Abhidharmakosa Study Materials Chapter I: Dhatu (Elements)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

\(Cont'd-020310-Heart Sutra Transcribing\)

The Heart of Perfect Wisdom— Lecture on The Heart of Prajñā Pāramitā Sutra (part 2) Transcribed and edited from a talk given by Ven. Jian-Hu on March 10, 2002 at Buddha Gate Monastery ©2002 Buddha Gate Monastery•For Free Distribution Only Translation of Sanskrit Words When Buddhism came to China about two thousand years ago, the Indian Buddhist masters cooperated with the Chinese masters and set up some rules on translation. They were meticulous about the translation process. One of the rules is that if the word has multiple meanings then it should not be translated because if we translate it one way we lose its other meanings. Another rule is that if the Sanskrit word doesn’t have a corresponding concept in Chinese, then it is not translated. Prajñā, nirvana, and skandha are Sanskrit words. Skandha has multiple meanings. There is no corresponding word to explain prajñā or nirvana either in Chinese, or in English. Does anyone know what nirvana is? Well, some 6th grader knows! Last week when I was invited to an intermediate school to introduce Buddhism, I asked, “What is nirvana?” One child said, “I know, it’s a rock band!” Another child raised his hand and said, “nirvana is ultimate peace.” I was really surprised. That is a really good way to describe nirvana – ultimate peace. The Five Skandhas Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, while deeply immersed in prajñā pāramitā, clearly perceived the empty nature of the five skandhas, and transcended all suffering. Skandha is a Sanskrit word and it means aggregate. Aggregate is an assembly of things. -

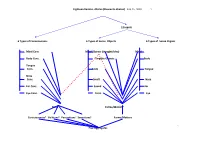

18 Phases Or Realms

Eighteen Realms- dhatus (Elements-dhatus) Feb.16, 2020 1. 12 inputs 6 Types of Consciousness 6 Types of Sense Objects 6 Types of Sense Organs Mind Cons. Mind Objects (thought/idea) Mind Body Cons. Tangible Objects Body Tongue Cons. Taste Tongue Nose Cons. Smell Nose Ear Cons. Sound Ear Eye Cons. Form Eye Mind Forms/Matters1 Consciousness5 Volitions4 Perceptions3 Sensations2 Forms/Matters . Five Aggregates P2. 1. Rupa: Form or (Matter) Aggregate: the Four Great Elements: 1) Solidity, 2) Fluidity, 3) Heat, 4) Wind/Motion which include the five physical sense-organs i.e. the faculties of the eye, ear, nose, tongue, body besides the brain/mind (note: the brain is an organ, not the mind which is an abstract noun). These sense organs are in contact with the external objects of visible form, sound, odor, taste and tangible things and the mind faculty which corresponds to the intangible objects such as thoughts, ideas, and conceptions. 2. Vedana: Sensations- Feelings (generated by the 6 sense organs eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, brain/mind) 3. Samjna: Perception (Conception): The mental function of shape, color, length, pain, pleasure, un-pleasure, neutral. 4. Samskara: Volition-Mental formation: i.e. flashback, will, intention, or the mental function that accounts for craving. 5. Vijnana : Consciousness( Cognition, discrimination-Mano consciousness): the respective consciousness arises when 6 sense organs eye , ear, nose, tongue, body, brain/mind are in contact with the 6 sense objects form , sound, smell, taste, tangible objects , and mental objects. Please be note that Vijnana Consciousness can be further classified into the 6th, 7th and the 8th according to the Vijhanavada (Mere-Mind) School: Mano Consciousness (6th Consciousness): The front 5 senses report to and co-ordinate by the 6th senses in reaction to the 6 sense objects, gather sense data, discriminate, recall it’s the active, coarse and manifest portion of the Manas Vijnanna. -

Lankavatara-Sutra.Pdf

Table of Contents Other works by Red Pine Title Page Preface CHAPTER ONE: - KING RAVANA’S REQUEST CHAPTER TWO: - MAHAMATI’S QUESTIONS I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI XXXII XXXIII XXXIV XXXV XXXVI XXXVII XXXVIII XXXIX XL XLI XLII XLIII XLIV XLV XLVI XLVII XLVIII XLIX L LI LII LIII LIV LV LVI CHAPTER THREE: - MORE QUESTIONS LVII LVII LIX LX LXI LXII LXII LXIV LXV LXVI LXVII LXVIII LXIX LXX LXXI LXXII LXXIII LXXIVIV LXXV LXXVI LXXVII LXXVIII LXXIX CHAPTER FOUR: - FINAL QUESTIONS LXXX LXXXI LXXXII LXXXIII LXXXIV LXXXV LXXXVI LXXXVII LXXXVIII LXXXIX XC LANKAVATARA MANTRA GLOSSARY BIBLIOGRAPHY Copyright Page Other works by Red Pine The Diamond Sutra The Heart Sutra The Platform Sutra In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu Lao-tzu’s Taoteching The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain The Zen Works of Stonehouse: Poems and Talks of a 14th-Century Hermit The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma P’u Ming’s Oxherding Pictures & Verses TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE Zen traces its genesis to one day around 400 B.C. when the Buddha held up a flower and a monk named Kashyapa smiled. From that day on, this simplest yet most profound of teachings was handed down from one generation to the next. At least this is the story that was first recorded a thousand years later, but in China, not in India. Apparently Zen was too simple to be noticed in the land of its origin, where it remained an invisible teaching. -

Buddhist Psychology

CHAPTER 1 Buddhist Psychology Andrew Olendzki THEORY AND PRACTICE ince the subject of Buddhist psychology is largely an artificial construction, Smixing as it does a product of ancient India with a Western movement hardly a century and a half old, it might be helpful to say how these terms are being used here. If we were to take the term psychology literally as referring to “the study of the psyche,” and if “psyche” is understood in its earliest sense of “soul,” then it would seem strange indeed to unite this enterprise with a tradition that is per- haps best known for its challenge to the very notion of a soul. But most dictio- naries offer a parallel definition of psychology, “the science of mind and behavior,” and this is a subject to which Buddhist thought can make a significant contribution. It is, after all, a universal subject, and I think many of the methods employed by the introspective traditions of ancient India for the investigation of mind and behavior would qualify as scientific. So my intention in using the label Buddhist Psychology is to bring some of the insights, observations, and experi- ence from the Buddhist tradition to bear on the human body, mind, emotions, and behavior patterns as we tend to view them today. In doing so we are going to find a fair amount of convergence with modern psychology, but also some intriguing diversity. The Buddhist tradition itself, of course, is vast and has many layers to it. Al- though there are some doctrines that can be considered universal to all Buddhist schools,1 there are such significant shifts in the use of language and in back- ground assumptions that it is usually helpful to speak from one particular per- spective at a time. -

Com 23 Draft B

Community Issue 23 - Page 1 Autumn 2005 / 2548 The Upāsaka & Upāsikā Newsletter Issue No. 23 Dagoba at Mahintale Dagoba InIn thisthis issue.......issue....... InIn peoplepeople wewe trusttrust ?? TheThe Temple at Kosgoda The wisdom of the heartheart SicknessSickness——A Teacher AssistedAssisted DyingDying MakingMaking connectionsconnections beyond words BluebellBluebell WalkWalk Community Community Issue 23 - Page 2 In people we trust? Multiculturalism and community relations have been This is a thoroughly uncomfortable position to be in, as much in the news over recent months. The tragedy of anyone who has suffered from arbitrary discrimination can the London bombings and the spotlight this has attest. There is a feeling of helplessness that whatever one thrown on to what is called ‘the Moslem community’ says or does will be misinterpreted. There is a resentment has led me to reflect upon our own Buddhist that one is being treated unfairly. Actions that would pre- ‘community’. Interestingly, the name of this newslet- viously have been taken at face value are now suspected of ter is ‘Community’, and this was chosen in discussion having a hidden agenda in support of one’s group. In this between a number of us, because it reflected our wish situation, rumour and gossip tend to flourish, and attempts to create a supportive and inclusive network of Forest to adopt a more inclusive position may be regarded with Sangha Buddhist practitioners. suspicion, or misinterpreted to fit the stereotype. The AUA is predominantly supported by western Once a community has polarised, it can take a great deal converts to Buddhism. Some of those who frequent of work to re-establish trust. -

Three Texts on Consciousness Only

THREE TEXTS ON CONSCIOUSNESS ONLY dBET Alpha PDF Version © 2017 All Rights Reserved BDK English Tripit aka 60-1, II, III THREE TEXTS ON CONSCIOUSNESS ONLY Demonstration of Consciousness Only by Hsüan-tsang The Thirty Verses on Consciousness Only by Vasubandhu The Treatise in Twenty Verses on Consciousness Only by Vasubandhu Translated from the Chinese of Hsiian-tsang (Taisho Volume 31, Numbers 1585, 1586, 1590) by Francis H. Cook Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research 1999 © 1999 by Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai and Numata Center for Buddhist Translation Research All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transcribed in any form or by any means —electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise— without the prior written permission of the publisher. First Printing, 1999 ISBN: 1-886439-04-4 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 95-079041 Published by Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research 2620 Warring Street Berkeley, California 94704 Printed in the United States of America A Message on the Publication of the English Tripitaka The Buddhist canon is said to contain eighty-four thousand different teachings. I believe that this is because the Buddha’s basic approach was to prescribe a different treatment for every spiritual ailment, much as a doctor prescribes a different medicine for every medical ailment. Thus his teachings were always appropriate for the particu lar suffering individual and for the time at which the teaching was given, and over the ages not one of his prescriptions has failed to relieve the suffering to which it was addressed. -

Some Reflections on the Place of Philosophy in the Study of Buddhism 145

Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies ^-*/^z ' '.. ' ' ->"•""'",g^ x Volume 18 • Number 2 • Winter 1995 ^ %\ \l '»!#;&' $ ?j On Method \>. :''i.m^--l'-' - -'/ ' x:N'' ••• '; •/ D. SEYFORT RUEGG £>~C~ ~«0 . c/g Some Reflections on the Place of Philosophy in the Study of Buddhism 145 LUIS O. G6MEZ Unspoken Paradigms: Meanderings through the Metaphors of a Field 183 JOSE IGNACIO CABEZ6N Buddhist Studies as a Discipline and the Role of Theory 231 TOM TILLEMANS Remarks on Philology 269 C. W. HUNTINGTON, JR. A Way of Reading 279 JAMIE HUBBARD Upping the Ante: [email protected] 309 D. SEYFORT RUEGG Some Reflections on the Place of Philosophy in the Study of Buddhism I It is surely no exaggeration to say that philosophical thinking constitutes a major component in Buddhism. To say this is of course not to claim that Buddhism is reducible to any single philosophy in some more or less restrictive sense but, rather, to say that what can be meaningfully described as philosophical thinking comprises a major part of its proce dures and intentionality, and also that due attention to this dimension is heuristically necessary in the study of Buddhism. If this proposition were to be regarded as problematic, the difficulty would seem to be due to certain assumptions and prejudgements which it may be worthwhile to consider here. In the first place, even though the philosophical component in Bud dhism has been recognized by many investigators since the inception of Buddhist studies as a modern scholarly discipline more than a century and a half ago, it has to be acknowledged that the main stream of these studies has, nevertheless, quite often paid little attention to the philosoph ical. -

Pain and Flourishing in Mahayana Buddhist Moral Thought

SOPHIA DOI 10.1007/s11841-017-0619-4 A Nirvana that Is Burning in Hell: Pain and Flourishing in Mahayana Buddhist Moral Thought Stephen E. Harris1 # The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract This essay analyzes the provocative image of the bodhisattva, the saint of the Indian Mahayana Buddhist tradition, descending into the hell realms to work for the benefit of its denizens. Inspired in part by recent attempts to naturalize Buddhist ethics, I argue that taking this ‘mythological’ image seriously, as expressing philosophical insights, helps us better understand the shape of Mahayana value theory. In particular, it expresses a controversial philosophical thesis: the claim that no amount of physical pain can disrupt the flourishing of a fully virtuous person. I reconstruct two related elements of early Buddhist psychology that help us understand this Mahayana position: the distinction between hedonic sensation (vedanā) and virtuous or nonvirtous mental states (kuśala/akuśala-dharma); and the claim that humans are massively deluded as to what constitutes well-being. Doing so also lets me emphasize the continuity between early Buddhist and Mahayana traditions in their views on well-being and flourishing. Keywords Mahayana Buddhism . Buddhist ethics . Buddhism . Ethics . Hell Julia Annas has shown that taking seriously Stoic and Epicurean claims that the sage is happy even while being tortured on the rack helps articulate the structure of their ethics, and in particular the relationship between virtue (arête) and happiness (eudaimonia).1 In this essay, I apply this strategy to Mahayana Buddhist moral philosophy by taking seriously the image of the bodhisattva joyfully diving into the hell realms. -

Unit 4 Philosophy of Buddhism

Philosophy of Buddhism UNIT 4 PHILOSOPHY OF BUDDHISM Contents 4.0 Objectives 4.1 Introduction 4.2 The Four Noble Truths 4.3 The Eightfold Path in Buddhism 4.4 The Doctrine of Dependent Origination (Pratitya-samutpada) 4.5 The Doctrine of Momentoriness (Kshanika-vada) 4.6 The Doctrine of Karma 4.7 The Doctrine of Non-soul (anatta) 4.8 Philosophical Schools of Buddhism 4.9 Let Us Sum Up 4.10 Key Words 4.11 Further Readings and References 4.0 OBJECTIVES This unit, the philosophy of Buddhism, introduces the main philosophical notions of Buddhism. It gives a brief and comprehensive view about the central teachings of Lord Buddha and the rich philosophical implications applied on it by his followers. This study may help the students to develop a genuine taste for Buddhism and its philosophy, which would enable them to carry out more researches and study on it. Since Buddhist philosophy gives practical suggestions for a virtuous life, this study will help one to improve the quality of his or her life and the attitude towards his or her life. 4.1 INTRODUCTION Buddhist philosophy and doctrines, based on the teachings of Gautama Buddha, give meaningful insights about reality and human existence. Buddha was primarily an ethical teacher rather than a philosopher. His central concern was to show man the way out of suffering and not one of constructing a philosophical theory. Therefore, Buddha’s teaching lays great emphasis on the practical matters of conduct which lead to liberation. For Buddha, the root cause of suffering is ignorance and in order to eliminate suffering we need to know the nature of existence. -

A Buddhist Inspiration for a Contemporary Psychotherapy

1 A BUDDHIST INSPIRATION FOR A CONTEMPORARY PSYCHOTHERAPY Gay Watson Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the School of Oriental & African Studies, University of London. 1996 ProQuest Number: 10731695 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731695 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT It is almost exactly one hundred years since the popular and not merely academic dissemination of Buddhism in the West began. During this time a dialogue has grown up between Buddhism and the Western discipline of psychotherapy. It is the contention of this work that Buddhist philosophy and praxis have much to offer a contemporary psychotherapy. Firstly, in general, for its long history of the experiential exploration of mind and for the practices of cultivation based thereon, and secondly, more specifically, for the relevance and resonance of specific Buddhist doctrines to contemporary problematics. Thus, this work attempts, on the basis of a three-way conversation between Buddhism, psychotherapy and various themes from contemporary discourse, to suggest a psychotherapy that may be helpful and relevant to the current horizons of thought and contemporary psychopathologies which are substantially different from those prevalent at the time of psychotherapy's early years. -

Explanations of Dukkha 383

Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 21 • Number 2 • 1998 PIERRE ARfcNES Herm6neutique des tantra: 6tude de quelques usages du «sens cach6» 173 GEORGES DREYFUS The Shuk-den Affair: History and Nature of a Quarrel 227 ROBERT MAYER The Figure of MaheSvara/Rudra in the rNin-ma-pa Tantric Tradition 271 JOHN NEWMAN Islam in the Kalacakra Tantra 311 MAX NIHOM Vajravinaya and VajraSaunda: A 'Ghost' Goddess and her Syncretic Spouse 373 TILMANN VETTER Explanations of dukkha 383 Index to JIABS 11-21, by Torn TOMABECHI 389 English summary of the article by P. Arenes 409 TILMANN VETTER Explanations of dukkha The present contribution presents some philological observations and a historical assumption concerning the First Noble Truth. It is well-known to most buddhologists and many Buddhists that the explanations of the First Noble Truth in the First Sermon as found in the Mahavagga of the Vinayapitaka and in some other places conclude with a remark on the five upadanakkhandha, literally: 'branches of appro priation'. This remark is commonly understood as a summary. Practically unknown is the fact that in Hermann OLDENBERG's edition of the Mahavagga1 (= Vin I) this concluding remark contains the parti cle pi, like most of the preceding explanations of dukkha. The preceding explanations are: jati pi dukkha, jara pi dukkha, vyadhi pi dukkha, maranam pi dukkham, appiyehi sampayogo dukkho, piyehi vippayogo dukkho, yam p' iccham na labhati tarn2 pi dukkham (Vin I 10.26). Wherever pi here appears it obviously has the function of coordinating examples of events or processes that cause pain (not: are pain3): birth is causing pain, as well as decay, etc.4 1. -

The Realm of Enlightenment in Vijñaptimātratā: the Formulation Of

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES EDITOR-IN-CHIEF A. K. Narain University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA EDITORS Heinz Bechert Leon Hurvitz Universitdt Gottingen, FRG UBC, Vancouver, Canada Lewis Lancaster Alexander W. MacDonald University of California, Berkeley, USA Universite de Paris X, Nanterre, France B.J. Stavisky Alex Way man WNIIR, Moscow, USSR Columbia University, New York, USA ASSOCIATE EDITOR Stephan Beyer University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA Volume 3 1980 Number 2 CONTENTS I. ARTICLES 1. A Yogacara Analysis of the Mind, Based on the Vijndna Section of Vasubandhu's Pancaskandhaprakarana with Guna- prabha's Commentary, by Brian Galloway 7 2. The Realm of Enlightenment in Vijnaptimdtratd: The Formu lation of the "Four Kinds of Pure Dharmas", by Noriaki Hakamaya, translated from the Japanese by John Keenan 21 3. Hu-Jan Nien-Ch'i (Suddenly a Thought Rose) Chinese Under standing of Mind and Consciousness, by Whalen Lai 42 4. Notes on the Ratnakuta Collection, by K. Priscilla Pedersen 60 5. The Sixteen Aspects of the Four Noble Truths and Their Opposites, by Alex Wayman 67 II. SHORT PAPERS 1. Kaniska's Buddha Coins — The Official Iconography of Sakyamuni & Maitreya, by Joseph Cribb 79 2. "Buddha-Mazda" from Kara-tepe in Old Termez (Uzbekistan): A Preliminary Communication, by Boris J. Stavisky 89 3. FausbpU and the Pali Jatakas, by Elisabeth Strandberg 95 III. BOOK REVIEWS 1. Love and Sympathy in Theravada Buddhism, by Harvey B. Aronson 103 2. Chukan to Vuishiki (Madhyamika and Vijriaptimatrata), by Gadjin Nagao 105 3. Introduction a la connaissance des hlvin bal de Thailande, by Anatole-Roger Peltier 107 4.