H. Beaumont ................................................ 10 A Short History of Orchids in Hawaii by Loraine -

Intergeneric Make up Listing - September 1, 2017

Intergeneric Make Up Listing - September 1, 2017 Name: Abbr. Intergeneric Make-Up Aberconwayara Acw. Broughtonia x Caularthron x Guarianthe x Laelia Acampostylis Acy. Acampe x Rhynchostylis Acapetalum Acpt. Anacallis x Zygopetalum Aceratoglossum Actg. Aceras x Himantoglossum Acinbreea Acba. Acineta x Embreea Aciopea Aip. Acineta x Stanhopea Adachilium Adh. Ada x Cyrtochilum Adacidiglossum Adg. Brassia x Oncidiium x Rossioglossum Adacidium Adcm. Ada x Oncidium Adamara Adm. Brassavola x Cattleya x Epidendrum x Laelia Adapasia Adps. Ada x Aspasia Adenocalpa Adp. Adenoncos x Pomatoalpa Adioda Ado. Ada x Cochlioda Adonclinoda Anl. Ada x Cochiloda x Oncidium Adoncostele Ans. Ada x Oncidium x Rhynchostele Aerachnochilus Aac. Aerides x Arachnis x Staurochilis Aerangaeris Arg. Aerangis x Rangeris Aeranganthes Argt. Aerangis x Aeranthes Aeridachnanthe Aed. Aerides x Arachnis x Papilionanthe Aeridachnis Aerdns. Aerides x Arachnis Aeridochilus Aerchs. Aerides x Sarcochilus Aeridofinetia Aerf. Aerides x Neofinetia Aeridoglossum Aergm. Aerides x Ascoglossum Aeridoglottis Aegts. Aerides x Trichoglottis Aeridopsis Aerps. Aerides x Phalaenopsis Aeridovanda Aerdv. Aerides x Vanda Aeridovanisia Aervsa. Aerides x Luisia x Vanda Aeridsonia Ards. Aerides x Christensonia Aeristomanda Atom. Aerides x Cleisostoma x Vanda Aeroeonia Aoe. Aerangis x Oeonia Agananthes Agths. Aganisia x Cochleanthes Aganella All. Aganisia x Warczewiczella Aganopeste Agt. Aganisia x Lycaste x Zygopetalum Agasepalum Agsp. Aganisia x Zygosepalum Aitkenara Aitk. Otostylis x Zygopetalum x Zygosepalum Alantuckerara Atc. Neogardneria x Promenaea x Zygopetalum Aliceara Alcra. Brassia x Miltonia x Oncidium Allenara Alna. Cattleya x Diacrium x Epidendrum x Laelia Amenopsis Amn. Amesiella x Phalaenopsis Amesangis Am. Aerangis x Amesiella Amesilabium Aml. Amesiella x Tuberolabium Anabaranthe Abt. Anacheilium x Barkeria x Guarianthe Anabarlia Anb. -

11 November 2012.Pdf

TOWNSVILLE ORCHID SOCIETY INC NOVEMBER 2012 BULLETIN Full contact details are on our web site http://townsvilleorchidsociety.org.au TOS Inc. Directory of useful information: Postal Address: Hall Location: Meetings are held 8pm PO Box 836 D.C. Joe Kirwan Park on the 4th Friday of each AITKENVALE QLD 4814 Charles Street month except December Ph: 07 47734208 KIRWAN QLD in the Townsville Orchid Society Inc. Hall General Meeting Novice/New Growers’ Friday 23 November Christmas Luncheon Next Management at 8.00 pm Sunday 25 November Committee Meeting: at 12 noon Friday 11 January 2013 at 7.30 pm Patron: Phyllis Merritt President: Wal Nicholson Ph: 07 47734208 Secretary: Jean Nicholson Ph: 07 47734208 Email: [email protected] Assistant Treasurer: Charles Lee Ph: 07 4778 4815 VP Show: Marie Bloom Home: 07 47783497 VP Bulletin: Alis Siarni Mobile: 0406548057 TOS CALENDAR 2012 November 2012 23 – General Meeting at 8.00 pm 25 – Novice Growers’ Christmas Luncheon – 12 noon January 2013 11 - Management Committee Meeting – 7.30 pm Registrar’s Choice - Species Annual Membership Fees City Family $18.00 Pensioner Family $9.00 City Single $14.00 Pensioner Single/Junior $7.00 Details for paying membership fees: BSB: 064823 Account Number: 0009 0973 Name of Account: Townsville Orchid Society Inc. Commonwealth Bank, Aitkenvale Fees are due 1st September each year. Important Notification: The Bulletin will no longer be sent to un-financial members. A red dot on your Bulletin indicates that you are un-financial. Your name will be re-instated to the mailing list once your fees have been paid. -

(Neofinetia) Falcata: an Interview with Satomi Kasahara Phyllis Prestia

©Eric Hunt GROWING VANDA (NEOFINETIA) FALCATA: AN INTERVIEW WITH SATOMI KASAHARA PHYLLIS PRESTIA Neofinetia falcata HE SANTA BARBARA AREA is beautiful in Seed Engei the summer. Mild ocean breezes bathe the coast Shigeru Kasahara has been active in the Fūkiran So- under a warm California sun. For orchid lovers, T ciety in Japan for over 25 years and currently serves as it’s a paradise. July brings the annual open houses for the Chairman, an honored position. It was his friend’s two of the area orchid nurseries, Santa Barbara Orchid grandfather who gave him his first orchid, Dendrobium Estate and Cal-Orchid Inc. And for me, it brings an op- moniliforme and stirred his interest in native Japanese portunity to attend the meeting of the Fūkiran Society orchids. Shigeru loved plants, but Japanese orchids had of America and the annual Fūkiran judging, supported grabbed his heart. Eventually, Shigeru concentrated by the Japanese Fūkiran Society. For several years, the mostly on growing Fūkiran and sold them in his newly meeting and judging have been held on the property established flower shop. In 1983, he established Seed of Cal-Orchid Inc. on Saturday during the annual open Engei, a Japanese nursery which promotes and sells na- house weekend. This year they were held on July 14th, tive Japanese orchids and their hybrids. and this year I entered a few of my own Vanda falcata In the early 2000s, Shigeru visited the United States. orchids. He met Jason Fischer at his nursery, Orchids Limited The American Fūkiran Society was established in (Orchid Web.com) in Plymouth, Minnesota and the late 2012 as an offshoot of the Japan Fūkiran Society. -

Intergeneric Listing - August 2018

Intergeneric Listing - August 2018 Name: Abbrev. Intergeneric Make-Up Acampostylis Acy. Acampe x Rhynchostylis Acapetalum Acpt. Anacallis x Zygopetalum Acinbreea Acba. Acineta x Embreea Aciopea Aip. Acineta x Stanhopea Adacidium Adcm. Ada x Oncidium Adapasia Adps. Ada x Aspasia Adenocalpa Adp. Adenoncos x Pomatoalpa Adioda Ado. Ada x Cochlioda Adonclinoda Anl. Ada x Cochiloda x Oncidium Aerachnochilus Aac. Aerides x Arachnis x Staurochilis Aerangaeris Arg. Aerangis x Rangeris Aeranganthes Argt. Aerangis x Aeranthes Aeridachnanthe Aed. Aerides x Arachnis x Papilionanthe Aeridachnis Aerdns. Aerides x Arachnis Aeridochilus Aerchs. Aerides x Sarcochilus Aeridofinetia Aerf. Aerides x Neofinetia Aeridoglossum Aergm. Aerides x Ascoglossum Aeridoglottis Aegts. Aerides x Trichoglottis Aeridopsis Aerps. Aerides x Phalaenopsis Aeridovanda Aerdv. Aerides x Vanda Aeridovanisia Aervsa. Aerides x Luisia x Vanda Aeridsonia Ards. Aerides x Christensonia Aeristomanda Atom. Aerides x Cleisostoma x Vanda Aeroeonia Aoe. Aerangis x Oeonia Agananthes Agths. Aganisia x Cochleanthes Aganella All. Aganisia x Warczewiczella Aganopeste Agt. Aganisia x Lycaste x Zygopetalum Agasepalum Agsp. Aganisia x Zygosepalum Aitkenara Aitk. Otostylis x Zygopetalum x Zygosepalum Alantuckerara Atc. Neogardneria x Promenaea x Zygopetalum Aliceara Alcra. Brassia x Miltonia x Oncidium Allenara Alna. Cattleya x Diacrium x Epidendrum x Laelia Amenopsis Amn. Amesiella x Phalaenopsis Amesangis Am. Aerangis x Amesiella Amesilabium Aml. Amesiella x Tuberolabium Anabaranthe Abt. Anacheilium x Barkeria x Guarianthe Anabarlia Anb. Anacamptis x Barlia Anacamptiplatanthera An. Anacamptis x Platanthera Anacamptorchis Ana. Anacamptis x Orchis Anagymnorhiza Agz. Anacamptis x Dactylorhiza x Gymnadenia Anamantoglossum Amtg. Anacamptis x Himantoglossum Anaphorkis Apk. Ansellia x Graphorkis Ancistrolanthe Anh. Ancistrochilus x Calanthe Ancistrophaius Astp. Ancistrochilus x Phaius Andersonara Ande. Brassavola x Cattleya x Caularthron x Guarianthe x Laelia x Rhyncholaelia Andreara Andr. -

Cold Tolerance of Orchids

St. Augustine Orchid Society www.staugorchidsociety.org Cold Tolerance of Warm Growing Orchids by Sue Bottom, [email protected] If you allow your orchids the pleasure of growing outside during the warm season, they will reward you with an abundance of growth and blooms. You may have to make some adjustments to protect your orchids when the cool season arrives. Some orchids are very intolerant of cold and may have to be relocated to a warm winter home while others are more cold tolerant and may only need protection on the coldest nights. Each type of orchid has its preferred minimum night temperatures during the winter cool season, below which cold damage to the plant will occur. Most phalaenopsis, the large two toned vandas, the evergreen dendrobiums and the mule eared oncidiums are the least tolerant of cold, preferring night time temperatures above 60oF though some tolerate temperatures in the 50’s. Most cattleyas and oncidiums prefer winter night temperatures in the mid 50’s though some tolerate temperatures in the mid 40’s. Deciduous dendrobiums bloom better after a cooler, drier winter rest period with no fertilizer tolerating temperatures in the low to mid 40’s. Dendrocoryne dendrobiums and cymbidiums are the most cold tolerant orchids of those that can grow in summer heat accepting of temperatures down into the 30’s. Cattleyas. As a general rule, cattleya alliance plants prefer temperatures above 55oF though many will tolerate temperatures into the mid 40’s. Cattleyas from the Amazon like C. violacea prefer warmer temperatures, and there are many cold hardy varieties that tolerate temperatures in the mid to upper 30’s, like C. -

NEWSLETTER October 2017

NEWSLETTER October 2017 Volume 12 Issue #10 CLUB NEWS October 3 SAOS Remember to email our Club librarian, Penny Halyburton Meeting ([email protected]) with your book/DVD by Janis Croft your request and she will bring the item(s) to the next [email protected] meeting. The library collection is listed on our SAOS website. Welcome and Thanks. Bob Schimmel opened the meeting at 7:00 pm sharp with 54 attendees. Susan Smith introduced our three guests. Bob then thanked Dorianna Borrero, Daisy Thompson and Jeanette Kristen Uthus Smith for organizing the refreshments and reminded all to drop a dollar in the basket while enjoying their refreshments. Bob stated that the Best of Show voting would occur between the Show Table discussion and the auction and encouraged all to vote for their favorite orchid. Bob announced the nominating committee (Susan Smith, Linda Stewart and Sue Bottom) who will recommend the Show Table Review. Courtney Hackney commented upon 2018 slate of SAOS officers next month. All are encouraged how many miniature plants were on display this month to come and vote. and started with the indigo colored Phal (Doritaenopsis) Purple Martin that was described as cute. Most miniature Club Business. The next and final-for-the-year Ace phals like to be mounted or potted with a sphagnum moss Repotting Clinic will be Oct. 7 from 9 am til 1 pm. base and watered when moss is dry. Grower Linda Stewart October shows in Florida include South Florida Orchid said that she waters with rain water with better success Show, Gainesville Orchid Show, Delray Beach Orchid at blooming the plant. -

Orchid Name Abbreviations List

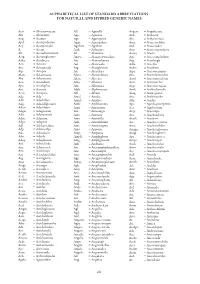

ALPHABETICAL LIST OF STANDARD ABBREVIATIONS FOR NATURAL AND HYBRID GENERIC NAMES Acw. = Aberconwayara All. = Aganella Angcst. = Angulocaste Abr. = Aberrantia Agn. = Aganisia Ank. = Anikaara Acp. = Acampe Agt. = Aganopeste Akr. = Ankersmitara Apd. = Acampodorum Agsp. = Agasepalum Anct. = Anoectochilus Acy. = Acampostylis Agubata = Agubata Atd. = Anoectodes A. = Aceras Aitk. = Aitkenara Ano. = Anoectogoodyera Ah. = Acerasherminium Al. = Alamania Anota = Anota Actg. = Aceratoglossum Agwa. = Alangreatwoodara Ayp. = Ansecymphyllum Acba. = Acinbreea Atc. = Alantuckerara Asg. = Anselangis Acn. = Acineta Aat. = Alaticaulia Aslla. = Ansellia Ain. = Acinopetala Atg. = Alatiglossum Asdm. = Ansidium Aip. = Aciopea Alc. = Alcockara Arpt. = Anteriocamptis Akm. = Ackermania Alxra. = Alexanderara Ahc. = Anterioherorchis Aks. = Ackersteinia Alcra. = Aliceara Atml. = Anteriomeulenia Aco. = Acoridium Alna. = Allenara Antr. = Anteriorchis Apa. = Acrolophia Aln. = Allioniara Atsp. = Anterioserapias Aro. = Acronia Alph. = Alphonsoara Anth. = Anthechostylis Acro. = Acropera Alv. = Alvisia Antg. = Antheglottis Ada = Ada Amal. = Amalia Anr. = Antheranthe Adh. = Adachilum Amals. = Amalias Alla. = Antilla Adg. = Adacidiglossum Amb. = Amblostoma Apr. = Apoda-prorepentia Adcm. = Adacidium Amn. = Amenopsis Aea. = Appletonara Adgm. = Adaglossum Am. = Amesangis Arcp. = Aracampe Adn. = Adamantinia Ams. = Amesara Ara. = Arachnadenia Adm. = Adamara Ame. = Amesiella Arach. = Arachnis Adps. = Adapasia Aml. = Amesilabium Act. = Arachnocentron Adl. = Adelopetalum Ami. = Amitostigma