Malcolm Muggeridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malcolm Muggeridge the Infernal Grove

e FONTANA MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE THE INFERNAL GROVE 'The wit sparkles on almost every page' BERNARD LEVIN Chronicles of Wasted Time Part 2 The Infernal Grove Malcolm Muggeridge was born in 1903 and educated at Selhurst Grammar School and Selwyn College, Cambridge. After lecturing at the Egyptian University in Cairo, he joined the editorial staff of the Man chester Guardian in 1930, and was Moscow Corre spondent for this paper from 1932-3. In the war of 1939-45 he served as an Intelligence officer in North Africa, Moz.ambique, Italy and France, being seconded to MI6, the wartime version of the Secret Service. He ended up in Paris as Liaison Officer with the French Securite Militaire, and was awarded the Legion of Hon0ur (Chevalier), the Croix de Guerre with Palm and the Medaille de la Reconnaissance Fran9aise. His career as a journalist included a spell' as Washington Correspondent of the Daily Telegraph from 1946-7, and Deputy Editorship from 1950-52. He was Editor of Punch from 1953-7 and Rector of Edinburgh University from 1967-8. He has written numerous books since the early '30s, including Some thing Beautiful for God, Jesus Rediscovered, Tread Softly for you Tread on my Jokes, and The Thirties. He lives in Robertsbridge, Sussex. Volume I of Chronicles of Wasted Time, The Green Stick, is abo available from Fontana, MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE Chronicles of Wasted Time Part 2 The Infernal Grove Till I tum from Female Love, And root up the Infernal Grove, I shall never worthy be To step into Eternity Blake FONTA NA/Collins First published by William Collins Sons & Co. -

Streams of Civilization: Volume 2

Copyright © 2017 Christian Liberty Press i Streams Two 3e TEXT.indb 1 8/7/17 1:24 PM ii Streams of Civilization Volume Two Streams of Civilization, Volume Two Original Authors: Robert G. Clouse and Richard V. Pierard Original copyright © 1980 Mott Media Copyright to the first edition transferred to Christian Liberty Press in 1995 Streams of Civilization, Volume Two, Third Edition Copyright © 2017, 1995 Christian Liberty Press All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without written permission from the publisher. Brief quota- tions embodied in critical articles or reviews are permitted. Christian Liberty Press 502 West Euclid Avenue Arlington Heights, Illinois 60004-5402 www.christianlibertypress.com Copyright © 2017 Christian Liberty Press Revised and Updated: Garry J. Moes Editors: Eric D. Bristley, Lars R. Johnson, and Michael J. McHugh Reviewers: Dr. Marcus McArthur and Paul Kostelny Layout: Edward J. Shewan Editing: Edward J. Shewan and Eric L. Pfeiffelman Copyediting: Diane C. Olson Cover and Text Design: Bob Fine Graphics: Bob Fine, Edward J. Shewan, and Lars Johnson ISBN 978-1-629820-53-8 (print) 978-1-629820-56-9 (e-Book PDF) Printed in the United States of America Streams Two 3e TEXT.indb 2 8/7/17 1:24 PM iii Contents Foreword ................................................................................1 Introduction ...........................................................................9 Chapter 1 European Exploration and Its Motives -

“Creating Many Ripples” Homily for 23 Sunday of Ordinary Time

1 “Creating many Ripples” Homily for 23rd Sunday of Ordinary Time September 4th 2016 Wisdom of Solomon 9:13–18b Psalm 90:3–6, 12–17 Philemon 9–10, 12–17 Gospel Luke 14:25–33 In December 1982 Malcolm Muggeridge became a Roman Catholic. What made this event so significant was the fact that for much of his life, he was either an atheist, in his younger years, or an agnostic, during midlife. He was born in 1903 and was received into the Church at age 79. With the passing of the years he came to have a greater respect for Christianity but because of his love for the deadly sins, especially pride, gluttony and lust he did not think he could rightly represent the Christian faith and so did not convert. By the nineteen fifties he was one of the best known British journalists in the world, a status that increased even more after the advent of TV. In the late sixties he went to Kolkata to meet Mother Theresa. Instead of being angry, Muggeridge’s heart melted as Mother Teresa forced him to wait for hours while she tended to the sick and the dying. Instead of having to fend off the intensity of this tiny nun’s love for the poorest of the poor, he embraced her indelibly by writing Something Beautiful for God. After his conversion Muggeridge remembered Mother Teresa of Kolkata, whose selfless work for India’s destitute he first told the world about, had a dramatic transforming effect on his life. Seeing the light of God illuminate the nun’s wizened face, seeing her complete trust in God, Muggeridge saw as never before “the pathetic condition of his worldly cynicism”. -

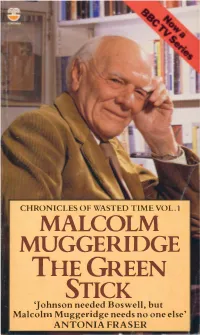

MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE THEGREEN STICK 'Johnson Needed Boswell, but Malcolm Muggeridge Needs No One Else' ANTONIA FRASER Chronicles of Wasted Time Part 1

CHRONICLES OF WASTED TIME VOL.1 MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE THEGREEN STICK 'Johnson needed Boswell, but Malcolm Muggeridge needs no one else' ANTONIA FRASER Chronicles of Wasted Time Part 1 The Green Stick Malcolm Muggeridge was born in 1903 and educated . at Selhurst Grammar School and Selwyn College, Cambridge. After lecturing at the Egyptian University in Cairo, he joined the editorial staff of the Man chester Guardian in 1930, and was Moscow Corre spondent for this paper from 1932-3. In the war of 1939-45 he served as an Intelligence. officer in North Africa, Mozambique, Italy and France, being seconded to M I6, the wartime version of the Secret Service. He ended up in Paris as Liaison Officer with the French Securite Militaire, and was awarded the Legion of Honour (Chevalier), the Croix de Guerre with Palm and the Medaille de la Reconnaissance Frani;:aise. His career as a journalist included a spell as Washington Correspondent of the Daily Telegraph from 1946-7, and Deputy Editorship from 1950-52. He was Editor of Punch from 1953-7 and Rectm of Edinburgh University from 1967-8. He has written numerous books since the early '30s, including Some thing Beautiful for God, Jesus Rediscovered, Tread Softly for you Tread on my Jokes, and The Thirties. He lives in Robertsbridge, Sussex. MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE Chronicles of Wasted Time Part I The Green Stick I used to believe that there was a green stick, buried on the edge of a ravine in the old Zakaz forest at Yasnaya Polyana, on which words were carved that would destroy all the evil in the hearts of men and bring them everything good. -

Ethical Record

The ISSN 0014- 1690 Ethical Record Vol. 96 No. 9 OCTOBER 1991 CONTENTS Page Saint Mugg 3 Relation between Brain vc Consciousness 7 Book Review 12 Letters 14 London Student Skeptics 15 Forthcoming Events 16 Editorial This issue of The Ethical Record is unusually Perhaps the strongest reason for retaining short due to an absence of suitable material. the present title is that of tradition. But this is Due to the economics and technology of no reason at all. It is simply to say that things printing the journal must be in increments of have always been thus, so they must remain 8 pages. so. Even if it were the case that a particular usage had always been so this would not of Three years ago Nicolas Walter suggested itself be a good enough reason for retaining it. that it was time to consider changing the But such appeals to tradition usually arbitrarily name of the South Place Ethical Society ('A stop in historical reference at the moment Century of the Ethical Movement', ER, when that particular usage itself became September '88). This suggestion seemed to current. This is so in the case of the present elicit little response. I will repeat this proposal name for the Society. It was not always called and invite readers to reply: by its present name and need not continue to The premises of the Society are no longer be so. -at South Place, so 'South Place' is no longer an accurate qualification of 'Ethical Society'. But then again: surely the 'it' itself has changed. -

Episode 3: Mother

Episode 3: Mother ERIKA LANTZ: Mother Teresa was always traveling. Flying here. Flying there. I tend to think of her as living a spartan life, but, of course, she took planes like anyone else. Mary Johnson remembers this one time in particular: The two of them flew from Rome to Sweden. Mary was Mother’s traveling companion and assistant for the trip. MARY JOHNSON: We were going there for an ecumenical conference where Mother was going to be honored and was going to give a talk. ERIKA: They boarded the plane in their blue and white saris. Mary also packed two heavy boxes of “Miraculous Medals” -- these small religious tokens that Mother Teresa would kiss and hand out to people. Mary and Mother Teresa settled into their seats in first class. They’d booked economy, but Mary says airlines always upgraded the tickets. MARY: They're trying to avoid all that commotion that would happen if people knew Mother Teresa was on the plane. ERIKA: Mary says Mother Teresa pulled on the sleeve of one of the flight attendants and said: MARY: “All that extra food, you know, that people aren't eating, that you're going to have to throw away anyway -- could you give it to me, and I will use it for the poor?” ERIKA: The flight attendant looked hesitant, awkward. She explained they had to throw the food waste away; it was against the rules to keep it. MARY: And she said, “Oh no, just tell them Mother Teresa needs it for the poor. They won't make any fuss for you.” And anyway, long story short, eventually she went around with a big, black trash bag collecting things from people, and, of course, that's how people came to know that Mother Teresa was on the plane, and then they all started to come one by one and standing next and Mother would sign things for them and kiss the medal and give it to them and pray with them and all the rest of it. -

English Or Anglo-Indian?: Kipling and the Shift in the Representation of the Colonizer in the Discourse of the British Raj

English or Anglo-Indian?: Kipling and the Shift in the Representation of the Colonizer in the Discourse of the British Raj Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Catherine Elizabeth Hart, M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Clare Simmons, Advisor Jill Galvan Amanpal Garcha Pranav Jani Copyright by Catherine Elizabeth Hart 2012 Abstract Using Rudyard Kipling as the focal point, my dissertation examines nineteenth- century discourse on English identity and imperialism through literature of the British Raj written in the 1840s through the 1930s. In my analysis of this literature, I identify a shift in the representation of the colonizer between English and Anglo-Indian in four distinct historical moments: pre-Rebellion (1857), post-Rebellion, the fin de siècle, and post- World War I. While the term Anglo-Indian can be used as a simple means of categorization—the Anglo-Indian is the English colonizer who lives in and conducts imperial work in India as opposed to one of the other British colonies—it also designates a distinct cultural identity and identifies the extent to which the colonizer has been affected by India and imperialism. As such, the terms Anglo-Indian and English, rather than being interchangeable, remain consistently antithetical in the literature with one obvious exception: the Kipling canon. In fact, it is only within the Kipling canon that the terms are largely synonymous; here, the Anglo-Indian colonizer is represented not only as a positive figure but also as a new and improved breed of Englishman. -

Gandhi and Tolstoy. a Study of Gandhi's Intellectual Development Considered Within the Framev,Ork of Hermeneutic Philosophy

Gandhi and Tolstoy. A study of Gandhi's Intellectual Development considered within the framev,ork of Hermeneutic Philosophy. GARTH ABRAHAM Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in the Department of History, Faculty of Arts, at the University of Natal, Durban. DECEMBER, 1982. PREFACE ii The intention of this dissertation is to assess the continuous and abiding influence of Tolstoy on Gandhi's intellectual development while in South Africa. With this objective in mind the hermeneutic philosophy of interpretation and understanding has been presented in the Introduction as a schema in terms of which Gandhi's intellectual development may be more readily understood. Hermeneutics attempts to expose the oft unrecognised fact that it is impossible to speak of 'presuppositionless' understanding It refutes the thesis that Gandhi's philosophy was either Hindu or Christian. Rather Gandhi's interpretation of Hinduism while in South Africa should be seen in terms of his familiarity with the 'Christian life-conception' of Tolstoy and the Theosophy of his London circle of acquaintances. As an attempt at an intellectual history it has also been necessary to relate Gandhi's development to historical reality in order to maintain some sort of chronological development in his thought. Furthermore certain key events in Gandhi's life have been discussed in some detail as they do to a considerable degree determine both the depth of his philosophy in terms of the manner in which he attempts to relate theory to praxis - and the direction his philosophy takes consequent to the event. With regard to source material for an intellectual history one has been forced to rely heavily on autobiographical material. -

The Realist and Paul Krassner's 1960S Terry Joel Wagner Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 "To liberate communication": the Realist and Paul Krassner's 1960s Terry Joel Wagner Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Wagner, Terry Joel, ""To liberate communication": the Realist and Paul Krassner's 1960s" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 3562. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3562 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “TO LIBERATE COMMUNICATION:” THE REALIST AND PAUL KRASSNER’S 1960S A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History By Terry Joel Wagner B.A., Rice University, 2002 August 2010 Acknowledgements This project would have been inconceivable without the regular encouragement and aid of my parents, Desley Noonan-Wagner and Robert Wagner. I thank them not only for providing a sounding board for the ideas explored in this project, and for research assistance, but also for a lifetime of putting my education foremost. Thanks especially to my mother for teaching me how to write. I also want to acknowledge my sister, who has the zany idea that what I study is cool. -

The Spire the Beacon on the Seine

The Spire The Beacon on the Seine February 2012 The American Church in Paris www.acparis.org 65, Quai d’Orsay, 75007 Paris, France Thoughts From Rev. Dr. Scott Herr Senior Pastor Dear Members and Friends, Lent for me stirs ambiguous feelings. I am that others might simply live. One of Stott’s inclined toward a guilty conscience, so research assistants was Mark Labberton, loading on more religious “duties” is generally who spoke at the ACP last year. As the not inspiring or uplifting to me. On the other Director of the Lloyd John Ogilvie Institute hand, I love the original meaning of Lent for Preaching at Fuller Seminary, he is which is simply “Spring.” Lent is the church’s starting what he calls “Micah Groups” to Holy Spring, a time when we prepare for a encourage preachers to think about how and season of spiritual renewal and growth. It is what we are communicating. Mark invited our preparation time for the promised new pastors from South Africa, Egypt, Turkey, the life paradoxically embedded in the mystery of Netherlands and England and made it clear the Crucifixion and Resurrection. My that Micah Groups are about embodying the understanding of the gospel is that the ethic of Micah 6:8: “What does the Lord Church’s season of renewal and growth is require of you, but to do justice, love mercy better measured not as much in how we are and walk humbly with your God.” The doing as a congregation, but how our question is not about how to get a “Wow!” congregation is doing in impacting Paris and response to Sunday worship, but rather the world. -

The Wit and Wisdom of M Crist Fleming

ISDOM W O F TASIS THE IT AND The American School in Switzerland W T HE W IT AND W ISDOM OF M ARY C RIST F LEMING TASIS The American School in Switzerland THE W IT AND W ISDOM OF M ARY C RIST F LEMING Lyle D. Rigg, Editor * MMXI To Mary Crist Fleming Lynn Fleming Aeschliman Anita Russell Rigg Sharon Creech Rigg For always finding the right words, when needed most. CONTENTS Introduction XIII Acknowledgments XVIII Speech to Alumni 1 Beauty and The Arts 7 Education and Wisdom 13 Dreams 25 Internationalism 31 Caring 37 Humor 43 Setbacks 51 Challenges 55 Leadership 63 Making a Difference 67 Age and Aging 73 Values 81 Appendix 87 Biography 97 About the Editor 105 VII Education is service and I believe we are put on this earth to make some contribution, to try to leave it a little better place than we found it. Interview with John Amis, 1990 IX When I look at your year of graduation, I am all too vividly reminded that in only three months I will be 97! Looking back on all those years, all I can wish for you is that you have a dream – a big dream, and that you work all your life to make that dream come true! For in so doing you will live every moment of your life to the fullest and your greatest satisfaction will come when you share that dream, and through sharing you give others a better life, too. As sung in (the musical) South Pacific, “if you don’t have a dream, how can you make a dream come true?” So my wish and my prayers for you are that you dream big and bold so that you as an individual make a difference – a difference that makes the world a better place in small and large ways for all the humans who inhabit it. -

D. H. Lawrence Interviews and Recollections

D. H. Lawrence Interviews and Recollections Volume 1 Also by Norman Page Dickens: Bleak House (editor) Dickens: Hard Times, Great Expectations and Our Mutual Friend-Casebook (editor) E. M. Forster's Posthumous Fiction Hardy: Jude the Obscure (editor) Speech in the English Novel Tennyson: Interviews and Recollections (editor) The Language of Jane Austen Thomas Hardy Thomas Hardy: the Writer and his Background (editor) Wilkie Collins: the Critical Heritage (editor) D. H. LAWRENCE Interviews and Recollections Volume 1 Edited by Norman Page Professor of English University of Alberta Selection and editorial matter © Norman Page 1981 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1981 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission First published 1981 by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD London and Basingstoke Companies and representatives throughout the world First published in the USA 1981 by BARNES & NOBLE BOOKS 81, Adams Drive Totowa, New Jersey 07512 ISBN 978-1-349-04822-9 ISBN 978-1-349-04820-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-04820-5 BARNES & NOBLES ISBN 978-0-389-20031-4 Contents Acknowledgements Vll Introduction IX A Lawrence Chronology xm INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS Lawrence's Boyhood W. E. Hopkin Mother and Son May Holbrook 5 Family Life Ada Lawrence 8 'I am Going to be an Author' W. E. Hopkin 10 At Haggs Farm Ada Lawrence II The Friendship with 'Miriam' Jessie Chambers 14 Adolescence J.D. Chambers 32 Recollections of a 'Pagan' George H. Neville 36 'Jehovah Junior'