GET REAL HONORS THESIS Presented to the Honors College of Texas State Univers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Childrens CDG Catalogue

Michael Row The Boat Ashore Deep & Wide Let's Get Crazy - Hannah Montana Muffin Man Standin' In The Need Of Prayer Do Your Own Thing - Cheetah Girls Childrens My Bonnie Lies Over The Ocean Amazing Grace This Is Me - Camp Rock Oh Dear What Can The Matter Be Old Time Religion DIS 3527 Disney Mania 2 Oh Susanna Down In My Heart Songs A Dream Is A Wish Yr Heart Makes - K.Lock Old Macdonald CB40497 Childrns Bible Favs 4 A Whole New World - Lmnt On Top Of Old Smoky Note: All CCB & CB discs are available as a Oh, How I Love Jesus Beauty & The Beast - Jump5 On Top Of Spaghetti CDG disc or a DVD disc or mp3g disc/stick Down By The Riverside Colors Of The Wind - Christy Carlsn Romano One Potato What A Mighty God We Serve Proud Of Your Body - Clay Aiken Pat A Cake Pat A Cake Capital Chartbuster $25 I'm Gonna Sing Strangers Like Me - Everlife CCB2018/25 The Best Of CCB649/25 Childrens Songs 3 I've Got Peace Like A River The Tiki, Tiki, Tiki Room - Hilary Duff Polly Put The Kettle On Whisper A Prayer Under The Sea – Symone Childrens Songs Polly Wolly Doodle DIS FAVS B I N G O Pop Goes The Weasel Disney - $25 Let It Go - Frozen Baa Baa Black Sheep Put Your Finger On Your Nose 8 karaoke tracks & 8 vocal I See the Light - Tangled Can We Fix It (Bob the Builder) Ring Around The Rosey Disney Tracks are usually from Circle Of Life - Lion King Ding Dong Bell Rock A Bye Baby original backings Part Of Your World - The Little Mermaid Girls & Boys Come Out To Play Roll Over A Whole New World - Aladdin Heads & Shoulders Knees & Toes Row Row Your Boat DIS 3247 -

3/30/2021 Tagscanner Extended Playlist File:///E:/Dropbox/Music For

3/30/2021 TagScanner Extended PlayList Total tracks number: 2175 Total tracks length: 132:57:20 Total tracks size: 17.4 GB # Artist Title Length 01 *NSync Bye Bye Bye 03:17 02 *NSync Girlfriend (Album Version) 04:13 03 *NSync It's Gonna Be Me 03:10 04 1 Giant Leap My Culture 03:36 05 2 Play Feat. Raghav & Jucxi So Confused 03:35 06 2 Play Feat. Raghav & Naila Boss It Can't Be Right 03:26 07 2Pac Feat. Elton John Ghetto Gospel 03:55 08 3 Doors Down Be Like That 04:24 09 3 Doors Down Here Without You 03:54 10 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 03:53 11 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 03:52 12 3 Doors Down When Im Gone 04:13 13 3 Of A Kind Baby Cakes 02:32 14 3lw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 04:19 15 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 03:12 16 4 Strings (Take Me Away) Into The Night 03:08 17 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot 03:12 18 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 03:21 19 50 Cent Disco Inferno 03:33 20 50 Cent In Da Club 03:42 21 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 03:57 22 50 Cent P.I.M.P. 04:15 23 50 Cent Wanksta 03:37 24 50 Cent Feat. Nate Dogg 21 Questions 03:41 25 50 Cent Ft Olivia Candy Shop 03:26 26 98 Degrees Give Me Just One Night 03:29 27 112 It's Over Now 04:22 28 112 Peaches & Cream 03:12 29 220 KID, Gracey Don’t Need Love 03:14 A R Rahman & The Pussycat Dolls Feat. -

November 2, 2019 Julien's Auctions: Property From

JULIEN’S AUCTIONS: PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: JULIEN’S AUCTIONS: PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN Four-Time Grammy Award-Winning Pop Diva and Hollywood Superstar’s Iconic “Grease” Leather Jacket and Pants, “Physical” and “Xanadu” Wardrobe Pieces, Gowns, Awards and More to Rock the Auction Stage Portion of the Auction Proceeds to Benefit the Olivia Newton-John Cancer Wellness & Research Centre https://www.onjcancercentre.org NOVEMBER 2, 2019 Los Angeles, California – (June 18, 2019) – Julien’s Auctions, the world-record breaking auction house, honors one of the most celebrated and beloved pop culture icons of all time with their PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN (OBE, AC, HONORARY DOCTORATE OF LETTERS (LA TROBE UNIVERSITY)) auction event live at The Standard Oil Building in Beverly Hills and online at juliensauctions.com. Over 500 of the most iconic film and television worn costumes, ensembles, gowns, personal items and accessories owned and used by the four-time Grammy award-winning singer/Hollywood film star and one of the best-selling musical artists of all time who has sold 100 million records worldwide, will take the auction stage headlining Julien’s Auctions’ ICONS & IDOLS two-day music extravaganza taking place Friday, November 1st and Saturday, November 2nd, 2019. PAGE 1 Julien’s Auctions | 8630 Hayden Place, Culver City, California 90232 | Phone: 310-836-1818 | Fax: 310-836-1818 © 2003-2019 Julien’s Auctions JULIEN’S AUCTIONS: PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN PRESS RELEASE The Cambridge, England born and Melbourne, Australia raised singer and actress began her music career at the age of 14, when she formed an all-girl group, Sol Four, with her friends. -

80S 697 Songs, 2 Days, 3.53 GB

80s 697 songs, 2 days, 3.53 GB Name Artist Album Year Take on Me a-ha Hunting High and Low 1985 A Woman's Got the Power A's A Woman's Got the Power 1981 The Look of Love (Part One) ABC The Lexicon of Love 1982 Poison Arrow ABC The Lexicon of Love 1982 Hells Bells AC/DC Back in Black 1980 Back in Black AC/DC Back in Black 1980 You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC Back in Black 1980 For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) AC/DC For Those About to Rock We Salute You 1981 Balls to the Wall Accept Balls to the Wall 1983 Antmusic Adam & The Ants Kings of the Wild Frontier 1980 Goody Two Shoes Adam Ant Friend or Foe 1982 Angel Aerosmith Permanent Vacation 1987 Rag Doll Aerosmith Permanent Vacation 1987 Dude (Looks Like a Lady) Aerosmith Permanent Vacation 1987 Love In An Elevator Aerosmith Pump 1989 Janie's Got A Gun Aerosmith Pump 1989 The Other Side Aerosmith Pump 1989 What It Takes Aerosmith Pump 1989 Lightning Strikes Aerosmith Rock in a Hard Place 1982 Der Komimissar After The Fire Der Komimissar 1982 Sirius/Eye in the Sky Alan Parsons Project Eye in the Sky 1982 The Stand Alarm Declaration 1983 Rain in the Summertime Alarm Eye of the Hurricane 1987 Big In Japan Alphaville Big In Japan 1984 Freeway of Love Aretha Franklin Who's Zoomin' Who? 1985 Who's Zooming Who Aretha Franklin Who's Zoomin' Who? 1985 Close (To The Edit) Art of Noise Who's Afraid of the Art of Noise? 1984 Solid Ashford & Simpson Solid 1984 Heat of the Moment Asia Asia 1982 Only Time Will Tell Asia Asia 1982 Sole Survivor Asia Asia 1982 Turn Up The Radio Autograph Sign In Please 1984 Love Shack B-52's Cosmic Thing 1989 Roam B-52's Cosmic Thing 1989 Private Idaho B-52's Wild Planet 1980 Change Babys Ignition 1982 Mr. -

The New York Law School Reporter's Arts and Entertainment Journal, Vol

digitalcommons.nyls.edu NYLS Publications Student Newspapers 4-1986 The ewN York Law School Reporter's Arts and Entertainment Journal, vol IV, no. 4, April 1986 New York Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/newspapers Recommended Citation New York Law School, "The eN w York Law School Reporter's Arts and Entertainment Journal, vol IV, no. 4, April 1986" (1986). Student Newspapers. 117. https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/newspapers/117 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the NYLS Publications at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Newspapers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. The New·York Law School Reporter's 1lll'l,S 1INI) l~N'l,l~ll'l'1IIN)ll~N'I' ,IC) IJllN 11I~ VolIVNo4 • ALL THE NEWS WE CAN FIND • Apr1l1986 llf.)f;I{ 1INI) llf)I~I~: by Dbmne Pine DE1'EN'l'E OF THE EIGH'flES When the arts & entertainment section Sirnplifed - the Home Audio Recording by llya Frenkel first pondered the merits of an article on Act calls for 1) a 1• per minute tax on high With all the talk of possibility of But the real reason behind this the proposed Home Audio Recording Act, quality audio tape; 2) a 5% tax on tape detente in the U.S. - Soviet relations, phenomenon may very well be that with the flood of information which reached recorders and 3) a 25% tax on dual tape cultural exchanges and trade take a the advent of easily-accessible audio, this office looked like so many piles of decks. -

Song Lyrics ©Marshall Mitchell All Rights Reserved

You Don’t Know - Song Lyrics ©Marshall Mitchell All Rights Reserved Freckled Face Girl - Marshall Mitchell © All Rights Reserved A freckled face girl in the front row of my class Headin’ Outta Wichita - Harvey Toalson/Marshall Mitchell On the playground she runs way too fast © All Rights Reserved And I can’t catch her so I can let her know I think she is pretty and I love her so Headin’ outta Wichita; we’re headed into Little Rock tonight And we could’ve had a bigger crowd but I think the band was sounding pretty tight She has pigtails and ribbons in her hair With three long weeks on this road there ain’t nothing left to do, you just listen to the radio When she smiles my heart jumps into the air And your mind keeps a’reachin’ back to find that old flat land you have the nerve to call your home And all through high school I wanted her to know That I thought she was pretty and I loved her so Now, you can’t take time setting up because before you know it’s time for you to play And you give until you’re giving blood then you realize they ain’t a’listenin’ anyway I could yell it in assembly And then you tell yourself that it can’t get worse and it does, and all you can think about is breaking down I could write it on the wall And then you find yourself back on the road following a dotted line to another town Because when I am around her I just cannot seem to speak at all I wanna see a starlit night and I wanna hold my baby tight again While in college I saw her now and then And I’m really tired of this grind and I’d sure like to see the face -

A Comparative Evaluation of Group and Private Piano Instruction on the Musical Achievements of Young Beginners

A Comparative Evaluation of Group and Private Piano Instruction on the Musical Achievements of Young Beginners Pai-Yu Chiu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctoral of Music and Arts University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Craig Sheppard, Chair Donna Shin Steven J. Morrison Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music © Copyright 2017 Pai-Yu Chiu ii University of Washington Abstract A Comparative Evaluation of Group and Private Piano Instruction on the Musical Achievements of Young Beginners Pai-Yu Chiu Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Craig Sheppard School of Music This study compares the relative influence of group and individual piano instruction on the musical achievements of young beginning piano students between the ages of 5 to 7. It also investigates the potential influence on these achievements of an individual teacher’s preference for either mode of instruction, children’s age and gender, and identifies relationships between these three factors and the two different modes of instruction. Forty-five children between the ages of 5 to 7 without previous musical training completed this empirical study, which consisted of 24 weekly piano instruction and a posttest evaluating their musical achievements. The 45 participants included 25 boys and 20 girls. The participants were comprised of twenty-seven 5- year-olds, nine 6-year-olds, and nine 7-year-old participants. Twenty-two children participated in group piano instruction and 23 received private instruction. After finishing 24 weekly lessons, participants underwent a posttest evaluating: (1) music knowledge, (2) music reading, (3) aural iii discrimination, (4) kinesthetic response, and (5) performance skill. -

SMYC 2013 CD Booklet

SPECIAL MULTISTAKE YOUTH CONFERENCE 2013 MUSIC SOUNDTRACK Audio CD_Booklet.indd 1 10/18/2013 9:04:08 AM Stand Chorus Chorus: Joy of Life Singer: Megan Sackett No, I can’t say that I know for certain, but, Singers: Savanna Liechty & Hayden Gillies Every choice, every step, I’m feelin’ somethin’ deep inside my heart Morning sun fill the earth, every moment, I wanna say that I know for certain, Sunlight breaking through the shadows fill the shadows, point my course, set my path but for now it’s a good start. stand lighting all we see fill my soul with light. make me ready. taking in each single moment Sacred light, holy house, I’ve been trying things out a bit, with the air we breath Steady flame, steady guide, loving Father, wanting to know what’s real still so much that lies before us steady voice of peace bind my heart, fill my life I don’t know what will come of it but still so much within our reach lead me through the night. with this promise to stand… if I keep it up I will. of life joy Chorus: Won’t give in, won’t give up And be not moved, together I know there’s someone who after all I can do Every day won’t give out at all Stand makes it all alright brings another moment ‘til my heart is right. In a holy place Then I hear a voice that whispers to me every time Stand… Oh Stand that I’ve known it all my life. -

Pynchon's Sound of Music

Pynchon’s Sound of Music Christian Hänggi Pynchon’s Sound of Music DIAPHANES PUBLISHED WITH SUPPORT BY THE SWISS NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION 1ST EDITION ISBN 978-3-0358-0233-7 10.4472/9783035802337 DIESES WERK IST LIZENZIERT UNTER EINER CREATIVE COMMONS NAMENSNENNUNG 3.0 SCHWEIZ LIZENZ. LAYOUT AND PREPRESS: 2EDIT, ZURICH WWW.DIAPHANES.NET Contents Preface 7 Introduction 9 1 The Job of Sorting It All Out 17 A Brief Biography in Music 17 An Inventory of Pynchon’s Musical Techniques and Strategies 26 Pynchon on Record, Vol. 4 51 2 Lessons in Organology 53 The Harmonica 56 The Kazoo 79 The Saxophone 93 3 The Sounds of Societies to Come 121 The Age of Representation 127 The Age of Repetition 149 The Age of Composition 165 4 Analyzing the Pynchon Playlist 183 Conclusion 227 Appendix 231 Index of Musical Instruments 233 The Pynchon Playlist 239 Bibliography 289 Index of Musicians 309 Acknowledgments 315 Preface When I first read Gravity’s Rainbow, back in the days before I started to study literature more systematically, I noticed the nov- el’s many references to saxophones. Having played the instru- ment for, then, almost two decades, I thought that a novelist would not, could not, feature specialty instruments such as the C-melody sax if he did not play the horn himself. Once the saxophone had caught my attention, I noticed all sorts of uncommon references that seemed to confirm my hunch that Thomas Pynchon himself played the instrument: McClintic Sphere’s 4½ reed, the contra- bass sax of Against the Day, Gravity’s Rainbow’s Charlie Parker passage. -

Project VIP Spring2020 Manuscript

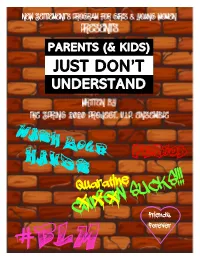

PARENTS (& KIDS) JUST DON’T UNDERSTAND PERIOD Friends Forever #BLM PARENTS (& KIDS) JUST DON’T UNDERSTAND Table of Contents I. Ensemble Photos pg 2 II. Directors’ Note pg 3 III. Scripts: 1. Some Things We Wish Our Parents Would Have Told Us pg 4 2. Period Piece pg 5 3. Sister Sister pg 10 4. What I Wish I could Tell You pg 12 5. Wear What I Want pg 13 6. Party At A Friend’s pg 19 7. Things Heard During Covid-19 Quarantine pg 23 Written by the Ensemble: Jendayi Benjamin, Sariya Western Boyd, Aniyah Campos, Ashanti Campos, Shea Davis, Deshante Deberry, Atseda Johnson, Annalise Rios Mercado, Jaslene Rios Mercado, Tia Sledge & Nakayla Teagle 1 Dear Aniyah, Annalise, Ashante, Atseda, Deshante, Jaslene, Jendayi, Nakayla, Sariya, Shea & Tia: What an interesting semester we have had! We came in talking about parents and all the craziness we had to endure with them … remember watching Will Smith’s video for Parents Just Don’t Understand, and then the corny (but funny) song “Kids” from Bye Bye Byrdie? And improvising (hilarious) inner voice/outer voice conversations? And then our world turned upside down. We’ve never had a semester like this where so much of our work was completed online. No rehearsals, no more theatre games, no more seeing each other in person. Yet despite all this we came up with some great scripts and poems to show how parent and child relationships work in 2020. We loved the energy you brought to the group. Thank you for all your hard work in class and online. -

Fears for the Future April 2010

Fears for the Future April 2010 The Verdadera staff encourages you to discuss and explore the issues and stories, as the publication aims not only to offer an outlet for expression, but to improve our lives. Keep in mind that the emotions that flow through the text and the feelings behind the words could be those of your child, your classmate, or your best friend. Things to consider: Where do our fears for the future come from? How do we cope with the fear? Are my fears based on facts or the unknowns? Does this fear help or hurt us? ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Student Submissions You need to go to college. End of story. That’s Maybe I should be scared for college. But I’m the way my mom talks to me. The way my mom talks to not. Because whatever, I’ll get in somewhere hopefully; me, it seems as if college is the end of my life, as if get some kind of decent job, live in a small apartment everything I’ve done for my whole life is to get to maybe, I don’t need any luxuries I just want a simple college. And frankly, I feel that I don’t nececssarily life. need to go to college. I guess thought is what scares me What I’m scared for is having a family. And about the future. I feel like ive been brainwashed to a living alone or getting married then having my spouse point in which im not gonna be prepared for what file for divorce. -

The Mercurian Volume 3, No

The Mercurian A Theatrical Translation Review Volume 3, Number 4 Editor: Adam Versényi ISSN 2160-3316 The Mercurian is named for Mercury who, if he had known it, was/is the patron god of theatrical translators, those intrepid souls possessed of eloquence, feats of skill, messengers not between the gods but between cultures, traders in images, nimble and dexterous linguistic thieves. Like the metal mercury, theatrical translators are capable of absorbing other metals, forming amalgams. As in ancient chemistry, the mercurian is one of the five elementary “principles” of which all material substances are compounded, otherwise known as “spirit”. The theatrical translator is sprightly, lively, potentially volatile, sometimes inconstant, witty, an ideal guide or conductor on the road. The Mercurian publishes translations of plays and performance pieces from any language into English. The Mercurian also welcomes theoretical pieces about theatrical translation, rants, manifestos, and position papers pertaining to translation for the theatre, as well as production histories of theatrical translations. Submissions should be sent to: Adam Versényi at [email protected] or by snail mail: Adam Versényi, Department of Dramatic Art, CB# 3230, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3230. For translations of plays or performance pieces, unless the material is in the public domain, please send proof of permission to translate from the playwright or original creator of the piece. Since one of the primary objects of The Mercurian is to move translated pieces into production, no translations of plays or performance pieces will be published unless the translator can certify that he/she has had an opportunity to hear the translation performed in either a reading or another production-oriented venue.