HSHAZ) for Housing and Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Walls but on the Rampart Underneath and the Ditch Surrounding Them

A walk through 1,900 years of history The Bar Walls of York are the finest and most complete of any town in England. There are five main “bars” (big gateways), one postern (a small gateway) one Victorian gateway, and 45 towers. At two miles (3.4 kilometres), they are also the longest town walls in the country. Allow two hours to walk around the entire circuit. In medieval times the defence of the city relied not just on the walls but on the rampart underneath and the ditch surrounding them. The ditch, which has been filled in almost everywhere, was once 60 feet (18.3m) wide and 10 feet (3m) deep! The Walls are generally 13 feet (4m) high and 6 feet (1.8m) wide. The rampart on which they stand is up to 30 feet high (9m) and 100 feet (30m) wide and conceals the earlier defences built by Romans, Vikings and Normans. The Roman defences The Normans In AD71 the Roman 9th Legion arrived at the strategic spot where It took William The Conqueror two years to move north after his the rivers Ouse and Foss met. They quickly set about building a victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. In 1068 anti-Norman sound set of defences, as the local tribe –the Brigantes – were not sentiment in the north was gathering steam around York. very friendly. However, when William marched north to quell the potential for rebellion his advance caused such alarm that he entered the city The first defences were simple: a ditch, an embankment made of unopposed. -

Lancaster-Cultural-Heritage-Strategy

Page 12 LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY REPORT FOR LANCASTER CITY COUNCIL Page 13 BLUE SAIL LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY MARCH 2011 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................3 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................7 2 THE CONTEXT ................................................................................10 3 RECENT VISIONING OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE 24 4 HOW LANCASTER COMPARES AS A HERITAGE CITY...............28 5 LANCASTER DISTRICT’S BUILT FABRIC .....................................32 6 LANCASTER DISTRICT’S CULTURAL HERITAGE ATTRACTIONS39 7 THE MANAGEMENT OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE 48 8 THE MARKETING OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE.....51 9 CONCLUSIONS: SWOT ANALYSIS................................................59 10 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES FOR LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE .......................................................................................65 11 INVESTMENT OPTIONS..................................................................67 12 OUR APPROACH TO ASSESSING ECONOMIC IMPACT ..............82 13 TEN YEAR INVESTMENT FRAMEWORK .......................................88 14 ACTION PLAN ...............................................................................107 APPENDICES .......................................................................................108 2 Page 14 BLUE SAIL LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY MARCH 2011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Lancaster is widely recognised -

Appendix 5 Fylde

FYLDE DISTRICT - APPENDIX 5 SUBSIDISED LOCAL BUS SERVICE EVENING AND SUNDAY JOURNEYS PROPOSED TO BE WITHDRAWN FROM 18 MAY 2014 LANCASTER - GARSTANG - POULTON - BLACKPOOL 42 via Galgate - Great Eccleston MONDAY TO SATURDAY Service Number 42 42 42 $ $ $ LANCASTER Bus Station 1900 2015 2130 SCOTFORTH Boot and Shoe 1909 2024 2139 LANCASTER University Gates 1912 2027 2142 GALGATE Crossroads 1915 2030 2145 CABUS Hamilton Arms 1921 2036 2151 GARSTANG Bridge Street 1926 2041 2156 CHURCHTOWN Horns Inn 1935 2050 2205 ST MICHAELS Grapes Hotel 1939 2054 2209 GREAT ECCLESTON Square 1943 2058 2213 POULTON St Chads Church 1953 2108 2223 BLACKPOOL Layton Square 1958 2113 2228 BLACKPOOL Abingdon Street 2010 2125 2240 $ - Operated on behalf of Lancashire County Council BLACKPOOL - POULTON - GARSTANG - LANCASTER 42 via Great Eccleston - Galgate MONDAY TO SATURDAY Service Number 42 42 42 $ $ $ BLACKPOOL Abingdon Street 2015 2130 2245 BLACKPOOL Layton Square 2020 2135 2250 POULTON Teanlowe Centre 2032 2147 2302 GREAT ECCLESTON Square 2042 2157 2312 ST MICHAELS Grapes Hotel 2047 2202 2317 CHURCHTOWN Horns Inn 2051 2206 2321 GARSTANG Park Hill Road 2059 2214 2329 CABUS Hamilton Arms 2106 2221 2336 GALGATE Crossroads 2112 2227 2342 LANCASTER University Gates 2115 2230 2345 SCOTFORTH Boot and Shoe 2118 2233 2348 LANCASTER Bus Station 2127 2242 2357 $ - Operated on behalf of Lancashire County Council LIST OF ALTERNATIVE TRANSPORT SERVICES AVAILABLE – Stagecoach in Lancaster Service 2 between Lancaster and University Stagecoach in Lancaster Service 40 between Lancaster and Garstang (limited) Blackpool Transport Service 2 between Poulton and Blackpool FYLDE DISTRICT - APPENDIX 5 SUBSIDISED LOCAL BUS SERVICE EVENING AND SUNDAY JOURNEYS PROPOSED TO BE WITHDRAWN FROM 18 MAY 2014 PRESTON - LYTHAM - ST. -

CYCLING for ALL CONTENTS Route 1: the Lune Valley

LANCASTER, MORECAMBE & THE LUNE VALLEY IN OUR CITY, COAST & COUNTRYSIDE CYCLING FOR ALL CONTENTS Route 1: The Lune Valley..................................................................................4 Route 2: The Lune Estuary ..............................................................................6 Route 3: Tidal Trails ..........................................................................................8 Route 4: Journey to the Sea............................................................................10 Route 5: Brief Encounters by Bike..................................................................11 Route 6: Halton and the Bay ..........................................................................12 Cycling Online ................................................................................................14 2 WELCOME TO CYCLING FOR ALL The District is rightly proud of its extensive cycling network - the largest in Lancashire! We're equally proud that so many people - local and visitors alike - enjoy using the whole range of routes through our wonderful city, coast and countryside. Lancaster is one of just six places in the country to be named a 'cycling demonstration' town and we hope this will encourage even more of us to get on our bikes and enjoy all the benefits cycling brings. To make it even easier for people to cycle Lancaster City Council has produced this helpful guide, providing at-a-glance information about six great rides for you, your friends and family to enjoy. Whether you've never ridden -

Lancaster Archaeological and Historical Society Research Group Newsletter

Lancaster Archaeological and Multum in parvo Historical Society http://lahs.archaeologyuk.org/ Research Group Newsletter orem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipisci No. 2: August 2020 Welcome to the Research Group e-newsletter We received encouraging feedback from Society amount of research now being conducted online, members following the first issue of the e-newsletter news that the National Archives are allowing people in May 2020 which was much appreciated. The e- to download their digital resources free during the newsletter is open to all Society members and guest pandemic has been very welcome. If you have a authors should they be interested in publishing a brief Lancashire County Library ticket it is possible to letter, or a short article of 500-750 words on an access information online such as the Oxford archaeological or historical subject related to Dictionary of National Biography and several local Lancaster and surrounding areas. Longer articles are papers from the nineteenth century (with thanks to Dr published in Contrebis Michael Winstanley). As lockdown restrictions begin to ease, do not delay in taking advantage when The last five months have been a difficult time for research facilities re-open because with social researchers with the Covid-19 lockdown making distancing measures still in force, there are likely to face-to-face meetings impossible; archive, museum be appointment systems or time-limited visits and library services closed, and employees in many introduced. organisations working from home. Research can be a lonely occupation at the best of times so the surge in If you would like to join the Research Group or online virtual meetings has offered some welcome contribute to the e-newsletter, contact details are relief from social isolation. -

Lancaster Castle: the Rebuilding of the County Gaol and Courts

Contrebis 2019 v37 LANCASTER CASTLE: THE REBUILDING OF THE COUNTY GAOL AND COURTS John Champness Abstract This paper details the building and rebuilding of Lancaster Castle in the late-eighteenth and early- nineteenth centuries to expand and improve the prison facilities there. Most of the present buildings in the Castle date from a major scheme of extending the County Gaol, undertaken in the last years of the eighteenth century. The principal architect was Thomas Harrison, who had come to Lancaster in 1782 after winning the competition to design Skerton Bridge (Champness 2005, 16). The scheme arose from concern about the unsatisfactory state of the Gaol which was largely unchanged from the medieval Castle (Figure 1). Figure 1. Plan of Lancaster Castle taken from Mackreth’s map of Lancaster, 1778 People had good reasons for their concern, because life in Georgian gaols was somewhat disorganised. The major reason lay in how the role of gaols had been expanded over the years in response to changing pressures. County gaols had originally been established in the Middle Ages to provide short-term accommodation for only two groups of people – those awaiting trial at the twice- yearly Assizes, and convicted criminals who were waiting for their sentences to be carried out, by hanging or transportation to an overseas colony. From the late-seventeenth century, these people were joined by debtors. These were men and women with cash-flow problems, who could avoid formal bankruptcy by forfeiting their freedom until their finances improved. During the mid- eighteenth century, numbers were further increased by the imprisonment of ‘felons’, that is, convicted criminals who had not been sentenced to death, but could not be punished in a local prison or transported. -

2005 No. 170 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2005 No. 170 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The County of Lancashire (Electoral Changes) Order 2005 Made - - - - 1st February 2005 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Whereas the Boundary Committee for England(a), acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(b), has submitted to the Electoral Commission(c) recommendations dated October 2004 on its review of the county of Lancashire: And whereas the Electoral Commission have decided to give effect, with modifications, to those recommendations: And whereas a period of not less than six weeks has expired since the receipt of those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Electoral Commission, in exercise of the powers conferred on them by sections 17(d) and 26(e) of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling them in that behalf, hereby make the following Order: Citation and commencement 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the County of Lancashire (Electoral Changes) Order 2005. (2) This Order shall come into force – (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2005, on the day after that on which it is made; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2005. Interpretation 2. In this Order – (a) The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of the Electoral Commission, established by the Electoral Commission in accordance with section 14 of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 (c.41). The Local Government Commission for England (Transfer of Functions) Order 2001 (S.I. -

The Height of Its Womanhood': Women and Genderin Welsh Nationalism, 1847-1945

'The height of its womanhood': Women and genderin Welsh nationalism, 1847-1945 Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Kreider, Jodie Alysa Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 04:59:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280621 'THE HEIGHT OF ITS WOMANHOOD': WOMEN AND GENDER IN WELSH NATIONALISM, 1847-1945 by Jodie Alysa Kreider Copyright © Jodie Alysa Kreider 2004 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partia' Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2004 UMI Number: 3145085 Copyright 2004 by Kreider, Jodie Alysa All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3145085 Copyright 2004 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. -

St. Paul's Church, Scotforth

St. Paul’s Church, Scotforth Contents Summary 2 Our Vision 3 Who Is God Calling? 3 The Parish and Wider Community 4 Church Organization 7 The Church Community 8 Together we are stronger 10 Our Buildings 11 The Church 12 The Hala Centre 13 The Parish Hall 14 The Vicarage 15 The Church Finances 16 Our Schools 17 Our Links into the Wider Community 20 1 Summary St Paul’s Church Scotforth is a vibrant and accepting community in Lancaster. The church building is a landmark on the A6 south of the city centre, and the vicarage is adjacent in its own private grounds. Living here has many attractive features. We have our own outstanding C of E primary school nearby with which we have strong links. And very close to the parish we also find outstanding secondary schools, Ripley C of E academy and two top-rated grammar schools. In addition Lancaster’s two universities bring lively people and facilities to the area. Traveling to and from Scotforth has many possibilities. We rapidly connect to the M6 and to the west coast main train line. Our proximity to beautiful countryside keeps many residents happy to remain. We are close to the Lake District, the Yorkshire Dales, Bowland forest, Morecambe Bay, to mention just a few such attractions. Our Church is a welcoming and friendly place. Our central churchmanship is consistent with the lack of a central aisle in our unusual “pot” church building! Our regular services (BCP or traditional, in church or in the Hala Centre) use the Bible lectionary to encourage understanding and action, but we also are keen to develop innovative forms of worship. -

Revised Draft Experiences with Inter Basin Water

REVISED DRAFT EXPERIENCES WITH INTER BASIN WATER TRANSFERS FOR IRRIGATION, DRAINAGE AND FLOOD MANAGEMENT ICID TASK FORCE ON INTER BASIN WATER TRANSFERS Edited by Jancy Vijayan and Bart Schultz August 2007 International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage (ICID) 48 Nyaya Marg, Chanakyapuri New Delhi 110 021 INDIA Tel: (91-11) 26116837; 26115679; 24679532; Fax: (91-11) 26115962 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.icid.org 1 Foreword FOREWORD Inter Basin Water Transfers (IBWT) are in operation at a quite substantial scale, especially in several developed and emerging countries. In these countries and to a certain extent in some least developed countries there is a substantial interest to develop new IBWTs. IBWTs are being applied or developed not only for irrigated agriculture and hydropower, but also for municipal and industrial water supply, flood management, flow augmentation (increasing flow within a certain river reach or canal for a certain purpose), and in a few cases for navigation, mining, recreation, drainage, wildlife, pollution control, log transport, or estuary improvement. Debates on the pros and cons of such transfers are on going at National and International level. New ideas and concepts on the viabilities and constraints of IBWTs are being presented and deliberated in various fora. In light of this the Central Office of the International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage (ICID) has attempted a compilation covering the existing and proposed IBWT schemes all over the world, to the extent of data availability. The first version of the compilation was presented on the occasion of the 54th International Executive Council Meeting of ICID in Montpellier, France, 14 - 19 September 2003. -

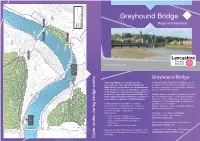

Greyhound Bridge for Buses Or Cycle S No Right Turn

y FS High School 10.7m Fleming House y N Stewart 97 to 107 Court masonr g in p Skerton Tide Gauge lo Learning S Centre 1 to h PH 3 t OWEN ROAD Pa Lune Park Rigg House Childrens Centre Mast (Telecommunication) Y MAINWA Mud 1 Acre Court 11.0m to Path o 91 10.7m t 3 AR Centre 65 Ellershaw House 5 ath e Ryelands cle P RYELANDS PARK ingl Cy 1 347050 347100 16 347150 347200 347250 347300 347350 347400 347450 347500 347550 347600 347650 347700 347750 347800 347850 347900 347950 348000 348050 348100 Dr a 462600N 348150E 1 in E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E ST LUKE'S to and Sh 3 Mud CHURCH Greg House 6 Bandstand 63 L AD 4 IES 1 53 to W Miller 12 St Luke's Court 12.5m Church 33 1 to 3 Frankland House 15 Park Church Court 462550N rise Garage 11.9m p 41 to 51 r 7.3m 22 e ake Ente 1 L Shards Court to FATHERS HOUSE 11 39 Bridg d Shingl 12 e Hou e ELIM CHURCH 13 to se Mud an 23 d Shingl RS 27 ST Mud an 14 462500N Kiln 10.1m Court to 11 7.3m 1 MORECAMBE ROAD n Drai D OA R E REVISEDRevised JUNCTION junction 6.7m e CATON 462450N hingl S NCN 69 footway/ Car Park NCN 69 FOOTWAY / ud and cycleway open at Mud M CYCLEWAY OPEN AT RIVERWAY all times HOUSE Carlisle ALL TIMES e Bridge MORECAMBE ROAD ingl Co Const, ED & Ward Underpass y CCLW Mud and Sh Bdy OUR LADY'S cle Wa Cy 462400N CARLISLE BRIDG CARLISLE CATHOLIC COLLEGE Sewage Pumping SKERTON BRIDG r e Station t 7.9m Rock and Mud 7.6m Wa h g 201 to 207 an Hi 301 to 313 Me 401 to 420 501 to 520 Y North A 601 to 620 View Me SW 701 to 720 G a n High N KI The Old Bus Depot Wate 29 E 93 6.4m ST GEOR -

Your District Council Matters Issue 37

Your District Council Matters Lancaster City Council’s Community Magazine Issue 37 • Spring/Summer 2020 How we’re tackling the Inside climate emergency People’s Jury tackles climate change Flood protection scheme gets underway Plastic fantastic – help us to recycle even more Taking to the streets to help the homeless @lancastercc facebook.com/lancastercc lancaster.gov.uk 2 | Your District Council Matters Spring/Summer 2020 E O M W E L C from Councillor Dr Erica Lewis, leader of Lancaster City Council I’m Erica, and since last May I’ve been the new leader of the city council. I will have met some of you while I’ve been out knocking doors across the district, but thought I’d take this opportunity to introduce myself to everyone else. For more than two decades, I’ve worked I’m passionate about mobilising the skills, and volunteered as a director and trustee talents and wisdom of everyone. So it in the charitable sector, through which is important to me that as a council, we I developed a deep understanding of make sure we’re better connected to every good governance and sound financial neighbourhood across the district. management. We’re looking for ways to build new I’ve also been a Lancashire County partnerships and collaborations to tackle Councillor since 2017; work which big challenges like the climate emergency requires attention to detail (and a bit of a and revitalising our high streets. fascination with sorting out potholes and We all want our district to be a great place blocked drains!).