Download The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing for Productivity in the Hospitality Industry © Robert Christie Mill

Managing for Productivity in the Hospitality Industry © Robert Christie Mill This work is licensed under a Creative Commons-ShareAlike 4.0 International License Contents About the author ............................................................................................................1 Robert Christie Mill ..................................................................................................................1 Preface .............................................................................................................................2 Why should we be concerned about productivity and what can we do about it?............2 How do we hire productive employees? ...............................................................................3 How can workplaces and jobs be designed to maximize employee productivity? .........3 How can employees be motivated to be productive? ..........................................................4 Chapter 1 Defining productivity ...................................................................................7 1.1 The challenges of productivity ..........................................................................................7 Impact on the hospitality industry .................................................................................7 Life cycle of the hospitality industry ..............................................................................7 Nature of the industry .....................................................................................................8 -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

PATHWAYS INTO POVERTY Lived Experiences Among LGBTQ People

RESEARCH THAT MATTERS PATHWAYS INTO POVERTY Lived Experiences Among LGBTQ People September 2020 Bianca D.M. Wilson Alexandra-Grissell H. Gomez Madin Sadat Soon Kyu Choi M. V. Lee Badgett Pathways into Poverty: Lived Experiences Among LGBTQ People | 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY More than a decade of empirical research has shown that LGBT people in the United States experience poverty at higher rates compared to cisgender heterosexual people.1 More recently, research has also shown that transgender people and cisgender bisexual women experience the highest rates of economic insecurity.2 In response to this knowledge, numerous advocacy and direct services organizations have worked to identify public policies and interventions that can address the high rates of poverty among sexual and gender minority people. However, there is very little research to support any claims about why poverty is so prevalent among LGBT people. Without greater specification of the causes of poverty and the factors affecting the experience of poverty, policies and services may be using less effective mechanisms for alleviating economic insecurity. In the interest of informing the ongoing dialogue about how sexual orientation and gender identity relate to poverty, we designed this study to document experiences with poverty, including factors leading to and maintaining economic insecurity among LGBTQ people. This report is one of several that will be developed from the data collected in the Pathways to Justice Project. The Pathways Project aimed to document updated figures on the national and state-by-state rates of LGBT poverty and explore the experiences and needs of LGBTQ adults living in poverty. As part of this project, we conducted in-person interviews with 93 LGBTQ people in Los Angeles County (n = 60) and Kern County (n = 33) with low incomes or other indicators of economic instability. -

'Zombie' Homes by Jim Redden January 4, 2018 Mayor Says Cost, Complexity Force Other Solutions but Might Consider More Reforms to Program Pushed by Predecessor

The Portland Tribune Wheeler Pauses Hales Campaign to Foreclose on 'Zombie' Homes By Jim Redden January 4, 2018 Mayor says cost, complexity force other solutions but might consider more reforms to program pushed by predecessor. Portland used the threat of foreclosure to force scofflaw landlords to take responsibility for 10 derelict properties over the past 18 months. But the City Council did not approve any others for foreclosure in all of 2017, despite pledging to routinely review potential new ones. The reversal happened after former Mayor Charlie Hales — who pushed the council to crack down harder on "zombie" homes — left office. His successor, Mayor Ted Wheeler, doesn't consider foreclosures a high priority. "The obstacles for government to take away someone's property are formidable," says Wheeler, who took office last January. "It's a very expensive, multiyear process. I'm not sure that's the best use of our resources." The change essentially leaves the enforcement system where it was before the council approved Hales' June 2016 reforms aimed at cracking down on zombie homes, which often sit empty and are a blight on neighborhoods. The Bureau of Development Services, which inspects and cites substandard properties for code violations, maintains a list of hundreds of the worst properties in the city. When BDS cannot convince landlords to pay their fines and fix them up, it can refer them to the City Auditor's Office, which tries again. When the auditor runs out of options, properties can be referred to the council to be approved for foreclosure. If the council agrees, the property is sent to the city treasurer, who schedules a foreclosure auction. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

THE PARENT INSIDER July 2016

Volume 2, Issue 7 THE PARENT INSIDER July 2016 Faith Fellowship Church, 6734 Bridgetown Rd. Cincinnati, OH 45248 513 - 598- 6 7 3 4 Values Are Your Most Important Parenting Tool By Stanton L. and Brenda B. Jones Think of all the different things one ous sexual relationships. A young teen- -Study from U of Virginia can value, good and bad, as ways to ager, despairing of real purpose for her get the acceptance and love we need: life, tries to fill this gaping void with Men who attend reli- gious services regular- communication, beauty, vivacious- slavish conformity to her peer group. ly are more likely to ness, domination, going along with the The kinds of goals we work toward have happy and stable crowd, superficiality, politeness, hu- range from the grandiose to the pa- marriages, more likely mor, seductiveness, honesty, sexual thetic. One person yearns to be Presi- to be involved with conquest. And any of the following and dent or to possess a million dollars by their children and less more can be thought of as ways to age forty. Another lives day to day try- likely to divorce achieve significance: punctuality, work- ing desperately to avoid criticism that Percentage of children living in father-absent aholism, diligence, wealth, power, de- would be devastating, or to receive the homes rose from 11 ceit, frugality, competitiveness, preci- approval of others who are seen as percent in 1960 to 27 sion, evasion of responsibility. One per- respected and esteemed. percent in 2000 son develops an unspoken plan for 38.5 percent of achieving significance by compulsive babies in 2006 were work habits that will force his supervi- born out of wedlock sors to respect him; another attempts to meet the deep need for relatedness Article continued on Pgs 4. -

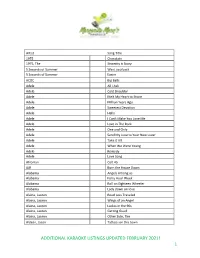

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

Country Airplay; Brooks and Shelton ‘Dive’ In

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS JUNE 24, 2019 | PAGE 1 OF 19 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Thomas Rhett’s Behind-The-Scenes Country Songwriters “Look” Cooks >page 4 Embracing Front-Of-Stage Artist Opportunities Midland’s “Lonely” Shoutout When Brett James sings “I Hold On” on the new Music City Puxico in 2017 and is working on an Elektra album as a member >page 9 Hit-Makers EP Songs & Symphony, there’s a ring of what-ifs of The Highwomen, featuring bandmates Maren Morris, about it. Brandi Carlile and Amanda Shires. Nominated for the Country Music Association’s song of Indeed, among the list of writers who have issued recent the year in 2014, “I Hold On” gets a new treatment in the projects are Liz Rose (“Cry Pretty”), Heather Morgan (“Love Tanya Tucker’s recording with lush orchestration atop its throbbing guitar- Someone”), and Jeff Hyde (“Some of It,” “We Were”), who Street Cred based arrangement. put out Norman >page 10 James sings it with Rockwell World an appropriate in 2018. gospel-/soul-tinged Others who tone. Had a few have enhanced Marty Party breaks happened their careers with In The Hall differently, one a lbu ms i nclude >page 10 could envision an f o r m e r L y r i c alternate world in Street artist Sarah JAMES HUMMON which James, rather HEMBY Buxton ( “ S u n Makin’ Tracks: than co-writer Daze”), who has Riley Green’s Dierks Bentley, was the singer who made “I Hold On” a hit. done some recording with fellow songwriters and musicians Sophomore Single James actually has recorded an entire album that’s expected under the band name Skyline Motel; Lori McKenna (“Humble >page 14 later this year, making him part of a wave of writers who are and Kind”), who counts a series of albums along with her stepping into the spotlight with their own multisong projects. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Karaoke Version Song Book

Karaoke Version Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID (Hed) Planet Earth 50 Cent Blackout KVD-29484 In Da Club KVD-12410 Other Side KVD-29955 A Fine Frenzy £1 Fish Man Almost Lover KVD-19809 One Pound Fish KVD-42513 Ashes And Wine KVD-44399 10000 Maniacs Near To You KVD-38544 Because The Night KVD-11395 A$AP Rocky & Skrillex & Birdy Nam Nam (Duet) 10CC Wild For The Night (Explicit) KVD-43188 I'm Not In Love KVD-13798 Wild For The Night (Explicit) (R) KVD-43188 Things We Do For Love KVD-31793 AaRON 1930s Standards U-Turn (Lili) KVD-13097 Santa Claus Is Coming To Town KVD-41041 Aaron Goodvin 1940s Standards Lonely Drum KVD-53640 I'll Be Home For Christmas KVD-26862 Aaron Lewis Let It Snow, Let It Snow, Let It Snow KVD-26867 That Ain't Country KVD-51936 Old Lamplighter KVD-32784 Aaron Watson 1950's Standard Outta Style KVD-55022 An Affair To Remember KVD-34148 That Look KVD-50535 1950s Standards ABBA Crawdad Song KVD-25657 Gimme Gimme Gimme KVD-09159 It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas KVD-24881 My Love, My Life KVD-39233 1950s Standards (Male) One Man, One Woman KVD-39228 I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus KVD-29934 Under Attack KVD-20693 1960s Standard (Female) Way Old Friends Do KVD-32498 We Need A Little Christmas KVD-31474 When All Is Said And Done KVD-30097 1960s Standard (Male) When I Kissed The Teacher KVD-17525 We Need A Little Christmas KVD-31475 ABBA (Duet) 1970s Standards He Is Your Brother KVD-20508 After You've Gone KVD-27684 ABC 2Pac & Digital Underground When Smokey Sings KVD-27958 I Get Around KVD-29046 AC-DC 2Pac & Dr.