Starlight Drive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Ball! One of the Most Recognizable Stars on the U.S

TVhome The Daily Home June 7 - 13, 2015 On the Ball! One of the most recognizable stars on the U.S. Women’s World Cup roster, Hope Solo tends the goal as the U.S. 000208858R1 Women’s National Team takes on Sweden in the “2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup,” airing Friday at 7 p.m. on FOX. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., June 7, 2015 — Sat., June 13, 2015 DISH AT&T CABLE DIRECTV CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA SPORTS BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING 5 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 Championship Super Regionals: Drag Racing Site 7, Game 2 (Live) WCIQ 7 10 4 WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Monday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 8 p.m. ESPN2 Toyota NHRA Sum- 12 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 mernationals from Old Bridge Championship Super Regionals Township Race. -

The Novel and Corporeality in the New Media Ecology

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2017 "You Will Hold This Book in Your Hands": The Novel and Corporeality in the New Media Ecology Jason Shrontz University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Shrontz, Jason, ""You Will Hold This Book in Your Hands": The Novel and Corporeality in the New Media Ecology" (2017). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 558. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/558 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “YOU WILL HOLD THIS BOOK IN YOUR HANDS”: THE NOVEL AND CORPOREALITY IN THE NEW MEDIA ECOLOGY BY JASON SHRONTZ A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2017 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF JASON SHRONTZ APPROVED: Dissertation Committee: Major Professor Naomi Mandel Jeremiah Dyehouse Ian Reyes Nasser H. Zawia DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2017 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the relationship between the print novel and new media. It argues that this relationship is productive; that is, it locates the novel and new media within a tense, but symbiotic relationship. This requires an understanding of media relations that is ecological, rather than competitive. More precise, this dissertation investigates ways that the novel incorporates new media. The word “incorporate” refers both to embodiment and physical union. -

Detective Special Agent = DET. =SA Assistant

Detective = DET. Special Agent =SA Assistant Prosecuting Attorney =APA Unknown Male One= UM1 Unknown Male Two- UM2 Unknown Female= UF Tommy Sotomayor= SOTOMAYOR Ul =Unintelligible DET. Today is Thursday, November 6, 2014 and the time is 12:10 p.m. This is Detective with the St. Louis County Police Department's Bureau of Crimes Against Persons, . I'm here in a conference room, in the Saint Louis County Prosecuting Attorney's Office, with a, Special Agent, Special Agent of the F.B.I., and also present in the room is ... Sir, would you say your name for the recorder please? DET. Okay, and it's is that correct? That's correct. DET. Okay ... and what is your date of birth, ? DET. ...and your home address? DET. And do you work at all? DET. Do not. DET. Okay ... and what is your cell phone? What is my what now? DET. Cell phone? Number? DET. Yes Sir. DET. Okay and, a, did you say an apartment number with that? DET okay. mm hmm. DET. So ... you came down here, a, to the Prosecuting Attorney's Office, because you received a Grand Jury Subpoena, is that correct? That is correct. DET Okay and you received that Grand Jury Subpoena a few days ago? Yes. DET. Okay ... and since then, you had a conversation with a, at least one of the Prosecutors here, explaining to you that they would like you to come down to the office today, is that correct? Yes. DET. Okay, uhh ... having said that, a, I think your attendance at the Grand Jury will be later on this afternoon, or, or in a little bit here. -

The Career of John Jacob Niles: a Study in the Intersection of Elite, Traditional, and Popular Musical Performance

The Kentucky Review Volume 12 Article 2 Number 1 Double Issue of v. 12, no. 1/2 Fall 1993 The aC reer of John Jacob Niles: A Study in the Intersection of Elite, Traditional, and Popular Musical Performance Ron Pen University of Kentucky, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review Part of the Music Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Pen, Ron (1993) "The aC reer of John Jacob Niles: A Study in the Intersection of Elite, Traditional, and Popular Musical Performance," The Kentucky Review: Vol. 12 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review/vol12/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kentucky Review by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Career of John Jacob Niles: a Study in the Intersection of Elite, Traditional, and Popular Musical Performance Ron Pen As a young and naive doctoral student, I approached my folklore professor with a dissertation proposal. Quivering with trepidation, I informed him that I intended to provide an initial biography and works of the composer and balladeer John Jacob Niles. The folklorist cast a bemused glance over his tortoise shell glasses and said: "He was a fraud. You realize, of course, that no folklorist would write his obituary." Years later, with the dissertation nestled securely on the library shelves, I recalled this conversation and attempted to reconcile my understanding of John Jacob Niles's career with the folklorist's accusation. -

Snow Patrol, Hands Open It's Hard to Argue When You Won't Stop Making Sense but My Tongue Still Misbehaves and It Keeps Digging My Own Grave with My

Snow Patrol, Hands Open It's hard to argue when you won't stop making sense But my tongue still misbehaves and it keeps digging my own grave with my Hands open, and my eyes open I just keep hoping That your heart opens Why would I sabotage the best thing that I have Well, it makes it easier to know exactly what I want with my... Hands open and my eyes open I just keep hoping that your heart opens It's not as easy as willing it all to be right Gotta be more than hoping it's right I wanna hear you laugh like you really mean it Collapse into me, tired with joy It's not as easy as willing it all to be right Gotta be more than hoping it's right I wanna hear you laugh like you really mean it Collapse into me, tired with joy Put Sufjan Stevens on and we'll play your favorite song "Chicago" bursts to life and your sweet smile remembers you, my Hands open, and my eyes open I just keep hoping That your heart opens It's not as easy as willing it all to be right Gotta be more than hoping it's right I wanna hear you laugh like you really mean it Collapse into me, tired with joy It's not as easy as willing it all to be right Gotta be more than hoping it's right I wanna hear you laugh like you really mean it Collapse into me, tired with joy It's not as easy as willing it all to be right Gotta be more than hoping it's right I wanna hear you laugh like you really mean it Collapse into me, tired with joy Snow Patrol - Hands Open w Teksciory.pl. -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand marking: or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

In the August 2019 Kiwan

AUGUST 2019 ® A TEXAS KEY CLUB CONSTRUCTS A WATER STATION SERVING THE CHILDREN OF WORLD FOR GUATEMALAN SCHOOLCHILDREN CLEAN HANDS OPEN HEARTS FAMILY AFFAIR: GENEALOGY GOES HIGH-TECH MAKER SPACE: CLASSROOM PROMOTES INVENTION MAGIC IN DISNEY: KIWANIS CONVENTION HIGHLIGHTS p001_KIM_0819_Cover.indd 1 + 7/2/19 7:43 AM Play never told me you can’t or don’t or you shouldn’t or you won’t. Play never said be careful! You’re not strong enough. You’re not big enough. You’re not brave enough. Play has always been an invitation. A celebration. A joyous manifestation. Of the cans and wills and what ifs and why nots. Play isn’t one thing. It’s everything. Anything. Play doesn’t care what a body can or cannot do. Because play lives inside us. All of us. Play begs of us: Learn together. Grow together. Be together. Know together. And as we grow older. As the world comes at us with you can’t or don’t or you shouldn’t or you won’t. We come back to what we know. That imagination will never fail us. That words will never hurt us. That play will always shape us. To see the new We-Go-Round™, visit playlsi.com/we-go-round. Landscape Structures has been a proud Vision Partner of ©2019 Landscape Structures Inc. All rights reserved. Kiwanis International since 2013 p002-003_KIM_0819_TOC.indd 2 7/2/19 7:44 AM KIWANIS INTERNATIONAL INSIDE Kiwanis is a global organization of volunteers dedicated to improving the world one child and one community at a time. -

Hello, Hatchlings Families! a Few Reminders

SESSION 3 LCCOOM EEL MEE WW Hello, Hatchlings Families! A few reminders Unexpected Calm down Respect is expected without the crowd baby’s rest Hands on Stay Engaged; exploration Silence phones Let’s go around and introduce ourselves! 1 Smile, talk, sing, share books and play with your baby. Early speech and language skills are associated with success in developing reading, writing, and social skills, in childhood and later in life. Talk, Sing, Share Books & Play. Can You Clap With Two Hands? “Mirror” the faces your baby makes, clap when your RHYME baby claps. Old Mother Goose when she wanted to wander, would fly through the air on a very fine gander. 2 There are many ways to read a story... k about wh up sto al at ke ri T you see. a es M . Once Upon a 1 3 Time 2 4 C ou t’s nt wha . in s the picture And even sing to any tune you like or make up a song! There are Bubbles in the Air Try chanting! “You can do it!” Babies’ brains learn best when you talk directly to them, not by listening to the television. Books Away 3 Name the parts of your baby’s face and talk about the faces they’re making. Who’s That Tapping on my Shoulder & Two Little Eyes to Look Around Two little eyes to look around, Two little ears to hear a sound. One little nose to smell what’s sweet... (take a deep smell) And one little mouth that likes to eat! (mmmmmmm) Use words to describe how you think your baby is feeling. -

Sunday Morning Grid 4/16/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

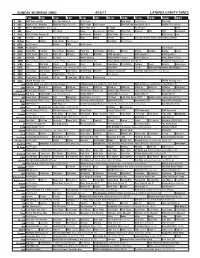

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/16/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Raw Travel Paid Program PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A.: Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Program Red Bull Signature Series (N) Å Hockey: Wild at Blues 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program News 7 ABC News This Week News Sea Rescue Wildlife Rock-Park Outback TBA NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Weird DIY Sci Paid The 32nd Annual Stellar Gospel Music Awards 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Cooking Baking Sara’s 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch White Collar Å White Collar On Guard. White Collar Å White Collar Deadline. 34 KMEX Misa de Pascua Papa Francisco desde El Vaticano. Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio de Baréin. -

English 9.Pdf

English 9 Summer Reading Short Story Selections Please read the following stories carefully. While you read and/or after you read, take notes on: ● key characters ● important conflicts ● settings ● vocabulary that is new to you After reading each story, you should be able to: ● recall the title and author of each story ● summarize each story ● determine the lesson about life offered by each story All stories are included in this PDF; below are links to the individual stories: "Sucker" by Carson McCullers (1963) …………………………………………………..page 2 "Growing Up" by Gary Soto (1990) ……………………………………………………...page 10 "All Summer in a Day" by Ray Bradbury (1954) ……………………………………….page 17 "The War of the Wall" by Toni Cade Bambara (1980) ………………………………….page 23 "Montreal, 1962" by Shauna Singh Baldwin (2012) ……………………………………..page 29 "The Leap" by Louise Erdrich (2009) …………………………………………………….page 32 "Nobody Listens When I Talk" by Annette Sanford (2000) …………………………….page 38 "The Birds" by Daphne du Maurier (1952) ……………………………………………...page 40 1 “Sucker” by Carson McCullers It was always like I had a room to myself. Sucker slept in my bed with me but that didn’t interfere with anything. The room was mine and I used it as I wanted to. Once I remember sawing a trap door in the floor. Last year when I was a sophomore in high school I tacked on my wall some pictures of girls from magazines and one of them was just in her underwear. My mother never bothered me because she had the younger kids to look after. And Sucker thought anything I did was always swell. Whenever I would bring any of my friends back to my room all I had to do was just glance once at Sucker and he would get up from whatever he was busy with and maybe half smile at me, and leave without saying a word. -

Parade Marshal Phil Ford Wows Crowd at Strawberry Festival

•WHS teams capture Three Riv- ers Conference baseball, softball tournament titles. •East’s Palacios, Borja gain state 1A tournament berth. •Lady Gators turn back SCHS in TRC Tournament semis. Sports See page 2-B. ThePublished News since 1890 every Monday and Thursday Reporterfor the County of Columbus and her people. Monday, May 9, 2016 State park sets Volume 125, Number 90 birthday bash Whiteville, North Carolina By JEFFERSON WEAVER 75 Cents Staff Writer Lake Waccamaw State Park is hosting a birthday party. Inside As part of the ongoing centennial celebra- tion of the State Parks System, Superinten- 4-A dent Toby Hall said Lake Waccamaw will host an all-day “and into the evening” music •Several pleas taken festival May 14 from 10 a.m. until 10 p.m. in Superior Court. “This is going to be one of the biggest events of its kind we’ve ever had,” Hall said, “and we want everyone to show up. We have a DIDYOB? lot of out-of-town visitors as well as our faith- ful locals, but we want everyone who might Did you observe ... have been thinking about visiting the park to come out and see what we have to offer.” Joseph Hackney Hall said four local bands will provide Deans, grandson entertainment during the entire event. Gene Wayman and the Depot Jammers will start of Bob Deans, and the day, followed by Southern Just Us, Jimmy Camille Louise Ann Gatlin and Ronnie Fisher with the Backroads Brown, granddaugh- Band. “We’re going to have a little something for ter of Bob High, Strawberry Festival Grand Marshal Phil Ford, left, was driven in the parade by Whiteville attorney Bill Gore.