Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: a Routine Activity Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Song of the Year

General Field Page 1 of 15 Category 3 - Song Of The Year 015. AMAZING 031. AYO TECHNOLOGY Category 3 Seal, songwriter (Seal) N. Hills, Curtis Jackson, Timothy Song Of The Year 016. AMBITIONS Mosley & Justin Timberlake, A Songwriter(s) Award. A song is eligible if it was Rudy Roopchan, songwriter songwriters (50 Cent Featuring Justin first released or if it first achieved prominence (Sunchasers) Timberlake & Timbaland) during the Eligibility Year. (Artist names appear in parentheses.) Singles or Tracks only. 017. AMERICAN ANTHEM 032. BABY Angie Stone & Charles Tatum, 001. THE ACTRESS Gene Scheer, songwriter (Norah Jones) songwriters; Curtis Mayfield & K. Tiffany Petrossi, songwriter (Tiffany 018. AMNESIA Norton, songwriters (Angie Stone Petrossi) Brian Lapin, Mozella & Shelly Peiken, Featuring Betty Wright) 002. AFTER HOURS songwriters (Mozella) Dennis Bell, Julia Garrison, Kim 019. AND THE RAIN 033. BACK IN JUNE José Promis, songwriter (José Promis) Outerbridge & Victor Sanchez, Buck Aaron Thomas & Gary Wayne songwriters (Infinite Embrace Zaiontz, songwriters (Jokers Wild 034. BACK IN YOUR HEAD Featuring Casey Benjamin) Band) Sara Quin & Tegan Quin, songwriters (Tegan And Sara) 003. AFTER YOU 020. ANDUHYAUN Dick Wagner, songwriter (Wensday) Jimmy Lee Young, songwriter (Jimmy 035. BARTENDER Akon Thiam & T-Pain, songwriters 004. AGAIN & AGAIN Lee Young) (T-Pain Featuring Akon) Inara George & Greg Kurstin, 021. ANGEL songwriters (The Bird And The Bee) Chris Cartier, songwriter (Chris 036. BE GOOD OR BE GONE Fionn Regan, songwriter (Fionn 005. AIN'T NO TIME Cartier) Regan) Grace Potter, songwriter (Grace Potter 022. ANGEL & The Nocturnals) Chaka Khan & James Q. Wright, 037. BE GOOD TO ME Kara DioGuardi, Niclas Molinder & 006. -

Marxman Mary Jane Girls Mary Mary Carolyne Mas

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red 12 Dec 98 Take Me There (Blackstreet & Mya featuring Mase & Blinky Blink) 7 9 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. 10 Jul 99 Get Ready 32 4 20 Nov 04 Welcome Back/Breathe Stretch Shake 29 2 MARXMAN Total Hits : 8 Total Weeks : 45 Anglo-Irish male rap/vocal/DJ group - Stephen Brown, Hollis Byrne, Oisin Lunny and DJ K One 06 Mar 93 All About Eve 28 4 MASH American male session vocal group - John Bahler, Tom Bahler, Ian Freebairn-Smith and Ron Hicklin 01 May 93 Ship Ahoy 64 1 10 May 80 Theme From M*A*S*H (Suicide Is Painless) 1 12 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 5 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 12 MARY JANE GIRLS American female vocal group, protégées of Rick James, made up of Cheryl Ann Bailey, Candice Ghant, MASH! Joanne McDuffie, Yvette Marine & Kimberley Wuletich although McDuffie was the only singer who Anglo-American male/female vocal group appeared on the records 21 May 94 U Don't Have To Say U Love Me 37 2 21 May 83 Candy Man 60 4 04 Feb 95 Let's Spend The Night Together 66 1 25 Jun 83 All Night Long 13 9 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 3 08 Oct 83 Boys 74 1 18 Feb 95 All Night Long (Remix) 51 1 MASON Dutch male DJ/producer Iason Chronis, born 17/1/80 Total Hits : 4 Total Weeks : 15 27 Jan 07 Perfect (Exceeder) (Mason vs Princess Superstar) 3 16 MARY MARY Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 16 American female vocal duo - sisters Erica (born 29/4/72) & Trecina (born 1/5/74) Atkins-Campbell 10 Jun 00 Shackles (Praise You) -

City Youths Paint Fire Hydrants Centre Party Center in Westlake

SPORTS MENU TIPS ‘Stuff The Bus’ to accept donations Kid’s Corner BW to hold MBA open house Stuff the Bus for Cleveland’s Kids will hold its There will be an MBA Open House at B-W annual shoes, clothing, school supply fund drive to ben- Darian Van Horn, who is East, Landmark Centre, 25700 Science Park Dr. (Suite efit Greater Cleveland’s children in need during the back the son of Belinda Lemon, is 11 100) on Wednesday, August 15, at 6 p.m. Participants can Boxers Compete Handy Snack Bubbling to school season on Friday, August 17 from 10 a.m. to 6 speak with faculty to learn more about B-W’s MBA pro- At Olympic Trials With Blueberries p.m. at Great Northern Mall Parking Lot, North Olmsted. A months old. He has a lovely smile grams. Practical, principled and powerful, a B-W MBA school bus will be parked in the mall parking lot and volun- and likes cooing as well as playing combines sound theory and practical application to pro- teers will be on hand to accept donations. People can take vide work-relevant learning for tomorrow’s business lead- a chance to win prices with the WDOK Fifth Third Bank with his squeaky toy. Darian has ers. For reservations or info., e-mail [email protected] or See Page 8 See Page 9 Mega Money Machine. For information, visit www.sc4k. three brothers and one sister. call(440) 826-2390 or (800) 773-4261. Register online, at org or call (216) 881-SHOE (7463) x. -

Digest of Criminal Laws 2019

D I DIGEST G OF E CRIMINAL S T LAWS A service of the Maryland Police and Correctional Training Commissions Albert L. Liebno, Acting Executive Director Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services Robert L. Green, Secretary State of Maryland Larry, Hogan, Governor Boyd K. Rutherford, Lt. Governor 2 0 1 REVISED OCTOBER 1, 2019 Printed on Recycled Paper 9 DIGEST OF CRIMINAL LAWS October 1, 2019 Distributed by: Maryland Police and Correctional Training Commissions 6852 4th Street Sykesville, Maryland 21784 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Useful Phone and Contact Information ..................................7 II. General Police Powers ..............................................................9 Arrest – Authority .......................................................................9 Authority of Federal Law Enforcement Officers ................10 Authority of Police Officers .................................................9 Charging by Citation ..........................................................10 Definition: Distinction Between Felony Arrests and Misdemeanor Arrests ..........................................................9 Exemptions from Arrest ......................................................10 Arrest Powers and Other Authority – Miscellaneous Officer ...18 Authority of Officers of Other States to Arrest in Maryland – Fresh Pursuit ...............................................22 Authority of Parole and Probation Agents ..........................18 Humane Society Officers Arrest Powers – Cruelty ............22 Military -

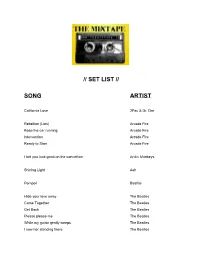

the Mixtape // Set List

// THE MIXTAPE // SET LIST SONG ARTIST Rebellion (Lies) Arcade Fire Keep the car running Arcade Fire Intervention Arcade Fire Ready to Start Arcade Fire I bet you look good on the dancefloor Arctic Monkeys Do I wanna know? Arctic Monkeys Shining Light Ash Pompeii Bastille Hide your love away The Beatles Come Together The Beatles Get Back The Beatles Please please me The Beatles While my guitar gently weeps The Beatles I saw her standing there The Beatles A Day in the Life The Beatles All you need is love The Beatles Day tripper The Beatles Helter Skelter The Beatles Strawberry Fields The Beatles St. Andrews Bedouin Soundclash Eve, the apple of my eye Bell X1 Catch My Disease Ben Lee Hyperballad Bjork All the small things Blink 182 I miss you Blink 182 Banquet Bloc Party The Prayer Bloc Party Uniform Bloc Party Positive Tension Bloc Party Girls & Boys Blur The Universal Blur All Along the Watchtower Bob Dylan Knocking on Heaven’s Door Bob Dylan Lay Lady Lay Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone Bob Dylan Shelter From the Storm Bob Dylan Times are a changing Bob Dylan Desolation Row Bob Dylan Livin on a prayer Bon Jovi Dead or Alive Bon Jovi More Than A Feeling Boston There is Box Car Racer Soco Amaretto Lime Brand New The quiet things that no one ever knows Brand New Jesus Brand New You Won't Know Brand New Okay I believe you... Brand New Not the sun Brand New Anthems for a 17 year old girl Broken Social Scene Born to Run Bruce Springsteen I’m on Fire Bruce Springsteen Secret Garden Bruce Springsteen Streets of Philadelphia Bruce Springsteen The -

Damien Rice Gig Review with the Lights Dimmed in a Glorified Library

Damien Rice Gig Review With the lights dimmed in a glorified library, the diminutive figure of Damien Rice warbles away in the corner of the Michelberger lobby in which he’s been crammed into. This however is not due to the insignificance of the event, rather the fact they couldn’t fit anymore Rice fans in if they tried. Once again Rice has found himself trying to perform in a setting that is cosy and intimate, performing to a small audience that he believes is probably the only group of people capable of understanding his simple yet raw music and demeanour… Rice has forgotten again though, forgotten he is a superstar, one of, if not the greatest acoustic singersongwriter of music’s modern era. Opening with the ever so tangible ‘Delicate’, any fears of Rice just performing songs from his new album disappear the audience has been treated to a timeless classic from ‘O’. Delivered with the esoteric aura which seems to have followed Rice throughout his 16 year long solo career, He then delves straight into ‘Volcano’ where he bellows the lyrics “What i really need is what makes me bleed”. This is true of Damien Rice, he always shines through adversity. Ever the profound philosopher, debut album ‘O’ graced our ears after some soul searching in Italy, a result of previous rock group ‘Juniper’s failure to really take off. This is the first album Rice has released now without the help of the angelic Lisa Hannigan. Rice’s ego would never admit the harm this would potentially cause to his music and live performances, but surely it did. -

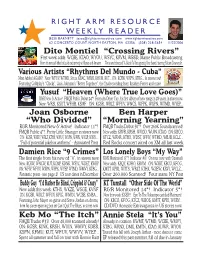

Right Arm Resource 061122.Pmd

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE WEEKLY READER JESSE BARNETT [email protected] www.rightarmresource.com 62 CONCERTO COURT, NORTH EASTON, MA 02356 (508) 238-5654 11/22/2006 Dito Montiel “Crossing Rivers” First week adds: WCBE, KTAO, WYOU, WSYC, KRVM, WBSD, Maine Public Broadcasting From his new self-titled cd, sold exclusvively at iTunes and Amazon Wrote and directed “A Guide To Recognizing Your Saints” starring Robert Downey Jr. Various Artists “Rhythms Del Mundo - Cuba” Most Added AGAIN! New: WFUV, WTMD, Sirius, KBAC, WBJB, KHUM, KUT... ON: KCRW, WXPN, KTBG... In stores now! Featuring Coldplay’s “Clocks”, Jack Johnson’s “Better Together”, the final recording from Ibrahim Ferrer and more Yusuf “Heaven (Where True Love Goes)” R&R New & Active! FMQB Public Debut 24*! From An Other Cup, his first album of new songs in 28 years, in stores now New: WRSI, KSUT, WFHB, KSMF ON: KGSR, WRLT, WFUV, WNCS, WFPK, WXPN, WTMD, WYEP... Joan Osborne Ben Harper “Who Divided” “Morning Yearning” R&R Monitored New & Active! Indicator 11*! FMQB Tracks Debut 50*! Over 260K Soundscanned! FMQB Public 4*! Pretty Little Stranger in stores now New adds: KRVB, KRSH, WVOD, WUIN, KTAO ON: KBCO, O N: KGSR, WXRV, WRLT, KTHX, WFUV, WXPN, WFPK, WYEP, WXPK... KTCZ, WRNR, KTHX, WDST, WFIV, WTMD, WBJB, KCLC... “Full of potential jukebox anthems” - Associated Press Red Rocks concert aired on XM all last week Damien Rice “9 Crimes” Los Lonely Boys “My Way” The first single from his new cd “9”, in stores now R&R Monitored 15*! Indicator #6! On tour now with Ozomatli New: KCRW, WNCW, KUT, KCMP, KDNK, WSYC, WDET, KWRP New adds: KSQY, KOHO, KBOM ON: WXRT, KBCO, KFOG, ON: WFIV, WFUV, WXPN, WFPK, WYEP, WTMD, WMVY, KTBG.. -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Title 1985 Bowling For Soup 2002 Anne-Marie 1 2 3 Len Berry 1 2 3 4 Feist 1 2 3 4 Sumpin New Coolio 17 (Seventeen) Mk 18 Till I Die Bryan Adams 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin 2 4 6 8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 2 Become 1 Jewel 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 2 Find U Jewel 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden 20th Century Boy T Rex 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 24 Hour Party People Happy Mondays 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 24 Hours From You Next Of Kin 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash 26 Cents Wilkinsons 48 Crash Suzi Quatro 5 4 3 2 1 Manfred Mann 6 Underground Sneaker Pimps 6345 789 Blues Brothers 68 Guns Alarm 7 Ways Abs 74 75 Connells 9 Crimes Damien Rice 99 Red Balloons Nena A and E Goldfrapp A Bad Dream Keane A Better Man Robbie Williams A Better Man Thunder A Big Hunk Of Love Elvis Presley A Boy From Nowhere Tom Jones A Brand New Me Dusty Springfield A Day In The Life Beatles A Deeper Love Aretha Franklin A Design For Life Manic Street Preachers A Different Corner George Michael A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley A Girl Like You Edwin Collins A Girl's Gotta Do Mindy Mccready A Good Heart Fergal Sharkey A Good Hearted Woman Waylon Jennings A Good Tradition Tinita Tikaram A Groovy Kind Of Love Mindbenders A Groovy Kind Of Love Phil Collins A House Is Not A Home Brook Benton A Kind Of Magic Queen A Kiss Is A Terrible Thing To Waste Meatloaf updated: March 2021 www.djdanblaze.com Can't Find one? Just ask DJ Dan Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Title A Kiss Is A Terrible Thing To Waste Meatloaf A Little Bit -

Using the Structure of Dbpedia for Exploratory Search

Using the Structure of DBpedia for Exploratory Search Samantha Lam Conor Hayes DERI, NUI Galway DERI, NUI Galway IDA Business Park, Lower Dangan IDA Business Park, Lower Dangan Galway, Ireland Galway, Ireland [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT semantic graph and as such the links can be used to infer Recently there has been much work in defining similarity between entities, e.g. for musicians in DBpedia, similarity on heterogeneous networks in a super- there is a link type called AssociatedActs, as well as Record- vised manner, using prescribed patterns based Label. These links show that there are relationships between on the network schema. However, there is also the musician and another musician, and between the musi- a wealth of data that doesn't ascribe rigidly to cian and its record label, but these are clearly two different fixed schemas, such as DBpedia. In this work relationships. Past methods also tended to focus solely on we explore the idea of using DBpedia for com- one ontology e.g. the Wikipedia Category [22], or when util- puting semantic relatedness in the context of an ising the Resource Description Framework (RDF), not use exploratory search. We first analyse the main a graph-based model [15, 21]. These methods are useful for datasets of DBpedia, as graphs, to assess their queries that have a specific answer, e.g. logical queries for suitability for the task. We then employ a weight- finding answers to questions such as `what year was X per- ing scheme on the Infobox properties graph in- son born in?'. -

Top Songs of the 2000'S.Pages

Top Songs of the 2000ʼs 1. Somebody Told Me - 21. White People For 40. Read My Mind - The The Killers Peace - Against Me! Killers 2. In The End - Linkin 22. I'm Shipping Up to 41. Rooftops - Park Boston - Dropkick Lostprophets 3. Los Angeles is Burning Murphys 42. Maybe Tomorrow - - Bad Religion 23. Falling Down - Stereophonics 4. Headstrong - Trapt Atreyu 43. Far Behind - Social 5. Thrash Unreal - 24. Fix You - Coldplay Distortion Against Me! 25. Knights of Cydonia - 44. Big Casino - Jimmy 6. Viva La Vida - Coldplay Muse Eat World 7. All These Things That 26. Somewhere Else - 45. A Different Kind of I've Done - The Killers Razorlight Pain - Cold 8. One Step Closer - 27. I Believe in a Thing 46. Straight Out of Line - Linkin Park Called Love - The Godsmack 9. The '59 Sound - Darkness 47. Somewhere I Belong Gaslight Anthem 28. Human - The Killers - Linkin Park 10. Mr. Brightside - The 29. Audience of One - 48. We're All To Blame - Killers Rise Against Sum 41 11. Walk Away - 30. America - Razorlight 49. Sex On Fire - Kings of Dropkick Murphys 31. Smokers Outside the Leon 12. Re-Education Hospital Doors - Editors 50. Anthem - Zebrahead (Through Labor) - Rise 32. Island in the Sun - 51. Dashboard - Modest Against Weezer Mouse 13. Munich - Editors 33. Crawling - Linkin 52. Beverly Hills - Weezer 14. Use Somebody - Park 53. Take Me Out - Franz Kings of Leon 34. Who's Gonna Save Ferdinand 15. Clocks - Coldplay Us - The Living End 54. Savior - Rise Against 16. When You Were 35. Sunshine Highway - 55. In the Morning - Young - The Killers Dropkick Murphys Razorlight 17. -

Set List // Song Artist

// SET LIST // SONG ARTIST California Love 2Pac & Dr. Dre Rebellion (Lies) Arcade Fire Keep the car running Arcade Fire Intervention Arcade Fire Ready to Start Arcade Fire I bet you look good on the dancefloor Arctic Monkeys Shining Light Ash Pompeii Bastille Hide your love away The Beatles Come Together The Beatles Get Back The Beatles Please please me The Beatles While my guitar gently weeps The Beatles I saw her standing there The Beatles A Day in the Life The Beatles All you need is love The Beatles Day tripper The Beatles Helter Skelter The Beatles Rock and Roll Music The Beatles St. Andrews Bedouin Soundclash Eve, the apple of my eye Bell X1 Rocky Took a Lover Bell X1 Catch My Disease Ben Lee Crazy in Love Beyonce & Jay Z Hyperballad Bjork All the small things Blink 182 I miss you Blink 182 Banquet Bloc Party The Prayer Bloc Party Uniform Bloc Party Positive Tension Bloc Party Hanging on the Telephone Blondie Girls & Boys Blur The Universal Blur All Along the Watchtower Bob Dylan Knocking on Heaven’s Door Bob Dylan Lay Lady Lay Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone Bob Dylan Shelter From the Storm Bob Dylan Times are a Changin’ Bob Dylan Livin’ on a prayer Bon Jovi Dead or Alive Bon Jovi More Than A Feeling Boston There is Box Car Racer Soco Amaretto Lime Brand New The quiet things that no one ever knows Brand New Jesus Brand New You Won't Know Brand New Okay I believe you... Brand New Not the sun Brand New You Stole Brand New Anthems for a 17 year old girl Broken Social Scene Born to Run Bruce Springsteen I’m on Fire Bruce Springsteen