The Clock Tower

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief History of the Great Clock at Westminster Palace

A Brief History of the Great Clock at Westminster Palace Its Concept, Construction, the Great Accident and Recent Refurbishment Mark R. Frank © 2008 A Brief History of the Great Clock at Westminster Palace Its Concept, Construction, the Great Accident and Recent Refurbishment Paper Outline Introduction …………………………………………………………………… 2 History of Westminster Palace………………………………………………... 2 The clock’s beginnings – competition, intrigues, and arrogance …………... 4 Conflicts, construction and completion …………………………………….. 10 Development of the gravity escapement ……………………………………. 12 Seeds of destruction ………………………………………………………….. 15 The accident, its analysis and aftermath …………………………………… 19 Recent major overhaul in 2007 ……………………………………………... 33 Appendix A …………………………………………………………………... 40 Footnotes …………………………………………………………………….. 41 1 Introduction: Big Ben is a character, a personality, the very heart of London, and the clock tower at the Houses of Parliament has become the symbol of Britain. It is the nation’s clock, instantly recognizable, and brought into Britain’s homes everyday by the BBC. It is part of the nation’s heritage and has long been established as the nation’s timepiece heralding almost every broadcast of national importance. On the morning of August 5th 1976 at 3:45 AM a catastrophe occurred to the movement of the great clock in Westminster Palace. The damage was so great that for a brief time it was considered to be beyond repair and a new way to move the hands on the four huge exterior dials was considered. How did this happen and more importantly why did this happen and how could such a disaster to one of the world’s great horological treasures be prevented from happening again? Let us first go through a brief history leading up to the creation of the clock. -

Clock Tower STEM in A

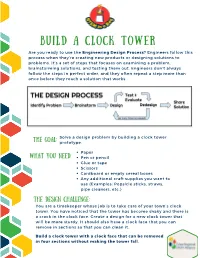

build a clock tower Are you ready to use the Engineering Design Process? Engineers follow this process when they’re creating new products or designing solutions to problems. It’s a set of steps that focuses on examining a problem, brainstorming solutions, and testing them out. Engineers don’t always follow the steps in perfect order, and they often repeat a step more than once before they reach a solution that works. The Goal: Solve a design problem by building a clock tower prototype. Paper what you need: Pen or pencil Glue or tape Scissors Cardboard or empty cereal boxes Any additional craft supplies you want to use (Examples: Popsicle sticks, straws, pipe cleaners, etc.) The Design challenge: You are a timekeeper whose job is to take care of your town’s clock tower. You have noticed that the tower has become shaky and there is a crack in the clock face. Create a design for a new clock tower that will be more sturdy. It should also have a clock face that you can remove in sections so that you can clean it. Build a clock tower with a clock face that can be removed in four sections without making the tower fall. build a clock tower CONt. design it Gather all of your materials and examine them. Think about how you might use each of them to build your clock tower. Architects draw blueprints of their buildings before they build them. A blueprint is a drawing of what you want your construction to look like, and it helps you plan how you are going to build something. -

Holy Coverings in the Tareq Rajab Museum the Origin of the Tradition of Covering the Ka'aba with Cloth Is Lost In

About the journal Contents 02 18 April 2011 The Journey to the Centre Aly Gabr 09 9 May 2011 China and the Islamic World: The evidence of 12th and 13th century Northern Syria Martine Muller-Weiner 22 26 September 2011 Holy Coverings in the Tareq Rajab Museum Ziad T Alsayed Rajab 27 17 October 2011 A Brief History of the Ismaili D’awa Adel Salem al-Abdul Jader 31 28 November 2011 The Kingdom of Saba: Current Research by the German Archaeological Institute in South Arabia (Yemen) Iris Gerlach 38 5 December 2011 The Oriental Pearl in the Maritime Trade Annie Montigny 43 13 December 2011 Raili and Reima Pietilä Jarno Paltonen 49 9 January 2012 Islamic Heritage in Bosnia and Herzegovina Kenan Musić This publication is sponsored in part by: LNS 1785 J Fabricated from gold, worked in kundan technique and set with rubies and emeralds Height 9 mm; diameter 100 mm India, Mughal, c. 1st quarter 17th century AD Hadeeth ad-Dar 1 Volume 37 The Journey to the Centre be performed in congregation in a mosque although as opposed to a physical one, meaning that he the whole earth that we know is a potential place for employed his intuition with what he dealt with. the performance of that daily activity. This notion He saw himself as a tripartite being composed of makes the earth a potential vast mosque. body (jism), soul (nafs), and spirit (rouh). Without the union of these three parts he believed he/ I am sure that the question arises in some of she would be demeaned in his/her existence and your minds: does God really expects us to show unbalanced. -

Winding the Harper County Courthouse Clock… We’Ll Assume You Had a Key and Took the Elevator to the 5Th Floor

Winding the Harper County Courthouse Clock… We’ll assume you had a key and took the elevator to the 5th floor. That’s the easy part of the job. Now you start up the steps into the Clock Tower. You go up the first flight of stairs to a landing. The first flight of steps to the landing is the longest flight. Then it is a quick trip up to the Pendulum Room. There isn’t a lot to see in the Pendulum Room. The pendulum itself is enclosed in an unassuming white wooden box. You look past it to the steps up to the clockworks. As you climb the last steps you find the clockworks are enclosed in their own Clock Room, a room in a room. Wondering what you have gotten into, you pry open the door and get your first glimpse of this magnificent machine. You first notice the long wooden pendulum rod sticks through the floor and is really the only piece you see moving. You see lots of gears and cables running through the roof of the room. The cables run to the weights that power the clock. Using the large wood- handled crank, you wind the chime cable on the spool with over 120 turns of the handle. The crank comes off and you move it to the other side of the pendulum rod to wind the clock itself. That usually only takes 20-30 turns, but they are tougher turns. Finished winding, you get the chance to look over the clockworks a little. -

Universal Robots How to Survive in the Robotics Industry As a Software Engineer the Idea Automation for Everybody

Universal Robots How to survive in the Robotics Industry as a Software Engineer The idea Automation for Everybody UR designs and builds revolutionary collaborative robots Perfect for all sizes of business UR products are so user-friendly that anyone can operate them And so affordable that it is worthwhile for anyone to invest in them Low total cost of ownership The idea Robot as a Tool Our robots are made into a tool that can be used by the production staff to help them do their work better. The idea Manual Work Outsourcing High wages Product knowledge disappears Variable quality Copying of product Problems with the Labour Inspectorate THE INDUSTRY BEFORE st 1 Generation Special Industrial Robots Machinery Big investment No flexibility Long start-up period Must be specially designed Limited flexibility The idea Unique potential We are used by small to very large companies – and across industries We create growth and jobs globally Demand for automation is high of all companies globally are SME’s strategy Annual supply of industrial robots 1000 strategy Industrial robots by industry strategy Applications International Overview 2004: The idea 2005: Company founded 2007: First prototype – UR5 2008: First sales 2009: Distribution in DK 2010: European distribution 2011: Distribution in Asia 2012: Entered US and Launch of UR10 2013: Subsidiaries in New York and Shanghai 2014: Office in Spain 2015: Launch of UR 3 and office in Singapore, Universal Robots is acquired by Teradyne for $285M Revenue (million €) 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 E2016 E2017 Global Distribution Network UR Headquarters Universal Robots subdivisions Universal Robots distribution About the Company ~300 Employees 22 Nationalities Offices in 7 Countries Over 300 Distributors 20 International Awards Case stories NASDAQ bell Schunk SDH-hand Cross Automation NASDAQ / Frank Tobe Case stories Teradyne to Buy Universal Robots for $285 Million By Angela Chen The Wall Street Journal May 13, 2015 7:35 a.m. -

Preserving the Tower Clocks at Fort Monroe, Virginia Alan Bomar, VA

Preserving the Tower Clocks at Fort Monroe, Virginia Alan Bomar, VA At Fort Monroe, in Hampton Roads, Virginia, there are two tower clocks that have never been modified from their original installation. This article is intended to bring well-deserved awareness to these clocks. Both are in near-original condition and have never been electrified in any manner. The first one, located in Building 83, the Fort’s Post Office and Customs House, is well documented. It is a Seth Thomas Model 5, dating to 1898, with four dial faces. The second, which has a more mysterious past and predates the other in design, is a Seth Thomas Model 15 striker in Building 5, the post’s main barracks building. Records indicate that it was ordered by the U.S. government for Fort Monroe in the summer of 1880. Both clocks are wound weekly and kept active today by a team of Fort Monroe volunteers. Fort Monroe was a United States Army post that was closed as part of the Base Realignment and Closure Commission (BRAC) in 2011. Today, the fort is managed in partnership with the National Park Service and the Fort Monroe Authority, a political subdivision of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Fig. 1: U.S. Post Office Building built in 1898 at Fort Monroe, VA Fort Monroe is one of many “Third-System” forts built in the 19th century. Construction started on the fort and its surrounding buildings in 1819. It is similar to Fort Adams in Newport, Rhode Island, as both were designed by Simon Bernard and built following the War of 1812, after the Coastal Fortifications Board decided to increase fortifications around the United States. -

Tower Times March 2010 Contents Tower Times U.S

Tower Times March 2010 Contents Tower Times U.S. Army Corps of 3 Message from the Commanding General Engineers Brig. Gen. Michael J. Walsh, Division Commander Rock Island District Vol. 32 No. 6 5 Deployment Proves to be More than a Job March 2010 District Commander 6 Writing Women Back into History Col. Shawn McGinley March is Women’s History Month Chief, Corporate 8 Placing Concrete Underwater Communications Emergency repairs begin at Dresden Island Lock and Dam Ron Fournier Editor 10 Emergency Preparedness: Are you Ready? Hilary Markin This newsletter is an authorized 12 Clock Tower Historic Corridor publication for members of the U.S. Fourth floor renovations and displays nearly complete Army. Contents of the Tower Times are not necessarily official views of, or endorsed by, the U.S. Government, 14 Around the District Department of Defense, Department of the Army, or the Rock Island Dis- trict U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. 15 Spotlight on the District - Kathleen Sullivan It is published monthly using offset press by the Corporate Commu- nications Office, Rock Island District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Clock Tower Building, Box 2004, Rock Island, IL 61204-2004. Phone (309) On the Cover 794-5730. Circulation 1,500. Adam Ziegler (left) and Jason Brown, Engineering and Construction Division, Send articles to Editor, Corporate inspect the pipe transporting concrete Communications Office, U.S. Army from the staging area to the boom truck Corps of Engineers, Clock Tower during a site visit at Dresden Island Building, P.O. Box 2004, Rock Island, Lock and Dam. (See story about Dresden IL, 61204-2004; or e-mail at cemvr- Island on page 8.) [email protected]. -

Time Keeping Experiments for a Mechanical Engineering Education Laboratory Sequence

AC 2009-439: TIME-KEEPING EXPERIMENTS FOR A MECHANICAL ENGINEERING EDUCATION LABORATORY SEQUENCE John Wagner, Clemson University Katie Knaub, National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors Page 14.1271.1 Page © American Society for Engineering Education, 2009 Time Keeping Experiments for a Mechanical Engineering Education Laboratory Sequence Abstract The evolution of science and technology throughout history parallels the development of time keeping devices which assist mankind in measuring and coordinating their daily schedules. The earliest clocks used the natural behavior of the sun, sand, and water to approximate fixed time intervals. In the medieval period, mechanical clocks were introduced that were driven by weights and springs which offered greater time accuracy due to improved design and materials. In the last century, electric motor driven clocks and digital circuits have allowed for widespread distribution of clock devices to many homes and individuals. In this paper, a series of eight laboratory experiments have been created which use a time keeping theme to introduce basic mechanical and electrical engineering concepts, while offering the opportunity to weave societal implications into the discussions. These bench top and numerical studies include clock movements, pendulums, vibration and acoustic analysis, material properties, circuit breadboards, microprocessor programming, computer simulation, and artistic water clocks. For each experiment, the learning objectives, equipment and materials, and laboratory procedures are listed. To determine the learning effectiveness of each experiment, an assessment tool will be used to gather student feedback for laboratory improvement. Finally, these experiments can also be integrated into academic programs that emphasize science, technology, engineering and mathematical concepts within a societal context. -

Mecca Royal Clock Tower Chooses AP Sensing Mecca, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

CASE STUDY Mecca Royal Clock Tower Chooses AP Sensing Mecca, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Project Overview Background The Mecca Royal Clock Tower (also cable as a linear heat detector. • Mecca Royal Clock tower need- known as one of the Abraj Al-Bait The system continuously monitors ed a robust and reliable fire and Towers) is an engineering and archi- thousands of temperature points heat detection system tectural marvel and is located near along the asset in real time, detect- the world’s largest mosque as well ing abnormal heat developments by • Illuminated with over two as Islam’s most sacred site, the Mas- taking the historical data of seasonal million LED lights jid al Haram. It contains the tallest or diurnal temperature changes into hotel, the tallest clock tower, and account. AP Sensing’s technology the largest clock face in the world. has the industry’s lowest false alarm • Harsh climate conditions (direct rate, and provides the information sunlight, cool temperatures at needed so the operator can react night and thermal effects from In addition to the construction quickly in case of an emergency. wind) challenges and intricate workings of the huge clock, the tower is illuminated with 21,000 white and Our LHD system, based on Distrib- Solution & Benefits green lights, and two million LED uted Temperature Sensing (DTS) • Linear Heat Detection (LHD) lights. In order to protect this unique technology, is designed for harsh system for the media wall and infrastructure from overheating or conditions and virtually mainte- the illuminated crescent fire damage, AP Sensing’s Linear nance-free. -

Model of a Mechanical Clock Escapement John Wagner Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints Publications Mechanical Engineering 7-2012 Model of a Mechanical Clock Escapement John Wagner Clemson University, [email protected] David Moline Clemson University Eugene Vold National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/mecheng_pubs Part of the Mechanical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Please use publisher's recommended citation. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mechanical Engineering at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Model of a mechanical clock escapement David Moline Department of Electrical Engineering, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina 29634 John Wagner Department of Mechanical Engineering, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina 29634 Eugene Volk National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors, Western Carolina Chapter #126, 636 Cherokee Terrace, Lake Toxaway, North Carolina 28747 (Received 12 April 2011; accepted 9 April 2012) The mechanical tower clock originated in Europe during the 14th century to sound hourly bells and later display hands on a dial. An important innovation was the escapement mechanism, which converts stored energy into oscillatory motion for fixed time intervals through the pendulum swing. Previous work has modeled the escapement mechanism in terms of inelastic and elastic collisions. We derive and experimentally verify a theoretical model in terms of impulsive differential equations for the Graham escapement mechanism in a Seth Thomas tower clock. The model offers insight into the clock’s mechanical behavior and the functionality of the deadbeat escapement mechanism. VC 2012 American Association of Physics Teachers. -

Design Principles for Tower and Steeple Restoration

Design Principles for Tower and Steeple Restoration Robert Fulmer Fulmer Associates LLC P.O. Box 434, North Conway, NH 03860 Phone: 603-828-2458 • E-mail: [email protected] S Y M P O S I U M O N B U I L D I N G E N V E L O P E T E C H N O L O G Y • O C T O B E R 2 0 1 6 F U L M E R • 5 7 Abstract The contemporary tectonics of analyzing and designing the restoration or construction of architectural towers and steeples can both inspire and confound contemporary design professionals. The effective design of steeples, bell towers, spires, and clock towers requires a multidisciplinary synthesis of technical, aesthetic, and engineering requirements that are unique to tower architecture. In this presentation, the speaker will discuss construction con siderations and design problems inherent to tower projects by reviewing recent restoration case histories. The information shared will help designers to produce effective and thorough design processes for architectural tower and steeple projects. Speaker Robert Fulmer — Fulmer Associates LLC ROBERT FUlmER specializes in the analysis and diagnosis of building envelope issues for both historical and contemporary structures. He provides inspection, design, specifica tion, and project management services for building envelope projects involving institutional, academic, and ecclesiastical structures. Fulmer is a published author and has lectured on historical preservation and contemporary building envelope topics. He is past president of the New England Chapter of RCi, inc. and currently serves on the board of directors of the National Slate Association and is chair of its Education Committee. -

Mark Elling Rosheim Leonardo's Lost Robots

Mark Elling Rosheim Leonardo’s Lost Robots Mark Elling Rosheim Leonardo’s Lost Robots With 203 Images Author Mark Elling Rosheim President Ross-Hime Designs Inc. 1313 5th Street S.E. Minneapolis, MN 55414 USA web: www.anthrobot.com Library of Congress Control Number: 2005934414 ISBN-10 3-540-28440-0 Springer Berlin Heidelberg New York ISBN-13 978-3-540-28440-6 Springer Berlin Heidelberg New York This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitations, broad- casting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9, 1965, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Violations are liable to prosecution under the German Copyright Law. Springer is a part of Springer Science+Business Media springer.com © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2006 Printed in Germany The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the rel- evant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. Cover design: Erich Kirchner, Heidelberg Typesetting and layout: Büro Stasch · Bayreuth ([email protected]) Production: Almas Schimmel Printing and binding: Stürtz AG, Würzburg Printed on acid-free paper 89/3141/as – 5 4 3 2 1 [… You know what they say.