HOW to BUY a EUPHONIUM by Mark Kellogg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schagerl Instruments

SCHAGERL® PFLEGEHINWEISE, GARANTIEBESTIMMUNGEN & AGB (INSTRUCTIONS FOR CARE, GUARANTEE, TERMS AND CONDITIONS) Auf unserem Schagerl Video Channel www.youtube.com/SchagerlClub REGISTER NOW AND EXTEND YOUR WARRANTY PERIOD OF YOUR INSTRUMENT FROM 24 TO 36 MONTH! finden Sie unter der Playlist www.schagerl.com/instrumentenregistrierung Instrumentenpflege (Care Instructions for Instruments) Pflegeanleitungen als Video in Full HD! For all instruments acquired on or after 1 January 2016, the warranty period is extended to 36 months if and provided that the buyer registers these instruments within 8 weeks after the date of purchase. Registration can only be done online at www.schagerl.com/instrumentenregistrierung. Care Notes for Rotary Valve Instruments due to the extremely precise construction the rotary valve system, these procedures should be followed with care. EN 5 6 Care Products: 1 for the valves4Hetman Light Rotor 11* (or Schagerl Valve Oil) for the linkages4Hetman Ball Joint 15* (or Ultra Pure Linkage Oil) for the triggers4Hetman Slide Oil 5* for the slides4Hetman Slide Grease 8* (or Ultra Pure Regular) for the ball joint4Hetman Slide Grease 8* (or Ultra Pure Regular) We recommend a yearly instrument service at Schagerl Music Gmbh or one of our representatives. for the lacquer, silver and gold4Glass cleaner and a soft cloth i 2 Application: after every use: 1 drop Hetman Light Rotor in each upper valve post, 1 drop in lower valve post (unscrew bottom valve cap) , Slide Grease 6 8* on each slide. every 2 - 3 weeks: 1 drop Hetman Ball Joint on the mini-ball linkages , oil the cross braces 3rd slide with Hetman Slide Oil 5* , Lubri- 3 4 cate the other slides and linkages with Hetman Slide Grease 8* once a month: remove the main tuning slide and run water backwards through the valves towards the leadpipe while not moving the valves. -

Fluid Power, Rate Training Manual

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 070 578 SE 014 125 TITLE Fluid Power, Rate TrainingManual. INSTITUTION Bureau of Naval Personnel,Washington, D. C. REPORT NO NAVPERS-16193-B PUB DATE 70 NOTE 305p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$13.16 DESCRIPTORS Force; *Hydraulics; Instructional Materials; *Mechanical Equipment; Military Personnel; *Military Science; *Military Training; Physics; *Supplementary Textbooks; Textbooks ABSTRACT Fundamentals of hydraulics and pneumatics are presented in this manual, prepared for regular navy and naval reserve personnel who are seeking advancement to Petty Officer Third Class. The history of applications of compressed fluids is described in connection with physical principles. Selection of types of liquids and gases is discussed with a background of operating temperature ranges, contamination control techniques, lubrication aspects, and safety precautions. Components in closed- and open-center fluid systems are studied in efforts to familiarize circuit diagrams. Detailed descriptions are made for .the functions of fluidlines, connectors, sealing devices, wipers, backup washers, containers, strainers, filters, accumulators, pumps, and compressors. Control and measurements of fluid flow and pressure are analyzed in terms of different types of flowmeters, pressure gages, and values; and methods of directing flow and converting power into mechanical force and motion, in terms of directional control valves, actuating cylinders, fluid motors, air turbines, and turbine governors. Also included are studies of fluidics, trouble shooting, hydraulic power drive, electrohydraulic steering, and missile and aircraft fluid power systems. Illustrations for explanation use and a glossary of general terms are included in the appendix. (CC) IDLE AV Agile 4'Aly , _ - , 141 ye ,,- I -,, FLUID POWER BUREAU OF OF NAVAL PERSONNEL .1% RATE TRAINING MANUAL NAVPERS 16,1937B PREFACE Fluid Power is written for personnel of the Navy and Naval Reserve whose duties and responsibilities require them to have a knowledge of the fundamentals of hydraulics and pneumatics. -

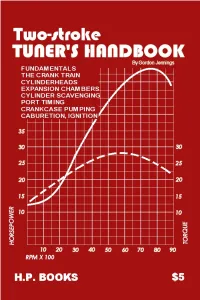

Jennings: Two-Stroke Tuner's Handbook

Two-Stroke TUNER’S HANDBOOK By Gordon Jennings Illustrations by the author Copyright © 1973 by Gordon Jennings Compiled for reprint © 2007 by Ken i PREFACE Many years have passed since Gordon Jennings first published this manual. Its 2007 and although there have been huge technological changes the basics are still the basics. There is a huge interest in vintage snowmobiles and their “simple” two stroke power plants of yesteryear. There is a wealth of knowledge contained in this manual. Let’s journey back to 1973 and read the book that was the two stroke bible of that era. Decades have passed since I hung around with John and Jim. John and I worked for the same corporation and I found a 500 triple Kawasaki for him at a reasonable price. He converted it into a drag bike, modified the engine completely and added mikuni carbs and tuned pipes. John borrowed Jim’s copy of the ‘Two Stoke Tuner’s Handbook” and used it and tips from “Fast by Gast” to create one fast bike. John kept his 500 until he retired and moved to the coast in 2005. The whereabouts of Wild Jim, his 750 Kawasaki drag bike and the only copy of ‘Two Stoke Tuner’s Handbook” that I have ever seen is a complete mystery. I recently acquired a 1980 Polaris TXL and am digging into the inner workings of the engine. I wanted a copy of this manual but wasn’t willing to wait for a copy to show up on EBay. Happily, a search of the internet finally hit on a Word version of the manual. -

Fluent in French

Fluent in French A Band Director’s Guide to Understanding and Teaching the French Horn Practical Application Project #1 MUSI 6285 Jonathan Bletscher 2 Table of Contents Introduction 4 Part One: Understanding the Horn 5 Horn History 5 Rotary Valves and Anatomy of the Horn 8 - Common Rotary Valve Problems 12 - Disassembling and Reassembling a Rotary Valve 14 - Replacing Rotary Valve String 21 Horn in F and Horn in Bb: Transposing Instruments 26 The Seven Chromatic Brass Fingerings 28 The Overtone Series 30 7 Fingerings, 7 Fundamentals, and 7 Series: Filling in the Gaps 35 The Partial Grouping Method 37 Horn Fingering Tricks 41 Trouble Fitting In: Why Horns Aren’t Like Everyone Else (In the Brass Family) 45 Part Two: Teaching the Horn 47 Picking Your Horn Players 47 Equipping for Success 48 Posture and Holding the Horn 49 Making a Sound on the Horn 53 Common Problems with Horn Embouchure 56 Horn Fingerings 58 Instrument Maintenance 61 Developing as a Horn Player 63 Teaching Strategies 67 More to Learn 70 About the Author 71 Bibliography 72 3 Introduction Consider a student who is about to begin the very frst day of learning a foreign language. The student is pre- sented with very basic vocabulary, is led to dabble in speaking and writing, and very slowly begins absorbing the sound, feel, and structure of the language. This is not unlike the experience of a student learning his or her frst instrument. This slow and steady approach is designed to be the frst step in a years-long sequence of instruction and study for a student who is brand new to the subject. -

Bishop Rotary Valve Engine

Advanced Engine Technology The Bishop Rotary Valve by Tony Wallis, Bishop Innovation To demonstrate the credibility of Bishop Innovation’s new rotary valve technology it joined forces with Mercedes-Ilmor to develop the technology for use on their V10 Formula One engine only to have its strategy destroyed by a change in engine regulations. 10% power By the early 1990s Bishop Inno- offered by the rotary valve. Fur- ney Australia. Bishop was respon- advantage vation had completed the initial ther, a successful public demon- sible for the cylinder head design, and improved development of its promising new stration of this technology in the development and demonstration durability rotary valve concept for IC en- extreme operating conditions of of the required durability and per- gines and was looking for a way F1 provided a mechanism to ad- formance. By late 2000 back to to further develop the technology. dress the industry’s prejudice. back testing with the poppet valve The automotive industry, having In 1997 Bishop started work- single cylinder engine demon- observed a succession of failed at- ing with Ilmor Engineering (later strated a 10% power advantage tempts spanning the last century, Mercedes-Ilmor) to develop their and improved durability. In 2002 no longer believed the rotary rotary valve technology for F1 the first V10 engines using this valve concept was mechanically engines. The initial development technology were built and tested viable. It chose Formula One (F1), was carried out on 300cc single exhaustively. A completely new as the criteria for success was well cylinder bottom ends supplied by V10 engine was designed and matched to inherent advantages Ilmor at Bishop’s premises in Syd- manufactured in 2003. -

What Hetman Do I Need?

What Hetman Do I Need? French Horn Trumpet Trombone Tuba Euphonium Baritone #1 Light Piston Schmidt-wrap piston valves* piston valves* piston valves* piston valves* piston valves with little wear horns* #2 Piston Schmidt-wrap piston valves piston valves piston valves piston valves piston valves with some wear horns #3 Classic Piston Schmidt-wrap piston valves piston valves piston valves piston valves piston valves with significant wear horns #4 Light Slide Oil 1st and 3rd slides with little wear valve slide #5 Slide Oil 1st and 3rd slides with some wear valve slide #6 Heavy Slide Oil 1st and 3rd slides with significant wear valve slide #6.5 Light Slide Gel tuning slides tuning slides tuning slides tuning slides tuning slides tuning slides slides with little wear #7 Slide Gel tuning slides tuning slides tuning slides tuning slides tuning slides tuning slides slides with some wear #8 Premium Slide Grease tuning slides tuning slides tuning slides tuning slides tuning slides tuning slides slides with significant wear #9 Ultra Slide Grease vintage horns with corroded slide tuning slides tuning slides tuning slides tuning slides tuning slides tuning slides tubes that might split or crack * #1 can be used instead of #11 or #12 in brand-new rotary valves with extremely tight clearances. French Horn Trumpet Trombone Tuba Euphonium Baritone #11 Light Rotor Oil rotary valves rotary valves rotary valves rotary valves rotary valves with little wear #12 Rotor Oil rotary valves rotary valves rotary valves rotary valves rotary valves with some wear #13 -

ENRESO WORLD - Ilab

ENRESO WORLD - ILab Different Car Engine Types Istas René Graduated in Automotive Technologies 1-1-2019 1 4 - STROKE ENGINE A four-stroke (also four-cycle) engine is an internal combustion (IC) engine in which the piston completes four separate strokes while turning the crankshaft. A stroke refers to the full travel of the piston along the cylinder, in either direction. The four separate strokes are termed: 1. Intake: Also known as induction or suction. This stroke of the piston begins at top dead center (T.D.C.) and ends at bottom dead center (B.D.C.). In this stroke the intake valve must be in the open position while the piston pulls an air-fuel mixture into the cylinder by producing vacuum pressure into the cylinder through its downward motion. The piston is moving down as air is being sucked in by the downward motion against the piston. 2. Compression: This stroke begins at B.D.C, or just at the end of the suction stroke, and ends at T.D.C. In this stroke the piston compresses the air-fuel mixture in preparation for ignition during the power stroke (below). Both the intake and exhaust valves are closed during this stage. 3. Combustion: Also known as power or ignition. This is the start of the second revolution of the four stroke cycle. At this point the crankshaft has completed a full 360 degree revolution. While the piston is at T.D.C. (the end of the compression stroke) the compressed air-fuel mixture is ignited by a spark plug (in a gasoline engine) or by heat generated by high compression (diesel engines), forcefully returning the piston to B.D.C. -

Trumpet Cornet Pocket Trumpet Trumpet Cornet Pocket Trumpet

TrumpetTrumpet CornetCornet PocketPocket TrumpetTrumpet Owner’s Manual Precautions 2 After Playing 8~11 Maintenance goods 2 1. Valve Slide Maintenance 8 Nomenclature 3 2. Maintenance for Pistons and Valve Caings 10 Before playing 4~7 3. Body Maintenance 11 1. Applying Oil to the Piston 4 Others 12 2. Setting the Mouthpiece 5 1. Caution for Strage 12 3. Holding the Instrument 5 2. Cleaning the Instrument 12 4. Press the Pistons 6 Fingering chart 14~15 5. Placing the Instrument 7 6. Tuning 7 Thank you for purchasing “J. Miachael” instrument. For instructions on the proper assembly Nomenclature of the instruments, and how to keep the instruments in optimum condition for as long as possible, we urge you to read this Owner’s manual thoroughly. The precautions given below concern the proper and safe use of the instrument, and are to ●Trumpet 1st Valve Bell protect you and others from any damage or injuries. Please follow and obey these 2nd Valve precautions. Valve Cap 3rd Valve Mouthpiece Caution Mouthpiece Receiver Main Tuning Slide ●Keep the oil, small parts, etc., out of ●Do not throw or swing the instrument. 1st Valve Slide Water Key children’s mouths and do maintenance The mouthpiece or other parts may fall 2nd Valve Slide Stopper Screw when children are not present. off hitting other people. 3rd Valve Slide Valve Casing Bottom Cap ●Take care not to disfigure the instrument. ●Do not modify the instrument. Besides Placing the instrument where it is voiding the warranty, modification of the unstable may cause the instrument to fall instrument may make repairs impossible. -

Supplies Breakdown at a Glance!

Supplies Breakdown At A Glance! Please refer to the Stevensville Bands Handbook for more detailed information. Required Accessories • Binder with plastic sheets • Band folder (provided) • Band instrument (see rentals/Mr. P) • Tuner device (non-phone app strongly recommended) Instrument Supplies (All can be purchased from the band store) Brass (all need mouthpiece) - Trumpet: valve oil, slide grease - French Horn: rotary oil, slide grease - Trombone: slide lubricant, pocket sprayer - Euphonium: valve oil, slide grease - Tuba: valve/rotary oil, slide grease Woodwind (all need mouthpiece sans flute) - Flute: cleaning rod/cloth, pad saver - Oboe: costly reeds, cleaning swab - Clarinet: reeds, cleaning swab - Bass Clarinet: reeds, cleaning swab - Bassoon: costly reeds, cleaning swab - Saxophone: reeds, pad saver - Tenor Saxophone: reeds, pad saver - Bari Saxophone: costly reeds Percussion (home keyboard instrument optional) - Snare: SD-1 General stick, practice pad (optional) - Mallets: optional but preferred for marimba (solo focus) Instrument Checkout and Accessory Information • Students must fill out a “School Instrument Checkout Form” • Each instrument has accessory equipment (listed above) that can be purchased through the band department or online (wwbw.com, amazon.com) (Please contact Mr. Paulus with questions) • Students must bring pencils to class every day • Original copies of sheet music are school property and must be respected • Lost or mistreated equipment may be charged to the student responsible • If an instrument is not yours, you should not be touching it without approval . -

Small Engine Technology Conference

1 r A55OCIAZIONf Tfr NjOA WIL AuTOMOBllf Sczione Toscana INTERNATIONAL SETC SMALL ENGINE TECHNOLOGY CONFERENCE UNDER THE PATRONAGE OF University of Pisa on its 650th Anniversary since the foundation WITH THE PATRONAGE OF Federation Internationale des Societes des Ingenieurs et Techniciens de 1'Automobile WITH THE SUPPORT OF: The Institution of Mechanical Engineers • Automobile Division Ufl Societe des Ingenieurs de l'Automobile Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche Progetto Finalizzato Trasporti 2 December 1-3, 1993 PALAZZO DEI CONGRESSI Via Matteotti, 1 UB/TIB Hannover 89 PISA- ITALY 111 743 354 XII CONTENTS Paper No. Page No. 931471 1 L I TORIELLO - Mercury Marine Division of Brunswick Corp. - Fond du Lac (USA) The green environment and its impact on the recreational marine industry 931472 17 M YAMANOUCHI - Mazda Motor Corp. - Hiroshima (Japan) Automotive engines; the search for environmental harmony 931473 27 G P BLAIR - The Queen's University of Belfast (Northern Ireland) The consumer, the environment and the small engine 931474 31 B BREUER, J PRACKEL, M SCHMIEDER, A WEIDELE - Darmstadt University (Germany) Motorcycle/Rider/Road - Complex and demanding interfaces 931475 41 C CAPUTO - Universita di Roma La Sapienza (Italy) What novelties can be applied to small I.C. engines ? 931477 61 C STAN - College of Technology and Economics - Zwickau (Germany) Concepts for the development of two stroke engines 931478 71 G MONNIER, P DURET - Institut Francais du Petrole - Rueil Malmaison (France) R PARDINI, M NUTI - Piaggio V.E. - Pontedera (Italy) -

June 2021 ITG Journal

International Trumpet Guild® Journal to promote communications among trumpet players around the world and to improve the artistic level of performance, teaching, and literature associated with the trumpet June 2021 ITG Journal The International Trumpet Guild® (ITG) is the copyright owner of all data contained in this file. ITG gives the individual end-user the right to: • Download and retain an electronic copy of this file on electronic devices for the sole use of the end-user • Print a single copy of this file • Quote fair-use passages of this file in not-for-profit research papers as long as the ITG Journal, date, and page number are cited as the source. The International Trumpet Guild®, under the umbrella of United States and international copyright laws, prohibits the following without prior writ ten permission from the Publications Editor of the ITG: • Duplication or distribution of this file or its contents in any manner that does not conform with the uses as stated above • Alteration of this file or the data contained herein • Placement of this file on any web site, server, or any other database or device that allows for the accessing or copying of this file or the data contained herein by any party, including such a device intended to be used wholly within an institution. By scrolling past this page you agree to the fair use guidelines stated above. http://www.trumpetguild.org This cover sheet must accompany this file. The removal of this information is strictly prohibited and can result in expulsion from the organization and legal action. -

Kawasaki KS-125

Cycle Testl • Most new dirt riders begin on a 125. has tractable low-end power for easy Kawasaki’s F-6 blistered competition in However logical this starting point to learning, and the engine is peppy enough the power department, but the thing berm-bouncing may be, there are some at higher revs so that the owner can grow belched noise and sowed hydrocarbons. pitfalls. Thick-wallet types who can afford into faster riding without outgrowing his So Kawasaki melted all their F-6 tooling the best often equate price to suitability motorcycle. Its engine aad handling mix and built the KS-125 from scratch. and end up with a specialized near-racer is almost good enough to keep an expe Kawasaki’s stateside R & D facility in in the Penton/Monark/Rickman family. rienced dirt wizard from dreaming of a Santa Ana. Calif., handled the final pro For beginners, these bikes can be more Penton or Can-Am. totype development of the KS. This divi intimidating than pleasing. The average The KS does nothing exceptionally well, sion had just completed a similar job (with guy will buy a Japanese enduro. He may but it does everything with relentless ade tremendous success) with the Z-l street wind up with a heavy electric-starting quacy. This singular lack of faults makes bike—and the American and Japanese R Yamaha that he finds cumbersome. His the bike seem even better than it actually & D staff eagerly went to work on the MT-series Honda won't have enough is. Nice as the KS feels, several specialized 125 off-road scooter.