Algorithms, Turing Machines and Algorithmic Undecidability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMPSCI 501: Formal Language Theory Insights on Computability Turing Machines Are a Model of Computation Two (No Longer) Surpris

Insights on Computability Turing machines are a model of computation COMPSCI 501: Formal Language Theory Lecture 11: Turing Machines Two (no longer) surprising facts: Marius Minea Although simple, can describe everything [email protected] a (real) computer can do. University of Massachusetts Amherst Although computers are powerful, not everything is computable! Plus: “play” / program with Turing machines! 13 February 2019 Why should we formally define computation? Must indeed an algorithm exist? Back to 1900: David Hilbert’s 23 open problems Increasingly a realization that sometimes this may not be the case. Tenth problem: “Occasionally it happens that we seek the solution under insufficient Given a Diophantine equation with any number of un- hypotheses or in an incorrect sense, and for this reason do not succeed. known quantities and with rational integral numerical The problem then arises: to show the impossibility of the solution under coefficients: To devise a process according to which the given hypotheses or in the sense contemplated.” it can be determined in a finite number of operations Hilbert, 1900 whether the equation is solvable in rational integers. This asks, in effect, for an algorithm. Hilbert’s Entscheidungsproblem (1928): Is there an algorithm that And “to devise” suggests there should be one. decides whether a statement in first-order logic is valid? Church and Turing A Turing machine, informally Church and Turing both showed in 1936 that a solution to the Entscheidungsproblem is impossible for the theory of arithmetic. control To make and prove such a statement, one needs to define computability. In a recent paper Alonzo Church has introduced an idea of “effective calculability”, read/write head which is equivalent to my “computability”, but is very differently defined. -

Edsger Dijkstra: the Man Who Carried Computer Science on His Shoulders

INFERENCE / Vol. 5, No. 3 Edsger Dijkstra The Man Who Carried Computer Science on His Shoulders Krzysztof Apt s it turned out, the train I had taken from dsger dijkstra was born in Rotterdam in 1930. Nijmegen to Eindhoven arrived late. To make He described his father, at one time the president matters worse, I was then unable to find the right of the Dutch Chemical Society, as “an excellent Aoffice in the university building. When I eventually arrived Echemist,” and his mother as “a brilliant mathematician for my appointment, I was more than half an hour behind who had no job.”1 In 1948, Dijkstra achieved remarkable schedule. The professor completely ignored my profuse results when he completed secondary school at the famous apologies and proceeded to take a full hour for the meet- Erasmiaans Gymnasium in Rotterdam. His school diploma ing. It was the first time I met Edsger Wybe Dijkstra. shows that he earned the highest possible grade in no less At the time of our meeting in 1975, Dijkstra was 45 than six out of thirteen subjects. He then enrolled at the years old. The most prestigious award in computer sci- University of Leiden to study physics. ence, the ACM Turing Award, had been conferred on In September 1951, Dijkstra’s father suggested he attend him three years earlier. Almost twenty years his junior, I a three-week course on programming in Cambridge. It knew very little about the field—I had only learned what turned out to be an idea with far-reaching consequences. a flowchart was a couple of weeks earlier. -

The Turing Approach Vs. Lovelace Approach

Connecting the Humanities and the Sciences: Part 2. Two Schools of Thought: The Turing Approach vs. The Lovelace Approach* Walter Isaacson, The Jefferson Lecture, National Endowment for the Humanities, May 12, 2014 That brings us to another historical figure, not nearly as famous, but perhaps she should be: Ada Byron, the Countess of Lovelace, often credited with being, in the 1840s, the first computer programmer. The only legitimate child of the poet Lord Byron, Ada inherited her father’s romantic spirit, a trait that her mother tried to temper by having her tutored in math, as if it were an antidote to poetic imagination. When Ada, at age five, showed a preference for geography, Lady Byron ordered that the subject be replaced by additional arithmetic lessons, and her governess soon proudly reported, “she adds up sums of five or six rows of figures with accuracy.” Despite these efforts, Ada developed some of her father’s propensities. She had an affair as a young teenager with one of her tutors, and when they were caught and the tutor banished, Ada tried to run away from home to be with him. She was a romantic as well as a rationalist. The resulting combination produced in Ada a love for what she took to calling “poetical science,” which linked her rebellious imagination to an enchantment with numbers. For many people, including her father, the rarefied sensibilities of the Romantic Era clashed with the technological excitement of the Industrial Revolution. Lord Byron was a Luddite. Seriously. In his maiden and only speech to the House of Lords, he defended the followers of Nedd Ludd who were rampaging against mechanical weaving machines that were putting artisans out of work. -

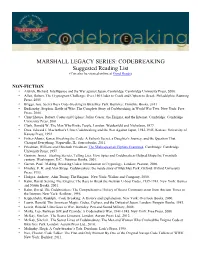

CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can Also Be Viewed Online at Good Reads)

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can also be viewed online at Good Reads) NON-FICTION • Aldrich, Richard. Intelligence and the War against Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. • Allen, Robert. The Cryptogram Challenge: Over 150 Codes to Crack and Ciphers to Break. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2005 • Briggs, Asa. Secret Days Code-breaking in Bletchley Park. Barnsley: Frontline Books, 2011 • Budiansky, Stephen. Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War Two. New York: Free Press, 2000. • Churchhouse, Robert. Codes and Ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. • Clark, Ronald W. The Man Who Broke Purple. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1977. • Drea, Edward J. MacArthur's Ultra: Codebreaking and the War Against Japan, 1942-1945. Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 1992. • Fisher-Alaniz, Karen. Breaking the Code: A Father's Secret, a Daughter's Journey, and the Question That Changed Everything. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2011. • Friedman, William and Elizebeth Friedman. The Shakespearian Ciphers Examined. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957. • Gannon, James. Stealing Secrets, Telling Lies: How Spies and Codebreakers Helped Shape the Twentieth century. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2001. • Garrett, Paul. Making, Breaking Codes: Introduction to Cryptology. London: Pearson, 2000. • Hinsley, F. H. and Alan Stripp. Codebreakers: the inside story of Bletchley Park. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. • Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing: The Enigma. New York: Walker and Company, 2000. • Kahn, David. Seizing The Enigma: The Race to Break the German U-boat Codes, 1939-1943. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 2001. • Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet. -

An Early Program Proof by Alan Turing F

An Early Program Proof by Alan Turing F. L. MORRIS AND C. B. JONES The paper reproduces, with typographical corrections and comments, a 7 949 paper by Alan Turing that foreshadows much subsequent work in program proving. Categories and Subject Descriptors: 0.2.4 [Software Engineeringj- correctness proofs; F.3.1 [Logics and Meanings of Programs]-assertions; K.2 [History of Computing]-software General Terms: Verification Additional Key Words and Phrases: A. M. Turing Introduction The standard references for work on program proofs b) have been omitted in the commentary, and ten attribute the early statement of direction to John other identifiers are written incorrectly. It would ap- McCarthy (e.g., McCarthy 1963); the first workable pear to be worth correcting these errors and com- methods to Peter Naur (1966) and Robert Floyd menting on the proof from the viewpoint of subse- (1967); and the provision of more formal systems to quent work on program proofs. C. A. R. Hoare (1969) and Edsger Dijkstra (1976). The Turing delivered this paper in June 1949, at the early papers of some of the computing pioneers, how- inaugural conference of the EDSAC, the computer at ever, show an awareness of the need for proofs of Cambridge University built under the direction of program correctness and even present workable meth- Maurice V. Wilkes. Turing had been writing programs ods (e.g., Goldstine and von Neumann 1947; Turing for an electronic computer since the end of 1945-at 1949). first for the proposed ACE, the computer project at the The 1949 paper by Alan M. -

Turing's Influence on Programming — Book Extract from “The Dawn of Software Engineering: from Turing to Dijkstra”

Turing's Influence on Programming | Book extract from \The Dawn of Software Engineering: from Turing to Dijkstra" Edgar G. Daylight∗ Eindhoven University of Technology, The Netherlands [email protected] Abstract Turing's involvement with computer building was popularized in the 1970s and later. Most notable are the books by Brian Randell (1973), Andrew Hodges (1983), and Martin Davis (2000). A central question is whether John von Neumann was influenced by Turing's 1936 paper when he helped build the EDVAC machine, even though he never cited Turing's work. This question remains unsettled up till this day. As remarked by Charles Petzold, one standard history barely mentions Turing, while the other, written by a logician, makes Turing a key player. Contrast these observations then with the fact that Turing's 1936 paper was cited and heavily discussed in 1959 among computer programmers. In 1966, the first Turing award was given to a programmer, not a computer builder, as were several subsequent Turing awards. An historical investigation of Turing's influence on computing, presented here, shows that Turing's 1936 notion of universality became increasingly relevant among programmers during the 1950s. The central thesis of this paper states that Turing's in- fluence was felt more in programming after his death than in computer building during the 1940s. 1 Introduction Many people today are led to believe that Turing is the father of the computer, the father of our digital society, as also the following praise for Martin Davis's bestseller The Universal Computer: The Road from Leibniz to Turing1 suggests: At last, a book about the origin of the computer that goes to the heart of the story: the human struggle for logic and truth. -

Alan Turing, Marshall Hall, and the Alignment of WW2 Japanese Naval Intercepts

Alan Turing, Marshall Hall, and the Alignment of WW2 Japanese Naval Intercepts Peter W. Donovan arshall Hall Jr. (1910–1990) is de- The statistician Edward Simpson led the JN-25 servedly well remembered for his team (“party”) at Bletchley Park from 1943 to 1945. role in constructing the simple group His now declassified general history [12] of this of order 604800 = 27 × 33 × 52 × 7 activity noted that, in November 1943: Mas well as numerous advances in [CDR Howard Engstrom, U.S.N.] gave us combinatorics. A brief autobiography is on pages the first news we had heard of a method 367–374 of Duran, Askey, and Merzbach [5]. Hall of testing the correctness of the relative notes that Howard Engstrom (1902–1962) gave setting of two messages using only the him much help with his Ph.D. thesis at Yale in property of divisibility by three of the code 1934–1936 and later urged him to work in Naval In- groups [5-groups is the usage of this paper]. telligence (actually in the foreign communications The method was known as Hall’s weights unit Op-20-G). and was a useful insurance policy just in I was in a research division and got to see case JN-25 ever became more difficult. He work in all areas, from the Japanese codes promised to send us a write-up of it. to the German Enigma machine which Alan The JN-25 series of ciphers, used by the Japanese Turing had begun to attack in England. I Navy (I.J.N.) from 1939 to 1945, was the most made significant results on both of these important source of communications intelligence areas. -

Alan Turing's Forgotten Ideas

Alan Turing, at age 35, about the time he wrote “Intelligent Machinery” Copyright 1998 Scientific American, Inc. lan Mathison Turing conceived of the modern computer in 1935. Today all digital comput- Aers are, in essence, “Turing machines.” The British mathematician also pioneered the field of artificial intelligence, or AI, proposing the famous and widely debated Turing test as a way of determin- ing whether a suitably programmed computer can think. During World War II, Turing was instrumental in breaking the German Enigma code in part of a top-secret British operation that historians say short- ened the war in Europe by two years. When he died Alan Turing's at the age of 41, Turing was doing the earliest work on what would now be called artificial life, simulat- ing the chemistry of biological growth. Throughout his remarkable career, Turing had no great interest in publicizing his ideas. Consequently, Forgotten important aspects of his work have been neglected or forgotten over the years. In particular, few people— even those knowledgeable about computer science— are familiar with Turing’s fascinating anticipation of connectionism, or neuronlike computing. Also ne- Ideas glected are his groundbreaking theoretical concepts in the exciting area of “hypercomputation.” Accord- ing to some experts, hypercomputers might one day in solve problems heretofore deemed intractable. Computer Science The Turing Connection igital computers are superb number crunchers. DAsk them to predict a rocket’s trajectory or calcu- late the financial figures for a large multinational cor- poration, and they can churn out the answers in sec- Well known for the machine, onds. -

Axiomatic Set Teory P.D.Welch

Axiomatic Set Teory P.D.Welch. August 16, 2020 Contents Page 1 Axioms and Formal Systems 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Preliminaries: axioms and formal systems. 3 1.2.1 The formal language of ZF set theory; terms 4 1.2.2 The Zermelo-Fraenkel Axioms 7 1.3 Transfinite Recursion 9 1.4 Relativisation of terms and formulae 11 2 Initial segments of the Universe 17 2.1 Singular ordinals: cofinality 17 2.1.1 Cofinality 17 2.1.2 Normal Functions and closed and unbounded classes 19 2.1.3 Stationary Sets 22 2.2 Some further cardinal arithmetic 24 2.3 Transitive Models 25 2.4 The H sets 27 2.4.1 H - the hereditarily finite sets 28 2.4.2 H - the hereditarily countable sets 29 2.5 The Montague-Levy Reflection theorem 30 2.5.1 Absoluteness 30 2.5.2 Reflection Theorems 32 2.6 Inaccessible Cardinals 34 2.6.1 Inaccessible cardinals 35 2.6.2 A menagerie of other large cardinals 36 3 Formalising semantics within ZF 39 3.1 Definite terms and formulae 39 3.1.1 The non-finite axiomatisability of ZF 44 3.2 Formalising syntax 45 3.3 Formalising the satisfaction relation 46 3.4 Formalising definability: the function Def. 47 3.5 More on correctness and consistency 48 ii iii 3.5.1 Incompleteness and Consistency Arguments 50 4 The Constructible Hierarchy 53 4.1 The L -hierarchy 53 4.2 The Axiom of Choice in L 56 4.3 The Axiom of Constructibility 57 4.4 The Generalised Continuum Hypothesis in L. -

Charles Babbage (1791-1871)

History of Computer abacus invented in ancient China Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) ! Blaise Pascal was a French mathematician Pascal’s calculators ran with gears and wheels Pascal Calculator Charles Babbage (1791-1871) Charles Babbage was an English mathematician. Considered a “father of the computer” He invented computers but failed to build them. The first complete Babbage Engine was completed in London in 2002, 153 years after it was designed. Babbage Engine Alan Turing (1912-1954) Alan Turing was a British computer scientist. ! He proposed the concepts of "algorithm" and "computation" with the Turing machine in 1936 , which can be considered a model of a general purpose computer. Alan Turing (1912-1954) During the second World War, Turing worked for Britain’s code breaking centre. He devised a number of techniques for breaking German ciphers. Turing was prosecuted in 1952 for homosexual acts. He accepted treatment with estrogen injections (chemical castration) as an alternative to prison. Grace Hopper (1906–1992) Grace Hopper was an American computer scientist and United ! States Navy rear admiral. She created a compiler system that translated mathematical code into machine language. Later, the compiler became the forerunner to modern programming languages Grace Hopper (1906–1992) In 1947, Hopper and her assistants were working on the "granddaddy" of modern computers, the Harvard Mark II. "Things were going badly; there was something wrong in one of the circuits of the long glass- enclosed computer," she said. Finally, someone located the trouble spot and, using ordinary The bug is so famous, tweezers, removed the problem, a you can actually see two- inch moth. -

Undecidable Problems: a Sampler (.Pdf)

UNDECIDABLE PROBLEMS: A SAMPLER BJORN POONEN Abstract. After discussing two senses in which the notion of undecidability is used, we present a survey of undecidable decision problems arising in various branches of mathemat- ics. 1. Introduction The goal of this survey article is to demonstrate that undecidable decision problems arise naturally in many branches of mathematics. The criterion for selection of a problem in this survey is simply that the author finds it entertaining! We do not pretend that our list of undecidable problems is complete in any sense. And some of the problems we consider turn out to be decidable or to have unknown decidability status. For another survey of undecidable problems, see [Dav77]. 2. Two notions of undecidability There are two common settings in which one speaks of undecidability: 1. Independence from axioms: A single statement is called undecidable if neither it nor its negation can be deduced using the rules of logic from the set of axioms being used. (Example: The continuum hypothesis, that there is no cardinal number @0 strictly between @0 and 2 , is undecidable in the ZFC axiom system, assuming that ZFC itself is consistent [G¨od40,Coh63, Coh64].) The first examples of statements independent of a \natural" axiom system were constructed by K. G¨odel[G¨od31]. 2. Decision problem: A family of problems with YES/NO answers is called unde- cidable if there is no algorithm that terminates with the correct answer for every problem in the family. (Example: Hilbert's tenth problem, to decide whether a mul- tivariable polynomial equation with integer coefficients has a solution in integers, is undecidable [Mat70].) Remark 2.1. -

Axioms of Set Theory and Equivalents of Axiom of Choice Farighon Abdul Rahim Boise State University, [email protected]

Boise State University ScholarWorks Mathematics Undergraduate Theses Department of Mathematics 5-2014 Axioms of Set Theory and Equivalents of Axiom of Choice Farighon Abdul Rahim Boise State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.boisestate.edu/ math_undergraduate_theses Part of the Set Theory Commons Recommended Citation Rahim, Farighon Abdul, "Axioms of Set Theory and Equivalents of Axiom of Choice" (2014). Mathematics Undergraduate Theses. Paper 1. Axioms of Set Theory and Equivalents of Axiom of Choice Farighon Abdul Rahim Advisor: Samuel Coskey Boise State University May 2014 1 Introduction Sets are all around us. A bag of potato chips, for instance, is a set containing certain number of individual chip’s that are its elements. University is another example of a set with students as its elements. By elements, we mean members. But sets should not be confused as to what they really are. A daughter of a blacksmith is an element of a set that contains her mother, father, and her siblings. Then this set is an element of a set that contains all the other families that live in the nearby town. So a set itself can be an element of a bigger set. In mathematics, axiom is defined to be a rule or a statement that is accepted to be true regardless of having to prove it. In a sense, axioms are self evident. In set theory, we deal with sets. Each time we state an axiom, we will do so by considering sets. Example of the set containing the blacksmith family might make it seem as if sets are finite.