Roger Coronini.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inner 24 India Pharma & Healthcare Fund Low

Tata India Pharma & Healthcare Fund (An open ended equity scheme investing in Pharma and Healthcare Services Sector) As on 30th June 2020 PORTFOLIO INVESTMENT STYLE Company name No. of Market Value % of Company name No. of Market Value % of Primarily focuses on investment in at least 80% of its net Shares Rs. Lakhs Assets Shares Rs. Lakhs Assets assets in equity/equity related instruments of the Equity & Equity Related Total 23733.48 98.49 companies in the Pharma & Healthcare sectors in India. Healthcare Services Other Equities^ 380.78 1.58 INVESTMENT OBJECTIVE Narayana Hrudayalaya Ltd. 382720 1025.69 4.26 Repo 871.61 3.62 The investment objective of the scheme is to seek long Healthcare Global Enterprises Ltd. term capital appreciation by investing atleast 80% of its 410000 503.48 2.09 Portfolio Total 24605.09 102.11 net assets in equity/equity related instruments of the Apollo Hospitals Enterprise Ltd. 32500 438.70 1.82 Net Current Liabilities -507.01 -2.11 companies in the pharma & healthcare sectors in Pharmaceuticals India.However, there is no assurance or guarantee that Net Assets 24098.08 100.00 the investment objective of the Scheme will be Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. 870100 4115.14 17.08 achieved.The Scheme does not assure or guarantee any Dr Reddys Laboratories Ltd. 98000 3866.05 16.04 returns. Divi Laboratories Ltd. 102500 2335.87 9.69 DATE OF ALLOTMENT Lupin Ltd. 223000 2033.31 8.44 December 28, 2015 Ipca Laboratories Ltd. 95000 1590.68 6.60 Cipla Ltd. 230000 1472.58 6.11 FUND MANAGER Aurobindo Pharma Ltd. -

Annual-Report-2018-1

Index Corporate Overview 2-33 About NATCO Pharma 2 Key milestones 6 Business highlights FY 2018-19 8 Key performance indicators 10 Megatrends 12 Management message 14 Building businesses in diverse markets 18 Leveraging synergies through diversity 20 Advancing R&D diversification 22 Board of Directors and Key 24 Management Team Risk framework and mitigation 26 strategy Corporate social responsibility (CSR) 28 Environment, health & safety (EHS) 32 Key numbers of FY 2018-19 on consolidated basis Statutory Reports 34-98 Total Revenue PAT Management Discussion and Analysis 34 Board's Report 43 ` 22,247 million ` 6,444 million Corporate Governance Report 71 Business Responsibility Report 90 EBITDA Basic EPS ` 9,250 million ` 34.98 Financial Statements 99-192 Disclaimer Standalone Financials 99 In this Annual Report, we have disclosed forward-looking information to enable investors to comprehend our prospects and take investment decisions. This report and Consolidated Financials 147 other statements - written and oral - that we periodically make contain forward-looking statements that set out anticipated results based on the management’s plans and assumptions. We have tried, wherever possible, to identify such statements by using words such as ‘anticipate’, ‘estimate’, ‘expects’, ‘projects’, ‘intends’, ‘plans’, ‘believes’, and Notice 193 words of similar substance in connection with any discussion of future performance. We cannot guarantee that these forward-looking statements will be realised, although we believe we have been prudent in our assumptions. The achievements of results are subject to risks, uncertainties and even inaccurate assumptions. Should known or unknown risks or uncertainties materialise, or should underlying assumptions prove inaccurate, actual results could vary materially from those anticipated, estimated or projected. -

Natco Pharma Limited

Placement Document Not for Circulation Private and Confidential Serial No. [●] NATCO PHARMA LIMITED Originally incorporated as Natco Fine Pharmaceuticals Private Limited on September 19, 1981, the name of our Company was changed to “Natco Pharma Limited” on December 30, 1994 under the Companies Act, 1956. The registered office of our Company is at Natco House, Road no. 2, Banjara Hills, Hyderabad – 500 034, Telangana; Telephone: +91 40 2354 7532; Fax: +91 40 2354 8243; Email: [email protected]; Website: www.natcopharma.co.in; Corporate identification number:L24230TG1981PLC003201. Natco Pharma Limited (our “Company” or the “Issuer”) is issuing 1,600,000 equity shares of face value of Rs. 10 each (the “Equity Shares”) at a price of Rs. 2,130.55 per Equity Share, including a premium of Rs. 2,120.55 per Equity Share, aggregating to Rs. 3,408.88 million (the “Issue”). ISSUE IN RELIANCE UPON SECTION 42 OF THE COMPANIES ACT, 2013, AS AMENDED, READ WITH RULES MADE THEREUNDER, AND CHAPTER VIII OF THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE BOARD OF INDIA (ISSUE OF CAPITAL AND DISCLOSURE REQUIREMENTS) REGULATIONS, 2009, AS AMENDED (THE “SEBI ICDR REGULATIONS”). THIS ISSUE AND THE DISTRIBUTION OF THIS PLACEMENT DOCUMENT IS BEING MADE TO QUALIFIED INSTITUTIONAL BUYERS (“QIBs”) AS DEFINED IN THE SEBI ICDR REGULATIONS IN RELIANCE UPON CHAPTER VIII OF THE SEBI ICDR REGULATIONS, AS AMENDED AND SECTION 42 OF THE COMPANIES ACT, 2013, AS AMENDED, AND RULES MADE THEREUNDER. THIS PLACEMENT DOCUMENT IS PERSONAL TO EACH PROSPECTIVE INVESTOR AND DOES NOT CONSTITUTE AN OFFER OR INVITATION OR SOLICITATION OF AN OFFER TO THE PUBLIC OR TO ANY OTHER PERSON OR CLASS OF INVESTORS WITHIN OR OUTSIDE INDIA OTHER THAN QIBs. -

Company Reliance Industries Limited Tata Consultancy Services

Top 1000 Private Sector Companies (Rank-wise List) Company Reliance Industries Limited Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) Infosys Technologies Ltd Wipro Limited Bharti Tele-Ventures Limited ITC Limited Hindustan Lever Limited ICICI Bank Limited Housing Development Finance Corp. Ltd. TATA Steel Limited Ranbaxy Laboratories Limited HDFC Bank Ltd Tata Motors Limited Larsen & Toubro Limited (L&T) Satyam Computer Services Ltd. Maruti Udyog Limited Bajaj Auto Ltd. HCL Technologies Ltd. Hero Honda Motors Limited Hindalco Industries Ltd Reliance Energy Limited Grasim Industries Limited Jet Airways (India) Ltd. Sun Pharmaceuticals Industries Ltd Cipla Ltd. Gujarat Ambuja Cements Ltd. Videsh Sanchar Nigam Limited The Tata Power Company Limited Sterlite Industries (India) Ltd. Associated Cement Companies Ltd. Nestlé India Ltd. Hindustan Zinc Limited GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals Limited Siemens India Ltd. Motor Industries Company Limited Mahindra & Mahindra Limited UTI Bank Ltd. Zee Telefilms Limited Bharat Forge Limited ABB Limited i-Flex Solutions Ltd. Dr. Reddy's Laboratories Ltd. Nicholas Piramal India Limited Kotak Mahindra Bank Limited Reliance Capital Ltd. Ultra Tech Cement Ltd. Patni Computer Systems Ltd. Wockhardt Limited Indian Petrochemicals Corporation Limited Biocon India Limited Essar Oil Limited. Asian Paints Ltd. Dabur India Limited Jaiprakash Associates Limited JSW Steel Limited Tata Chemicals Limited Tata Tea Limited Tata Teleservices (Maharashtra) Limited The Indian Hotels Co. Ltd. Glenmark Pharmaceuticals Limited NIRMA Limited Jindal Steel & Power Ltd HCL Infosystems Ltd. Cadila Healthcare Limited Colgate-Palmolive (India) Limited The Great Eastern Shipping Company Limited Aventis Pharma India Ltd Ashok Leyland Limited Pantaloon Retail (India) Limited Indian Rayon And Industries Limited Financial Technologies (India) Ltd United Phosphorus Limited Matrix Laboratories Limited Sesa Goa Limited Lupin Ltd Cummins India Limited Crompton Greaves Limited. -

Model Portfolio Update

Model Portfolio update September 2, 2016 LatestDeal Team Model – PortfolioAt Your Service Large cap Midcap Name of the company Weightage(%) Name of the company Weightage(%) Auto 15.0 Aviation 6.0 Tata Motor DVR 4.0 Interglobe Aviation 6.0 Bosch 3.0 Auto 6.0 Maruti 5.0 Bharat Forge 6.0 EICHER Motors 3.0 BFSI 6.0 BFSI 25.0 Bajaj Finserve 6.0 HDFC Bank 8.0 Capital Goods 6.0 Axis Bank 3.0 Bharat Electronics 6.0 HDFC 8.0 Cement 6.0 Bajaj Finance 6.0 Ramco Cement 6.0 Capital Goods 4.0 Consumer 30.0 L & T 4.0 Symphony 606.0 Cement 4.0 UltraTech Cement 4.0 Supreme Ind 6.0 FMCG/Consumer 18.0 Kansai Nerolac 6.0 Dabur 5.0 Pidilite 6.0 Marico 4.0 Rallis 6.0 Asian Paints 5.0 Infrastructure 8.0 Nestle 4.0 NBCC 8.0 IT 18. 0 Logistics 606.0 Infosys 10.0 Container Corporation of India 6.0 TCS 8.0 Pharma 20.0 Media 2.0 Natco Pharma 6.0 Zee Entertainment 2.0 Torrent Pharma 6.0 Pharma 14.0 Biocon 8.0 Lupin 6.0 Textile 6.0 DRddDr Reddys 505.0 Arvind 6.0 Aurobindo Pharma 3.0 Total 100.0 Total 100.0 • Exclusion - ITC, Wipro and Reliance Industries • Exclusion – Nestlé shifted to Large cap • Inclusion – Dabur, increased weight in Maruti, Marico, Bajaj Finance & • Inclusion - Biocon UltraTech. Also Nestlé transferred from Midcap to Large cap Source: Bloomberg, ICICIdirect.com Research *Diversified portfolio - Combination of 70% large cap and 30% midcap portfolio OutperformanceDeal Team – At continues Your Service across all portfolios… • Our indicative large cap equity model portfolio has continued to deliver an • In the large cap space, we continue to remain positive on auto, impressive return (inclusive of dividends) of 108.5% since its inception infrastructure & cement. -

Chronic Hepatitis C Treatment Expansion: Generic Manufacturing

CHRONIC HEPATITIS C TREATMENT EXPANSION Generic Manufacturing for Developing Countries Gilead is working to enable access to its medicines for all people who can benefit from them, regardless of where they live or their economic means. Snapshot Gilead has agreements with 11 There are 103 million Gilead also offers its branded Indian companies to manufacture people living with hepatitis C hepatitis C medicines at a generic hepatitis C medicines for in these developing countries significantly reduced flat 101 developing countries price in these countries For more than a decade, Gilead has been working in partnership with governments, healthcare systems, providers, public health entities and generic manufacturers to make its HIV and hepatitis B medicines available worldwide. Currently, 8 million people living with HIV in developing countries receive Gilead antiretroviral medicines through these efforts. Gilead is now working to help ensure broad access to its hepatitis C medicines in developing countries. Gilead has signed agreements with 11 India-based generic pharmaceutical manufacturers to develop sofosbuvir, the single tablet regimen of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir and the investigational single tablet regimen of sofosbuvir/ velpatasvir for distribution in 101 developing countries. Gilead has also signed agreements with three local generic manufacturers for in-country production and distribution of our hepatitis C medicines in Egypt and Pakistan. Generic Agreements Under the licensing agreements, Gilead’s Indian generic manufacturing partners have the right to develop and market generic versions of Gilead HCV medicines in certain developing countries. The generic drug companies may set their own prices and receive a complete technology transfer of the Gilead manufacturing process, enabling them to scale up production as quickly as possible. -

List of Nodal Officer

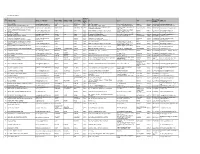

List of Nodal Officer Designa S.No tion of Phone (With Company Name EMAIL_ID_COMPANY FIRST_NAME MIDDLE_NAME LAST_NAME Line I Line II CITY PIN Code EMAIL_ID . Nodal STD/ISD) Officer 1 VIPUL LIMITED [email protected] PUNIT BERIWALA DIRT Vipul TechSquare, Golf Course Road, Sector-43, Gurgaon 122009 01244065500 [email protected] 2 ORIENT PAPER AND INDUSTRIES LTD. [email protected] RAM PRASAD DUTTA CSEC BIRLA BUILDING, 9TH FLOOR, 9/1, R. N. MUKHERJEE ROAD KOLKATA 700001 03340823700 [email protected] COAL INDIA LIMITED, Coal Bhawan, AF-III, 3rd Floor CORE-2,Action Area-1A, 3 COAL INDIA LTD GOVT OF INDIA UNDERTAKING [email protected] MAHADEVAN VISWANATHAN CSEC Rajarhat, Kolkata 700156 03323246526 [email protected] PREMISES NO-04-MAR New Town, MULTI COMMODITY EXCHANGE OF INDIA Exchange Square, Suren Road, 4 [email protected] AJAY PURI CSEC Multi Commodity Exchange of India Limited Mumbai 400093 0226718888 [email protected] LIMITED Chakala, Andheri (East), 5 ECOPLAST LIMITED [email protected] Antony Pius Alapat CSEC Ecoplast Ltd.,4 Magan Mahal 215, Sir M.V. Road, Andheri (E) Mumbai 400069 02226833452 [email protected] 6 ECOPLAST LIMITED [email protected] Antony Pius Alapat CSEC Ecoplast Ltd.,4 Magan Mahal 215, Sir M.V. Road, Andheri (E) Mumbai 400069 02226833452 [email protected] 7 NECTAR LIFE SCIENCES LIMITED [email protected] SUKRITI SAINI CSEC NECTAR LIFESCIENCES LIMITED SCO 38-39, SECTOR 9-D CHANDIGARH 160009 01723047759 [email protected] 8 ECOPLAST LIMITED [email protected] Antony Pius Alapat CSEC Ecoplast Ltd.,4 Magan Mahal 215, Sir M.V. Road, Andheri (E) Mumbai 400069 02226833452 [email protected] 9 SMIFS CAPITAL MARKETS LTD. -

Resisting the Usual. Natco Pharma Limited

31st ANNUAL REPORT 2013-14 Resisting the usual. Natco Pharma Limited Natco Pharma Limited Natco House, Road No.2, Banjara Hills, Hyderabad 500 034. www.natcopharma.co.in Corporate Information Board of Directors Resisting Shri V.C. Nannapaneni Chairman & Managing Director Shri T V Rao Director – Nominee of Export-Import Bank of India the usual. Shri G.S. Murthy Director Dr. B.S. Bajaj Director Shri Rajeev Nannapaneni Vice Chairman & Chief Executive Officer It would be easy being the Dr. P. Bhaskara Narayana Director & Chief Financial Officer usual pharmaceutical company. Dr. A.K.S. Bhujanga Rao President (R&D and Technical) Shri D.G. Prasad Director Moreover, at Natco Pharma, we (w.e.f. 13th February, 2014) have selected to resist the usual. Shri. Vivek Chhachhi Director (w.e.f 7th January, 2014) Shri Tarun Khanna Alternate Director to Shri Vivek Chhachhi Shri Nitin Jagannath Deshmukh Director (till 28th January, 2014) CS. M. Adinarayana Bankers Company Secretary & Allahabad Bank Vice President (Legal & Corporate Affairs) State Bank of India Corporation Bank Oriental Bank of Commerce YES Bank Ltd. Axis Bank Ltd. Citibank N.A. Auditors Registered Office M/s. Walker, Chandiok & Co. LLP Natco House, Chartered Accountants, Road No.2, Banjara Hills, 7th Floor, Block III, White House Hyderabad 500 033. Kundan Bagh, Begumpet, www.natcopharma.co.in Contents Corporate identity 2 Financial Highlight 4 Chairman’s address 14 Hyderabad 500 016 Corporate Social Responsibility 35 Directors’ Report 38 Forward-looking statements Forward-looking are forward-looking. This document contains statements about expected future events and financial operating results of Natco Pharma Limited , which There is significant By their nature, forward-looking statements require the Company to make assumptions and are subject inherent risks uncertainties. -

Natco Pharma Ltd. US Filings Review

Natco Pharma Ltd. US filings review Natco Pharma (NATCO) is ~ INR 2000 Crore revenue Pharmaceutical company with exposure to Vikas Sonawale the US generics (40%, FY19) and India Formulations (37%) segments. The company followed a Research Analyst differentiated strategy compared to other generic pharma players for both the US & Indian [email protected] markets and has been successful in executing it. It pursued litigation driven – specific product opportunities in the US. For the Indian market, it remained focused on time-specific opportunities (like Hep-C) coupled with narrower therapy (Oncology) approach vs broadly diversified model of CMP: INR 625 other companies. It has had a phase of strong profit growth especially over FY16-18 on the back of a low base & successful monetisation of opportunities. FY19 saw some decline, FY20E would M. Cap: INR 11,377 Crs most likely see earnings depression. Near term earnings recovery is pegged to a few product 52-W H/L: INR 707/482 opportunities going right. There are certain 7catalysts in FY22E, FY23E and FY27E. The company is diversifying into agro-chemicals where it is trying to replicate its Pharma success. The company Rating: Not Rated has a strong balance sheet (supported by QIP) with INR 740 Crs cash on it. A large part of the earnings cycle is reflected in the share price performance. Valuations have also softened. This note is focused on evaluating filings made for the US business. Differentiated model: Natco’s success in the US market was on the back of four key opportunities gTamiflu, gDoxil, gFosrenol, gCopaxone launched by its partners over a 11-month period from Dec-2016 to Oct-2017. -

Natco Pharma Limited

Natco Pharma Limited Feb 2016 Strictly Private and Confidential Important Disclosure This presentation has been prepared by Natco Pharma Limited (the “Company”) solely for information purposes without regard to any specific objectives, financial situations or informational needs of any particular person. This presentation should not be construed as legal, tax, investment or other advice. This presentation is confidential, being given solely for your information and for your use, and may not be copied, distributed or disseminated, directly or indirectly, in any manner. Furthermore, no person is authorized to give any information or make any representation which is not contained in, or is inconsistent with, this presentation. Any such extraneous or inconsistent information or representation, if given or made, should not be relied upon as having been authorized by or on behalf of the Company. The distribution of this presentation in certain jurisdictions may be restricted by law. Accordingly, any persons in possession of this presentation should inform themselves about and observe any such restrictions. Furthermore, by reviewing this presentation, you agree to be bound by the trailing restrictions regarding the information disclosed in these materials. This presentation contains statements that constitute forward-looking statements. These statements include descriptions regarding the intent, belief or current expectations of the Company or its directors and officers with respect to the results of operations and financial condition of the Company. These statements can be recognized by the use of words such as “expects,” “plans,” “will,” “estimates,” “projects,” or other words of similar meaning. Such forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future performance and involve risks and uncertainties, and actual results may differ from those specified in such forward-looking statements as a result of various factors and assumptions. -

Review of Hyderabad Pharmaceutical Industry: an Emerging Global Pharma Hub Jayapala Reddy a V 1,* and B

28362 Jayapala Reddy A V and B. Madhusudhan Rao / Elixir Marketing Mgmt. 76 (2014) 28362-28366 Available online at www.elixirpublishers.com (Elixir International Journal) Marketing Management Elixir Marketing Mgmt. 76 (2014) 28362-28366 Review of Hyderabad pharmaceutical industry: An emerging Global pharma hub Jayapala Reddy A V 1,* and B. Madhusudhan Rao 2 1Department of International Business, School of Management Studies, Vignan University, Vadlamudi PO, Guntur Dist, Andhra Pradesh, India/ General Manager & Head of Asia Business, Mylan Pharma, Hyderabad. 2School of Management Studies, Vignan University, Vadlamudi PO, Guntur Dist, Andhra Pradesh, India. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: India is one of the fastest growing pharmaceutical markets in the world and has established Received: 20 September 2014; itself as a key global hub for research & development, manufacturing of raw materials, Received in revised form: excipients, intermediates, finished dosage formulations, packaging materials, and clinical 27 October 2014; trials for both synthetic and biological drugs. This review paper discusses on how Accepted: 6 November 2014; Hyderabad which was known as a bulk drug capital transformed in to an emerging pharma global pharma hub. Business friendly government policies, visionary entrepreneurs and a Keywords large pool of knowledge base specialized to support industry has transformed Hyderabad a Hyderabad pharma industry, place for many SME’s, Indian & Foreign Multinational Pharma companies. Global pharma hub, Generic drugs © 2014 Elixir All rights reserved. Bulk drugs. Introduction revenues coming from formulations. Majority of the pharma Global Pharmaceutical Industry companies are shifting towards to formulations and hence The Global pharma market is estimated to be around USD 1 accounted for around 71% of total exports in 2013[3]. -

Corporate Action Tracker

Corporate Action Tracker st nd Corporate Action a nd Result Calendar May 21 – Jun 02 , 2018 Bonus Company Ratio Ex-Date G.M.Breweries 1:4 21-May-18 Coastal Corporation 3:1 23-May-18 Split Company Ratio Ex-Date Gaekwar Mills 100:10 31-May-18 Right N.A. Buyback Company Ex Date Start Date End Date Offer Price Smartlink Holdings 17-May-18 -- -- 120.00 Netlink Solutions (India) 18-May-18 -- -- 17.00 Open Offer Company Start Date End Date Offer Price Envair Electrodyne 11-May-18 25-May-18 32.50 Rajputana Investment and Finance 15-May-18 28-May-18 11.50 Econo Trade (India) 16-May-18 29-May-18 20.00 HK Trade International 17-May-18 30-May-18 20.00 Xchanging Solutions 18-May-18 31-May-18 55.22 Dividend for May 21st – Jun 02nd, 2018 Dividend Company Type (In Rs) Ex-Date Merck Dividend 15.00 21-May-18 Mold-Tek Technologies Interim Dividend 0.30 21-May-18 Mold-Tek Packaging Interim Dividend 2.00 21-May-18 Raymond Dividend 3.00 22-May-18 R Systems International Interim Dividend 0.60 22-May-18 Gateway Distriparks Interim Dividend 4.00 23-May-18 GHCL Dividend 5.00 23-May-18 DCB Bank Dividend 0.75 24-May-18 Ingersoll-Rand (India) Interim Dividend 202.00 24-May-18 Trident Final Dividend 0.30 24-May-18 ITC Dividend 5.15 25-May-18 Colgate-Palmolive (India) Interim Dividend -- 29-May-18 Manappuram Finance Interim Dividend 0.50 29-May-18 Suyog Telematics Interim Dividend 1.00 29-May-18 Oberoi Realty Dividend 2.00 31-May-18 Page Industries Interim Dividend -- 31-May-18 Responsive Industries Dividend 0.10 31-May-18 1 Corporate Action Result Calendar for May 21st – Jun 02nd, 2018 Date: 21-May-18 63 moons Technologies AstraZeneca Pharma India CCL Products (India) Colgate Palmolive (India) DLF Dhunseri Petrochem Dhunseri Tea & Industries Future Retail GSPL IL&FS Transportation IMFA Just Dial Mahanagar Gas Motilal Oswal Fin Services Navkar Corporation Petronet LNG Redington (India) Timken India TTK Prestige Date: 22-May-18 Andhra Bank Bata India Bharat Forge Bosch Capital Trust CARE Ratings Cipla Dr.